Battle of Calais facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Calais |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

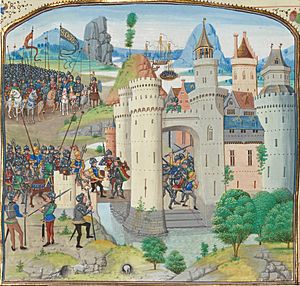

Geoffrey de Charny (left) and King Edward III of England (right) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,500 | At least 900 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 400 | Light | ||||||

The Battle of Calais happened in 1350. An English army defeated a French army that was trying to secretly capture the city of Calais. Even though there was a truce (a temporary stop to fighting), the French commander, Geoffrey de Charny, planned to take the city by trickery. He bribed Amerigo of Pavia, an Italian officer in the city's English army, to open a gate for the French.

The English king, Edward III, found out about the plan. He personally led his best knights and the Calais soldiers in a surprise attack. The smaller English force completely defeated the French. Many French soldiers were killed, and all their leaders were captured or died.

Later that day, King Edward dined with the captured French leaders. He treated them politely, except for Charny. Edward criticized Charny for breaking the rules of chivalry by fighting during a truce and trying to buy his way into Calais instead of fighting fairly. Charny was known as a perfect knight, so these accusations were very upsetting to him. The English often used this story in their propaganda (information used to promote a cause), especially since Charny wrote several important books about chivalry.

Two years later, Charny was freed after his ransom was paid. He was put in charge of a French army near Calais. He used this army to attack a small fort led by Amerigo. Amerigo was captured and taken to Saint-Omer. There, he was publicly punished severely for his betrayal.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Hundred Years' War Begins

Since 1066, English kings had owned lands in France. This made them vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. But there were many disagreements between Philip VI of France and Edward III of England. On May 24, 1337, the French King's council decided to take back the lands Edward held in France. They said Edward had broken his duties as a vassal. This decision started the Hundred Years' War, a conflict that lasted 116 years.

Calais: A Key Port

After nine years of fighting, King Edward landed his army in northern Normandy in July 1346. He led a large raid through Normandy, even capturing the city of Caen. After a big battle at Crécy, where the French lost many soldiers, Edward needed a safe port. He wanted a place where his army could gather and get supplies from the sea. The port of Calais on the English Channel was perfect.

Calais was very strong. It had two moats, thick city walls, and a citadel (a strong fortress) with its own moat. It would be a secure entry point into France for English armies. Supplies could easily come by sea, and the city was easy to defend by land.

Edward's army began to surround Calais in September 1346. The French king, Philip, could not help the city. The people inside Calais were starving, so they surrendered on August 3, 1347. Calais was the only large town successfully captured by either side in the first 30 years of the war.

A Temporary Truce

After more fighting, both sides were running out of money. Pope Clement VI sent people to help them make peace. Negotiations started in September, and by the 28th, the Truce of Calais was agreed upon. This truce was meant to stop the fighting for a while. It was good for the English, as it let them keep all the land they had captured. The truce was supposed to last nine months but was extended many times until 1355. However, it did not stop small naval battles or fighting in other areas like Gascony and Brittany.

Amerigo's Betrayal

Calais was very important for England during the war. It was almost impossible to land a large army in France without a friendly port. Edward had been lucky in 1346. Before that, in 1340, his forces had to fight a larger French fleet just to get to the port of Sluys. Having Calais also allowed the English to gather supplies before a campaign.

Calais had a very strong group of 1,200 soldiers, almost a small army. They were led by the captain of Calais. One of his officers was Amerigo of Pavia. Amerigo was in charge of a tower overlooking Calais's harbor. This tower had an entrance to the city's citadel.

Geoffrey de Charny was a respected Burgundian knight serving France. In 1347, when the French army tried to help Calais during the siege, they found the English too strong to attack. Charny was one of the knights who challenged Edward to fight in the open. But the French had to leave in shame, and Calais surrendered the next day. In July 1348, Charny was put in charge of all French forces in the northeast.

Charny learned that Amerigo had once served the French. He decided to approach Amerigo about betraying Calais for money. Since the truce was in place, it was easier to make contact. Charny thought that because Amerigo was not English and was of lower rank, he would be more likely to accept a bribe. In mid-1349, Charny agreed to pay Amerigo 20,000 écus (a large sum of money) to open the gate under his control. They met in person to finalize the deal.

King Edward found out about the plot around December 24. He met with Amerigo near London on that day. Edward quickly gathered 900 men—300 knights and 600 archers—and sailed for Calais with Amerigo. To keep the plan secret, the expedition was officially led by Sir Walter Manny. Amerigo's brother was kept in England to make sure Amerigo cooperated.

French Plans for a Surprise Attack

Meanwhile, Charny had gathered about 5,500 men at Saint-Omer, about 25 miles (40 km) from Calais. This force included 1,500 knights and 4,000 foot soldiers. They planned to attack the 1,200 English soldiers in Calais. Charny needed a large force to overcome the strong English defenders once inside the town.

The gate Amerigo controlled was hard to reach for a large army. It could only be reached on foot at low tide along a narrow beach next to the town walls. Getting to the gate was difficult because Calais was surrounded by large marshes. The few roads through the marshes were guarded by English blockhouses (small forts).

The French decided to attack on New Year's Eve. The night would be long, and low tide would be just before dawn. They hoped the English guards would be celebrating or asleep. They planned to go around the blockhouses and reach Calais before dawn. Most of the French army would wait nearby. A smaller group of 112 knights would enter through Amerigo's gate at night. Some would secure the citadel, while others would go through the sleeping town to the Boulogne Gate, one of the main gates. They would capture the gatehouse, open the gate, and then the main French army, led by mounted knights, would rush in and overwhelm the English.

The leader of the group entering through Amerigo's gate was Oudart de Renti. He was a French knight who had once joined the English but was later pardoned by the French king. Charny chose him because he knew the area around Calais very well.

The Battle of Calais

Charny's army marched towards Calais on the evening of December 31, 1349. They bypassed the English blockhouses and gathered near Calais. A little before dawn, the advance party approached Amerigo's gate-tower. The gate was open, and Amerigo came out to meet them. He gave his son to the French as a hostage and received the first part of his bribe. He then led a small group of French knights into the gatehouse.

Soon, a French flag was raised on top of the gatehouse tower. More French soldiers started to cross the drawbridge over the moat. Suddenly, the drawbridge was pulled up, and a portcullis (a heavy iron gate) fell in front of the French. Sixty English knights surrounded them. All the French soldiers who had entered the gatehouse were captured.

At the sound of a trumpet, the Boulogne Gate opened. King Edward, wearing plain armor and fighting under Walter Manny's flag, led his personal soldiers out. A group of archers supported them. They attacked the French. Many of Charny's soldiers cried "Betrayed!" and fled.

Charny quickly organized his remaining troops and fought back against the first English attack. King Edward himself had a tough fight. Edward's oldest son, the Black Prince, led his own knights out of the north gate, called the Water Gate. They went along the beach, past the citadel, and attacked the French army from their left side. As Edward and Charny's forces fought, the Calais soldiers, who didn't know about the plan, quickly armed themselves. They steadily joined Edward's group, which was fighting hard.

Charny's force still had more soldiers than the English. But they broke and ran when the Black Prince's force attacked. More than 200 French knights were killed in the fighting. Thirty French knights were taken prisoner. We don't know how many French foot soldiers died, as their deaths were often not recorded. Many who fled through the marshes drowned. The total French casualties are not certain, but historians say "several hundred." No important English soldiers were killed, so their casualties were not recorded.

The King and his son were at the front of the fighting. Important English nobles involved included the Earl of Suffolk, Lord Stafford, Lord Montagu, Lord Beauchamp, Lord Berkeley, and Lord de la Warr. Among the French captured were Charny, who had a serious head wound, Eustace de Ribemont, and Oudart de Renti. These were three of the main French commanders in Picardy. Pépin de Wierre was killed.

What Happened Next

Captured knights were seen as the personal property of their captors. They could be ransomed for large sums of money. Since King Edward had fought in the front lines, he claimed many of the prisoners as his own, including Charny. Edward gave Charny's captor a reward of 100 marks.

That evening, Edward invited the higher-ranking captives to dine with him. He revealed that he had fought them in disguise. He spoke pleasantly with everyone except Charny. Edward criticized Charny for abandoning his chivalric principles by fighting during a truce and trying to buy his way into Calais instead of fighting fairly. Charny was known as a perfect knight and had written books about chivalry. These accusations were a clever move in the ongoing propaganda war between England and France. The whole event was so embarrassing for the French that they rarely spoke about it.

Ribeaumont was quickly released on parole (a promise to return). This way, King Philip would hear a firsthand account of the disaster. Ribeaumont later returned to England to surrender himself until his ransom was paid. Most prisoners were released on the promise not to fight until their ransom was paid. Charny had to wait 18 months for his ransom to be fully paid before he was released. The amount is unknown, but King John II, Philip's son and the new king, paid part of it. During his captivity, Charny wrote much of his famous Book of Chivalry. In it, he warned against using "cunning schemes" instead of actions that are "true, loyal and sensible."

Amerigo was allowed to keep the money he had received from Renti. He soon returned to Italy. The fate of his son, who was taken by the French, is not known.

Charny's Revenge

In late 1350, Raoul, Count of Eu, a high-ranking French officer, returned after more than four years as an English prisoner. He was on parole from Edward, waiting to hand over his ransom. His ransom was set at a very high 80,000 écus, which Raoul could not afford. So, it was agreed that he would instead hand over the town of Guînes, which he owned. This was a common way to settle ransoms. Guînes had a very strong keep (main tower) and was a key French fort around Calais. If the English had it, Calais would be much safer from surprise attacks.

The new French king, John II, was angry about this attempt to weaken the blockade of Calais. He quickly had Raoul executed for treason. This act, where the king interfered in a nobleman's personal affairs, especially one so important, caused a big uproar in France. Charny had served under Raoul and was related to him, but his thoughts on the situation are not known. The English used this event in their diplomatic and propaganda efforts.

In early January 1352, a group of English soldiers captured Guînes by climbing its walls at midnight. The French were furious. The acting commander was severely punished for failing his duty at Charny's command. A strong protest was sent to Edward. This put Edward in a difficult spot because it was a clear breach of the truce. Keeping Guînes would mean losing honor and restarting the war, which he was not ready for. He ordered the English soldiers to give it back.

However, the English parliament (a meeting of important people) was set to meet the next week. Several members of the King's Council gave fiery speeches, wanting war. The parliament agreed to approve war taxes for three years. Feeling he had enough money, Edward changed his mind. By the end of January, the Captain of Calais had new orders: to take over guarding Guînes for the King. And so, the war began again.

The English had been making Calais's defenses stronger by building fortified towers at narrow points on the roads through the marshes. With the war restarted, Amerigo returned to English service. He was given a position of responsibility, but not one where his betrayal could cause a huge disaster. He was put in charge of a new tower at Fretun, about 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Calais.

The main French effort in this new round of fighting was against Guînes. Geoffrey de Charny was again put in charge of all French forces in the northeast. He gathered an army of 4,500 men against the English garrison of 115. He recaptured the town, but despite fierce fighting, he failed to take the keep. In July, the Calais garrison launched a surprise night attack on Charny's army. They killed many Frenchmen and destroyed their siege works (structures used to attack a fort).

Soon after, Charny stopped the siege of Guînes. He marched his army to Fretun and launched a surprise night attack on July 24/25. The night watch fled when attacked by an entire French army. According to one account, Amerigo was found still in bed. Charny took him to Saint-Omer, where he dismissed his troops. Before they left, they gathered with people from miles around to watch Amerigo being tortured to death with hot irons and cut into pieces with an axe. His remains were displayed above the town gates. Charny did not put soldiers in Fretun or destroy it. This was to show that his attack was a personal matter with Amerigo, and he had acted honorably by leaving the tower for the English to reoccupy.

Charny was killed in 1356 at the Battle of Poitiers. In that battle, the French royal army was defeated by a smaller English force led by the Black Prince, and King John was captured. Charny died holding the Oriflamme, the French royal battle banner. This fulfilled his oath to die before giving up the banner. Calais remained in English hands until 1558.

|

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |