Hamilton Fish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

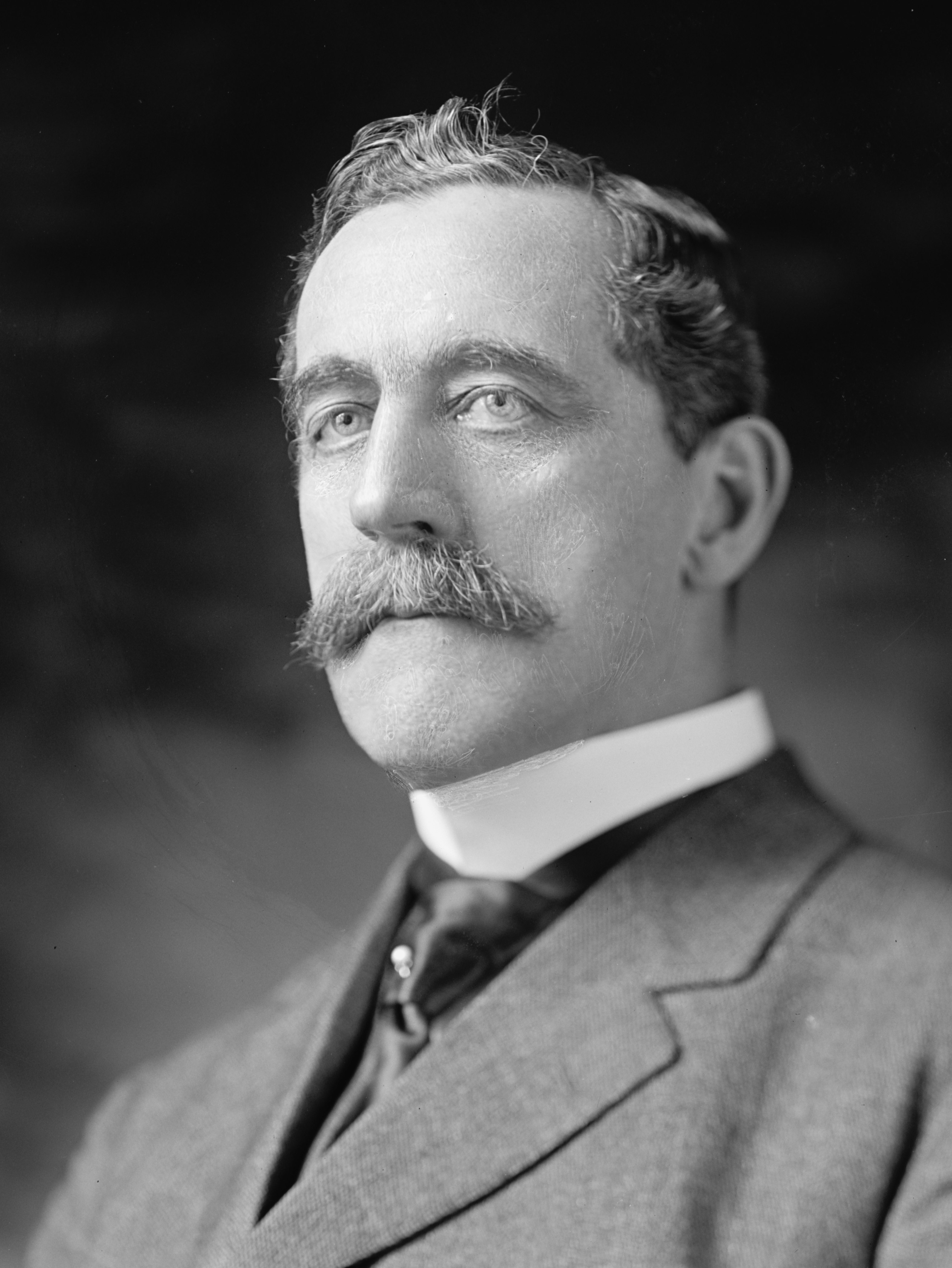

Hamilton Fish

|

|

|---|---|

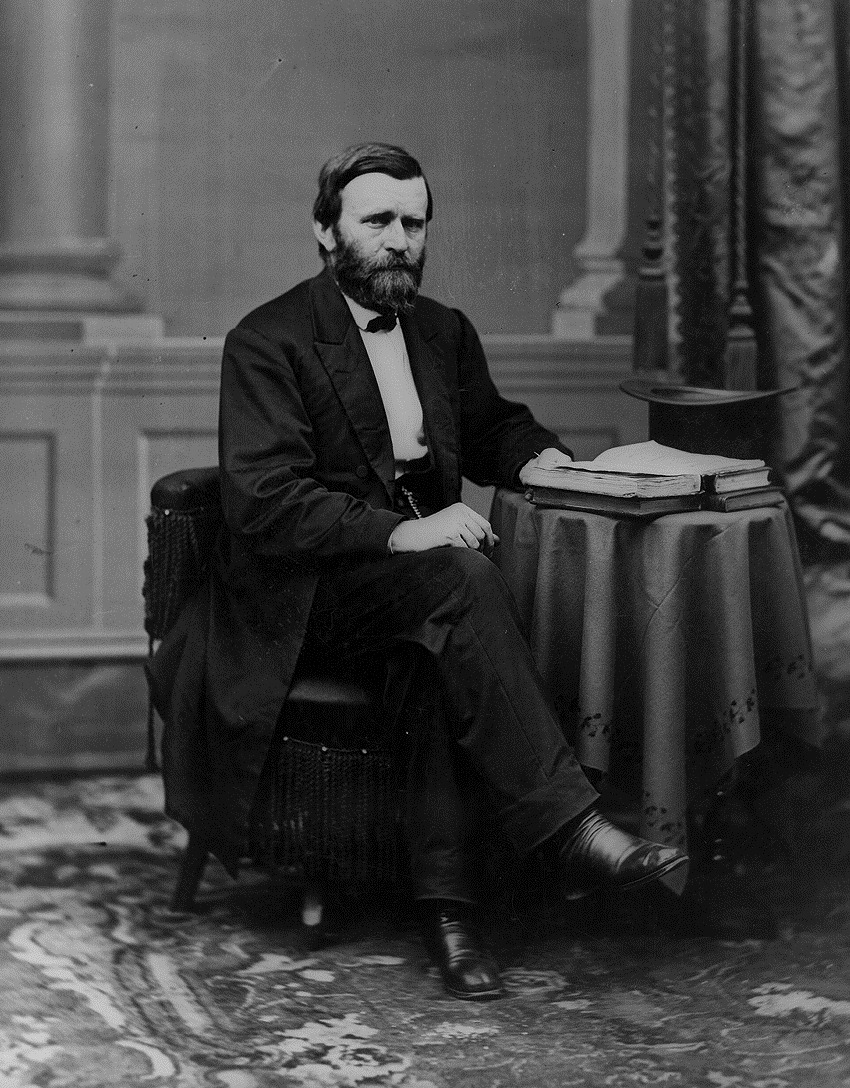

Photograph by Mathew Brady

|

|

| 26th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 17, 1869 – March 12, 1877 |

|

| President | Ulysses S. Grant Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Preceded by | Elihu B. Washburne |

| Succeeded by | William M. Evarts |

| United States Senator from New York |

|

| In office December 1, 1851 – March 3, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | Daniel S. Dickinson |

| Succeeded by | Preston King |

| 16th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1849 – December 31, 1850 |

|

| Lieutenant | George W. Patterson |

| Preceded by | John Young |

| Succeeded by | Washington Hunt |

| Lieutenant Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1848 – December 31, 1848 |

|

| Governor | John Young |

| Preceded by | Albert Lester (acting) |

| Succeeded by | George W. Patterson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 6th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1845 |

|

| Preceded by | James G. Clinton |

| Succeeded by | William Campbell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 3, 1808 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 7, 1893 (aged 85) Garrison, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1857) Republican (1857–1893) |

| Spouse | Julia Kean |

| Children | Sarah, Julia, Susan, Nicholas II, Hamilton II, Stuyvesant and Edith |

| Education | Columbia College (BA) |

| Signature |  |

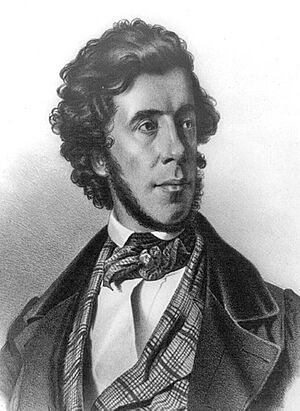

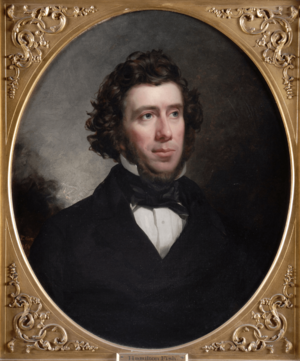

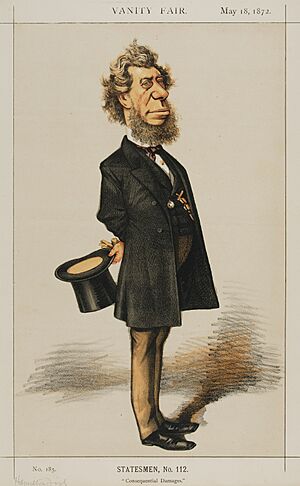

Hamilton Fish (born August 3, 1808 – died September 7, 1893) was an important American politician. He served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850. Later, he was a United States Senator for New York from 1851 to 1857. His most famous role was the 26th United States Secretary of State from 1869 to 1877.

Many historians see Fish as a key figure during Ulysses S. Grant's time as president. He is often called one of the best U.S. Secretaries of State. He was known for being fair and calm. Fish helped solve the famous Alabama Claims dispute with Great Britain. He did this by using a new idea called international arbitration, where countries settle disagreements through talks instead of fighting.

Fish also helped keep the United States out of war with Spain. This happened during the tense Virginius Affair over Cuban independence. In 1875, he helped set up a trade agreement with the Hawaiian Kingdom for sugar. He also arranged a peace meeting and treaty in Washington D.C. between South American countries and Spain. Fish worked with James Milton Turner, the first African American consul, to end the Liberian-Grebo War in 1876. President Grant trusted Fish's political advice more than anyone else's.

Fish came from a rich and well-known family in New York City. He went to Columbia College and became a lawyer. He started his political career in New York. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843. Later, he became Lieutenant Governor and then Governor of New York. In 1851, he was elected U.S. Senator. During the 1850s, he joined the Republican Party after the Whig Party broke apart. He was against slavery spreading to new areas.

After traveling in Europe, Fish supported Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860. During the American Civil War, he helped raise money for the Union. He also worked on a special commission that arranged prisoner exchanges between Union and Confederate soldiers. After the war, he returned to his law practice. In 1869, President Grant asked him to be Secretary of State. Fish worked hard to improve the State Department. He introduced civil service reform, which meant people had to pass tests to get government jobs. He handled many foreign policy challenges, including the Alabama claims and the Virginius incident. Fish retired from politics in 1877 and lived a quiet life until he died in 1893.

