Gershon Agron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gershon Agron

|

|

|---|---|

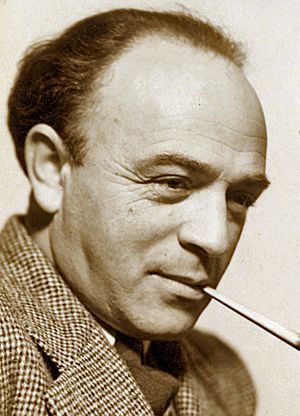

Agron in the 1930s

|

|

| Mayor of Jerusalem | |

| In office 1955–1959 |

|

| Preceded by | Yitzhak Kariv |

| Succeeded by | Mordechai Ish-Shalom |

| Director of the Israeli Government Information Services | |

| In office June 1949 – 1951 |

|

| Director of the Zionist Executive Press Office | |

| In office 1924–1927 |

|

| Director of the Zionist Commission Press Office | |

| In office 1921–1921 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Gershon Harry Agronsky

27 December 1893 Mena, Russian Empire |

| Died | (aged 65) Jerusalem, Israel |

| Nationality | American Israeli |

| Political party | Mapai |

| Spouse |

Ethel Agronsky

(m. 1921–1959) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | See #Family |

| Education | Dropsie College Gratz College Temple University University of Pennsylvania |

| Signature |  |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1918–1920 |

| Unit | Jewish Legion |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | British War Medal Victory Medal |

Gershon Harry Agron (Hebrew: גרשון אגרון, né Agronsky; 27 December 1893 – 1 November 1959) was an important Israeli newspaper editor and politician. He served as the mayor of West Jerusalem from 1955 until he passed away in 1959.

From a young age, Agron was a strong supporter of Zionism, which is the movement to create and support a Jewish homeland in the land of Israel. He joined the Jewish Legion, a group of Jewish soldiers, and fought in the region of Palestine near the end of World War I. He quickly became a spokesperson for Jewish people in America.

Later, he worked as a press officer for Zionist groups and helped grow the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. He moved to Palestine permanently in 1924. He then started his own newspaper, The Palestine Post, which was later renamed The Jerusalem Post after Israel became a country. Around this time, he also changed his last name from Agronsky to Agron.

Agron continued to work in public relations for the new Israeli government. In 1955, he became the mayor of West Jerusalem. He worked hard to develop the city and sadly died while still in office. He is remembered as a very influential supporter of Zionism.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Gershon Harry Agron was born Gershon Harry Agronsky in Mena, a town in what is now Ukraine. His birthday was 27 December 1893. His parents were Yehuda Agronsky and Sheindl Mirenberg. His grandfather was a rabbi, and his parents hoped he would become one too.

He received a traditional Jewish education as a child. In 1906, his family moved to the United States. He grew up in Philadelphia, where he went to school and became friends with Israel Goldstein. When they were 14, Agron and Goldstein started a Zionist club for boys in Philadelphia.

Agron went to several universities in Philadelphia, including Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania. His university studies introduced him to Western culture. He was a strong supporter of Labor Zionism, a type of Zionism focused on workers' rights. By 1917, his views changed, and he became a General Zionist, supporting a broader range of Zionist ideas.

In 1914, Agron wrote to Arthur Ruppin, a leader in the World Zionist Organization. He expressed his wish to move to Palestine and asked for advice on whether farming or engineering would be more helpful for building a Jewish homeland.

In 1915, Agron started working as a journalist for Jewish newspapers in the United States. He wrote obituaries and editorials for The Jewish World. In 1917, he became the editor of Das Jüdische Volk, a newspaper for the World Zionist Organization. He was fluent in English, Yiddish, and Hebrew.

Career Highlights

Serving in the Jewish Legion (1918–1920)

Agron joined the Jewish Legion in April 1918. He became a corporal and then a sergeant during his training in Canada and England. He was part of the 40th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. In Canada, Agron helped recruit others for the Legion, including David Ben-Gurion, who would later become Israel's first Prime Minister.

Agron was chosen early on to be a spokesperson for American Jews. He became a public speaker on Zionism during his visits to London. He was even demoted twice for leaving his post without permission to give these speeches.

Agron fought in Palestine during World War I. He sent reports back to the Zionist Organization of America from the front lines. In 1919, he wrote a pamphlet called "Survey of the Jewish Battalions" for the Zionist Commission. This report highlighted the strong support for the Legion among American Jews.

He was released from military service in 1920. He spent his last months in the military working with Legion records. He "borrowed these papers for safe keeping" because he thought they might be destroyed. In 1922, Agron helped start the American Jewish Legion organization in New York. Its goal was to help Jewish ex-service members settle in Palestine. He was one of the first Americans to live permanently in Palestine.

Working in Press Offices (1921–1932)

After leaving the Jewish Legion, Agron lived in Jerusalem. From 1920 to 1921, he worked for the Press Office of the Zionist Commission. In 1921, he became the head of this office. This role took him to the United States with a delegation that included Albert Einstein. This group helped create Keren Hayesod, a fundraising organization for Israel.

Agron then moved to the United States in 1921 to help set up the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) in New York. He became its news editor. He saw himself as a journalist first and wanted to be separate from the bureaucracy of the Keren Hayesod foundation.

While in the United States, he worked to promote Zionism to politicians and raise money for Palestine. In June 1921, Agron showed the public that US President Warren G. Harding and Vice President Calvin Coolidge supported a Jewish state in Palestine.

He remained the editor of the JTA until he returned to Palestine in 1924. He also worked as a correspondent for international newspapers like The Times and Manchester Guardian. He was eager to move to Palestine but wanted to make important connections in journalism first.

In 1924, he became the Director of the Zionist Executive's Press Office in Jerusalem. This role was also known as Commissioner of Press Relations for the Jewish Agency and head of the Government Press Office (GPO). His main job was to represent the Jewish community in Palestine to the world. He encouraged tourism and immigration by working with global media.

Agron tried to get the Associated Press to publish his pro-Zionism articles, but this often failed. The United States media at that time was focused on its own country and was not keen on publishing news about the Jewish community in Palestine.

Agron was the only established English-language journalist in Palestine. He was in high demand when local events, like the 1927 Jericho earthquake, caught international attention. He wrote for many news services. He also wrote for The Christian Science Monitor.

Leading The Palestine Post (1932–1948)

Gershon Agronsky ... started the paper with the idea that it would present the case of the yishuv, or Jewish establishment in Palestine, to the British in a language and style they could understand.

After a deal with Hearst, Agron started writing the Palestine Bulletin for the JTA. He wanted to start his own newspaper with a clear political purpose, especially after the 1929 Palestine riots. In 1932, he suggested an English-language newspaper for Palestine to Ted Lurie, another young American settler. They raised money in London and published the first copy of The Palestine Post on 1 December 1932.

Initially, the newspaper printed 1,200 copies and was read mainly by British soldiers and German immigrants. Agron made sure the content appealed to these readers, even including cricket results. The Post strongly supported the Israeli Labor Party (then called Mapai). Agron and later editors openly stated that the newspaper was more interested in supporting the creation of Israel than in strict freedom of the press.

Agron admitted that The Post deliberately downplayed Arab opposition to Israel and made Palestinian Arab views seem less important. However, the newspaper was considered very valuable for promoting the Jewish Agency's message. Even though it was independent, it was seen as a semi-official voice.

The staff called Agron "GA." He treated them like family but ran the newspaper like his own kingdom. His nephew, Martin Agronsky, who later became a famous American television journalist, was one of the paper's first reporters.

When the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine began, more British troops arrived, and the newspaper's circulation grew to about 20,000. It became even more successful during World War II. Agron became a war correspondent, covering the North African campaign from 1941 to 1943. He also visited Turkey when the MV Struma, a ship carrying Jewish refugees, sank. He blamed the Allies for this tragedy.

The Post worked to be an anti-Nazi "fighting paper." However, it sometimes disagreed with British policy. For example, an issue was censored in 1936 for reporting on Arab terrorism. Articles criticizing the White Paper of 1939 (which restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine) and deportations left blank spaces in the newspaper. These efforts made The Post a very reliable source of information for the foreign press.

During the 1947–1949 Palestine war, the newspaper published daily editions, which were important for morale. The offices were often attacked by the Arab Legion because of the paper's influence. On 1 February 1948, the office building was bombed. Agron was not in his office at the time. The newspaper was still printed the next day, though it was shorter. Agron refused to leave Jerusalem, and work continued in the damaged offices.

The newspaper was renamed The Jerusalem Post on 13 May 1950, celebrating Israel Independence Day after Israel became a state. Its purpose changed, and it became a key way to defend Israel to foreign diplomats.

Agron also served as an envoy for the World Zionist Organization and attended International Zionist Congresses. He investigated the conditions of Jews in various countries. In 1945, he was part of the Jewish Agency delegation to the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco, where the United Nations was founded.

Information Office and Mayoralty (1949–1959)

After the 1947–1949 Palestine war, the Israeli Information Services were created, led by Agron. He had suggested this in January 1947. When he took the role of Information Chief in June 1949, he changed his name from Agronsky to Agron. He also took a break from being editor of The Post. He had hoped to become Israel's ambassador to Britain but took this role out of duty. He left the Information Chief role in 1951 because it lacked independence and budget.

He returned to The Post full-time in 1951 but traveled to the UK and US for fundraising. He found the travel tiring and stopped.

In September 1955, he was elected mayor of West Jerusalem for a four-year term. He officially resigned as editor of the newspaper. Becoming mayor was "an honor and task that he dreamed of." He took the role during a time when the city government was struggling.

As mayor, he faced many financial challenges from the war. Under Agron, there were fewer arguments in the city council. He could quickly end debates by reminding everyone that time cost money.

During his term, he played a key role in developing the western parts of the city. He brought infrastructure and utilities to neighborhoods. He also improved employment by offering tax breaks to companies that moved to Jerusalem and hired people. He raised money through more efficient tax collection. Despite his modernizations, he worked to preserve the city's unique character. Some people criticized his modernization efforts, especially his decision to open public swimming pools. He remained in office until his death in 1959.

Views on Zionism

Agron was a leading and influential Zionist. He had been both a Labor Zionist and a General Zionist, and he died as a member of the Mapai party. He had his own unique views on Zionism. As a young man, he was greatly influenced by the work of Shmaryahu Levin. He became a pioneer in hasbara (public diplomacy) after becoming unhappy with British control over Palestine.

One thing that made Agron more successful than other young Zionist journalists was his belief that it was important to engage with Jewish communities outside of Palestine (the "diaspora") and with non-Jews. He believed this was the only way to create and protect the Jewish community in Palestine.

On his deathbed in 1959, Agron agreed to an international edition of the Jerusalem Post. The newspaper saw this as a recognition of "the growing importance of the Diaspora." However, on a visit to the United States in 1952, Agron reportedly said, "We [people of Israel] are no longer concerned with the attitude of others… Now, only our actions are significant."

In 1925, Agron wrote that many American Jews were needed to build a successful society in Palestine. However, he warned that potential immigrants needed to understand what moving there would mean.

Agron believed that Israel needed to become a one-party state because he felt there were too many parties to work together effectively. He thought that for Israel to succeed, it needed "Zionism, a strong army, good management and well organized labor."

Family Life

Gershon Agron was married to Ethel (born Lipshutz) until his death. They married in April 1921 in the United States. Agron only told his wife after they married that he expected her to move to Palestine with him, which she did, though she was hesitant at first.

When they moved to Jerusalem, they lived in a spacious villa in Rehavia. They had three children: a son named Dani Agron (1922–1992), and two daughters, Varda Tamir (1926–2008) and Judith Mendelsohn (1924–2006).

When Agron's children were young, they attended Debora Kallen's Parents Educational Association School in Jerusalem. This was an advanced but strict school. When World War II started, Agron and other important figures worried about the Nazis invading Palestine. He sent his children to kibbutzim (communal settlements), where they lived during the war for safety.

Varda, his daughter, later said that this attempt at protection was naive. She noted that she struggled to understand Holocaust survivors who arrived after the war. She felt this was due to an "unjustified arrogance" from Zionist education, which sometimes made non-Palestinian Jews seem different.

His children attended Beit Hakerem High School. Varda was the only one of the siblings to graduate high school. Dani was often expelled for bad behavior and went to a vocational school in Haifa. Judith was more focused on being a housewife.

Ethel Agron was born Ethel Lipschutz. She attended William Penn High School and Goucher College. In Palestine, she was active in public life. She worked with the Hadassah Women's Zionist Organization of America and was on the Hadassah Council in Palestine and Israel. She was head of the Hadassah Youth Services Committee and, in 1948, head of the Hadassah Council in Palestine. She took her role seriously, campaigning for children and writing for Hadassah Magazine. She was also on the Israeli government's Social Service Advisory Committee. During the Israel-Palestine war, Ethel helped run emergency Hadassah medical centers, often in secret locations without water or power.

Daniel "Dani" Agron was born in New York but grew up in Palestine. He was part of the Jewish Brigade and Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organization. He smuggled weapons for the Israel Defense Forces during the Israel-Palestine war. He also helped start Israel Aerospace Industries with Shimon Peres. As a leader in the Haganah, Dani Agron managed a secret flying school and its pilots. He sent them around Europe to learn to fly planes that the group could get, even former German World War II planes.

Dani loved planes but could never pilot one himself due to poor eyesight. In 1956, he drove over a landmine from the Suez Crisis and lost a leg. In the 1960s, he started a cropdusting company called Merom Aviation Services. In the 1970s, Dani Agron worked as the business manager of The Jerusalem Post. He was also a skilled woodcarver. Later in life, he faced challenges with mental illness.

The Agron family was one of the wealthiest in Jerusalem. However, Gershon Agron tried to appear as if he lived simply to fit in with Zionist ideals. He was also very anxious about his success and tried to hide it. He often took in immigrants to Israel before they settled and gave jobs to aspiring journalists at The Post.

Even though the family was sometimes seen as outsiders because they were American, they were popular in Jerusalem's social life. They were friends with many important figures. "Foreign and Israeli journalists, Arabs, Englishmen and Jews all met at the Agrons to talk politics and drink tea." They were at the center of social life from the moment they arrived.

Death and Legacy

Agron was admitted to the Hadassah Medical Center in September 1959 for liver surgery to treat cancer. After the surgery, he got pneumonia and passed away from this infection on 1 November 1959, at age 65. A year before his death, he had approved the opening of a public swimming pool where men and women could swim together. Some very religious rabbis were unhappy with this decision.

At the time of his death, Agron was running for re-election as mayor of Jerusalem. The vote was set for 3 November 1959.

He received a state funeral, attended by over 40,000 people. Moshe Sharett, a former Prime Minister of Israel, gave a eulogy, calling him "one of the greatest personalities of the Zionist movement." He was buried at Har HaMenuchot, a cemetery in Jerusalem.

Agron Street in downtown Jerusalem and Agron House, the former headquarters of the Israeli Press Association, are named after him. The cornerstone of Agron House was laid on 10 October 1961. At the ceremony, Israel Goldstein praised Agron as an excellent journalist and an ambassador for Israel and Zionism. He said Agron "radiated" the light of Zion to both Jews and non-Jews.

In 1950, he was called "one of the most influential and courageous spokesmen" for the Jewish community in Palestine. In 2012, Ulf Hannerz described Agron as "a culture hero of Israeli journalism."

Gershon Agron's personal papers are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem. His diaries were published after his death in 1964.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |