Bruce campaign in Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bruce campaign in Ireland |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First War of Scottish Independence | |||||||

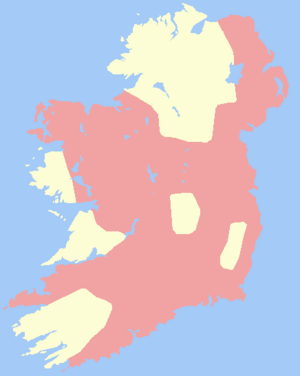

The Lordship of Ireland (pink) c. 1300 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

c. 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Bruce campaign was a three-year war in Ireland led by Edward Bruce. He was the brother of Robert the Bruce, who was the King of Scotland. The campaign started when Edward landed in Larne in 1315. It ended with his defeat and death in 1318 at the Battle of Faughart in County Louth.

This war was part of a bigger conflict called the First War of Scottish Independence against England. It also involved the ongoing fight between the native Irish people and the Anglo-Normans who had settled in Ireland.

Contents

Why the Scots Invaded Ireland

After winning the Battle of Bannockburn, King Robert the Bruce wanted to continue his war against England. He decided to send his younger brother Edward to invade Ireland.

Some native Irish leaders asked Robert for help. They wanted to drive the Anglo-Normans out of Ireland. In return, they offered to make Edward Bruce the High King of Ireland.

Another reason for the invasion was that some enemies of the Scottish king had fled to Ireland. These were supporters of the House of Balliol, who were rivals for the Scottish throne.

The Scottish leaders also thought that invading Ireland would make England use up its soldiers, supplies, and money. This would weaken England's war effort.

Edward Bruce and his brother Robert dreamed of a "grand Gaelic alliance" against England. They hoped that Scotland and Ireland, which shared history, language, and culture, could work together.

Ireland Before the Invasion

By the early 1300s, Ireland had not had a single high king for a long time. The last one, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair, had been removed from power in 1186.

The Plantagenet dynasty of England believed they had a right to control Ireland. This claim came from a special document from the Pope called Laudabiliter in 1155. England already ruled much of the eastern part of the island.

Ireland was split between the native Gaelic families and the Hiberno-Norman lords who had come from England and France. In 1258, some Gaelic nobles chose Brian Ua Néill as high king. But he was defeated by the Normans in 1260.

The Invasion Begins in 1315

In 1315, King Robert the Bruce sent his brother Edward to Ireland. Edward's invasion fleet gathered at Ayr in Scotland, which is close to Antrim in Ireland.

On May 26, 1315, Edward and his army of over 5,000 men landed on the Irish coast near Larne. His brother, King Robert, had sailed to the Western Isles to bring them under his control.

Early Victories and Alliances

Edward's army was met by forces loyal to the Earl of Ulster, including families like the de Mandevilles and Savages. However, the Scots, led by Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray, defeated them. After this victory, the Scots took the town of Carrickfergus, but not its castle.

In early June, Domnall Ó Néill, the King of Tyrone, and other northern Irish kings met Edward Bruce at Carrickfergus. They promised to be loyal to him as the new King of Ireland. The Irish records say that Bruce "took control of all of Ulster without anyone fighting back." They agreed to him being called King of Ireland.

Marching South: Battles and Retreats

In late June, Edward's army marched south from Carrickfergus. They burned towns like Rathmore and attacked Dundalk on June 29. Dundalk was almost completely destroyed, and many people were killed.

In July, two armies against Bruce gathered south of Ardee. One was led by Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster and his ally, Felim mac Aedh Ua Conchobair, the King of Connacht. The other army came from Munster and Leinster, led by Edmund Butler.

Bruce's army was ten miles north. Bruce avoided a direct battle and instead retreated north to Coleraine with Ó Néill. They burned Coleraine and destroyed its bridge. De Burgh's army followed, but both sides ran low on food. Bruce could get supplies from local Irish lords. De Burgh eventually pulled back to Antrim, and Butler returned home.

Bruce also sent messages to King Felim and a rival, Cathal Ua Conchobair, promising to help them if they left the fight. Cathal returned to Connacht and declared himself king. This forced Felim to go back to deal with the rebellion.

In August, Bruce's army crossed the river Bann. De Burgh retreated further to Connor. On September 1 or 9, the Scots-Irish army attacked and defeated de Burgh. William Liath, a relative of de Burgh, was captured and taken to Scotland as a hostage. De Burgh went back to Connacht, and other Anglo-Irish lords hid in Carrickfergus Castle.

King Edward II finally understood how serious the situation was. He ordered a meeting of Anglo-Irish leaders in Dublin in October, but they didn't take strong action.

On November 13, Bruce marched south again, attacking towns like Dundalk and Kells. At Kells, he met Roger Mortimer, who had gathered a large force. Bruce was also joined by new troops from Scotland. The Battle of Kells was fought on November 6 or 7. Bruce won a big victory. Mortimer had to retreat to Dublin and then sailed to England to ask King Edward II for more soldiers.

After Kells, Bruce continued to burn and raid towns like Granard and Abbeylara. He spent Christmas at Loughsewdy, using up all its supplies and then burning it down. Only the lands of Irish lords who joined him, or a few friendly Norman families, were left untouched.

Asking the Pope for Help

In 1317, Domhnall Ó Néill, the King of Tyrone, and Edward's Irish allies sent a formal complaint, called a remonstrance, to Pope John XXII. They asked the Pope to cancel the old document Laudabiliter, which gave England a claim to Ireland. They also mentioned Edward Bruce as the rightful King of Ireland. The Pope did not agree to their request.

The letter said that they had chosen Edward Bruce as their king because he was "pious and prudent, humble and chaste, exceedingly temperate." They believed he could free them from English rule and restore the Church's rights in Ireland.

This 1317 Remonstrance is very similar to the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, which was also sent to Pope John XXII by the Scots, complaining about how England treated them. Some historians believe the Scottish Declaration used ideas from the Irish Remonstrance.

The End of the Campaign

After several years of fighting, Bruce and his allies could not hold onto the areas they had conquered. His army lived by taking food and supplies from the land, which made them very unpopular with the local people.

A terrible time called the Great Famine of 1315–1317 affected all of Europe, including Ireland. Food became very scarce. Disease also spread widely in Bruce's army, making it smaller and weaker.

Finally, at the end of 1318, Edward Bruce was defeated and killed at the Battle of Faughart in County Louth. This battle marked the end of his campaign in Ireland.

The Bruce Campaign in Stories

The Bruce campaign is sometimes mentioned in stories about the Wars of Scottish Independence.

- It is described in parts of The Brus, a long poem written by John Barbour between 1375 and 1377.

- In Nigel Tranter's novel The Price of the King's Peace, the campaign is described in detail.

- The invasion of 1315 is also the setting for a series of novels by Tim Hodkinson, including Lions of the Grail and The Waste Land.

Sources

- Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, GWS Barrow, 1976.

- Annals of Ireland 1162–1370 in Britannia by William Camden; ed. Richard Gough, London, 1789.

- Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329, Sean Duffy, 2004.

- The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, Ian Mortimer, 2004.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |