Frank Slide facts for kids

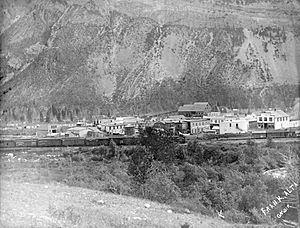

The town of Frank and Turtle Mountain on April 30, 1903, one day after the slide

|

|

| Date | April 29, 1903 |

|---|---|

| Time | 4:10 a.m. MST |

| Location | Frank, District of Alberta, Northwest Territories (now the province of Alberta), Canada |

| Coordinates | 49°35′28″N 114°23′43″W / 49.59111°N 114.39528°W |

| Deaths | 70–more than 90 |

The Frank Slide was a huge rockslide that covered part of the mining town of Frank, Canada. It happened at 4:10 AM on April 29, 1903. About 110 million tonnes of limestone rock slid down Turtle Mountain. People who saw it said the rocks moved incredibly fast. In just 100 seconds, they covered the eastern part of Frank, including the Canadian Pacific Railway tracks and the coal mine.

It was one of Canada's biggest and deadliest landslides. Between 70 and 90 people died, and most of them are still buried under the rocks. Many things caused the slide. Turtle Mountain was naturally unstable. Coal mining might have made it weaker. A wet winter and a sudden cold snap on the night of the slide also played a part.

The railway was fixed in three weeks, and the mine reopened quickly. In 1911, the part of town closest to the mountain was moved. People worried another slide might happen. The town's population grew after the slide but then shrank when the mine closed in 1917. Today, Frank is part of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass in Alberta. About 200 people live there. The slide area still looks much the same. It is now a popular place for tourists and has a special interpretive centre.

Contents

Frank Town's Early Days

The town of Frank was started in 1901. It was in the southwestern part of the Northwest Territories. A spot was chosen near Turtle Mountain in the Crowsnest Pass. Coal had been found there a year earlier. The town was named after Henry Frank, who owned the coal mine with Samuel Gebo.

They celebrated the town's opening on September 10, 1901. There were speeches, sports, dinner, and tours of the mine. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) brought over 1,400 people from nearby towns for the event. By April 1903, about 600 people lived in Frank. The town had a two-story school and four hotels.

About Turtle Mountain

Turtle Mountain is right south of Frank. It is made of an older layer of limestone folded over softer rocks like shale and sandstone. Over time, erosion made the limestone layer stick out steeply. The mountain has always been unstable. The Blackfoot and Kutenai peoples called it "the mountain that moves." They avoided camping near it.

In the weeks before the disaster, miners sometimes felt the mountain rumble. The shifting rocks even caused the wooden supports in the mine shafts to crack.

The Big Rockslide

Early on April 29, 1903, a freight train left the mine. As it slowly moved toward town, the crew heard a very loud rumble behind them. The engineer quickly sped the train to safety across a bridge. At 4:10 AM, 30 million cubic metres of limestone rock broke off Turtle Mountain. This huge amount of rock weighed 110 million tonnes.

The part that broke off was 1,000 metres wide, 425 metres high, and 150 metres deep. People who saw it said the slide took about 100 seconds to reach the hills on the other side. This means the rocks moved at about 112 kilometres per hour. The sound of the slide was heard as far away as Cochrane, over 200 kilometres north of Frank.

At first, news reports said Frank was "nearly wiped out." People thought an earthquake, volcano, or mine explosion caused it. Most of the town survived, but the slide buried buildings on the eastern edge of Frank. Seven cottages were destroyed, along with businesses, the cemetery, and two kilometres of road and railway tracks. All the mine's buildings were also covered.

About 100 people lived in the path of the slide. The exact number of deaths is not known, but it was between 70 and 90. This was Canada's deadliest landslide. It's possible more people died, as about 50 travelers were camped nearby looking for work. Most victims are still buried under the rocks. Only 12 bodies were found right away. Six more skeletons were found in 1924 when a new road was built.

Miners' Escape

News reports first said that 50 to 60 miners were trapped and had no hope. But only 20 miners were working that night. Three were outside the mine and died. The other 17 were underground. They found the mine entrance blocked. Water from the river, which was dammed by the slide, was coming in through another tunnel.

They tried to dig out but couldn't. One miner remembered a seam of coal that went to the surface. Working in small groups, they dug through the coal for hours. The air became harder to breathe. Only three men had enough energy to keep digging when they finally broke through to the surface late that afternoon. But it was too dangerous to leave because rocks were still falling.

Encouraged, the miners dug a new shaft. It came out under a rock that protected them from falling debris. Thirteen hours after being trapped, all 17 men came out of the mountain.

Stories of Survival

The miners found that their homes had been destroyed. Some of their families had died. One miner found his family safe in a makeshift hospital. But another found his wife and four children had died. Fifteen-year-old Lillian Clark was working late at the boarding house that night. She was allowed to stay overnight for the first time. She was the only one in her family to survive. Her father was working outside the mine, and her mother and six siblings were buried in their home.

All 12 men at the CPR work camp died. But 128 more men who were supposed to move into the camp the day before were saved. Their train from Morrissey, British Columbia didn't pick them up. The Spokane Flyer, a passenger train, was saved by CPR brakeman Sid Choquette. He and another man ran across the rocks to warn the train that the tracks were buried. Through falling rocks and dust, Choquette ran for two kilometres. The CPR gave him a letter of praise and $25 (about $750 today) for his bravery.

After the Slide

On April 30, a special train arrived from Fort Macleod with police and doctors. The Premier, Frederick Haultain, visited the site on May 1. Engineers told him there was little risk of another slide. But the CPR's chief engineer thought Frank was in danger. Haultain ordered the town to be evacuated.

Two geologists from the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) investigated. They said the slide created two new peaks on the mountain. They believed the north peak, overlooking the town, was not in danger of falling soon. So, the evacuation order was lifted on May 10, and people returned. The North-West Mounted Police kept order and made sure no one stole anything during the evacuation.

Clearing the Canadian Pacific Railway line was very important. About two kilometres of the main line were buried. The CPR cleared and rebuilt the line in three weeks. Workers also reopened paths to the old mine by May 30. They were amazed to find Charlie the horse, who had been trapped underground for over a month. He survived by eating wood and drinking water. Sadly, he died when his rescuers gave him too much oats and brandy.

The town's population grew after the slide. In 1906, it had 1,178 people. But a new study found that cracks in the mountain were still growing. The risk of another slide remained. So, parts of Frank closest to the mountain were moved to safer areas.

Why the Slide Happened

Several things caused the Frank Slide. A study by the GSC right after the slide said the main reason was the mountain's unstable shape. A layer of limestone sat on top of softer rocks. After years of erosion, this made a steep, top-heavy cliff. Cracks covered the eastern side of the mountain. Water flowed into the mountain's core through underground cracks.

Local Indigenous peoples, the Blackfoot and Ktunaxa, had old stories about the mountain moving. Miners noticed the mountain was becoming more unstable in the months before the slide. They felt small tremors. The mine superintendent reported a "general squeeze" deep inside the mountain. Coal was breaking off easily.

An unusually warm winter also played a part. Warm days and cold nights caused water in the mountain's cracks to freeze and thaw many times. This weakened the mountain. Heavy snow in March was followed by a warm April, which melted snow into the cracks. GSC geologists thought the weather that night likely triggered the slide. The train crew said it was the coldest night of the winter, below −18°C. Geologists believed the sudden cold snap caused the cracks to expand, making the limestone break off.

The GSC thought mining activities helped cause the slide, but the mine owners disagreed. Later studies suggested the mountain was very balanced. Even a small change, like the mine, could have helped trigger the slide. The mine reopened quickly, even though rocks kept falling. Coal production in Frank was highest in 1910. But the mine closed for good in 1917 because it was no longer making money.

The slide created two new peaks on the mountain. The south peak is 2,200 metres high, and the north peak is 2,100 metres high. Geologists believe another slide will happen someday, but not soon. The south peak is most likely to fall. It would probably be about one-sixth the size of the 1903 slide. The mountain is always watched for changes. Over 80 monitoring stations are on the mountain. They provide an early warning system for people living nearby.

Myths and Stories

Many myths and wrong ideas came out after the slide. Some people thought the whole town of Frank was buried, but most of it was fine. A story that a bank branch with $500,000 was buried lasted for many years. The bank was not touched by the slide. It stayed there until 1911, and then the "buried treasure" story started. In 1924, when crews built a new road, police guarded them because people thought they might find the buried bank.

Several people claimed to be the "sole survivor" of the slide. The most common story was about a baby girl named "Frankie Slide." People told amazing tales of her escape. She was found in a pile of hay, on rocks, under a collapsed roof, or in her dead mother's arms. This legend was mostly based on Marion Leitch's story. She was thrown from her home into a hay pile. Her sisters also survived unharmed. Her parents and four brothers died.

Another story that influenced the legend was about two-year-old Gladys Ennis. She was found outside her home in the mud. She was the last survivor of the slide and died in 1995. In total, 23 people in the slide's path survived, plus the 17 miners who escaped.

A song by Ed McCurdy about Frankie Slide was popular in Canada in the 1950s. The slide has also been the subject of other songs, like "How the Mountain Came Down" by Stompin' Tom Connors and "Frank, AB" by The Rural Alberta Advantage. The Frank Slide has also been written about in several books.

Lasting Impact

People came to see the slide site right after the disaster. It is still a popular place for tourists because it is close to the Crowsnest Highway (Highway 3). The province built a viewing area in 1941. In 1958, people tried to make it a National Historic Site, but it didn't happen. It was later named a Provincial Historic Site of Alberta.

In 1976, the government said the slide area could not be changed. A memorial plaque was put up in 1978. The Frank Slide Interpretive Centre opened in 1985. It is a museum and tourist stop that tells the story of the Frank Slide and the area's coal mining history. Over 100,000 tourists visit the centre every year.

Even though Frank recovered and its population reached 1,000, it slowly declined after the mine closed. Frank stopped being its own community in 1979. It joined with nearby towns like Blairmore, Coleman, Hillcrest, and Bellevue to form the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass. Today, Frank has about 200 residents.

Images for kids

-

View from the north shoulder of Turtle Mountain. The Frank townsite was where the old road leaves the slide on the left. Frank Lake was created by the slide. Bellevue is at top right. The Interpretive Centre is at left (2013).

See also

In Spanish: Deslizamiento de Frank para niños

In Spanish: Deslizamiento de Frank para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |