Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee facts for kids

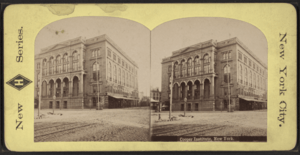

After slavery ended in the United States, many African Americans wanted to help end slavery elsewhere. They looked to Cuba, where a war was happening to stop slavery. They were not happy that U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant chose to stay neutral in this war. In 1872, African American men in New York formed a group to support ending slavery in Cuba. They also wanted the U.S. to officially recognize the Cuban rebels as a real fighting force. This group was called the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee. Its first meeting was in December 1872 at the Cooper Institute in New York City. Samuel R. Scottron led the Committee, and Reverend Henry Highland Garnet was its secretary and main speaker.

Contents

What Was Happening in Cuba?

In 1868, people in Cuba were very unhappy with Spain, which ruled the island. They also wanted to end slavery. This led to a civil war called the Ten Years' War, which lasted from 1868 to 1878. Cuban rebels fought against the Spanish army for independence and to abolish slavery. The United States had just finished its own Civil War and ended slavery. Many thought the U.S. might help the Cuban rebels. Many Cuban leaders and anti-slavery activists came to New York and Florida to ask for American help.

Why the U.S. Didn't Intervene

President Ulysses S. Grant and his team were divided on whether to get involved. Some, like Secretary of War John Rawlins, wanted to help Cuba. Others, like Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, were against it. They felt the U.S. had just finished its own war and shouldn't jump into another. They also worried about how Cuba would govern itself. So, President Grant offered to help Spain and the Cuban rebels talk. He said the U.S. would help if Cuba became independent and slavery ended there. But the U.S. did not get involved in the fighting.

How the Committee Started

Many formerly enslaved people were escaping from Cuba and coming to the U.S. This inspired Henry Highland Garnet and others to form the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee. Garnet and his friends supported the Cuban movement because it included people of all races. They hoped this could be a model for racial equality in the U.S. The first meeting was in Manhattan at the Cooper Institute. Another meeting soon followed in Boston.

The first meeting had mostly African American men and some Cuban exiles. Reporters, politicians, and leaders also attended, making sure the event was widely known. Garnet gave a powerful speech that everyone enjoyed. The meeting led to the Committee's main goal: to collect signatures across the country to support ending slavery in Cuba. They planned future meetings in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, and Washington D.C.. They also worked to educate people about the cause.

What the Committee Wanted to Achieve

The Committee's main goal was to get the U.S. to recognize and support the Cuban rebels. They saw the war in Cuba as a fight against slavery and old-fashioned colonialism. They believed this fight would affect the whole region. Because the Cuban rebel forces included people of different races, the Committee saw it as a great example of people working together.

A big reason for the Committee members' work was their belief that fighting for freedom abroad would help bring more racial equality at home. Even though African Americans were free from slavery, they still faced unfair treatment and segregation in the U.S. They felt their victories were not complete. They thought that winning civil liberty battles in other countries would set a strong example for how people should be treated in the U.S. African Americans also felt it was their country's duty to fight for freedom everywhere, based on the ideas in the Emancipation Proclamation.

Reverend Garnet especially believed that slavery was not truly defeated until it was gone from everywhere. He felt that the work of African American activists was not done until slavery was completely ended in the Americas. For him, the Cuban revolution was a continuation of the fight against slavery that had recently succeeded in the U.S.

Important Members of the Committee

Samuel Raymond Scottron was a founder and leader of the Committee. Born around 1843, Scottron was a well-known African American in New York City. He is famous for inventing the curtain rod. He worked for civil rights his whole life until he passed away on October 14, 1908.

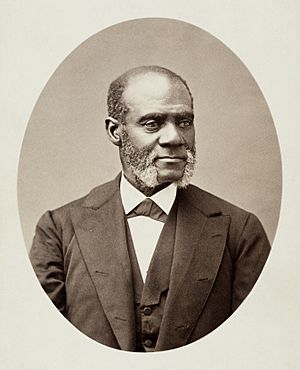

Henry Highland Garnet was the Committee's secretary and a founding member. He was born into slavery on December 23, 1815. He gained his freedom with his family and grew up in New York City. Garnet graduated from the Oneida Institute in 1840 and became a Presbyterian minister. He died on February 12, 1882, while serving as the U.S. Minister to Liberia. His life was dedicated to fighting racial inequality in the U.S. and other countries.

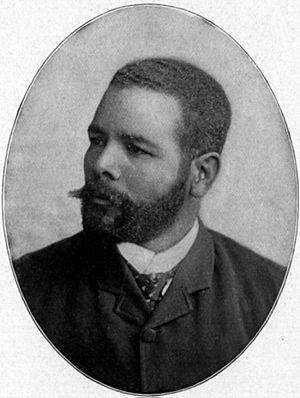

P.B.S. Pinchback was another key leader. He fought for the Union Army during the Civil War. He later became the first African American governor in the United States, serving in Louisiana.

Efforts to Influence Politics

A week before meeting with the President, Scottron held a meeting in Baltimore at the Madison Street (Colored) Presbyterian Church. There, he continued to gather signatures for the Committee's petition to Congress. This meeting was also important because many local women attended, showing equality within the movement.

Garnet and other Committee members presented thousands of signatures from New York and other cities to President Grant and Congress. President Grant met with the Committee's group. However, after talking with his advisors, the Grant administration decided not to take action. This disappointed Garnet and the Committee.

Other members who went to the White House included Scottron, George Downing, and J.M. Langston. It's thought that the petition might have had more than 5,000 names, possibly even tens of thousands.

The Committee's petition asked the U.S. Government to recognize the Cuban rebels fighting for independence. At the White House, Henry Turner, a Committee member, made it clear that the thousands of people who signed the petition were ready to join the Cuban rebels to overthrow Spain and end slavery.

The petition given to President Grant sparked a larger movement across the country. It gathered signatures estimated from tens of thousands to half a million. Events were held in cities like Sacramento, San Francisco, Virginia City (Nevada), New Orleans, Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Washington D.C..

The Committee felt that since the Cuban independence movement had been going on for four years, the rebels deserved American recognition and support.

Working with Cuban Revolutionaries

The Committee's leaders often talked with Cuban revolutionaries. They hoped to create a strong plan together. Important Cuban revolutionaries, like José Martí, admired the Committee's leaders, especially Garnet. Another big boost for the movement came when the famous Cuban general José Antonio Maceó met with leaders of the Committee's next organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Many prominent members from the original Committee were likely part of this meeting.

Spain's Response

The Spanish government was very worried about Americans supporting the Cuban rebels. They sent agents to watch and try to disrupt the Committee's meetings. These agents also handed out flyers warning Americans about the supposed dangers of supporting Cuban independence.

Lasting Impact

Political Influence

The Committee had a lasting impact on political movements of that time. Groups supporting Cuban freedom appeared across the country, including in Charleston, Key West, and Washington D.C.. Support for Cuban rebels was shown through official statements from groups like the California State Colored Men's Convention. Individual states also showed their support. The legislatures of Louisiana and Florida passed resolutions. The lieutenant governor of South Carolina, A. G. Ranier, often showed his support. Even after President Grant rejected their petition, the Committee's leaders kept working. They hoped the next president would support their cause. Public support continued, with a large meeting in Philadelphia a year later featuring Garnet. Eventually, the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee's leaders joined the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. They wanted to expand their fight for freedom beyond just Cuba.

The Ten Years' War and Beyond

The United States did not send its military to fight in the Ten Years' War. The Grant administration tried to negotiate a peaceful solution. These efforts mostly failed. As the war ended, the Grant administration set certain conditions for Spain to meet to keep American neutrality. Spain did not meet these demands. In 1878, Cuban rebels reluctantly signed the Pact of Zanjon, which ended the fighting and gave power back to Spain. A year later, Cubans started another rebellion called La Guerra Chiquita (the Little War), but they lost again. It wasn't until 1895, with the Cuban Revolutionary War, that rebels fought against Spain for independence once more. In 1898, the United States finally got involved in the Cuban Revolutionary War. Slavery officially ended in Cuba in 1886.

Spanish-American War

Four groups of African American soldiers were among the first units sent to Cuba when the Spanish-American War began. These soldiers faced serious segregation at home. They saw serving in the war as a great chance to help free enslaved people in Cuba. It was also a way to prove to America that they were equal citizens and deserved equal rights at home.

Many Americans were excited to go to war in Cuba. They wanted to help the Cuban people gain freedom and overthrow Spain. The idea of Cuban freedom and victory for oppressed people was a popular theme when the war started.