E. Pauline Johnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

E. Pauline Johnson

|

|

|---|---|

E. Pauline Johnson, c. 1885–95

|

|

| Born | Emily Pauline Johnson 10 March 1861 Six Nations, Ontario |

| Died | 7 March 1913 (aged 51) Vancouver, British Columbia |

| Resting place | Stanley Park, Vancouver |

| Language | Mohawk, English |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Citizenship | Mohawk Nation British subject |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Notable works |

|

Emily Pauline Johnson (born March 10, 1861 – died March 7, 1913) was a famous Canadian poet, writer, and performer. She was also known by her Mohawk stage name Tekahionwake, which means "double-life." She was very popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Pauline Johnson's father was a Mohawk chief, and her mother was an English immigrant. Her poems and stories were published in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain. She helped shape what we know as Canadian literature today.

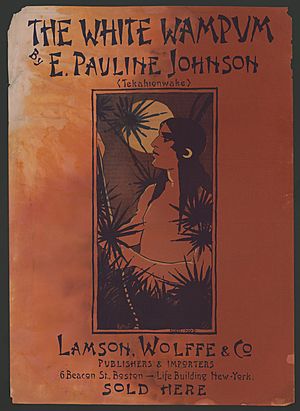

Johnson was special because her work celebrated her mixed heritage. She combined ideas from both Indigenous and English cultures. Some of her most famous books of poetry are The White Wampum (1895) and Flint and Feather (1912). She also wrote story collections like Legends of Vancouver (1911). After she passed away, people didn't talk about her work as much. But since the late 1900s, there has been new interest in her life and writings.

Contents

Her Family History

Pauline Johnson's father, Chief George Henry Martin Johnson, came from a Mohawk family. They used to live in what is now New York state in the United States. This area was part of the traditional lands of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League, also called the Haudenosaunee.

During the American Revolutionary War, many Mohawk people supported the British. Pauline's great-grandfather, Jacob Johnson, and his family moved to Canada. After the war, they settled in Ontario on land given to them by the British Crown.

Jacob's son, John Smoke Johnson, was good at speaking both English and Mohawk. He was also a great speaker. Because he showed loyalty to the British during the War of 1812, he became a Pine Tree Chief. His wife, Helen Martin, was from a founding family of the Six Nations reserve. Through her family line, their son George Johnson (Pauline's father) became a chief.

George Johnson was also good with languages. He worked as a translator for the Anglican Church on the Six Nations reserve. There, he met Emily Howells, the sister-in-law of the missionary he worked with.

Emily Howells was born in England. Her family moved to the United States in 1832. Her father was a Quaker who wanted to help end slavery. Emily moved to the Six Nations reserve in Ontario to live with her older sister. She helped her sister with her family. Emily fell in love with George Johnson. She started to understand Native peoples better and changed some of her earlier beliefs.

George and Emily married in 1853, even though their families were not happy about it at first. But when their first child was born, their families became friends again. In 1856, George Johnson built a large wooden house called Chiefswood on his land. This is where Pauline and her family lived for many years.

As a government interpreter and chief, George Johnson was known for helping Native and European people understand each other. He was respected in Ontario. However, he also made enemies by trying to stop illegal logging on the reserve. He was attacked and became very ill, passing away in 1884.

Her Life and Education

Early Life

Emily Pauline Johnson was the youngest of four children. She was born at Chiefswood, her family home on the Six Nations reserve in Ontario. Her mother, Emily Susanna Howells Johnson, was English. Her father, George Henry Martin Johnson, was a Mohawk chief.

Because her father worked as an interpreter and negotiator between the Mohawk, British, and Canadian governments, the Johnsons were important in Canadian society. Famous people like Alexander Graham Bell and The Marquess of Lorne visited their home.

Pauline's mother taught her children good manners. Her father encouraged them to learn about both their Mohawk and English backgrounds. Even though Pauline was legally considered Mohawk by British law, the Mohawk people have a matrilineal system. This means children belong to their mother's family. Since Pauline's mother was English, the Mohawk people did not consider Pauline to be part of a Mohawk family or clan.

Early Education

Pauline was often sick as a child, so she did not go to the Mohawk Institute Residential School. She mostly learned at home from her mother and governesses. She also read many books from her family's large library. She loved reading poems and stories about Indigenous people, which later inspired her own writing.

Even though racism against Indigenous people was common, Pauline and her siblings were taught to be proud of their Mohawk heritage. Her grandfather, John Smoke Johnson, told them traditional Indigenous stories. He taught them life lessons in Mohawk, which they understood but did not speak fluently. Pauline learned a lot from his dramatic storytelling. She later became known for her own powerful stage performances.

When she performed, Pauline sometimes wore items from her Mohawk grandparents, like a bear claw necklace. Later in life, she wished she had learned more about her grandfather's Mohawk language and culture.

Pauline went to Brantford Central Collegiate when she was 14 and graduated in 1877.

Her Relationships

Pauline Johnson had many people interested in her. Her sister said she received more than six marriage proposals from Euro-Canadians. However, Pauline never married. She chose to focus on her career and her heritage.

Pauline had a strong group of female friends who supported her. She believed these friendships were very important in her life.

She once said:

Women are fonder of me than men are. I have had none fail me, and I hope I have failed none. It is a keen pleasure for me to meet a congenial woman, one that I feel will understand me, and will in turn let me peep into her own life- having confidence in me, that is one of the dearest things between friends, strangers, acquaintances, or kindred.

Her Stage Career

In the 1880s, Pauline Johnson wrote and acted in plays for fun. After her father died in 1884, her family rented out Chiefswood. Pauline moved with her mother and sister to Brantford. She started performing on stage to earn money and support her mother until her mother's death in 1898.

In 1892, Pauline was invited to read her poetry at an event in Toronto. She was the only woman there. She recited her poem "Cry from an Indian Wife" to a huge crowd. People loved her performance and asked for an encore. This success started her 15-year career as a performer.

Pauline decided to highlight her Native heritage in her shows. She created a two-part act. In the first part, she appeared as Tekahionwake, wearing a costume that mixed different "Indian" items. She would recite dramatic poems about Indigenous life.

During an intermission, she would change into fashionable English clothes. In the second part, she would come out as a Victorian English woman and recite her "English" poems. Her shows were very popular, and she toured all over North America.

Her Writing Career

Pauline Johnson published her first long poem, "My Little Jean," in 1883. After that, she started writing and publishing more often.

In 1885, her poem "A Cry from an Indian Wife" was published. It was based on events from the North-West Rebellion. Pauline often used her Mohawk identity in her writing.

In 1886, she wrote a poem called "Ode to Brant" for the unveiling of a statue honoring Joseph Brant, an important Mohawk leader. Her poem was read at a large ceremony. It called for friendship between Native and white Canadians. This poem made people even more interested in Johnson's poetry and heritage.

Throughout the 1880s, Johnson became well-known as a Canadian writer. She published regularly in popular magazines. She was seen as one of the writers who were creating a unique Canadian literature.

After she stopped performing in 1909, Johnson moved to Vancouver, British Columbia. She continued to write articles for a newspaper called Daily Province. These articles were based on stories told by her friend Chief Joe Capilano of the Squamish Nation. In 1911, her friends helped publish these stories in a book called Legends of Vancouver. These stories are still famous in Vancouver today.

In her stories, Johnson used her mixed background as a main theme. For example, in "The De Lisle Affair" (1897), she showed how women sometimes had to hide their true selves to be safe. In "As It Was in the Beginning," her mixed-race character, Esther, says, "I am a Redskin, but I am something else, too – I am a woman." This shows that people can have many different parts to their identity. Johnson wanted to show that the world is more complex than simple ideas about race.

Her books The Shagganappi (1913) and The Moccasin Maker (1913) were published after she died. They are collections of stories that first appeared in magazines.

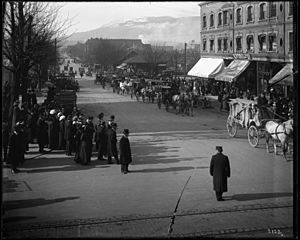

Her Death

Pauline Johnson died of breast cancer on March 7, 1913, in Vancouver, British Columbia. Her funeral was held on what would have been her 52nd birthday. It was the largest public funeral Vancouver had ever seen at that time. The city closed its offices, and flags flew at half-mast. Many people, including Squamish people, lined the streets to honor her.

Her ashes were placed in Stanley Park near Siwash Rock. This was arranged by the governor general, the Duke of Connaught. A monument was later built at her burial site in 1922. It says, "In memory of one whose life and writings were an uplift and a blessing to our nation."

Her Legacy

Canadian Literature

Pauline Johnson was a very important figure for Indigenous women writers and performers in Canada. Mohawk writer Beth Brant said, "Pauline Johnson's physical body died in 1913, but her spirit still communicates to us who are Native women writers. She walked the writing path clearing the brush for us to follow."

Many Indigenous writers have been inspired by Pauline Johnson. For example:

- In 1989, Joan Crate (Metis) wrote a book of poems called Pale as Real Ladies: Poems for Pauline Johnson.

- In 2000, Jeannette Armstrong (Okanagan) started her novel Whispering in Shadows with Johnson's poem "Moonset."

- In 2002, Janet Rogers (Mohawk) wrote a play called Pauline and Emily, Two Women, about Johnson and Canadian artist Emily Carr.

- In 1993, Shelley Niro (Mohawk) made a film that included a reading of Johnson's poem "The Song My Paddle Sings."

Canadian Government

In the 1800s and early 1900s, the Canadian government had unfair policies towards Indigenous Canadians. Children were forced to attend residential schools, and communities were confined to reserves. Pauline Johnson spoke out against some of these policies.

In her poem "A Cry From an Indian Wife," she wrote:

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men's hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low ...

Perhaps the white man's God has willed it so.

Because of laws like the Indian Act, Pauline Johnson was sometimes called a "halfbreed" in a disrespectful way.

Honors After Her Death

- 1922: A monument was built for Johnson in Stanley Park in Vancouver, BC.

- 1945: Johnson was named a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada.

- 1953: Chiefswood, her childhood home, became a National Historic Site. It is now a museum.

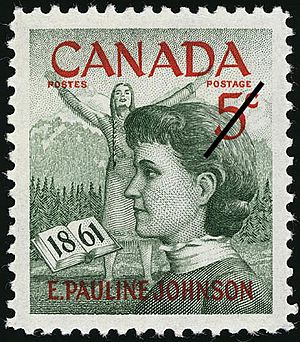

- 1961: On the 100th anniversary of her birth, Canada released a special stamp with her picture. She was the first woman (besides the Queen), the first author, and the first Indigenous Canadian to be honored this way.

- Since 1967: Several elementary schools were named after her in British Columbia and Ontario. A high school in Brantford, Ontario, is also named Pauline Johnson Collegiate & Vocational School.

- 2004: An Ontario Historical Plaque was placed at Chiefswood to remember Johnson's importance.

- 2010: Canadian actor Donald Sutherland read a quote from her poem "Autumn's Orchestra" at the opening of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

- 2014: The City Opera of Vancouver created an opera called Pauline, about her life and identity. The music was by Tobin Stokes, and the story was written by Margaret Atwood.

- 2016: Johnson was one of five women considered to be featured on Canadian banknotes. Viola Desmond was chosen.

See also

In Spanish: Pauline Johnson para niños

In Spanish: Pauline Johnson para niños

- Canadian literature

- Canadian poetry

- List of Canadian poets

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |