Faith Ringgold facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Faith Ringgold

|

|

|---|---|

Ringgold in 2017

|

|

| Born |

Faith Willi Jones

October 8, 1930 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | April 13, 2024 (aged 93) Englewood, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Education | City College of New York |

| Known for | Painting Textile arts Children's Books |

|

Notable work

|

The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding (1967) The American People Series #20: Die (1967) Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) Tar Beach (1991) The French Collection (1991–1997) The American Collection (1997) |

| Movement | Feminist art movement, Civil rights |

| Awards | 2009 Peace Corps Award |

Faith Ringgold (born Faith Willi Jones; October 8, 1930 – April 13, 2024) was an American artist. She was famous for her paintings, sculptures, and especially her story quilts. Faith Ringgold's art often shared important stories about American history, civil rights, and women's experiences. She used many different materials, like fabric, to create her unique artworks.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Faith Willi Jones was born on October 8, 1930, in Harlem Hospital in New York City. She was the youngest of three children. Her parents, Andrew Louis Jones and Willi Posey Jones, came from working-class families who moved north during the Great Migration. This was a time when many African Americans moved from the Southern United States to the North.

Faith's mother was a fashion designer, and her father was a great storyteller. They encouraged her creativity from a young age. Growing up in Harlem, she was surrounded by a lively arts scene. Famous people like Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes lived nearby. Her childhood friend, Sonny Rollins, who became a famous jazz musician, often practiced saxophone at her family's parties.

Faith had chronic asthma, so she spent a lot of time exploring art. Her mother taught her how to sew and work with fabric. Even though she grew up during the Great Depression, Faith felt protected and loved by her family. Her art was influenced by the people, poetry, and music around her. It also showed her experiences with racism, sexism, and segregation.

In 1948, Faith started college at the City College of New York. She wanted to study art, but at that time, women could only enroll in certain majors. So, she studied art education instead. In 1950, she married Robert Earl Wallace and had two daughters, Michele and Barbara Faith Wallace. She later separated from Wallace. During this time, she learned from artists like Robert Gwathmey and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. She also met printmaker Robert Blackburn, and they worked together on prints years later.

Faith earned her bachelor's degree in 1955 and started teaching in New York City public schools. In 1959, she received her master's degree. She then traveled to Europe with her mother and daughters. Visiting museums like the Louvre in Paris inspired her later quilt series, The French Collection. Her trip ended early when her brother passed away in 1961. Faith married Burdette Ringgold in 1962.

She also visited West Africa twice in the 1970s. These trips greatly influenced her art, especially her masks, doll paintings, and sculptures.

Faith Ringgold's Artworks

Faith Ringgold's art includes many different forms, from paintings and quilts to sculptures and performance art. She also wrote and illustrated children's books. In 1973, she stopped teaching public school to focus on creating art full-time.

Painting

Faith Ringgold started painting in the 1950s. Her early paintings used flat figures and shapes. She was inspired by writers like James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka, as well as African art, Impressionism, and Cubism. Many of her early works explored racism in everyday life. These paintings were often political and showed her experiences growing up during the Harlem Renaissance. These themes became even stronger during the Civil Rights Movement and the Women's movement.

In 1963, she created her first political art collection called the American People Series. This series showed American life during the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1972, Faith created For the Women's House for a women's prison on Rikers Island. This was her first public art project and is seen as her first feminist artwork. It also inspired the creation of Art Without Walls, an organization that brings art to prisons.

Faith also worked on her America Black collection, also called the Black Light Series, where she used darker colors. She considered painting her main way of expressing herself.

Quilts

Faith Ringgold started using fabric and making quilts to move away from traditional Western painting styles. Quilts also allowed her to support the feminist movement. She could easily roll up her quilts to take them to galleries, which meant she didn't need help from others to move her art.

She began writing stories on her quilts in 1983. This was a way for her stories to be seen and read, especially since her autobiography wasn't being published at the time. She said, "when my quilts were hung up to look at, or photographed for a book, people could still read my stories."

Her first story quilt, Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983), reimagined the character of Aunt Jemima as a strong businesswoman. Another quilt, Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986), explored a woman's journey to feel good about herself.

The story quilts from her The French Collection (1991–1997) focused on important African-American women who worked to change the world. Many of her quilts later inspired the children's books she wrote, like Dinner at Aunt Connie's House (1993), which was based on The Dinner Quilt (1988).

Faith followed The French Collection with The American Collection (1997), which continued the stories from the previous series.

Sculpture

In 1973, Faith Ringgold started making sculptures to capture stories from her community and national events. Her sculptures included costumed masks, hanging soft sculptures, and freestanding figures. These represented both real and imaginary people from her life.

She made a series of eleven mask costumes called the Witch Mask Series with her mother. These costumes could actually be worn. After that, she created the Family of Woman Mask Series, which included 31 masks honoring women and children she knew.

She then started making dolls with painted gourd heads and costumes, also made by her mother. These led to life-sized soft sculptures. One of her first was Wilt, a 7-foot-3-inch tall sculpture of basketball player Wilt Chamberlain. Her soft sculptures later became "portrait masks" of people from her life and society, from people in Harlem to Martin Luther King Jr..

Performance Art

Since many of Faith Ringgold's mask sculptures could be worn, she naturally moved into performance art. She was inspired by African traditions that combine storytelling, dance, music, costumes, and masks.

Her first performance piece was The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro. This work was her response to the American Bicentennial celebrations in 1976. She felt that many African Americans had "no reason to celebrate two hundred years of American Independence" because of the history of slavery. The performance included mime, music, and many of her past artworks.

She created other performance pieces, including Being My Own Woman: An Autobiographical Masked Performance Piece and The Bitter Nest (1985), a masked story about the Harlem Renaissance. She also made Change: Faith Ringgold's Over 100 Pound Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986) to celebrate her weight loss. These performances used masks, costumes, quilts, paintings, storytelling, song, and dance. Faith often invited her audience to sing and dance with her. She explained that her performances were "simply another way to tell my story."

Children's Books

Faith Ringgold wrote and illustrated 17 children's books. Her first book, Tar Beach, was published in 1991 and was based on her quilt story of the same name. For Tar Beach, she won the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award and the Coretta Scott King Award for Illustration. She was also a runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, a top award for picture book illustration. In her books, Faith Ringgold talked about difficult topics like racism in clear and hopeful ways. She mixed fantasy and realism to create inspiring messages for children.

Her notable children's books include:

- Tar Beach (1991)

- Aunt Harriet's Underground Railroad in the Sky (1992)

- Dinner at Aunt Connie's House (1993)

- Bonjour, Lonnie (1996)

- My Dream of Martin Luther King (1996)

- The Invisible Princess (1998)

- If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks (1999)

- Cassie's Word Quilt (2002)

- Harlem Renaissance Party (2015)

- We Came to America (2016)

Activism

Faith Ringgold was an activist for much of her life. She was involved in several groups that fought for women's rights and against racism.

In 1968, she joined other artists like Poppy Johnson and Lucy Lippard to form the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists. They protested a big art show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The group demanded that women artists make up half of the artists shown. They protested by singing, blowing whistles, and leaving raw eggs and sanitary napkins at the museum. Not only were women artists left out of the show, but no African-American artists were included either. Even Jacob Lawrence, whose art was in the museum's collection, was not featured. Faith Ringgold was arrested on November 13, 1970, for her protest activities.

Faith Ringgold and Lucy Lippard also worked together in the group Women Artists in Revolution (WAR). Around the same time, Faith and her daughter Michele Wallace started Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL). Around 1974, Faith and Michele were also founding members of the National Black Feminist Organization.

Faith was also a founding member of "Where We At" Black Women Artists, a group of women artists in New York connected to the Black Arts Movement. Their first art show in 1971 featured "soul food" instead of traditional drinks, showing their connection to their cultural roots.

In 2004, Faith Ringgold spoke about the importance of Black representation in art. She said that when she was young, she saw paintings by Horace Pippin in her textbooks but didn't know he was Black. She explained that it's important for young people to see artists who look like them.

In 1988, Faith Ringgold co-founded the Coast-to-Coast National Women Artists of Color Projects with Clarissa Sligh. This organization showed the works of African American women across the United States.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1987, Faith Ringgold became a teacher in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego. She taught there until she retired in 2002.

In 1995, she published her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge. The book shared her life story as an artist, from her childhood in Harlem to her marriages, children, and career achievements. She received over 80 awards and honors, including 23 honorary doctorates.

Faith Ringgold lived with her second husband, Burdette "Birdie" Ringgold, in Englewood, New Jersey, where she had her art studio since 1992. Burdette passed away in 2020. Faith Ringgold died at her home in Englewood, New Jersey, on April 13, 2024, at the age of 93.

Selected Exhibitions

Faith Ringgold's first solo art show, American People, opened on December 19, 1967. It included three of her murals: The Flag is Bleeding, U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, and Die. She wanted the opening to be a "refined black art affair" with music and many guests.

In 2019, a large exhibition of Faith Ringgold's work was held at London's Serpentine Galleries. This was her first show at a European art institution. Her first career exhibition in her hometown opened at the New Museum, New York in 2022. It then traveled to the De Young Museum in San Francisco, the Musée Picasso in Paris, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in Chicago.

In 2020, her work was featured in Polyphonic: Celebrating PAMM's Fund for African American Art at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. She was also included in the 2022 exhibition Women Painting Women at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Images for kids

-

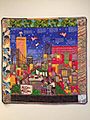

For the Women's House (1971) at the Brooklyn Museum in 2023

-

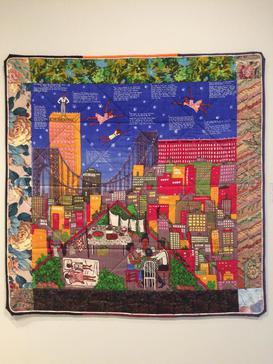

Tar Beach 2 (1990), by Ringgold. This painted story quilt tells the story of Cassie Louise Lightfoot, an 8-year-old girl who dreams of flying over her family's Harlem apartment building and throughout the rest of New York City. Photo taken at the Delaware Art Museum in 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Faith Ringgold para niños

In Spanish: Faith Ringgold para niños

- Feminist art movement in the United States

- Black feminism

- Harlem Renaissance

- Quilts

- Sculpture

- Painting

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |