Battle of Arawe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Arawe |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II's Pacific War | |||||||

U.S. Army soldiers land at Arawe |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,750 | 1,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 118 killed 352 wounded 4 missing |

304 killed 3 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Arawe (also called Operation Director) was a fight during World War II. It took place between Allied and Japanese forces. This battle was part of the larger New Britain campaign.

The main goal of the Arawe battle was to distract Japanese forces. This would make it easier for a bigger Allied landing at Cape Gloucester later in December 1943. The Japanese were already expecting an attack in western New Britain. They were sending more troops to the area when the Allies landed at Arawe on December 15, 1943.

The Allies took control of Arawe after about a month of fighting. The Japanese force was much smaller. Some historians still debate if the Arawe attack was truly needed. Some say it helped distract the Japanese. Others think the whole campaign in western New Britain was not necessary. They believe the troops used at Arawe could have been better used elsewhere.

Contents

Why the Battle of Arawe Happened

The Big Picture: World War II in the Pacific

In July 1942, the U.S. military leaders decided on a big goal. Allied forces in the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific would capture Rabaul. This was a major Japanese base on the eastern tip of New Britain.

From August 1942, U.S. and Australian forces began attacking. They moved through New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Their aim was to remove Japanese forces and build air bases near Rabaul. The Japanese fought hard but could not stop the Allies.

In June 1943, the Allies started a huge plan called Operation Cartwheel. This plan was to capture Rabaul. Over the next five months, Australian and U.S. forces, led by General Douglas MacArthur, moved along New Guinea's north coast. They captured Lae and the Huon Peninsula. At the same time, U.S. forces under Admiral William Halsey, Jr. advanced through the Solomon Islands. They set up an air base at Bougainville in November 1943.

By June 1943, U.S. leaders decided they didn't need to capture Rabaul directly. They thought they could stop the Japanese base by blockade and air bombardment. General MacArthur first disagreed. But this new plan was approved in August 1943.

The Japanese military leaders looked at the war situation in September 1943. They thought the Allies would try to break through the Solomon Islands and Bismarck Archipelago. This would lead them closer to Japan. So, Japan sent more troops to important places to slow the Allies down. They kept many strong forces at Rabaul. They believed the Allies would still try to capture that town.

At that time, Japanese positions in western New Britain were few. They had airfields at Cape Gloucester and small stops. These stops helped small boats traveling between Rabaul and New Guinea hide from Allied air attacks.

Planning the Attack on Western New Britain

On September 22, 1943, General MacArthur's headquarters gave orders. Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Alamo Force was to secure western New Britain. This operation, called Operation Dexterity, had two main goals.

- First, to build air and PT boat bases. These would be used to attack Japanese forces at Rabaul.

- Second, to control the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits. These straits were between New Guinea and New Britain. Controlling them would allow Allied ships to pass safely. This was important for future landings along New Guinea's coast.

To achieve this, both Cape Gloucester and Gasmata on New Britain's south coast were to be captured. The 1st Marine Division was chosen for the Cape Gloucester operation. A strong group from the 32nd Infantry Division was to attack Gasmata.

However, Allied commanders disagreed about landing in western New Britain. Lieutenant General George Kenney, who led Allied Air Forces, thought it was unnecessary. He said existing air bases were enough to support future landings. Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender and Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey agreed about Cape Gloucester. They wanted to secure both sides of the straits. But they opposed the Gasmata landing. It was too close to Japanese air bases at Rabaul. Because of these concerns and new information about Japanese troops, the Gasmata operation was canceled in early November.

On November 21, a meeting was held in Brisbane. It was decided to land a small force in the Arawe area instead. This operation had three goals:

- To distract Japanese attention from Cape Gloucester.

- To provide a base for PT boats.

- To set up a defense area and connect with the Marines when they landed.

PT boats from Arawe would stop Japanese barges along New Britain's southern shore. They would also protect Allied naval forces at Cape Gloucester.

The Land: Arawe's Geography

The Arawe area is on the south coast of New Britain. It is about 100 mi (160 km) from the island's western tip. The main feature is Cape Merkus, which forms the "L"-shaped Arawe Peninsula. Small islands, called the Arawe Islands, are southwest of the cape.

In late 1943, the Arawe Peninsula was covered in coconut trees. The land inland and on the islands was swampy. Most of the shoreline had limestone cliffs. There was a small, unused airfield 4 mi (6.4 km) east of the Arawe Peninsula. A coastal path led east from Cape Merkus to the Pulie River. From there, paths went inland and along the coast.

West of the peninsula was a difficult area of swamp and jungle. It was very hard for troops to move through. Several beaches in the Arawe area were good for landing boats. The best were House Fireman Beach, on the peninsula's west coast, and one near Umtingalu village, east of the peninsula's base.

Getting Ready for Battle

Planning the Attack

The Alamo Force was in charge of planning the invasion. The Arawe landing was set for December 15. This was the earliest date that air bases in New Guinea could be ready to support the landing. This also gave the landing force time to train.

Arawe was thought to be lightly defended. So, a smaller force was used than planned for Gasmata. This force, called the Director Task Force, gathered at Goodenough Island. They removed any equipment not needed for fighting. They planned to carry enough supplies for 30 days and ammunition for three days of intense combat. After landing, they would increase supplies to 60 days and ammunition to six days. Anti-aircraft ammunition would be for 10 days. The attack force and its supplies would travel on fast ships for quick unloading.

Commander Morton C. Mumma, who led the PT boat force, did not want to build a large PT boat base at Arawe. He had enough bases, and Japanese barges usually sailed along New Britain's north coast. He convinced Admirals Arthur S. Carpender and Daniel E. Barbey that a full base was not needed. Instead, six PT boats from New Guinea and Kiriwina Island would patrol New Britain's south coast each night. Only emergency refueling would be needed at Arawe.

Brigadier General Julian Cunningham, the Director Task Force commander, gave his orders on December 4. The Task Force would first capture the Arawe Peninsula and nearby islands. They would also set up an outpost on the path to the Pulie River. The main force would land at House Fireman Beach at dawn.

Two smaller groups would land about an hour before the main landing. One group would capture Pitoe Island to the south. It was believed the Japanese had a radio station and defense there. The other group would land at Umtingalu. They would block the coastal path east of the peninsula. Once the beach was secure, patrols would go west of the peninsula. They would try to meet the 1st Marine Division at Cape Gloucester. Navy planners worried about these smaller landings. A night landing at Lae in September had been difficult.

Who Was Fighting: The Forces Involved

The Director Task Force was built around the U.S. Army's 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team (112th RCT). This regiment had arrived in the Pacific in August 1942 but had not fought yet. It became an infantry unit in May 1943. It made an unopposed landing at Woodlark Island on June 23.

The 112th Cavalry Regiment was smaller than regular U.S. infantry regiments. It had only two battalion-sized squadrons, not three. Its squadrons were also smaller and had lighter equipment. The 112th RCT's support units included the 148th Field Artillery Battalion and the 59th Engineer Company. Other units included anti-aircraft artillery, a Marine Corps amphibious tractor company, and a dog platoon. The 2nd Battalion of the 158th Infantry Regiment was kept in reserve. Several other support units would arrive after the landing. Cunningham asked for 90 mm (3.54 in) anti-aircraft guns, but none were available.

The Director Task Force was supported by Allied naval and air units. The naval force included several destroyers, minesweepers, and landing ships. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) would support the landing. However, limited air support would be available after December 15. This was because planes were needed for other important missions.

Australian coastwatchers on New Britain helped a lot. They were reinforced in September and October 1943. They warned of air attacks from Rabaul and reported Japanese movements. One team was already at Cape Orford. Five more teams were sent to other key locations. One team was caught by the Japanese, but the others were in place by late October.

At the time of the Allied landing, Arawe had only a small Japanese force. However, more troops were on their way. The Japanese force at Arawe had 120 soldiers and sailors. They were from the 51st Division. Reinforcements were from the 17th Division. These troops had been sent from China to Rabaul in October 1943. They were meant to strengthen western New Britain.

The ships carrying these troops were attacked by U.S. submarines and bombers. They lost 1,173 soldiers. The 1st Battalion, 81st Infantry Regiment, was supposed to defend Cape Merkus. But it didn't leave Rabaul until December. It had lost many men when its ship was sunk. Also, two of its rifle companies and most of its heavy machine guns were kept at Rabaul. This left the battalion with only its headquarters, two rifle companies, and a machine gun platoon. This battalion, led by Major Masamitsu Komori, was a four-day march from Arawe when the Allies landed.

A company of soldiers from the 54th Infantry Regiment and some engineers were also assigned to Arawe. All Japanese ground forces at Arawe were under General Matsuda, whose headquarters were near Cape Gloucester. Japanese air units at Rabaul were much weaker. They had been attacked by Allies and some planes were moved. Still, the Imperial Japanese Navy's (IJN) 11th Air Fleet had 100 fighters and 50 bombers at Rabaul.

Before the Main Attack

The Allies didn't know much about western New Britain's land or Japanese forces. So, they took many air photos. Small ground patrols also landed from PT boats. A team from Special Service Unit No. 1 checked Arawe on the night of December 9/10. They found few Japanese troops. The Japanese saw this group near Umtingalu village and made their defenses stronger there.

Operation Dexterity started with a big Allied air attack. This aimed to weaken Japanese air units at Rabaul. From October 12 to early November, the Fifth Air Force often attacked airfields and ships in Rabaul harbor. Aircraft from U.S. Navy carriers also attacked Rabaul on November 5 and 11. This supported the Marines' landing at Bougainville.

Allied air forces began pre-invasion raids on western New Britain on November 13. Few attacks were made on Arawe itself. The Allies wanted to surprise the Japanese. Instead, heavy attacks hit Gasmata, Ring Ring Plantation, and Lindenhafen Plantation on New Britain's south coast. Arawe was first hit on December 6 and again on December 8. There was little resistance. On December 14, the day before the landing, heavy air attacks on Arawe began. Allied planes flew 273 missions against targets on New Britain's south coast that day. Also, two Australian and two American destroyers bombed the Gasmata area on the night of November 29/30.

The Director Task Force gathered at Goodenough Island in early December 1943. The 112th Cavalry was told about the Arawe operation on November 24. They sailed to Goodenough Island in two groups on November 30 and December 1. All parts of the regiment were ashore by December 2. A full practice landing was held on December 8. This showed problems with coordinating the waves of boats. It also showed some officers needed more training in amphibious warfare. There wasn't enough time for more training.

At Goodenough, the 112th Cavalry soldiers received new infantry weapons. They had not used these before. Each rifle squad got a Browning Automatic rifle and a Thompson submachine gun. Also, bazookas, rifle grenades, and flame throwers were given out. The cavalrymen had little training on these weapons. They didn't know how to use them best in battle.

The invasion force boarded transport ships on the afternoon of December 13. The convoy sailed at midnight. It went to Buna to meet most of the escorting destroyers. It then pretended to go north toward Finschhafen. After dark on December 14, it turned toward Arawe. A Japanese aircraft spotted the convoy shortly before it anchored off Arawe at 03:30 on December 15. The 11th Air Fleet at Rabaul began preparing planes to attack it.

The Battle Begins

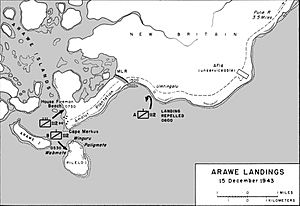

The Landings

Soon after the ships arrived off Arawe, Carter Hall launched LVT amphibious tractors. Westralia lowered landing craft. Both were operated by special Marine and U.S. Army units. The two large transport ships left for New Guinea at 05:00. The fast transport ships carrying "A" and "B" Troops of the 112th Cavalry Regiment's 1st Squadron moved close. They were about 1,000 yd (910 m) from Umtingalu and Pilelo Island. The soldiers then got into rubber boats.

"A" Troop's attempt to land at Umtingalu failed. Around 05:25, the troop came under fire as it neared the shore. Machine guns, rifles, and a 25 mm (0.98 in) cannon fired at them. All but three of their 15 rubber boats were sunk. The destroyer Shaw, meant to support the landing, could not fire until 05:42. Her crew couldn't tell if the soldiers in the water were in the way. Once clear, Shaw silenced the Japanese with two shots from her 5 in (130 mm) guns. The surviving cavalrymen were saved by small boats. They later landed at House Fireman beach. This operation resulted in 12 killed, four missing, and 17 wounded.

"B" Troop's landing at Pilelo Island was successful. The goal was to destroy a Japanese radio station. It was thought to be at Paligmete village on the island's east coast. The landing site was changed to the island's west coast after "A" Troop was attacked. After leaving their boats, the cavalrymen moved east. They came under fire from a small Japanese force in two caves. These were near Winguru village on the island's north coast. Ten cavalrymen stayed to contain the Japanese. The rest of the troop continued to Paligmete. The village was empty and had no radio station. Most of "B" Troop then attacked Winguru. They used bazookas and flamethrowers to destroy the Japanese positions. One American and seven Japanese soldiers were killed. RAAF No. 335 Radar Station personnel also landed on Pilelo Island. They set up a radar station within 48 hours.

The 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry Regiment, made the main landing at House Fireman Beach. A strong current and problems forming the landing vehicles delayed it. The first wave landed at 07:28, not 06:30. Destroyers bombed the beach with 1,800 rounds of 5-inch ammunition. This was between 06:10 and 06:25. B-25 Mitchell planes then fired at the area. But the landing area was not under fire as troops approached. This allowed Japanese machine gunners to fire at the LVTs. But these guns were quickly silenced by rockets from SC-742 and two DUKWs.

The first wave of cavalrymen met little resistance. There were more delays in landing the next waves. This was due to different speeds of the LVTs. The next four waves were supposed to land every five minutes. But the second wave landed 25 minutes after the first. The next three waves landed all at once 15 minutes later. Within two hours, all large Allied ships, except Barbey's flagship, had left Arawe. Conyngham stayed to rescue survivors from Umtingalu. She left later that day.

Once ashore, the cavalrymen quickly secured the Arawe Peninsula. An American patrol found only scattered resistance. More than 20 Japanese in a cave were killed. The remaining Japanese units retreated east. The 2nd Squadron reached the peninsula's base by 14:30. They began preparing their main line of resistance (MLR). By the end of December 15, over 1,600 Allied troops were ashore. The two Japanese Army companies at Arawe retreated northeast. They took positions at Didmop, about 8 mi (13 km) from the MLR. The naval unit defending Umtingalu retreated inland in confusion.

The Allied naval force off Arawe was heavily attacked by air. At 09:00, eight Aichi D3A "Val" dive bombers and 56 A6M5 "Zero" fighters attacked. They avoided the USAAF combat air patrol of 16 P-38 Lightnings. The Japanese attacked the first supply ships. These included five Landing Craft Tank and 14 Landing Craft Medium. But these ships avoided the bombs. The first wave of attackers had no losses. But at 11:15, four P-38s shot down a Zero. At 18:00, 30 Zeros and 12 "Betty" and "Sally" bombers were driven off by four P-38s. The Japanese lost two Zeros that day, but both pilots survived.

Air Attacks and Building the Base

U.S. ground troops faced no opposition right after the landing. But ships carrying reinforcements to Arawe were attacked repeatedly. The second supply group was attacked continuously on December 16. This led to the loss of APc-21. SC-743, YMS-50, and four LCTs were also damaged. About 42 men on these ships were killed or seriously wounded. Another group of ships was attacked three times on December 21 while unloading at Arawe. Overall, at least 150 Japanese planes attacked Arawe that day. More air attacks happened on December 26, 27, and 31.

However, Allied air forces successfully defended Arawe. The coastwatcher teams in New Britain gave 30 to 60 minutes warning of most incoming raids. Between December 15 and 31, at least 24 Japanese bombers and 32 fighters were shot down near Arawe. During the same time, Allied air units also raided airfields at Rabaul and Madang in New Guinea. These were believed to be the bases for the planes attacking Arawe. In air fights over Rabaul on December 17, 19, and 23, 14 Zeros were shot down. Unloading ships at Arawe was difficult due to air attacks and crowding on House Fireman Beach. The beach party was new and too small, causing delays. Some LCTs left before unloading all their cargo.

Air attacks on Arawe decreased after January 1, 1944. The Japanese suffered heavy losses. Also, Allied raids damaged Rabaul. So, Japanese air units only made small night raids after this date. IJN fighter units at Rabaul and Kavieng were busy defending their bases from constant Allied air attacks. Few raids were made against Arawe after 90 mm (3.54 in) anti-aircraft guns were set up there on February 1. These weak attacks did not stop Allied ships. In the three weeks after the landing, 6,287 short tons (5,703 t) of supplies and 541 artillery guns and vehicles were brought to Arawe. On February 20, Japanese air units at Rabaul and Kavieng were moved to Truk. This ended any major air threat to Allied forces in New Britain from the IJN.

After the landing, the 59th Engineer Company built support facilities in Arawe. Because of Japanese air raids, building a partially underground hospital was a priority. It was finished in January 1944. This was replaced by a 120-bed above-ground hospital in April 1944. Pilelo Island was chosen for PT boat facilities. A pier for refueling and fuel storage bays were built there. A 172 ft (52 m) pier was built at House Fireman Beach. This was between February 26 and April 22, 1944, for small ships. Three LCT jetties were also built north of the beach.

A 920 ft (280 m) by 100 ft (30 m) airstrip was quickly built for artillery observation planes on January 13. This was later improved and surfaced with coral. The engineer company also built 5 mi (8.0 km) of all-weather roads in the Arawe region. They provided water using salt water distillation units on Pilelo Island and wells on the mainland. These projects were often delayed by lack of building materials. But the engineers finished them by being creative and using salvaged materials.

The 112th Cavalry RCT strengthened its defenses in the week after the invasion. "A" Troop had lost all its weapons and equipment during the Umtingalu landing attempt. So, supplies were air-dropped to re-equip the unit on the afternoon of December 16. The troop also received 50 replacement soldiers. Most of "B" Troop was also moved from Pilelo Island to the mainland. The regiment improved its MLR by clearing plants to create clear fields of fire. They also set up minefields, wire fences, and a field telephone network. A backup defense line was also built closer to Cape Merkus. Patrols were done daily along the peninsula's shores. They searched for Japanese trying to sneak into the Task Force's rear area. These patrols found and killed between ten and twenty Japanese near Cape Merkus.

The regiment also set up observation posts throughout the Arawe area. These included positions in villages, key spots on the peninsula, and on several offshore islands. "G" Troop was assigned to secure Umtingalu. After doing so, the troop set up a patrol base there. They also had two observation posts along the path connecting it to the MLR.

American Counter-Attack

An American patrol found the Japanese defense position on January 1, 1944. "B" Troop of the 112th Cavalry Regiment attacked later that morning. But they were pushed back by heavy fire. The Americans had three killed and 15 wounded. On January 4, "G" Troop had three killed and 21 wounded in an unsuccessful attack. This attack was on strong Japanese positions. It was done without artillery support to try and surprise the Japanese. It also included a fake attack on Umtingalu with several LCMs. More attacks on January 6, 7, and 11 failed to advance. But they gave the cavalrymen experience in moving through Japanese defenses. These American operations were small. Cunningham and other senior officers believed the landing's goals were already met. They did not want more unnecessary casualties.

On January 6, Cunningham asked for more help, including tanks. Krueger approved this request. He ordered "F" Company, 158th Infantry Regiment, and "B" Company of the USMC 1st Tank Battalion to Arawe. The two units arrived on January 10 and 12. The Marine tanks and two companies of the 158th Infantry then practiced working together. This was from January 13 to 15. During this time, the 112th Cavalry continued patrols into Japanese areas. By this time, the Komori Force had lost at least 65 killed, 75 wounded, and 14 missing. This was from their attacks and the Director Task Force's attacks. The Japanese also had severe supply shortages and an outbreak of dysentery.

The Director Task Force launched its attack on January 16. That morning, B-24 Liberator heavy bombers dropped 136 bombs on Japanese defenses. 20 B-25s fired at the area. After heavy artillery and mortar fire, the Marine tank company, two companies of the 158th Infantry, and C Troop, 112th Cavalry Regiment, attacked. The tanks led the way, followed by infantrymen. The cavalry troop and three tanks were held back at first. But they were sent in at 12:00 to clear a Japanese position. The attack was successful and reached its goals by 16:00. Cunningham then ordered the force to go back to the MLR. During this, two Marine tanks that were stuck were destroyed. This was to stop the Japanese from using them as pillboxes. American engineers destroyed the Japanese defense position the next day. The Director Task Force had 22 killed and 64 wounded. They estimated 139 Japanese had been killed.

After the American attack, Komori pulled his remaining force back. They went to defend the airstrip. This was not an Allied goal. So, the Japanese were not attacked by ground troops again, except for occasional patrols and ambushes. Due to supply shortages, many Japanese soldiers became sick. Attempts to bring supplies by sea from Gasmata were stopped by U.S. Navy PT boats. The force also lacked enough porters to bring supplies by land. Komori believed his force was useless. On February 8, he told his superiors it would be destroyed due to lack of supplies. They ordered Komori to hold his positions. His force was even given two Imperial awards for supposedly defending the airstrip well.

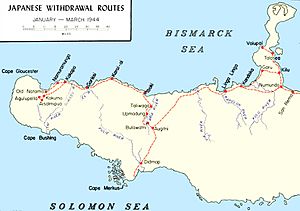

After the Battle

The 1st Marine Division's landing at Cape Gloucester on December 26, 1943, was successful. The Marines quickly secured the airfields, which were the main goal, by December 29. They faced only light Japanese resistance. Heavy fighting happened in the first two weeks of 1944. The Marines moved south to secure Borgen Bay. Little fighting occurred after this area was captured. The Marines patrolled widely to find the Japanese. On February 16, a Marine patrol from Cape Gloucester met an Army patrol from Arawe at Gilnit village. On February 23, the remaining Japanese force at Cape Gloucester was ordered to retreat to Rabaul.

The Komori Force was also ordered to retreat on February 24. This was part of the general Japanese withdrawal from western New Britain. The Japanese immediately left their positions. They headed north along inland trails to join other units. The Americans did not notice this retreat until February 27. An attack by the 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, and the Marine tank company found no Japanese. The Director Task Force then set up observation posts along New Britain's southern coast. They also increased the range of their patrols.

Komori fell behind his unit. He was killed on April 9 near San Remo on New Britain's north coast. He, his executive officer, and two soldiers were ambushed by a patrol. This was from the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. This unit had landed around Volupai and captured Talasea in early March.

The Japanese force at Arawe had many more casualties than the Allies. The Director Task Force lost 118 dead, 352 wounded, and four missing. Most of these were from the 112th Cavalry Regiment. They had 72 killed, 142 wounded, and four missing. Japanese casualties were 304 killed and three captured.

After the Japanese left, the Director Task Force stayed at Arawe. The 112th Cavalry kept improving the defenses. The regiment also trained. Some men got leave to Australia and the United States. Combat patrols continued in the Arawe region. They searched for any remaining Japanese soldiers. Parts of the 40th Infantry Division began arriving in April 1944. They took over guarding the area. The 112th Cavalry Regiment was told it would go to New Guinea in early June. The Director Task Force was then ended. The regiment sailed for the Aitape area of New Guinea on June 8. They next fought in the Battle of Driniumor River. The 40th Infantry Division kept a force at Arawe until the Australian Army's 5th Division took over New Britain in late November 1944.

Historians still debate if the Arawe operation was worth it for the Allies. The official history of the USMC says that having two experienced Japanese battalions at Arawe made the Marines' job at Cape Gloucester easier. However, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that "Arawe was of small value." He said the Allies never used it as a naval base. He also thought the soldiers stationed there could have been used better elsewhere. The U.S. Army's official history concluded that the landings at Arawe and Cape Gloucester "were probably not essential" to defeating Rabaul or moving towards the Philippines. But it also said the attacks in western New Britain had some benefits and did not cause "excessively high casualties."