Historians praise Fish for his calm nature, honesty, and skill as a statesman. The Treaty of Washington, which settled the Alabama Claims, was a major success. He also skillfully handled the Virginius incident, preventing a war with Spain. Fish is often ranked as one of America's top Secretaries of State.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Marriage and Family Life

- New York Political Career

- Role in the American Civil War

- U.S. Secretary of State

- Reforming the State Department

- Cuban Rebellion and Relations with Spain

- Dominican Republic Annexation Treaty

- Colombian Canal Treaty

- Treaty of Washington (1871)

- South American Peace and Armistice

- Korean Expedition and Conflict

- The Virginius Affair (1873)

- Hawaiian Trade Treaty (1875)

- Liberian-Grebo War (1876)

- Later Life and Health

- Death and Burial

- Historical Reputation

- Society of the Cincinnati

- Notable Descendants

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

Hamilton Fish was born on August 3, 1808, in New York City. His family was very old and well-known in New York. His father, Nicholas Fish, was a famous politician and soldier during the American Revolutionary War. His mother, Elizabeth Stuyvesant, was a direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, who was a founder of New York when it was a Dutch colony. Hamilton was named after his parents' friend, Alexander Hamilton.

Fish went to a private school and then to Columbia College. He graduated in 1827 with high honors. At Columbia, he learned to speak French very well. This skill helped him later as Secretary of State. After college, he studied law and became a lawyer in 1830. He joined the Whig Party, following his father's political views. From 1831 to 1833, he worked as a commissioner of deeds for New York City. He tried to run for the New York State Assembly in 1834 but did not win.

Marriage and Family Life

On December 15, 1836, Hamilton Fish married Julia Kean. She was also from a well-known New York family. Their marriage was long and happy. Julia Fish was known for being wise and having good judgment. They had three sons and five daughters. Many of Hamilton Fish's children and later family members became famous in their own right.

New York Political Career

After his first attempt to run for office failed, Fish did not seek office for eight years. However, in 1842, leaders of the Whig Party convinced him to run for the United States House of Representatives.

Serving in the U.S. House

In November 1842, Fish was elected to the House of Representatives. He represented New York's 6th District from 1843 to 1845. During this time, the Whigs were a minority party in the House. Still, Fish gained important national experience by serving on the Committee of Military Affairs. He did not win re-election for a second term.

Lieutenant Governor of New York

In 1846, Fish ran for Lieutenant Governor of New York as a Whig candidate. He lost to Addison Gardiner. Gardiner was supported by the Anti-Rent Party, a group of farmers who refused to pay rent to landowners. Fish was against their violent methods.

In May 1847, Gardiner left the Lieutenant Governor's office to become a judge. Fish then ran again in November 1847 to fill the empty spot. He won and served as Lieutenant Governor in 1848. People thought highly of Lieutenant Governor Fish. He was known for being fair and firm in the New York Senate.

Governor of New York

In November 1848, Hamilton Fish was elected Governor of New York. He served from January 1, 1849, to December 31, 1850. At 40 years old, he was one of the youngest governors in New York's history.

As governor, Fish supported and signed laws for free public education across New York. He also pushed for building an asylum and school for people with intellectual disabilities. During his time, the canal system in New York state grew. He also suggested that the state collect and publish New York's old Colonial Laws. None of the bills Governor Fish refused to sign were overturned by the state legislature.

In his yearly speeches, Fish spoke out against slavery spreading into new lands gained from the Mexican–American War, like California and New Mexico. His anti-slavery views made him known nationally. President Zachary Taylor even considered him for a cabinet position, but Taylor died before he could nominate Fish. Despite his popularity, Fish was not chosen to run for governor again.

U.S. Senator for New York

After leaving the governor's office, Fish did not actively seek to become a U.S. Senator. However, his supporters nominated him in January 1851. There was a delay in his nomination because some senators were upset that Fish had not openly supported the Compromise of 1850. Fish had only said that the government should enforce laws. He did not favor the spread of slavery but was careful about supporting the Free Soil movement.

Finally, on March 19, 1851, Fish was elected a U.S. Senator from New York. He took his seat on December 1 and served alongside William H. Seward, who would also become Secretary of State later.

In the United States Senate, Fish was a member of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. He served on this committee until his term ended on March 4, 1857. During the later part of his term, he became a Republican. He was part of a group that was moderately against slavery. By 1856, Fish privately still thought of himself as a Whig, but he knew the Whig Party was no longer strong.

Fish was a quiet senator who preferred to work behind the scenes rather than give big speeches. He often disagreed with Senator Charles Sumner, who was strongly against slavery and pushed for equal rights for Black people. Fish believed in voting for laws that supported "justice, economy, and public virtue." He strongly opposed ending the Missouri Compromise, which had limited the spread of slavery. He also voted against the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed new territories to decide on slavery.

During his time as senator, the country faced huge political problems over slavery. In 1856, pro-slavery groups used violence in Kansas against those who opposed slavery. After his term ended, Fish traveled to Europe with his family. He returned to America just before the American Civil War began. While in France, he learned a lot about foreign policy from diplomats. This experience would be very helpful when he became Secretary of State.

Role in the American Civil War

Hamilton Fish played several important roles during the American Civil War. His private secretary was involved in the attempt to bring supplies to Fort Sumter on the ship Star of the West. Fish often met with General Winfield Scott, the commander of the U.S. Army. Fish was dining with Scott when they heard that Confederates had fired on the Star of the West. Fish said it meant war, but Scott replied, "Don't utter that word, my friend. You don't know what a horrid thing war is."

From 1861 to 1862, Fish was part of the "Union Defense Committee of the State of New York." This committee worked with New York City to raise and equip Union Army troops. They also gave over $1 million to help New York volunteers and their families. Fish became the chairman of this committee.

In 1862, President Lincoln appointed Fish as a commissioner to visit Union prisoners in Richmond, Virginia. The Confederate government did not allow them into the city. Instead, Fish helped start the prisoner exchange program, which continued throughout the war. After the war, Fish went back to being a lawyer in New York.

U.S. Secretary of State

Hamilton Fish became United States Secretary of State for President Ulysses S. Grant on March 17, 1869. He served for almost eight years, until March 12, 1877. He was President Grant's longest-serving cabinet member. When he started, some people didn't think he was very skilled. However, Fish quickly showed he was hardworking and smart. He had to deal with many foreign policy issues, including the Cuban rebellion and the Alabama Claims.

During the time after the Civil War, called Reconstruction, Fish did not always agree with Grant's policies to fight racism and help African Americans in the South. He sometimes found cabinet meetings boring when the Attorney General talked about the violence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Fish often thought about resigning, especially after the success of settling the Alabama Claims in 1871. But President Grant needed his advice and asked him to stay. Grant told Fish he couldn't find anyone to replace him. Fish, who was 13 years older than Grant, stayed in office even when he was not feeling well.

Reforming the State Department

When Fish became Secretary of State, he immediately started to improve the United States Department of State. He organized 700 volumes of old documents and created a new office called the Bureau of Indexes and Archives. Fish introduced a system to index files, making it easier to find documents.

He also brought in civil service reform. This meant that people applying for jobs in the State Department had to pass an exam. This helped improve the quality of the staff. Fish made sure his staff were disciplined and copied important messages quickly.

Before Fish, record-keeping was very old-fashioned. Countries were listed alphabetically, not by region. This made it hard and slow to prepare information for Congress. Also, diplomatic ministers (like ambassadors) were not kept up-to-date on world events happening in other regions.

Cuban Rebellion and Relations with Spain

By 1869, people in Cuba were openly fighting against Spain because they disliked Spanish rule. Many Americans supported the Cuban rebels. President Grant seemed ready to recognize the Cuban rebels as a fighting force. However, Fish did not want to do this. He was trying to settle the Alabama Claims with Great Britain. If the U.S. recognized the Cuban rebels, it would be like when Britain recognized the Confederate states during the Civil War. This could hurt the talks with Britain.

In February 1870, Senator John Sherman proposed that the Senate recognize the Cuban rebels. Fish quietly told Sherman that recognizing Cuba could lead to war with Spain. Fish worked with President Grant to send a special message to Congress. This message asked Congress not to recognize the Cuban rebels. On June 13, 1870, Congress decided not to recognize them. This policy helped avoid war with Spain, but it was tested again in 1873 during the Virginius Affair.

Dominican Republic Annexation Treaty

When President Grant took office in 1869, he was very interested in adding the Dominican Republic (then called Santo Domingo) to the United States. Grant believed this would increase America's resources and help with racism against African Americans in the South. Hamilton Fish, though loyal to Grant, was against adding Latin American countries. He felt it would cause many problems.

The Dominican Republic was facing civil unrest. Its leader, President Buenaventura Báez, had even put an American citizen in prison. Fish told Grant that the Senate probably wouldn't approve a treaty to annex Santo Domingo. In April 1869, Grant sent his private secretary, Orville Babcock, to the island. Babcock was a strong supporter of annexation.

In September 1869, Babcock made a first treaty to annex Santo Domingo. In October 1869, Fish wrote a formal treaty. It included paying the Dominican national debt and leasing Samaná Bay to the U.S. for a yearly payment. Santo Domingo would eventually become a U.S. state.

Charles Sumner, who led the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was against the treaty. He believed Santo Domingo should stay independent. He also felt that racism in the U.S. needed to be fixed at home. On January 10, 1870, Grant sent the treaty to the Senate. The Senate debated it for a long time and finally rejected it on June 30, 1870.

Grant was angry that Sumner didn't support the treaty. He fired Sumner's friend, who was the U.S. ambassador to England. Grant believed Sumner had promised to support the treaty. In 1871, Sumner lost his leadership position on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Colombian Canal Treaty

President Grant and Secretary Fish wanted to build a canal across Panama. On January 26, 1870, Secretary Fish helped sign a treaty in Bogota between the United States and Colombia. This treaty planned a route for the canal through Panama. However, the Colombian Senate changed the treaty so much that it lost its value for the U.S. Because of this, the United States Senate refused to approve the treaty.

Treaty of Washington (1871)

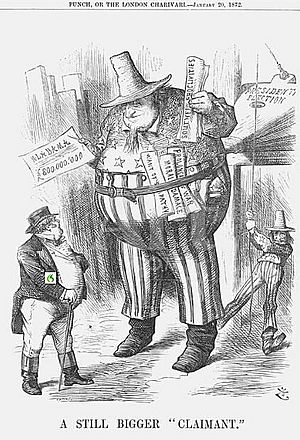

The Alabama Claims were a big problem after the American Civil War. Confederate ships, built in British ports (like the C.S.S. Alabama), had sunk many Union merchant ships. The U.S. wanted Britain to pay for the damages. Before Fish, a treaty to solve this was rejected by the Senate. Many Americans, led by Charles Sumner, were very angry at Britain. Sumner even demanded that Britain give Canada to the U.S. as payment.

In late 1870, a chance came to settle the claims with British Prime Minister William Gladstone. Fish wanted to improve relations with Britain. With President Grant's support, Charles Sumner was removed from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. This opened the way for new talks with Britain.

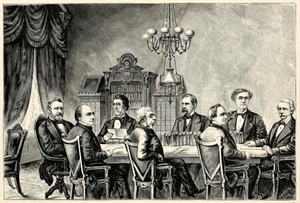

On January 9, 1871, Fish met with British representative Sir John Rose. They agreed to set up a Joint Commission to settle the Alabama Claims. This commission would meet in Washington and be led by Hamilton Fish. On February 14, 1871, important representatives from Britain and the U.S. met. The talks went very well. The Canadian Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald, also represented Britain.

After 37 meetings, the Treaty of Washington was signed on May 8, 1871. The Senate approved it on May 24, 1871. On August 25, 1872, an international group meeting in Geneva decided the U.S. would receive $15,500,000 in gold for the damages. The treaty also settled disputes over Atlantic fisheries and the San Juan Boundary (the border with Canada in the Oregon area). This treaty was a huge success. It solved border issues, trade, and navigation problems. It also created a lasting friendship between Great Britain and America. Britain even expressed regret for the damages caused by the Alabama.

South American Peace and Armistice

On April 11, 1871, Hamilton Fish led a peace and trade meeting in Washington D.C. It was between Spain and the South American countries of Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia. These countries had been technically at war since 1866. The United States, led by Fish, acted as a mediator.

The armistice treaty they signed had seven articles. It stated that fighting would stop for at least three years. It also allowed these countries to trade with neutral nations. This was a successful effort by Fish to bring peace to the region.

Korean Expedition and Conflict

In 1871, Korea was known as the "Hermit Kingdom." It wanted to stay isolated from other countries, especially from Western trade. In 1866, relations between the U.S. and Korea became difficult. Christian missionaries were killed by the Korean government, and the crew of a U.S. trading ship, the General Sherman, was massacred.

Secretary of State William H. Seward (before Fish) wanted action for these events. U.S. warships were sent to the area, but Seward left office before a naval expedition could be organized. When Fish became Secretary, he organized the Korean naval expedition. He expanded its goals to get justice for the sailors and to open a trade treaty with Korea. Fish told the fleet not to use force unless the U.S. flag's honor was threatened.

On May 8, 1871, Frederick F. Low, the U.S. minister to China, and Rear Admiral John Rodgers sailed to Korea with five warships. On May 16, they anchored near the mouth of the Han River. The Koreans tried to delay them. In June, Korean forts on the Han River fired on the American fleet while it was surveying. The American fleet fired back, damaging the forts. The Americans demanded an apology.

On June 10, a U.S. military force was sent to destroy the Korean forts on Kanghoa Island. The U.S.S. Monocacy bombed the forts. Then, 546 sailors and 105 marines landed and captured the forts. The "Citadel" fortress fought hard, with hand-to-hand combat. All the Korean forts were destroyed on June 11. Three hundred fifty Korean soldiers were killed, while only one American officer and two sailors died.

The American squadron stayed on the Han River for three weeks, but the Koreans still refused to negotiate a trade treaty. The Koreans believed they had won a great victory. The U.S. attempt to open Korea to trade was similar to how Commodore Matthew Perry opened Japan in 1854. However, Korea was more isolated than Japan. Later, in 1881, Commodore Robert W. Shufeldt, without a naval fleet, successfully made a commercial treaty with a more willing Korean government. The U.S. was the first Western nation to formally trade with Korea.

The Virginius Affair (1873)

In the 1870s, Cuba was rebelling against Spain. Many Americans wanted the U.S. to help the Cuban rebels. A private ship called the Virginius was used to carry guns and supplies to the rebels. On October 31, 1873, a Spanish warship, the Tornado, captured the Virginius in neutral waters near Jamaica. The 103 crew members included Cuban rebels and 52 American and British citizens. The Spanish took the prisoners to Santiago, Cuba.

The Spanish authorities executed 53 of the Virginius crew members. They only stopped when a British warship arrived, ready to fire on Santiago. At this time, the American Navy was not as strong as it had been during the Civil War.

When news of the executions reached the U.S., many Americans demanded war with Spain. President Grant and Secretary Fish had to act quickly. Fish discovered that the Virginius's American registration was fake. However, the executions of Americans still required a response. Fish handled the situation calmly. He met with the Spanish minister in Washington D.C., Admiral José Polo de Bernabé.

They reached an agreement. Spain gave the damaged Virginius to the U.S. Navy. The remaining 13 American survivors were released. The Spanish captain who ordered the executions was punished. Spain also paid $80,000 to the American families whose relatives were killed. Thanks to the calm actions of Fish and Bernabé, war between the U.S. and Spain was avoided.

Hawaiian Trade Treaty (1875)

Fish also worked out the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 with the Hawaiian Kingdom, led by King Kalākaua. This treaty made Hawaiian sugar duty-free (no taxes) when imported into the U.S. In return, American manufactured goods and clothing could be imported into Hawaii without taxes. By opening Hawaii to free trade, this treaty started the process that would eventually lead to Hawaii becoming a U.S. state.

Liberian-Grebo War (1876)

The U.S. helped settle the Liberian-Grebo War in 1876. Hamilton Fish sent the USS Alaska to Liberia under President Grant's orders. Liberia was like an American colony. James Milton Turner, the first African American ambassador, asked for a warship to protect American property there. With the U.S. Navy present, Turner helped negotiate peace. This led to the Grebo people joining Liberian society and foreign traders being removed from Liberia.

Later Life and Health

After leaving President Grant's cabinet in 1877, and briefly serving under President Hayes, Hamilton Fish retired from public office. He returned to his private life, practicing law and managing his properties in New York City. He was highly respected in New York and enjoyed spending time with his family.

Fish lived at Glen Clyffe, his estate near Garrison, New York. His health was generally good until around 1884, when he began to suffer from nerve pain.

Death and Burial

On September 6, 1893, Fish played cards with his daughter in the evening. The next morning, September 7, he died suddenly at the age of 85. His death was due to old age.

On September 11, 1893, Fish was buried in Garrison at St. Philip's Church-in-the-Highlands Cemetery. He was buried next to his wife and oldest daughter. Many important people attended his funeral.

Historical Reputation

Historians have praised Hamilton Fish for his calm nature under pressure, his honesty, loyalty, and modesty. They also admired his great skill as a statesman during his time with President Grant. The most important achievement of his career was the Treaty of Washington, which peacefully settled the Alabama Claims. Fish also handled the Virginius incident very well, preventing a war with Spain.

A survey of scholars in 1981 ranked Fish as one of the top three U.S. Secretaries of State. This was because of his work on the Alabama Claims, the peaceful settlement of the Virginius Incident, and his Hawaiian treaty.

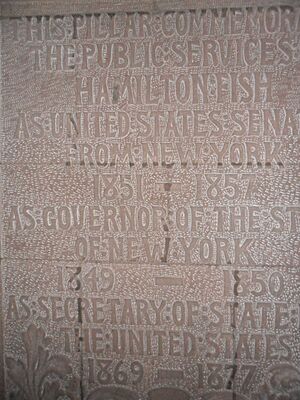

There is a memorial to Fish at the Cathedral of All Saints (Albany, New York). The Hamilton Fish Newburgh-Beacon Bridge, which crosses the Hudson River in New York, is named after him.

Society of the Cincinnati

Hamilton Fish was a long-time member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati. He joined because his father was an officer in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Fish became the Vice President General of the national Society in 1848. In 1854, he became its President General. He also became President of the New York Society in 1855. Fish held both of these leadership roles until he died in 1893. His 39 years as President General is the longest in the Society's history.

Notable Descendants

Three of Hamilton Fish's direct descendants, all named Hamilton, served in the U.S. House of Representatives for New York.

- Hamilton Fish II, his son, was a U.S. Representative from 1909 to 1911. He also worked as an assistant to his father when he was Secretary of State.

- Hamilton Fish III, his grandson, served as a U.S. Representative from 1920 to 1945.

- Hamilton Fish IV, his great-grandson, served as a U.S. Representative from 1969 to 1995.

Another son, Stuyvesant Fish, became an important railroad executive. Another son, Nicholas Fish II, was a U.S. diplomat. He served in Berlin, Berne (Switzerland), and Belgium. He later worked in banking in New York City.

Hamilton Fish's grandson (also named Hamilton Fish, son of Nicholas) fought in the Spanish–American War. He was one of the famous Rough Riders. He was the first member of that regiment to be killed in action, during the Battle of Las Guasimas in Cuba.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hamilton Fish para niños

In Spanish: Hamilton Fish para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |