Ernest Lawrence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernest Lawrence

|

|

|---|---|

Lawrence in 1939

|

|

| Born |

Ernest Orlando Lawrence

August 8, 1901 Canton, South Dakota, U.S.

|

| Died | August 27, 1958 (aged 57) Palo Alto, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Mary K. Blumer

(m. 1932) |

| Children | 2 sons, 4 daughters |

| Relatives | John H. Lawrence (brother) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The Photoelectric Effect in Potassium Vapor as a Function of the Frequency of the Light (1924) |

| Doctoral advisor | William Francis Gray Swann |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (born August 8, 1901 – died August 27, 1958) was an American physicist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939. This award was for his amazing invention, the cyclotron. The cyclotron is a machine that speeds up tiny particles.

Lawrence also worked on separating different types of uranium. This was important for the Manhattan Project during World War II. He also started two famous science labs. These are the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Lawrence studied at the University of South Dakota and the University of Minnesota. He earned his PhD in physics from Yale University in 1925. In 1928, he became a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He was the youngest full professor there at just 29 years old.

One evening, he saw a diagram of a particle accelerator. He wondered how to make it smaller. This led him to invent the cyclotron. It was a circular machine that used magnets to speed up particles.

Lawrence built bigger and better cyclotrons over time. His lab became a special department at the University of California. He also supported using cyclotrons for medical research. During World War II, he developed a way to separate uranium using machines called calutrons. These were like a mix of a mass spectrometer and a cyclotron. A huge factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee to use this method.

After the war, Lawrence pushed for more government funding for science. He believed in "Big Science", which needed large machines and lots of money. He also supported creating a second nuclear weapons lab. This lab was built in Livermore, California. After he passed away, the labs he founded were named after him. Even a chemical element, lawrencium, was named in his honor.

Contents

Ernest Lawrence's Early Life

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was born in Canton, South Dakota. This happened on August 8, 1901. His parents, Carl and Gunda Lawrence, were children of Norwegian immigrants. They both taught at the high school in Canton. His father was also the school superintendent.

Ernest had a younger brother, John H. Lawrence. John became a doctor and was a pioneer in nuclear medicine. Ernest's best friend growing up was Merle Tuve. Merle also became a very successful physicist.

Lawrence went to public schools in Canton and Pierre. He then attended St. Olaf College. After a year, he moved to the University of South Dakota. He finished his bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1922. He earned his master's degree in physics in 1923. This was from the University of Minnesota.

Lawrence then followed his professor, William Francis Gray Swann, to Yale University. He earned his PhD in physics from Yale in 1925. His doctoral paper was about the photoelectric effect. This is how light can make electrons move. He stayed at Yale as a researcher.

With Jesse Beams, Lawrence continued studying the photoelectric effect. They showed that electrons appeared very quickly after light hit a surface. This was within 2 billionths of a second.

Starting His Career

In 1926 and 1927, Lawrence received job offers. These were from the University of Washington and the University of California. Yale offered him a similar job but for less money. Lawrence chose to stay at Yale because it was more famous.

In 1928, Lawrence became an associate professor at the University of California. Two years later, he became the youngest full professor there. He met important people through a club called the Bohemian Club. These people helped him get money for his research. They hoped his work on particle physics would lead to new medical uses. This helped fund his early discoveries.

While at Yale, Lawrence met Mary Kimberly Blumer, also known as Molly. They got married on May 14, 1932. They had six children: Eric, Margaret, Mary, Robert, Barbara, and Susan. Lawrence named his son Robert after his close friend, J. Robert Oppenheimer. In 1941, Molly's sister married Edwin McMillan. Edwin later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Inventing the Cyclotron

How the Cyclotron Was Born

The invention that made Lawrence famous started as a drawing on a napkin. In 1929, Lawrence was in the library. He saw an article by Rolf Widerøe. A diagram in the article showed a device that made high-energy particles. It used small "pushes" in a straight line.

At that time, scientists were starting to study the atomic nucleus. They wanted to break it apart. But nuclei have a positive charge. This charge pushes away other positive particles. To break them, much higher energy was needed.

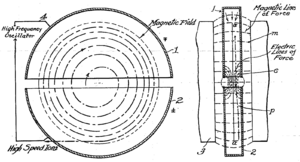

Lawrence realized that a straight accelerator would be too long. It wouldn't fit in his lab. So, he thought about making it circular. He decided to put a circular chamber between the poles of a magnet. The magnet would make charged particles move in a spiral path. They would get small pushes as they went around. After many turns, the particles would hit a target. They would be very high-energy particles. Lawrence was excited. He told his friends he could get high-energy particles without needing huge voltages.

His first cyclotron was very simple. It was made of brass, wire, and sealing wax. It was only about 10 centimeters (4 inches) wide. You could hold it in one hand. It probably cost only about $25 to build.

Lawrence needed smart students to help him. He worked with David H. Sloan and M. Stanley Livingston. Sloan worked on a straight accelerator. Livingston worked on the cyclotron. Both designs worked well. By May 1931, Sloan's machine could speed up particles to 1 million electron volts (MeV). Livingston had a harder job. But on January 2, 1931, his 28-centimeter (11-inch) cyclotron worked. It made protons spin around at 80,000 electron volts. A week later, he reached 1.22 MeV. This was more than enough for his PhD project.

Making It Better

As soon as one cyclotron worked, Lawrence started planning a bigger one. He and Livingston designed a 69-centimeter (27-inch) cyclotron in 1932. The magnet for the smaller 11-inch cyclotron weighed 2 tons. But Lawrence found a huge 80-ton magnet in a junkyard. It was from World War I and was perfect for the 27-inch cyclotron.

The cyclotron was a powerful tool. But it didn't immediately lead to new scientific discoveries. In April 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton in England announced something big. They had hit lithium with protons. They changed it into helium. The energy needed was low enough for Lawrence's 11-inch cyclotron. Lawrence's team confirmed their results in September.

Lawrence's lab, the Radiation Laboratory, focused on building bigger machines. This helped other scientists make important discoveries in high energy physics. He built the world's leading lab for nuclear physics in the 1930s. He received a patent for the cyclotron in 1934.

In 1936, Lawrence received job offers from Harvard. The University of California responded by making his lab better. The Radiation Laboratory became an official department. Lawrence was its director. The university agreed to give $20,000 a year for research. Lawrence hired many graduate students and young scientists.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

The Radiation Lab's War Work

When World War II started in Europe, Lawrence began working on military projects. He helped find scientists for the MIT Radiation Laboratory. This lab developed the cavity magnetron, a key part of radar. He also helped with research to find German submarines.

Meanwhile, work continued on cyclotrons in Berkeley. In December 1940, Glenn T. Seaborg and Emilio Segrè used a 152-centimeter (60-inch) cyclotron. They bombarded uranium-238 with deuterons. This created a new element, neptunium-238. It then changed into plutonium-238. One type of plutonium, plutonium-239, could split apart. This meant it could be used to make an atomic bomb.

In September 1941, a British scientist named Oliphant met Lawrence and Oppenheimer. He urged them to work on developing an atomic bomb. Lawrence had already thought about separating uranium-235 from uranium-238. This process is called uranium enrichment. It was hard because the two types of uranium are very similar.

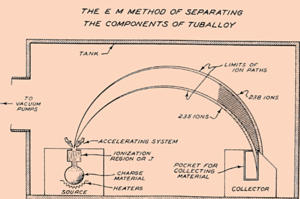

Lawrence started changing his old 94-centimeter (37-inch) cyclotron. He turned it into a giant mass spectrometer. This new machine was called a calutron. The name came from "California university cyclotrons." In November 1943, 29 British scientists joined Lawrence's team in Berkeley.

The electromagnetic method used a magnetic field. This field bent charged particles based on their weight. This process was not very efficient. It used a lot of materials and workers. But it was chosen because it was based on proven technology. It could also be built in stages.

Building Y-12 at Oak Ridge

A huge factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It was called Y-12. This factory would use Lawrence's calutrons to separate uranium. The calutrons were made by Allis-Chalmers. They used 14,700 tons of silver.

When the plant started testing in October 1943, there were problems. The large vacuum tanks moved out of place. The magnetic coils also shorted out. Rust was found inside the magnets. The plant had to be taken apart and cleaned.

Tennessee Eastman managed the Y-12 plant. Y-12 first enriched uranium-235 to 13% to 15%. The first few hundred grams were sent to the Los Alamos laboratory in March 1944. Only a tiny part of the uranium feed became the final product. The rest was spread over the equipment. Workers tried hard to recover the lost uranium. By January 1945, they recovered 10% of the uranium-235.

On July 16, 1945, Lawrence watched the first atomic bomb test. It was called the Trinity nuclear test. He was very excited when it worked. Scientists then discussed how to use the bomb on Japan. Lawrence believed a demonstration of its power would be wise. When a uranium bomb was used on Hiroshima without warning, Lawrence felt proud of his work.

After the war, the calutrons were found to be too expensive. The Y-12 plant was closed in December 1945. The number of staff at the Radiation Laboratory also dropped a lot.

After the War

Big Science and New Machines

After the war, Lawrence strongly supported government funding for science. He believed in "Big Science." This meant needing huge machines and lots of money. In 1946, he asked for over $2 million for his lab. The money was approved.

The 4.7-meter (184-inch) cyclotron was finished with wartime money. It used new ideas and became a synchrocyclotron. It started working on November 13, 1946. Lawrence actively joined the experiments again. He worked with Eugene Gardner to try and create pi mesons.

In 1947, the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) took over the national labs. Lawrence asked for $15 million for his projects. This included a new linear accelerator and a new giant synchrotron. This new machine became known as the bevatron.

Lawrence was a Republican. He did not like it when J. Robert Oppenheimer tried to form a union at the lab before the war. Lawrence thought political activities wasted time that should be spent on science. He wanted to keep politics out of the Radiation Laboratory.

In the time after the war, there was a lot of tension. Lawrence accepted the actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee. He did not see them as a problem for academic freedom. He tried to protect his staff members who were investigated. But he stopped Robert Oppenheimer's brother, Frank, from working at the lab. This hurt his friendship with Robert.

Working on Thermonuclear Weapons

Lawrence was worried when the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear bomb in August 1949. He believed the U.S. needed to build a bigger nuclear weapon: the hydrogen bomb. He suggested using accelerators to make the materials needed for the bomb.

Lawrence strongly supported Edward Teller's idea for a second nuclear weapons lab. Lawrence suggested building it in Livermore, California. The new lab at Livermore was approved on July 17, 1952.

Death and Lasting Impact

Besides the Nobel Prize, Lawrence received many other awards. These included the Elliott Cresson Medal and the Hughes Medal in 1937. He also received the Medal for Merit in 1946. In 1957, he received the Enrico Fermi Award. He was also made an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1948.

In July 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Lawrence to go to Geneva, Switzerland. He was to help discuss a treaty to ban nuclear tests. Lawrence was known to support continued nuclear testing. Even though he was very sick, Lawrence decided to go. He became ill in Geneva and was rushed to the hospital. He died in Palo Alto, California on August 27, 1958. He was 57 years old.

Just 23 days after his death, the Regents of the University of California renamed two of their nuclear research sites after him. These were the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award was created in his memory in 1959. Chemical element number 103, discovered in 1961, was named lawrencium after him. In 1968, the Lawrence Hall of Science was opened to teach the public about science.

In the 1980s, Lawrence's wife, Molly, asked the university to remove his name from the Livermore Laboratory. This was because it focused on nuclear weapons. But her request was denied each time. She lived for over 44 years after her husband. She passed away in 2003 at age 92.

See also

In Spanish: Ernest Lawrence para niños

In Spanish: Ernest Lawrence para niños