Aylesbury duck facts for kids

The Aylesbury duck is a special type of domesticated duck. It was first bred mainly for its meat and its beautiful white look. This duck is quite large with pure white feathers, a pink beak, and orange legs and feet. It has a unique shape, with its body staying flat, parallel to the ground. We don't know exactly when or how this breed started. However, raising white ducks became popular in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, England, in the 1700s. People wanted their white feathers to fill quilts. Over the 1800s, people carefully bred these ducks to make them bigger, better shaped, and whiter. This is how the Aylesbury duck breed came to be.

Raising ducks became a huge business in Aylesbury during the 1800s. Ducks were bred on farms in the countryside nearby. Then, fertilised eggs were brought into a part of the town called "Duck End." Here, local people would raise the ducklings in their homes. When a railway line opened to Aylesbury in 1839, it became easy and cheap to send ducks quickly to markets in London. This made duck raising very profitable. By the 1860s, the duck business started to move out of Aylesbury to other towns and villages. The industry in Aylesbury itself began to shrink.

In 1873, the Pekin duck was brought to the United Kingdom. Even though many thought its meat didn't taste as good as the Aylesbury duck's, the Pekin was tougher and cheaper to raise. Many farmers switched to Pekin ducks or bred Aylesbury-Pekin mixes. By the early 1900s, the Aylesbury duck industry was struggling. This was due to competition from Pekin ducks, too much inbreeding, diseases in the pure Aylesbury ducks, and the rising cost of duck food.

The First World War severely harmed the duck industry in Buckinghamshire. It wiped out small farms, leaving only a few large ones. The Second World War caused even more problems. By the 1950s, only one important group of Aylesbury ducks was left in Buckinghamshire. By 1966, there were no duck-breeding or -raising businesses left in Aylesbury itself. Today, there is only one surviving group of pure Aylesbury ducks in the UK. The breed is also critically endangered in the United States. Still, the Aylesbury duck remains a symbol of the town of Aylesbury. You can see it on the town's coat of arms and on the club badge of Aylesbury United.

Contents

What is an Aylesbury Duck?

The exact start of the Aylesbury duck is not fully clear. Before the 1700s, duck breeds were rarely written down in England. The common farm duck was a tamed version of the wild mallard. These common ducks came in different colours, and sometimes white ones would appear naturally. White ducks were very valuable because their feathers were popular for filling quilts.

In the 1700s, people started carefully breeding white common ducks. This led to a white domestic duck, often called the English White. Ducks had been farmed in Aylesbury since at least the 1690s. Raising English Whites became popular in Aylesbury and nearby villages. By 1813, it was noted that "ducks are an important item at market from Aylesbury." They were white and seemed to grow quickly. Poor people bred and raised them, then sent them to London every week. Aylesbury duck farmers worked hard to keep the ducks pure white. They kept them away from dirty water, soil with lots of iron, and bright sunlight. All these things could make the feathers change colour. Over time, carefully breeding the English White for its size and colour slowly led to the Aylesbury duck we know today.

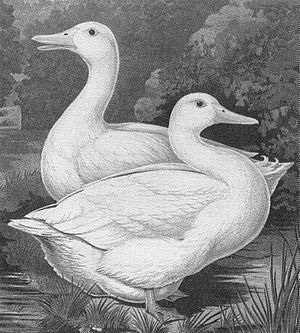

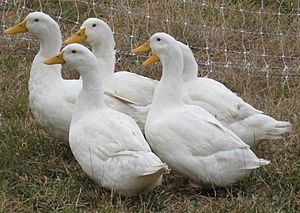

The Aylesbury duck is a rather large breed. It has pure white feathers and bright orange legs and feet. Its legs are in the middle of its body, and it stands with its belly flat to the ground. This gives it a "boat-shaped" body. It has a fairly long, thin neck, like a swan, and a long, pink beak that comes straight out from its head.

An Aylesbury duckling stays in its egg for 28 days. For the first eight weeks after hatching, ducks (females) and drakes (males) look almost the same. This is until their first moult (when they shed feathers). After moulting, males have two or three curved tail feathers. Their quack is also fainter and huskier than the female's. By one year old, females usually weigh about 6 pounds, and males about 7 pounds. Some males can even reach around 10 pounds.

Unlike the Rouen duck, another popular meat duck in England in the 1800s, Aylesbury ducks lay eggs starting in early November. Aylesbury ducks get fat quickly. By eight weeks old, they weigh up to 5 pounds. This is big enough to eat, but they are still young and very tender. Because of this, their meat was available from February onwards. This was after the hunting season for game ended, but before the first spring chickens were ready. Rouen ducks, which looked more like mallards and were less valuable, laid eggs from early February. They took six months to grow big enough to eat. So, Aylesbury ducks were mostly sold in spring and summer, and Rouen ducks in autumn and winter.

How Aylesbury Ducks Were Farmed

In England at this time, most animal farming was done by one group. But for Aylesbury ducks, there were two separate groups: the duck breeders and the duck rearers. Stock ducks, which were ducks kept for breeding, stayed on farms in the countryside of the Aylesbury Vale. This was away from the town's polluted air and water. This kept the ducks healthy and meant more fertile eggs.

Breeders would choose stock ducks from ducklings hatched in March. A typical breeder would keep six males and twenty egg-laying females at a time. The females would be kept for about a year before mating, usually with an older male. Then, they were often replaced to avoid problems from inbreeding. Stock ducks could roam freely during the day. They would swim in local ponds. These ponds were privately owned but treated as common property by duck breeders. Breeders would mark their ducks on the neck or head. The stock ducks would search for plants and insects. They also ate greaves (leftover bits after animal fat is processed). Since ducks lay their eggs at night, they were brought indoors overnight.

Female Aylesbury ducks would not sit still for the 28 days needed for their eggs to hatch. Because of this, breeders would not let mothers sit on their own eggs. Instead, the fertilised eggs were collected and given to the "duckers" in Aylesbury's Duck End.

Raising the Ducklings

The duckers in Aylesbury would buy eggs from the breeders. Or, a breeder would pay them to raise the ducks. They raised the ducklings in their homes from November to August as a way to earn extra money. Duckers were usually skilled workers who used their extra income to buy ducklings. Many of the tasks for raising ducks were done by the women of the house, especially caring for new ducklings.

The eggs were divided into groups of 13. Each group was placed under broody chickens. In the last week of the four-week hatching time, the eggs were sprinkled daily with warm water. This softened the shells, helping the ducklings hatch.

New Aylesbury ducklings are shy. They do best in small groups. So, duckers would divide them into groups of three or four ducklings, each with a hen. As the ducklings grew older and braver, they were kept in groups of about 30. At first, ducks were kept in every room of the ducker's cottage. But by the late 1800s, they were kept in outdoor pens and sheds with good protection from cold weather.

The ducker's goal was to make every duckling as fat as possible by eight weeks old. This was the age of their first moult, when they would be killed for meat. They also avoided foods that would make their bones too big or their meat greasy. In their first week, ducklings ate boiled eggs, toast soaked in water, boiled rice, and beef liver. From the second week, this diet slowly changed to barley meal and boiled rice mixed with greaves. (Some bigger duckers would boil a horse or sheep and feed this to the ducklings instead of greaves.) This high-protein diet was also given with nettles, cabbage, and lettuce for vitamins. Like all birds, ducks need grit in their diet to help digest food. Aylesbury ducklings' drinking water had grit from Long Marston and Gubblecote. This grit also gave their beaks their special pink colour. About 85% of ducklings survived this eight-week raising process and were sent to market.

Ducks naturally like water, but swimming can be risky for young ducklings. It can also stop them from growing. So, even though duckers always made sure ducklings had a trough or sink to splash in, the ducklings were kept away from larger bodies of water while they grew. The only exception was just before they were killed. Then, the ducklings would be taken for one swim in a pond. This helped their feathers grow properly.

While a few large duck farms in Aylesbury raised thousands of ducklings each season, most Aylesbury duckers raised between 400 and 1,000 ducklings each year. Duck raising was a side job, so it wasn't listed in Aylesbury's records. We can't know how many people were doing it. Kelly's Directory for 1864 doesn't list any duck farmers in Aylesbury. But an 1885 book says that "in the early 1800s, almost every householder at the 'Duck End' of the town raised ducks." It was common to see young ducks of different ages in pens, taking up most of the living room. New ducklings were even kept in the bedroom.

The Duck End was one of the poorer areas of Aylesbury. Until the late 1800s, it had no sewers or rubbish collection. The area had many open ditches filled with dirty water. Outbreaks of malaria and cholera were common. The cottages had poor air flow and light, and no running water. Duck waste from the ponds soaked into the soil and leaked into the cottages through cracks in the floors.

Selling the Ducks

When the ducklings were ready, duckers usually killed them at their own homes. This was generally done in the morning so the ducks would be ready for market in the evening. To keep the meat as white as possible, the ducks were hung upside down. Their necks were broken backwards, and they were held there until their blood flowed to their heads. They stayed in this position for ten minutes before being plucked. If not, blood would gather in the plucked areas. The plucking was usually done by the women of the house. The plucked ducks were sent to market, and the feathers were sold directly to London dealers.

The market for duck meat in Aylesbury itself was small. So, the ducks were usually sent to London for sale. By the 1750s, Richard Pococke noted that four cartloads of ducks were sent from Aylesbury to London every Saturday. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, ducks continued to be sent over the Chiltern Hills to London by packhorse or cart.

On June 15, 1839, Sir Harry Verney, 2nd Baronet, opened the Aylesbury Railway. This line was built by Robert Stephenson. It connected the London and Birmingham Railway's Cheddington railway station to Aylesbury High Street railway station. On October 1, 1863, the Wycombe Railway also built a line to Aylesbury. It went from Princes Risborough railway station to a station on the west side of Aylesbury (today's Aylesbury railway station). The railway greatly changed the duck industry. By 1850, up to a ton of ducks were being shipped from Aylesbury to Smithfield Market in London each night.

A system was set up where salesmen gave labels to the duckers. The duckers would put these labels on their ducklings, showing which London firm they wanted them sold to. The railway companies would collect the ducklings, take them to the stations, ship them to London, and deliver them to the right firms. They charged a set fee per bird. This system helped everyone. Duckers didn't have to travel to market, and London salesmen didn't have to collect the ducklings. Duck raising became very profitable. By 1870, the duck industry brought over £20,000 per year into Aylesbury. A typical ducker could make a profit of about £80–£200 per year.

Changes in the Late 1800s

In 1845, the first National Poultry Show was held at the Zoological Gardens in London. One of the bird types shown was "Aylesbury or other white variety." Queen Victoria's personal interest in poultry farming and its display at the Great Exhibition of 1851 made the public even more interested in poultry. From 1853, the Royal Agricultural Society and the Bath and West of England Society, England's two main agricultural groups, added poultry sections to their yearly shows. This led to smaller local poultry shows starting up across the country.

Breeders would pick ducks for shows from newly hatched ducklings in March and April. These ducks got a lot of extra care. They were fed a special diet to make them as heavy as possible. They were also let out for a few hours each day to keep them in good shape. Before the show, their legs and feet were washed. Their beaks were trimmed with a knife and smoothed with sandpaper. Their feathers were brushed with linseed oil. Most breeders gave the ducks a healthy meal before the show to calm them. But some breeders would force-feed the ducks with sausage or worms to make them as heavy as possible. Show judges looked mainly at an Aylesbury duck's size, shape, and colour. This encouraged breeding larger ducks with very noticeable keels (a deep chest) and loose, baggy skin. By the early 1900s, the Aylesbury duck had split into two types: one bred for looks and one for meat.

The Rise of Pekin Ducks

In 1873, the Pekin duck was brought from China to Britain for the first time. It looked similar to an Aylesbury duck. A Pekin is white with orange legs and beak. Its legs are near the back, making it stand upright on land. While its meat wasn't thought to be as tasty as the Aylesbury's, the Pekin was tougher. It laid more eggs, got fat faster, and was about the same size as an Aylesbury at nine weeks old.

Meanwhile, Aylesbury ducks were becoming too inbred. This meant fewer fertile eggs and the ducks were more likely to get sick. Show standards had led breeders to choose ducks with an exaggerated keel, even though buyers didn't like it. Poultry show judges also liked the long neck and upright stance of Pekin ducks more than the boat-like stance of the Aylesbury. Some breeders in the Aylesbury area started mixing Pekin ducks with the pure Aylesbury type. These Aylesbury-Pekin cross ducks didn't have the delicate taste of the pure Aylesbury, but they were tougher and much cheaper to raise.

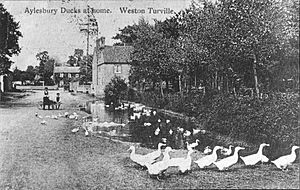

Until the mid-1800s, duck raising was mostly in the Duck End. But by the 1860s, it had spread to many other towns and villages nearby, especially Weston Turville and Haddenham. Years of duck raising had polluted Aylesbury's soil. New public health laws also stopped many old practices. This caused the duck raising industry in the Duck End to decline. By the 1890s, most Aylesbury ducks were raised in villages, not in the town itself. Changes in population and a better national rail network meant ducks didn't need to be raised so close to London. Large duck farms opened in Lancashire, Norfolk, and Lincolnshire. Even though the number of ducks raised across the country kept growing, the number of ducks raised in the Aylesbury area stayed the same between 1890 and 1900. From 1900, it started to drop.

Why the Aylesbury Duck Declined

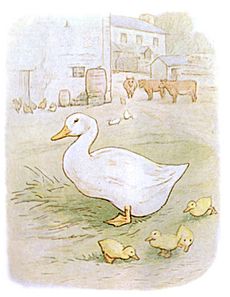

By the time Beatrix Potter's 1908 story The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck brought new interest to the breed, the Aylesbury duck was already in serious decline. (Jemima Puddle-Duck was an Aylesbury duck, even though the story was set in Cumbria.) The duck farmers of Buckinghamshire generally didn't adopt new technologies like the incubator. Also, too much inbreeding had made the breed dangerously weak. At the same time, the cost of duck food had gone up four times over the 1800s. From 1873 onwards, competition from Pekin and Pekin cross ducks was making Aylesbury ducks less popular in the market.

The First World War badly hurt the remaining duck farmers in Buckinghamshire. The price of duck food went up sharply, while people wanted fewer expensive foods. Wartime changes also ended the helpful financial deals with the railway companies. By the end of the war, small-scale duck raising in the Aylesbury Vale had disappeared. Duck raising was now mostly done by a few large farms. Shortages of duck food during the Second World War caused even more problems for the industry. Almost all duck farming in the Aylesbury Vale stopped. A 1950 "Aylesbury Duckling Day" campaign tried to improve the Aylesbury duck's reputation but had little effect. By the late 1950s, the last important farms had closed. Only one group of ducks remained in Chesham, owned by Mr. L. T. Waller. By 1966, there were no duck breeders or rearers of any size left in Aylesbury. As of 2015, the Waller family's farm in Chesham is still in business. It is the last remaining group of pure Aylesbury meat ducks in the country.

Aylesbury ducks were brought to the United States in 1840. However, they never became a very popular breed there. They were added to the American Poultry Association's Standard of Perfection breeding rules in 1876. As of 2013, the breed was listed as critically endangered in the United States by The Livestock Conservancy.

Aylesbury Duck's Legacy Today

The Aylesbury duck is still an important symbol of the town of Aylesbury. Aylesbury United F.C. (a football club) is nicknamed "The Ducks." Their club badge even has an Aylesbury duck on it. The town's coat of arms also includes an Aylesbury duck and plaited straw. These represent the town's two main historic industries. The Aylesbury Brewery Company, which no longer exists, used the Aylesbury duck as its logo. You can still see an example of this at the Britannia pub. Duck Farm Court is a shopping area in modern Aylesbury. It is near the old area of California, which was one of the main places for breeding ducks in the town. There have also been two pubs in the town called "The Duck" in recent years. One in Bedgrove has been torn down, and one in Jackson Road has recently changed its name.