Exhumation and reburial of Richard III of England facts for kids

The story of finding and reburying King Richard III began when his bones were found in September 2012. They were discovered under a car park in Leicester, England. This car park was once the site of the Greyfriars Friary Church. After many tests on the bones, including DNA, the remains of Richard III were finally reburied. This happened at Leicester Cathedral on March 26, 2015. Richard III was the last English king to die in battle.

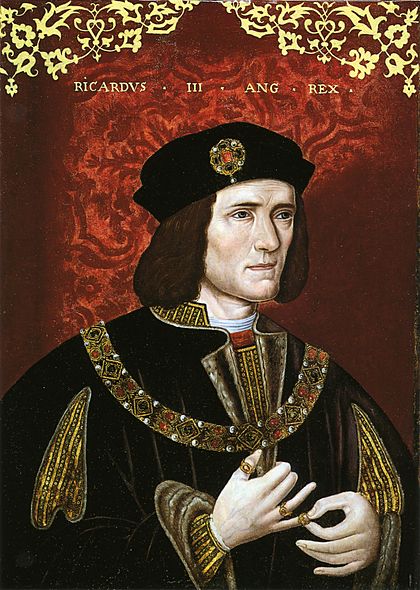

Richard III was the last king from the Plantagenet family. He was killed on August 22, 1485, during the Battle of Bosworth Field. This was the last big battle of the Wars of the Roses. His body was taken to Greyfriars Friary in Leicester. There, he was buried quickly in a simple grave inside the church.

Later, in 1538, the friary was closed down and pulled apart. Richard's grave was then lost. A wrong story started that his bones had been thrown into the River Soar near Bow Bridge.

A search for Richard's body started in August 2012. It was part of the Looking for Richard project. The Richard III Society supported this project. The archaeological excavation was led by the University of Leicester Archaeological Services. They worked with Leicester City Council. On the very first day, they found a human skeleton. It belonged to a man in his thirties and showed signs of serious injuries. The skeleton had some unusual features, especially a severely curved back, called scoliosis. The bones were dug up so scientists could study them.

The age of the bones matched Richard's age when he died. The bones were also from around the time of his death. Their features matched old descriptions of the king. Early DNA tests showed that DNA from the bones matched two of Richard's living relatives. These relatives were from his sister Anne of York's family line.

Considering all this evidence, the University of Leicester announced on February 4, 2013, that the skeleton was definitely Richard III.

The archaeologists had agreed to rebury Richard's remains in Leicester Cathedral if they found him. This was a condition for being allowed to dig up the skeleton. But then, a debate started. Some people thought York Minster or Westminster Abbey would be better places for him to be reburied. A court case confirmed that judges could not decide this matter. So, Richard was reburied in Leicester on March 26, 2015. The ceremony was shown on TV. The Archbishop of Canterbury and other Christian leaders were there.

Contents

Richard's Death and First Burial

Richard III died fighting Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. This was the last big battle of the Wars of the Roses. A Welsh poet named Guto'r Glyn said that Sir Rhys ap Thomas, a Welsh soldier in Henry's army, killed Richard. After he died, Richard's body was stripped and taken to Leicester. It was put on public display.

An old poem says his body was "in Newarke laid." This likely means the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke. This church was on the edge of Leicester. According to a writer named Polydore Vergil, Henry VII stayed in Leicester for two days. On August 25, 1485, Richard's body was buried at the "convent of Franciscan monks" in Leicester. There was no fancy funeral. Another writer, John Rous, wrote that Richard was buried "in the choir of the Friars Minor at Leicester." Modern experts believe these accounts are the most accurate.

Where Was He Buried?

In 1495, ten years after Richard's burial, Henry VII paid for a special tomb. It was made of marble and alabaster. Records show that two men were paid to make and move the tomb from Nottingham to Leicester. No one wrote down exactly what the tomb looked like. But Raphael Holinshed wrote in 1577 that it had "a picture of alabaster representing [Richard's] person." Later, Sir George Buck said it was "a fair tomb of mingled colour marble adorned with his image." Buck also wrote down the words carved on the tomb.

After the friary was closed in 1538, Greyfriars was torn down. Richard's tomb was either destroyed or slowly fell apart. The land where the friary stood was sold. Later, Robert Herrick, the Mayor of Leicester, bought it. He built a large house near Friary Lane and turned the rest of the land into gardens. Even though Richard's tomb was gone, people still knew where his grave was.

An old writer, Christopher Wren (father of the famous architect), wrote that Herrick put up a stone pillar. It was three feet tall and marked the grave. It said, "Here lies the Body of Richard III, Some Time King of England." This pillar was seen in 1612 but was gone by 1844.

A mapmaker and historian named John Speed wrote in 1611 that people in Leicester believed Richard's body had been thrown into the River Soar. This was said to have happened near Bow Bridge. Many writers later believed this story. In 1856, a plaque was put up near Bow Bridge. It said, "Near this spot lie the remains of Richard III." In 1862, a skeleton was found in the river near the bridge. Some thought it was Richard's, but it turned out to be a younger man's bones.

It's not clear where Speed's story came from. It had no earlier sources. Writer Audrey Strange thinks it might be a confused version of what happened to John Wycliffe's remains in 1428. A mob dug up Wycliffe, burned his bones, and threw them into a river. Historian John Ashdown-Hill thinks Speed made a mistake about the grave's location. He might have invented the river story to explain why the grave was missing. Speed's map of Leicester was also wrong about where Greyfriars was. This suggests he looked for the grave in the wrong place.

Another local story was about a stone coffin. People said it held Richard's remains. Speed wrote that it was "now made a drinking trough for horses at a common Inn." A coffin did exist. John Evelyn saw it in 1654. Celia Fiennes wrote in 1700 that she saw "a piece of his tombstone [sic] he lay in." It was at the Greyhound Inn in Leicester. William Hutton found in 1758 that the coffin was at the White Horse Inn. The coffin's location is now unknown. But its description does not match coffins from the late 1400s. It was probably not connected to Richard. It was more likely saved from another religious building that was torn down.

Herrick's house, Greyfriars House, stayed in his family until 1711. The property was later divided and sold in 1740. Three years later, New Street was built across part of the site. Many burials were found when houses were built along this street. A house, 17 Friar Lane, was built on the eastern part of the site in 1759. It is still there today.

During the 1800s, more buildings were put up on the site. In 1863, Alderman Newton's School built a schoolhouse there. Herrick's house was torn down in 1871. Grey Friars Street was built through the site in 1873. More businesses were built, including a bank. In 1915, Leicestershire County Council bought the rest of the site. They built offices there in the 1920s and 1930s. The council moved in 1965. Leicester City Council then moved into the old offices. The rest of the site, where Herrick's garden had been, became a staff car park around 1944. No other buildings were put there.

In 2007, a building from the 1950s was torn down on Grey Friars Street. This gave archaeologists a chance to dig. They hoped to find parts of the medieval friary. Very little was found, except for a piece of a stone coffin lid. The dig suggested that the friary church was further west than people thought.

The Looking for Richard Project

Members of the Richard III Society had long been interested in finding Richard III's body. This group wanted to improve the king's reputation. In 1975, an article by Audrey Strange suggested his remains were under Leicester City Council's car park. In 1986, historian David Baldwin also thought the remains were still in the Greyfriars area. He wondered if an excavator might find the king's bones in the future.

The Richard III Society was interested but did not search for the bones themselves. People thought the grave site had been built over or the skeleton was scattered. This was because of John Speed's old story.

In 2004 and 2005, Philippa Langley, from the Richard III Society, did research in Leicester. She became sure that the car park was the key place to look. In 2005, John Ashdown-Hill announced he had found Richard III's mitochondrial DNA sequence. He did this by finding two living relatives of Richard's sister, Anne of York. He also believed the friary church ruins were under the car park. Langley asked Ashdown-Hill to contact the TV show Time Team. But they said no, as the dig would take too long.

Three years later, writer Annette Carson also concluded Richard's body was likely under the car park. She joined Langley and Ashdown-Hill. Langley then found a "smoking gun"—a medieval map of Leicester. It showed the Greyfriars Church at the north end of what was now the car park.

In February 2009, Langley, Carson, and Ashdown-Hill teamed up with Richard III Society members David and Wendy Johnson. They started a project called Looking for Richard: In Search of a King. Their goal was to find Richard's grave. They also wanted to tell his true story. They hoped to find his remains and rebury them with "honour, dignity and respect." To get support in Leicester, Langley got Darlow Smith Productions interested in making a TV documentary.

The project got support from several groups. These included Leicester City Council, Leicester Promotions (for tourism), the University of Leicester, Leicester Cathedral, Darlow Smithson Productions, and the Richard III Society. Money for the first research came from the Richard III Society. Leicester Promotions agreed to pay £35,000 for the dig. The University of Leicester Archaeological Services was chosen to do the archaeological work.

Greyfriars Project and Digs

In March 2011, experts started looking at the Greyfriars site. They wanted to find where the monastery had stood. They also wanted to see which land could be dug up. They studied old records to see if digging there would be useful. Then, in August 2011, they used ground-penetrating radar (GPR). The GPR results were not clear. They could not find any clear building remains. This was because of a layer of disturbed ground and old building rubbish. But the survey did help find modern pipes and cables.

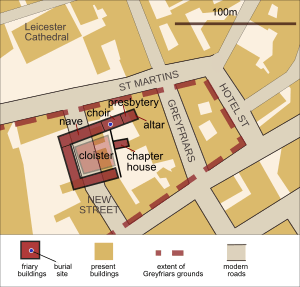

Three possible dig sites were found. These were the staff car park of Leicester City Council, the old playground of Alderman Newton's School, and a public car park on New Street. They decided to dig two trenches in the Social Services car park. There was an option for a third trench in the playground. Most of the Greyfriars site had buildings on it. So, only 17% of its old area was available to dig. The project's money limits meant they could only dig 1% of the site.

The planned dig was announced in June 2012. But a month later, one main sponsor pulled out. This left a £10,000 money gap. An appeal led to members of Richard III groups donating £13,000 in two weeks. A press conference was held in Leicester on August 24. Archaeologist Richard Buckley said finding the king was a long shot. "We don't know exactly where the church is, let alone where the burial site is," he said. He had told Langley earlier that the chances of finding the church were "fifty-fifty at best," and finding the grave was "nine-to-one against."

Digging started the next day. They dug a trench about 1.6 meters (5.2 feet) wide and 30 meters (98 feet) long. It ran north to south. First, they removed a layer of modern building rubbish. Then they reached the level of the old monastery. Two parallel human leg bones were found about 5 meters (16 feet) from the north end of the trench. They were about 1.5 meters (5 feet) deep. This showed an undisturbed burial. The bones were covered to protect them while digging continued. A second trench was dug the next day.

Over the next few days, they found medieval walls and rooms. This helped archaeologists find the friary's area. It became clear that the bones found on the first day were inside the east part of the church. This was likely the choir, where Richard was said to be buried. On August 31, the University of Leicester asked the Ministry of Justice for permission. They wanted to dig up up to six human skeletons. To narrow the search, they planned to only dig up men in their thirties who were buried inside the church.

The bones found on August 25 were uncovered on September 4. The grave soil was dug back more over the next two days. The feet were missing. The skull was found in an unusual propped-up position. This meant the body was put into a grave that was a bit too small. The spine was curved in an S-shape. No coffin was found. The skeleton's position suggested the body was not put in a shroud. It looked like it had been quickly dumped into the grave. As the bones were lifted, a piece of rusted iron was found under the spine. The skeleton's hands were in an unusual position, crossed over the right hip. This might mean they were tied together when he was buried, but this was not certain. After the bones were dug up, work continued for another week. Then the site was covered with soil. The car park and playground were put back to how they were before.

Identifying Richard III and Other Discoveries

On February 4, 2013, the University of Leicester confirmed the skeleton was Richard III. This was based on mitochondrial DNA evidence, soil tests, and dental checks. The skeleton's features also matched old descriptions of Richard. Osteoarchaeologist Jo Appleby said: "The skeleton has unusual features: its slender build, the scoliosis, and injuries from battle. All these match what we know about Richard III's life and how he died."

Caroline Wilkinson, a professor from the University of Dundee, led the project to rebuild Richard's face. This was asked for by the Richard III Society. On February 11, 2014, the University of Leicester announced a project led by Turi King. They would sequence the full DNA of Richard III. They also sequenced the DNA of Michael Ibsen. He is a direct female-line descendant of Richard's sister, Anne of York. His DNA confirmed the skeleton's identity. Richard III is the first ancient person with a known historical identity whose full DNA has been sequenced.

A study published in December 2014 confirmed a perfect DNA match between Richard's skeleton and Michael Ibsen. It also showed a very close match between Richard and another living relative. However, Y chromosome DNA, passed down through the male line, did not link Richard to five other claimed male relatives. This means that at least one "false-paternity event" (a child not being the biological son of the supposed father) happened in the generations between Richard and these men. One of these five men was not related to the other four. This showed another false-paternity event had happened.

The story of the dig and the science was told in a Channel 4 TV show. It was called Richard III: The King in the Car Park. It was shown on February 4, 2013. It was very popular, watched by up to 4.9 million people. It won a TV award. Channel 4 later showed another documentary on February 27, 2014. It was called Richard III: The Untold Story. This show explained the science that identified the skeleton.

The site was dug up again in July 2013. This was to learn more about the friary church before building work started nearby. Leicester City Council and the University of Leicester paid for this. They dug a single trench, about twice the size of the 2012 trenches. This dig showed the full sites of the Greyfriars presbytery and choir. This confirmed what archaeologists thought about the church's layout. Three burials found in 2012 but not dug up were looked at again. One burial was in a wooden coffin in a well-dug grave. A second wooden-coffined burial was found under the choir and presbytery. Its position suggests it was there before the church was built.

A stone coffin found in 2012 was opened for the first time. Inside, there was a lead coffin. An endoscope was used to look inside. It showed a skeleton, some hair, and pieces of a shroud and cord. At first, they thought the skeleton was a man, maybe a knight named Sir William de Moton. But later tests showed it was a woman. She was likely an important lady who helped the church. She might not have been from Leicester, as lead coffins were used to move bodies over long distances.

Reburial Plans and Challenges

The University of Leicester planned to bury Richard's body in Leicester Cathedral. This followed British law. It says that Christian burials found by archaeologists should be reburied in the closest holy ground to the original grave. This was also a condition of the license from the Ministry of Justice to dig up any human remains. The Royal Family did not claim the remains. Queen Elizabeth II was asked but said no to a royal burial. So, the Ministry of Justice first said the University of Leicester would decide where the bones should go. David Monteith, from Leicester Cathedral, said Richard's skeleton would be reburied in early 2014. It would be a "Christian-led but ecumenical service." This means it would include different Christian groups. It would be a service of remembrance, not a new funeral.

The choice of burial site caused a lot of debate. Some people suggested other places for Richard to be buried. They felt these places were better for a Roman Catholic and Yorkist king. Online petitions asked for Richard to be buried in Westminster Abbey. This is where 17 other English kings are buried. Others wanted him in York Minster. They said Richard himself wanted to be buried there. Some suggested the Roman Catholic Arundel Cathedral or even back in the Leicester car park. Only Leicester and York got a lot of public support. Leicester got 3,100 more signatures than York.

The issue was even talked about in the Houses of Parliament. A politician named Chris Skidmore suggested a state funeral. Another politician, John Mann, suggested burying the body in Worksop. This town is halfway between York and Leicester. All these ideas were rejected in Leicester. The mayor, Peter Soulsby, said: "Those bones leave Leicester over my dead body."

A group called the "Plantagenet Alliance" took legal action. This group said they were descendants of Richard. His final resting place was uncertain for almost a year. The group said they were "his Majesty's representatives and voice." They wanted Richard buried in York Minster, which they claimed was his "wish." The Dean of Leicester called their challenge "disrespectful." He said the cathedral would not spend more money until the matter was decided. Historians said there was no proof that Richard III wanted to be buried in York. Mark Ormrod from the University of York doubted Richard had made clear plans for his own burial. The Plantagenet Alliance's right to challenge was questioned. A mathematician named Rob Eastaway calculated that Richard III might have millions of living relatives. He said, "we should all have the chance to vote on Leicester versus York."

In August 2013, Justice Haddon-Cave allowed a court review. He said the original burial plans did not follow the common law duty "to consult widely as to how and where Richard III's remains should appropriately be reinterred." The court review started on March 13, 2014. It was expected to last two days. But the decision was put off for four to six weeks. Lady Justice Hallett and two other judges said they needed time to think about their decision. On May 23, the High Court ruled there was "no duty to consult." They said there were "no public law grounds for the court to interfere." So, the reburial in Leicester could go ahead. The legal case cost the defendants £245,000. This was much more than the original dig.

Reburial and Celebrations

In February 2013, Leicester Cathedral announced when and how Richard's remains would be reburied. The cathedral planned to bury him in a "place of honour" inside the cathedral. Early ideas for a flat stone were not popular. A table tomb was the most popular choice. This was among members of the Richard III Society and in polls of Leicester people. In June 2014, the design was announced. It would be a table tomb made of Swaledale fossil stone on a Kilkenny marble base. That month, the statue of Richard III from Leicester's Castle Gardens was moved. It went to the new Cathedral Gardens, which opened on July 5, 2014.

The reburial happened during a week of events from March 22 to 27, 2015. Here's what happened:

- Sunday, March 22, 2015: Richard's bones were sealed in a lead-lined box. This box was put into a wooden coffin. The remains were moved from the University of Leicester to Leicester Cathedral. The journey went through the Battle of Bosworth site, Dadlington, Sutton Cheney, and Market Bosworth. This followed part of Richard's last journey. The coffin was made from English oak by Michael Ibsen. It was moved from a car to a four-horse-drawn carriage to enter Leicester city.

- Monday, March 23 – Wednesday, March 25, 2015: The remains lay in the cathedral for people to see. People waited over four hours to view the coffin.

- Monday, March 23, 2015: Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the Archbishop of Westminster, held a Mass for Richard III's soul. This was at Holy Cross Priory, Leicester, the Catholic church.

- Thursday, March 26, 2015: The reburial took place. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, and other Christian leaders were there. The service was shown live on Channel 4. It included prayers for Richard III and for those who died at Bosworth and other wars. Actor Benedict Cumberbatch, a distant relative of Richard III, read a poem. The poem was written for the service by the poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy. The Royal Family was represented by Sophie, Countess of Wessex, Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and his wife Birgitte, Duchess of Gloucester. Richard III was Duke of Gloucester before he became king. Music during the service included old songs and new pieces.

- Friday, March 27, 2015: The tomb was shown to the public. This was at a Service of Reveal at Leicester Cathedral. Other events happened across Leicester.

What Happened Next

After the discovery, Leicester City Council set up a temporary exhibit about Richard III. It was in the city's old guildhall. The council then announced they would create a permanent attraction. They spent £850,000 to buy St Martin's Place. This site is across the road from the cathedral. It is next to the car park where the body was found. It is also over the choir of Greyfriars Friary Church. This site was turned into the £4.5 million King Richard III Visitor Centre. It tells the story of Richard's life, death, burial, and rediscovery. It has items from the dig, like Philippa Langley's boots. Visitors can see the grave site under a glass floor. The council thought the visitor centre, which opened in July 2014, would attract 100,000 visitors each year.

In Norway, archaeologist Øystein Ekroll hoped that the interest in finding the English king would help Norway. In England, almost all graves of kings since the 1000s have been found. But in Norway, about 25 medieval kings are buried in unmarked graves. Ekroll suggested starting with Harald Hardrada. He was likely buried without a marker in Trondheim, under what is now a public road. An earlier attempt to dig up Harald in 2006 was stopped.

Richard Buckley, from the University of Leicester, had joked he would "eat his hat" if Richard was found. He kept his promise by eating a hat-shaped cake. Buckley later said: "Cutting-edge research has been used in the project. The discoveries, like the very exact carbon dating and medical evidence, will be a guide for other studies. And it is, of course, an amazing story. He's a controversial figure; people love the idea he was found under a car park; the whole thing unfolded in the most amazing way. You couldn't make it up."

Some people thought the discovery and the good feeling it brought to Leicester helped Leicester City F.C. win the Premier League in 2016. A few days after the burial, Leicester City started winning games. They went from last place to safely avoiding being moved down a league. They then won the league the next year. Mayor Peter Soulsby said: "For too long, people in Leicester have been modest about their achievements and the city they live in. Now – thanks first to the discovery of King Richard III and the Foxes' amazing season – it's our time to step into the international limelight."

These two events inspired Michael Morpurgo's 2016 children's book, The Fox and the Ghost King. In the book, the ghost of Richard III promises to help the football team. This is in return for being released from his car park grave.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Funeral de Ricardo III de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Funeral de Ricardo III de Inglaterra para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |