Friedrich Kellner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Friedrich Kellner

|

|

|---|---|

Friedrich Kellner in 1934

|

|

| Born | 1 February 1885 Vaihingen an der Enz, German Empire

|

| Died | 4 November 1970 (aged 85) Lich, West Germany

|

| Education | Oberrealschule (High School) |

| Occupation | Justice Inspector |

| Spouse(s) | Pauline Preuss |

| Children | Fred William Kellner |

| Parent(s) | Georg Friedrich Kellner Barbara Wilhelmine née Vaigle |

August Friedrich Kellner (born February 1, 1885 – died November 4, 1970) was a German government worker. He is best known for keeping a secret diary during World War II. In his diary, he wrote down what he saw and heard about the Nazi government.

Kellner was a soldier in World War I. After the war, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany. This was a major political party during Germany's first time as a democracy, called the Weimar Republic. Friedrich and his wife, Pauline, actively spoke out against Adolf Hitler and the Nazis.

During World War II, Kellner worked at a small courthouse. He used his diary to record the crimes of the Nazi regime. He called his diary Mein Widerstand, which means "My Opposition." After the war, Kellner helped remove former Nazis from power. He also helped restart the Social Democratic Party. In 1968, he gave his diary to his American grandson, Robert Scott Kellner. He wanted his grandson to share his story with the world.

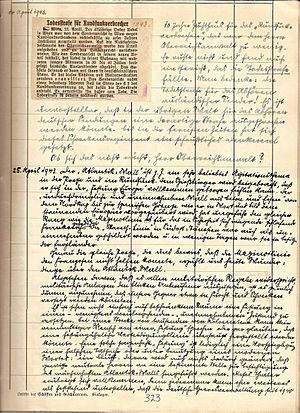

Kellner's diary is very large, with 10 notebooks. Everything was written by hand in an old German style called Sütterlin script. For many years, publishers were not interested in printing it. But in 2005, former US president George H. W. Bush helped show the diary at his George Bush Presidential Library. This made the diary famous. A Canadian film company made a movie about Kellner and his diary in 2007. Robert Scott Kellner translated and edited the diary. It was finally published in German in 2011 and in English in 2018.

Kellner explained why he wrote the diary:

- "I could not fight the Nazis now, because they could silence me. So I decided to fight them in the future. I would give future generations a weapon against such evil. My eyewitness account would record their terrible acts. It would also show how to stop them."

Contents

Friedrich Kellner: A Secret Diary Against the Nazis

Early Life and Family

Friedrich Kellner was born in Vaihingen an der Enz. This town is in southern Germany. At that time, it was part of the German Empire. Friedrich was the only child of Georg Friedrich Kellner, a baker, and Barbara Wilhelmine Vaigle. His family had been Protestant for a long time.

When Friedrich was four, his family moved to Mainz. His father became a master baker there. Friedrich went to school for nine years. In 1902, he finished his exams. This allowed him to train for a job in courthouse administration.

In 1903, he started working as a clerk in the Mainz courthouse. He stayed there until 1933. He moved up in his job. By April 1920, he became a justice inspector.

Fighting in World War I

From 1907 to 1908, Kellner served in the military reserves. He did more training in 1911.

When World War I started in 1914, Kellner was called to active duty. He was a sergeant. In the first month, he fought in eight battles in Belgium and France. His group also fought in the First Battle of the Marne. He was hurt during a long bombing near Reims. He spent the rest of the war working as a quartermaster secretary in Frankfurt am Main.

In 1913, Kellner married Pauline Preuss. Their only child, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm, was born in Mainz in 1916. He was later known as Fred William.

Standing Up to the Nazis

Kellner was happy when Germany became a democracy after the war. In 1919, he became a political organizer for the Social Democratic Party in Mainz. Through the 1920s and 1930s, he spoke out. He warned people about the dangers from extreme groups like the Communist Party and the Nazi Party.

At rallies, Kellner would hold up Adolf Hitler's book, Mein Kampf. He would shout: "Gutenberg, your printing press has been harmed by this evil book." He was often attacked by Nazi thugs, called Storm Troopers.

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler became the leader of Germany. Before Hitler began to arrest his political opponents, Kellner and his family moved. They went to the village of Laubach in Hesse. There, Kellner worked as the chief justice inspector. In 1935, his son moved to the United States. He wanted to avoid serving in Hitler's army, the Wehrmacht.

During the November 1938 attacks on Jewish people and businesses, known as Kristallnacht ("Night of the Broken Glass"), Friedrich and Pauline Kellner tried to stop the violence. Kellner tried to report the riot leaders. But instead, a judge started an investigation into the Kellners' family history. The family's old records proved they were Christians. The case was closed in Kellner's favor. If it had gone the other way, he could have been imprisoned or killed.

Writing a Secret Diary

From reading Mein Kampf, Kellner believed Hitler would start another war. Events soon proved him right. Hitler broke the Treaty of Versailles, rebuilt the German army, and spent a lot on weapons. Other countries were worried but did not stop him. On September 1, 1939, Hitler ordered the German army to invade Poland.

On this day, Friedrich Kellner began his secret diary. He called it Mein Widerstand, "My Opposition". He wanted future generations to know how easily democracies could become dictatorships. He wanted them to see how people believed propaganda instead of fighting against unfair rule.

Kellner did not just write in his diary. He kept speaking his mind. In February 1940, he was warned by a court president to be more careful. A few months later, the mayor and local Nazi leader warned him. They said he and his wife would be sent to a concentration camp if he kept being a "bad influence." Authorities planned to punish Kellner after the war.

For the first two years of the war, Kellner hoped America would help England and France. His diary shows he believed Germany could not win if America joined the fight. When Germany declared war on America in 1941, Kellner became impatient. He wanted the Allies to invade Germany. When the invasion of Normandy happened on June 6, 1944, Kellner wrote in large letters: "Endlich!," meaning "Finally!"

Kellner mostly wrote about Nazi policies, propaganda, and the war. He noted unfairness in the courts. He recorded the cruel actions and plans of the Nazis to kill many people. He believed the German people were partly responsible. They voted Hitler into power, then let him abuse that power.

One important entry was on October 28, 1941. Many Germans later said they knew nothing about the killing of Jewish people. But Kellner's diary shows that news of these terrible acts reached ordinary people early in the war:

- A soldier on vacation here said he saw terrible acts in Poland.

- These cruel acts were so bad that some helpers had nervous breakdowns. All soldiers who knew about these evil Nazi actions thought the German people should be very afraid of what was coming.

- No punishment would be hard enough for these Nazi beasts. Of course, when punishment comes, innocent people will suffer too. But because ninety-nine percent of Germans are guilty, directly or indirectly, for this situation, we can only say that those who travel together will hang together.

After the War: A Legacy of Truth

The war ended for Kellner on March 29, 1945. American soldiers marched into Laubach. Kellner was appointed deputy mayor. He helped with the denazification process. This meant removing former Nazis from power. Kellner also helped restart the Social Democratic Party in Laubach.

Kellner wrote only a few more entries in his diary. On May 8, 1945, the day Germany officially surrendered, he wrote:

- "If, after this collapse, any of Hitler's followers dare to say they were just harmless observers, let them feel the anger of humanity... Anyone who misses the Nazi system or wants to bring it back should be treated as crazy."

Kellner worked as chief justice inspector until 1948. He retired in 1950. For three years, he was a legal advisor. In 1956, he returned to politics. He was Laubach's leading councilor and deputy mayor until he retired in 1960 at age 75.

In 1966, Kellner received money from the Federal Republic of Germany. This was because of the unfair things done to him by the Nazis. The government said Kellner's opposition was known. They had taken steps against him. They noted he was not active enough for the Nazi movement. They also said he caused trouble with the local party. His open opposition stopped him from getting promotions and harmed his career.

Kellner and his wife sent their son, Fred William Kellner, to the United States in 1935. They worried he might have to fight for Hitler. Fred William returned to Germany in 1945 as a US Army soldier. He found it hard to deal with the destruction he saw. He passed away in 1953. He is buried in France.

Fred's son, Robert Scott Kellner, grew up in Connecticut. In 1960, while in the United States Navy, Robert found his grandparents, Friedrich and Pauline Kellner. He learned about the diary. In 1968, Friedrich Kellner gave his diary to his grandson. He wanted it translated and shared. He believed his observations from World War II could help people understand new conflicts.

Friedrich and Pauline Kellner spent their last years in Mainz. Friedrich died on November 4, 1970, in Lich. He was buried next to his wife in Mainz.

Decades later, Robert Scott Kellner used the diary to fight against the return of fascism and anti-Semitism. He also used it to challenge people who denied the Holocaust. He offered a copy of the diary to the former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Ahmadinejad had called the Holocaust "a myth." Robert Scott Kellner said: "We must reject ideas that do not value human life and freedom above all else."

Works

The Diary: My Opposition

My Opposition has 10 volumes. It has 861 pages in total. The pages are accounting paper tied together with string. There are 676 entries, each with a date, from September 1939 to May 1945. More than 500 newspaper clippings are glued onto the pages. The diary is written in Sütterlin script. This was an old German handwriting style. It was banned in 1941.

There are also separate pages from 1938 and 1939. These are like an introduction to the diary. They explain Kellner's goals. He wanted his writings to show what happened during those years. He also wanted to give future generations a way to prevent what happened in Germany. He saw how a new democracy willingly accepted a dictatorship. Kellner knew Germany would lose the war. He warned against any return of totalitarianism. He believed people should always fight against ideas that threaten freedom and human life.

The full diary was published in German in 2011. It has two volumes and about 1,200 pages. It includes over 70 pictures. The title is "Friedrich Kellner, 'Vernebelt, verdunkelt sind alle Hirne,' Tagebücher 1939-1945."

The English translation was published in January 2018 by Cambridge University Press. Robert Scott Kellner translated and edited it. It is one book with 520 pages and 53 pictures. The title is "My Opposition: The Diary of Friedrich Kellner -- A German against the Third Reich."

See also

In Spanish: Friedrich Kellner para niños

In Spanish: Friedrich Kellner para niños