Andean textiles facts for kids

The Andean textile tradition is super old! It started way before Christopher Columbus arrived in South America and continued into the time when Europeans first settled there. These amazing textiles were mostly found along the western coast of South America, especially in Peru. The dry desert air there helped keep these dyed fabrics safe for thousands of years. Some are even 6,000 years old!

Many of the textiles we still have today were found wrapped around people who had passed away. But these fabrics were used for many things, not just burials. People used woven textiles for special clothes or even as cloth armor. They also used knotted fibers, called quipu, to keep records. Textiles were really important in talking between different groups of people. They were like gifts that leaders would exchange to make peace or show power.

These fabrics also showed how rich someone was, their social status, and where they came from. People in the Andes believed that the materials used for textiles had special spiritual powers. The designs on the textiles also carried important messages about the universe and their beliefs. The thread for these textiles usually came from local cotton plants, or from the wool of alpacas and llamas.

Contents

Ancient Textile Beginnings

Stone Age Discoveries

The very first known textile pieces were found in Guitarrero Cave in Peru. They are super old, dating back to about 8000 BCE! Early fiber work by the Norte Chico people involved twisting and knotting plant fibers. They made things like baskets and containers. Finding finely spun thread and simple cloths shows that people already knew a lot about spinning and weaving a long, long time ago.

Ancient human skeletons from this time were sometimes stuffed with plant fibers and wrapped in rope. This way of preserving bodies was invented in Chile around 5000 BC. This shows that people knew how to spin natural fibers into strong cords very early on.

Early Coastal Life

People living along the coast were the first to make fishing nets. They also used a special openwork style in their knotted items. These fishing nets were made by twining, a method similar to macramé that doesn't use a loom. We've found pieces with knotted patterns that show humans, parrots, snakes, and cats!

First Major Cultures

Around this time, people started raising camelids like alpacas and llamas. These animals were important for their meat, their woolly hair, and for carrying goods. This was especially helpful in the tough mountain environments of the Andes. Alpacas and llamas were highly respected because they provided so many resources. Their woolly fibers were flexible and could soak up dye easily. This made them perfect for weaving with cotton to create strong threads and fabrics.

The Chavín culture started to grow around 900-500 BC. Textiles found from old burials show brown dye painted on large pieces of cloth. Some textiles from Karwa burials were used as special religious objects. They show female gods. The Chavín culture might have been the first to make a lot of textiles for religious and symbolic reasons.

The Paracas culture quickly made textile making a huge and time-consuming job. Beautiful embroidered and woven textiles became very common. They often had repeating patterns that changed slightly. Things like headbands were made using a special looping technique. Paracas leaders wore many layers of clothes, including headbands, turbans, cloaks, ponchos, tunics, skirts, and loincloths.

The Moche people also wove textiles, mostly using wool from vicuña and alpaca. We don't have many examples left, but the people who live in that area today still have strong weaving traditions.

Middle Period Empires

The Middle Horizon period was dominated by the powerful Wari and Tiwanaku cultures in the central Andes.

The ancient city of Wari, which was the capital, is about 11 kilometers (6.8 miles) northeast of modern Ayacucho, Peru. This city was the heart of a civilization that covered much of the mountains and coast of modern Peru.

In 2013, an untouched royal tomb was found at El Castillo de Huarmey. This discovery gave us new clues about how important the Wari were. The many different and rich items found with three royal women show that the Wari culture was very wealthy. They had the power to control a large part of northern coastal Peru for many years.

The Wari are especially famous for their textiles. These fabrics were kept safe in desert burials. The fact that their textile designs were very similar across the empire shows that the Wari government controlled how important art was made. Surviving textiles include tapestries, hats, and tunics for high-ranking officials. Some tunics had miles of thread in them! They often showed very abstract versions of common Andean designs, like the Staff God. It's thought that these abstract designs might have been a secret code to keep out outsiders. The geometric shapes also made the wearer's chest look bigger, showing their high rank.

Wari textiles were large and made in special workshops run by the state. They used chaotic geometric patterns and camelid-like figures to show messages of power and plenty. Examples of these designs show many repeating geometric patterns with bright colors. Experts believe that the complex designs showed how skilled the state was and how many resources it controlled.

Later Cultures and the Inca

Late Intermediate Period

Some of the main cultures during the Late Intermediate Period were Lambayeque, Chimú, and Chancay. The Lambayeque culture started around 750 AD and was strongest between 900 AD and 1100. Lambayeque textiles often mixed styles from older cultures like the Moche and Wari. But they also added their own local symbols, creating a unique style. These older influences included a focus on telling stories. However, Lambayeque's own style included things like sea birds, fish, and crescent-shaped headwear.

The Chancay culture had many different textile styles. These included openwork (like lace), painted designs, and even three-dimensional figures. Chancay textiles often used soft colors, which was different from the Chimú, who used bright, strong colors.

Inca Period: Textiles for Everyone

Inca cloth was super important for both the social life and the economy of their huge empire. After farming, making cloth was the second biggest industry in the Inca Empire. It was also linked to how people were ranked in society.

Rough Cloth – Chusi

The roughest kind of Inca cloth was called chusi. People didn't wear it. Instead, it was used for basic household items like blankets, rugs, and sacks. The threads in this type of cloth could sometimes be as thick as a finger!

Everyday Cloth – Awaska

The next level of Inca weaving was called awaska. This was the most common type of cloth used for Inca clothing. Awaska was made from llama or alpaca wool. It had a much tighter weave (about 120 threads per inch) than chusi cloth.

Thick clothes made from awaska were standard for the common people in the cold Andean highlands. Lighter cotton clothing was made in the warmer coastal areas. The Peruvian Pima cotton used by the Incas is still considered one of the best cottons today.

Royal and Noble Textiles – Qompi

The finest Inca textiles were only for the nobles and the emperor himself. This special cloth, called qompi (or cumbi/kumpi), was incredibly high quality. It needed special workers who were dedicated to making it for the state.

Qompi cloth was made in state-run places called aklla-wasi. Here, chosen women (aklla) wove clothes for the nobles and priests. There were also full-time male weavers, called qompi-kamayok, who made qompi cloth for the state.

Qompi was made from the best materials the Inca could find. Alpaca, especially baby alpaca, and vicuña wool were used to create fancy and richly decorated items. The first Spanish explorers even described Inca textiles made of vicuña fiber as "silk" because they were so smooth.

Amazingly, the finest Inca cloth had more than 600 threads per inch! This was a higher thread count than any European textiles at the time. No one in the world made cloth this fine until the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s!

Inca Fashion Across the Empire

The style of Inca clothing changed depending on where people lived. Heavier, warmer materials like llama, alpaca, and vicuña wool were common in the colder Andean highlands. (Vicuña wool was almost only worn by royalty). Lighter cotton cloth was used in the warmer coastal areas. However, the basic design of Inca clothes was pretty similar everywhere in the Inca Empire. The quality of the materials and the fancy decorations showed how high someone's social rank was.

Women's Clothing

The main piece of Inca clothing for women was a long dress called an anaku. (There were some regional differences in style, like the aksu, which was a longer version of the men's unku). The anaku reached the wearer's ankles and was held around the waist by a wide belt or sash called a chumpi.

A type of shawl or cloak, called a lliclla, was worn over the shoulders. This cloak was fastened with tupu pins made of copper, bronze, silver, or gold. Women also used the cloak to carry things while farming or doing other daily tasks. Just like with other clothes, the materials used for these items depended on the wearer's social rank.

Men's Clothing

A sleeveless shirt or tunic, called an unku (or cushma), was the main item of men's clothing. The unku was usually rectangular. However, some variations existed, like the unku worn by people in the Altiplano (high plains), which was more trapezoidal. Most surviving unku shirts are about 76 cm (30 inches) wide. They reached just above the knee in most Inca areas and had slits for the head and arms.

Unku shirts worn in some warmer coastal areas were much shorter, reaching just above the waist or hip-length. These could be worn with a skirt.

Inca military unku shirts were easy to spot because they had a black and white checkered design.

Many Inca unku shirts have been found on the coasts of Peru and Chile, rather than in the Andes mountains. This is because the dry desert climate of the Atacama desert is much better for preserving textiles.

Underneath the tunic, men wore a breechclout or wara, which was a type of loincloth. It was only worn by men and consisted of two rectangular strips of material that hung down from the waist. Wrapped skirts were also worn in some areas.

An outer garment called a yakkoya (cloak) was worn over the unku. The yacolla was basically a blanket that could be draped over the shoulders. When working or dancing, the yacolla was tied over one shoulder to keep it in place.

Both men and women often carried a woven bag called a chuspa. The bag hung by the wearer's side from a strap around the neck. It held things like coca leaves, personal items, and slingstones.

Men's belts were much narrower than women's waistbands. Unlike women, men didn't have to wear them. However, in some areas, belts were quite popular. But it seems the Inca nobles from Cusco didn't wear them much. A mix of a belt and a bag (chuspa) was very popular among groups in the southern Altiplano.

Headdresses were very different in shape and style. Many kinds of hats, turbans, and headbands were worn. Some even included things like deer antlers, slings, or cords wrapped around the head. These different headdresses showed where people came from in the Inca Empire. For example, the Wanka wore a wide black headband, the Chachapoya wore wool turbans (probably white), and coastal people wore turbans "like those of the gypsies."

Inca Footwear

It was common for many people, especially commoners but also some nobles, to go barefoot a lot of the time. Several types of sandals, shoes similar to Native American moccasins, and high boots (worn in the coldest areas) were worn by both men and women. The soles of Inca sandals could be made from leather or woven plant fibers. The top part of the sandal was made of brightly colored braided wool cord.

Keeping Records with Knots

How Woven Textiles Were Made

Making Techniques

Many textiles, like baskets and fishing nets, didn't need a loom. But for woven textiles, the Andeans used the back strap loom. This is shown in an old book called El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno. They used several techniques to make fabric, including plain weave, tapestry weave, and scroll weave. Smaller woven pieces were often sewn together to make a larger fabric. The edges of embroidered tunics and cloaks were often decorated with yarn tassels or fringe.

Ancient Andean weavers were pioneers in new weaving techniques, like the triple weave and quadruple weave. The use of fine yarn and consistent stitch size is amazing. Studies show an average of 250 threads per inch, and some pieces even have over 500 threads per inch! This is because the threads were very consistent in thickness, and the weavers kept the tension on the loom perfect throughout the whole process.

A mix of cotton and dyed camelid threads made textiles strong and colorful. The scaly hair of camelids (like alpaca and llama) could easily soak up dye. Natural plant-based dyes were set onto the fibers using a natural mordant, like urine. Weavers used complex combinations of colors and patterns to repeat geometric designs while keeping them looking consistent. Paracas textiles are especially known for their neat grid-like arrangement of iconographic images. The consistent size and shape of these patterns suggest that textile artists used counting systems to keep track of stitches and distances between designs.

Workshop Production

Different embroidery methods created unique styles of coloring and images in woven textiles. Block color, linear, and broad line styles of embroidery gave different visual effects. They were used to share different kinds of information. Designs were also painted directly onto woven textiles using various dyes.

Skilled textile artists in cultures before the Inca often worked in large workshops with other artists. Being close to other artists allowed them to add special features to plain woven textiles. These included metallic threads, knotted strings of feathers, and brocading (adding raised patterns). Painting textiles was common for making special cloths for the burial bundles of important people. Pigments like ochre and cinnabar have been used for painting textiles since the Early Horizon period.

Social Importance

Beautifully woven mantles (cloaks) were made for nobles and important people to wear both in life and after death. Mantles were often very large, averaging 275 centimeters (about 9 feet) long and 130 centimeters (about 4 feet) wide. They were draped around the neck and over the shoulders. Women fastened fabrics at the front with a tupu, or shawl pin. The large size of the mantle and the way the images were designed made the wearer look "larger than life." This clearly showed their high status.

Bright dyes helped tell important people apart from those with less status. Commoners wore undyed, brown fabric. Chinchero officers wore red ponchos to show their rank during official government events. Inca rulers wore a llautu, a tasseled red fringe, on their forehead to show their status.

Gifts of textiles were also given to conquered lands. This was a ceremonial way to show dominance over the people of that region. A region's ability to make textiles was closely linked to how successful it was at raising camelids. This showed the value of the wealth controlled by the state in that area.

Burial Bundles

Woven clothes worn during life showed a person's social rank. These clothes were often buried with the person after they died. Special gift textiles made just for burials were also included, even if they hadn't been worn in life. Ritual gift objects wrapped in "mummy bundles" included obsidian knives, combs, and balls of thread.

The Paracas culture practiced mummification by wrapping the deceased in many layers of woven textiles. Over 429 funeral bundles have been found at a burial site called Cerro Colorado. These bundles contained gift textiles, rolls of plain cloth, and various ritual items. These artifacts are the largest source of ancient Andean textile art known today.

Textiles in Battle

Even though Andean civilizations knew how to work with metal, quilted armor made of cloth was preferred. It was lighter and more flexible. Soldiers shown in drawings by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala wear cloth tunics and wrap strips of fabric around themselves. This created strong armor that allowed them to move while still protecting them. Using cloth instead of metal armor also had cultural reasons. People believed that cloth could transfer spiritual strength and power to the wearer, giving them force and might.

For similar reasons, woven slings made of plant fibers were the favorite weapons of the Moche civilization. They preferred these over stiff wooden or metal weapons. Cloth blankets and tent-making equipment were easy to carry. This allowed supplies to be brought to battlefronts. Storage buildings filled with cloth equipment have been found throughout the Tawantin Suyu (the Inca Empire). Armies that were forced to retreat often burned any cloth they couldn't carry. This stopped enemy forces from getting their hands on these valuable supplies.

Colonial Period Changes

When the Spanish conquered the Inca Empire, Spanish settlers moved to the Andean coast. Middle and upper-class Spanish families saw how valuable the finely woven native textiles were. They wanted luxury textiles to decorate their own homes. So, cumbi, a fine tapestry cloth made from alpaca fibers, was changed to match Spanish colors. It was then made for the homes and churches of the settlers. The term tornasol refers to a textile style that Andean weavers learned from Europeans. It had a silky texture that seemed to change color when viewed from different angles.

Native weavers changed their techniques to make common items for their new colonial customers. Bedcovers, table covers, rugs, and wall hangings became popular textile items in the late 1700s. European influences brought lace-inspired borders and fancy circular patterns.

Traditionally, garments had been brightly colored and highly patterned. But the clothes worn by highland Andeans during the Colonial period were usually plain and black. Some people think this was a way to mourn the lost Inca empire. But it might also have been because of cultural influences brought by the Spanish colonists.

In the 1500s, Spanish leaders started to see Andean textiles as something they could sell. Historian Karen Graubart explains that Spanish leaders made Indigenous women weave clothing. This clothing was then sold by their local chiefs (caciques). This division of weaving by gender happened during the colonial period because Spanish leaders thought Indigenous men would be busy with their forced labor (mitas).

The main buyers of this clothing were mitayos, who were Indigenous laborers mostly working in mines, and Indigenous people living in cities. Employers of Indigenous servants and laborers also bought this clothing. Many of them promised outfits in their labor contracts.

Gallery

-

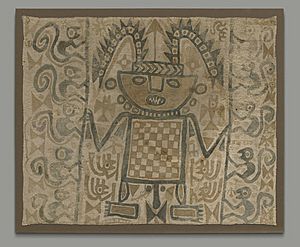

Nazca-Paracas mantle, 1-100 CE, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn. -

Paracas textile, 100-300 C.E., Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn.

-

Paracas mantle, c. 200 C.E., Larco Museum, Lima. -

Wari textile fragment, 650-900 C.E., Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

-

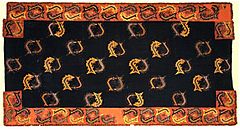

Wari tunic, 750-950 C.E., Textile Museum, Washington, D.C. -

Border fragment, 900-1400 C.E., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

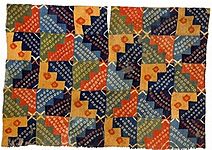

Tupa Inca tunic, c. 1550 C.E., Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

Painted textile fragment, 1000-1476 C.E., Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

-

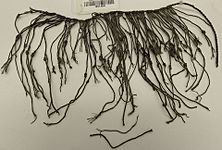

Cotton quipu, 1400-1600 C.E., Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

-

Chimu shirt, 1450-1550 C.E., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |