Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marquis de Lafayette

ORMSL

|

|

|---|---|

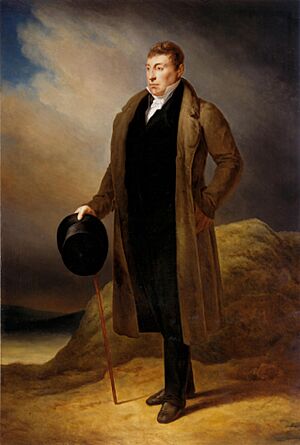

Lafayette as a lieutenant general in 1791, by Joseph-Désiré Court (1834)

|

|

| Birth name | Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette |

| Nickname(s) | The Hero of the Two Worlds (Le Héros des Deux Mondes) |

| Born | 6 September 1757 Château de Chavaniac, Auvergne Province, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 20 May 1834 (aged 76) Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of France (1771–1777, 1781–1792, 1814/15–1830) United States (1777–1781) French First Republic (1792) |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1771–1792 1830 |

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Order of Saint Louis |

| Spouse(s) |

Adrienne de Noailles

(m. 1774; died 1807) |

| Children | 4, including Georges Washington |

| Signature |  |

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (September 6, 1757 – May 20, 1834), known simply as Lafayette, was a French nobleman and military officer. He became a hero in the American Revolutionary War when he volunteered to join the Continental Army under General George Washington.

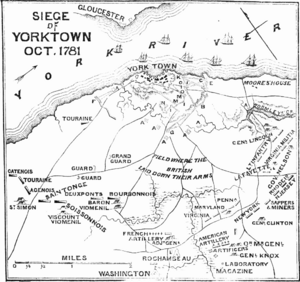

Lafayette was a key leader in both the American and French Revolutions. He commanded American soldiers in the final major battle of the war, the siege of Yorktown, which helped secure America's independence. Because of his actions in both countries, he is often called "The Hero of the Two Worlds."

Contents

A Noble Beginning

Lafayette was born in Chavaniac, France, to a rich and powerful family with a long history of military service. His father was a colonel who was killed in battle when Lafayette was only two years old. This left Lafayette with the title of "marquis" and a large fortune.

He grew up hearing stories of his family's bravery. Following tradition, he became a military officer at just 13 years old. When he was 14, he arranged to marry Adrienne de Noailles, a 12-year-old girl from another powerful family. They fell in love and were married in 1774.

The Fight for American Freedom

A Cause to Believe In

In 1775, as a young officer, Lafayette heard about the American Revolution. The American colonists were fighting for freedom from British rule. Lafayette believed their cause was noble and just. He felt a strong desire to help them fight for liberty.

He met with American agents in Paris, including Silas Deane, and offered to serve. On December 7, 1776, Deane signed him up as a major general in the Continental Army. Lafayette was only 19 years old.

The French king, Louis XVI, did not want his officers fighting in America and forbade Lafayette from going. But Lafayette was determined. He secretly bought his own ship, which he named Victoire (Victory), to sail to America. He landed near Georgetown, South Carolina, on June 13, 1777.

Joining the Continental Army

When Lafayette arrived in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress was unsure what to do with him. But after he offered to serve for free, they made him a major general.

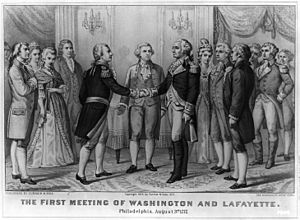

Soon after, he met General George Washington. The two men quickly became close friends. Washington was like a father to the young Frenchman, and Lafayette looked up to the American general. He became a member of Washington's staff.

Bravery in Battle

Lafayette first saw action at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. He was shot in the leg but continued to rally the retreating American soldiers, helping them escape in an orderly way. His bravery impressed Washington, who recommended him for command of his own division.

That winter, Lafayette stayed with Washington and the army at Valley Forge. He shared the terrible hardships of the soldiers, living through the cold and hunger. His loyalty earned him the respect of the American troops.

In 1778, France officially joined the war as an ally of the United States. Lafayette fought in several more battles, including the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey and the Battle of Rhode Island.

Return to France and Second Voyage

In 1779, Lafayette returned to France to ask for more soldiers and supplies for the American cause. He was welcomed as a hero. He successfully convinced the French king to send a large force of 6,000 soldiers to help the Americans.

He returned to America in 1780 aboard the ship Hermione. Washington put him in command of troops in Virginia. His job was to trap the British army led by General Cornwallis.

Victory at Yorktown

In 1781, Lafayette's troops cornered Cornwallis's army at Yorktown, Virginia. Lafayette cleverly used his smaller force to keep the British trapped until General Washington and French forces could arrive.

The combined American and French armies, with help from the French navy, laid siege to Yorktown. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered. The Siege of Yorktown was the last major battle of the Revolutionary War and secured America's independence.

The French Revolution

After the American Revolution, Lafayette returned to France as a celebrated hero. He worked closely with Thomas Jefferson to strengthen the friendship between France and the United States. He also became a strong voice against slavery.

A Call for Change

In the late 1780s, France was facing serious money problems and public anger. In 1789, Lafayette was elected to the Estates General, a meeting of representatives from all parts of French society.

Inspired by the American Declaration of Independence, Lafayette, with help from Jefferson, wrote a draft of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This famous document declared that all people have natural rights to liberty, property, and security.

Commander of the National Guard

After the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, Lafayette was made commander of the new National Guard of Paris. His job was to keep order in the city. He created the famous blue, white, and red French tricolor symbol for the Guard.

Lafayette tried to find a middle path during the revolution. He wanted a constitutional monarchy, where the king would share power with an elected assembly. However, the revolution became more and more extreme. Radical groups wanted to get rid of the king completely.

His popularity suffered after the royal family tried to flee France in 1791. As head of the Guard, Lafayette was blamed for their escape. Later that year, at a protest at the Champ de Mars, his soldiers fired on a crowd, and many people were killed. This event, known as the Champ de Mars massacre, destroyed his reputation with the public.

Exile and Prison

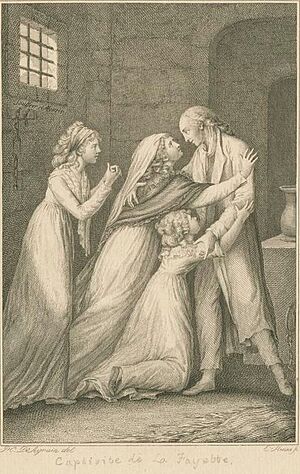

In 1792, radical factions took control of the government and ordered Lafayette's arrest. He was forced to flee France. As he tried to travel to the United States, he was captured by Austrian soldiers and declared a prisoner of state.

Lafayette spent more than five years in dark, unhealthy prisons. His wife, Adrienne, and their daughters were eventually allowed to join him. They lived together in confinement for two years.

In 1797, a young and successful French general named Napoleon Bonaparte negotiated his release.

Later Life

Lafayette returned to France but refused to support Napoleon's government, which he saw as a dictatorship. He retired from public life and lived quietly at his home, the Château de la Grange-Bléneau.

After Napoleon was defeated, the French monarchy was restored. Lafayette was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, where he continued to fight for liberty and representative government.

Grand Tour of the United States

In 1824, President James Monroe invited Lafayette to visit the United States for the nation's 50th anniversary. His return was a massive event. For over a year, he toured all 24 states and was greeted by huge, cheering crowds everywhere he went.

Cities held grand parades and dinners in his honor. He was celebrated as the last living hero of the Revolution. He visited his old friends, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. Congress thanked him for his service by giving him $200,000 and a large piece of land in Florida.

The July Revolution of 1830

Back in France, Lafayette took part in one last revolution. In July 1830, King Charles X tried to take away the rights of the people. Parisians rose up in protest, and Lafayette was once again asked to lead the National Guard.

He helped place a new king, Louis-Philippe, on the throne, hoping he would support a more democratic government. However, Lafayette soon became disappointed when the new king also became too powerful.

Final Years and Legacy

Lafayette died on May 20, 1834, at the age of 76. He was buried in Picpus Cemetery in Paris, next to his wife. As he had requested, his son sprinkled soil from America's Battle of Bunker Hill over his grave.

Lafayette is remembered as a true champion of liberty. He fought for the rights of people in both America and France. Many cities, towns, and parks across the United States are named in his honor, a lasting tribute to the "Hero of the Two Worlds." In 2002, he was granted honorary United States citizenship.

Interesting Facts About Lafayette

- His full name was Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette! That's quite a mouthful, so it's easy to see why he's usually just called Lafayette.

- He was commissioned as a major general in the Continental Army at just 19 years old, making him one of the youngest generals in American history!

- When the American Congress couldn't afford his passage, he bought his own ship, the Victoire, to sail to America and join the fight for liberty.

- He and George Washington formed a deep, father-son-like bond. Washington even named his own son George Washington Parke Custis, and Lafayette named his son Georges Washington Lafayette!

- The Oneida Native American tribe, whom he recruited to the American side, gave him the honorary name "Kayewla," which means "fearsome horseman."

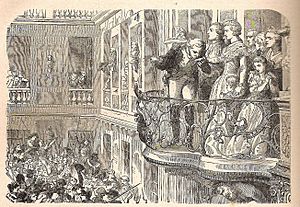

- During the French Revolution, when a mob stormed the Palace of Versailles, Lafayette famously kissed Queen Marie Antoinette's hand on the balcony to calm the angry crowd, earning cheers.

- He was buried in Paris under soil brought from Bunker Hill, Massachusetts, a symbolic gesture connecting him forever to the American Revolution.

- In 2002, the U.S. Congress officially granted him honorary American citizenship, making him only the sixth person in history to receive this special honor.

- During his "Grand Tour" of the United States in 1824-1825, he managed to visit every single one of the 24 states that existed at the time!

- Despite being offered the chance to become a dictator during the July Revolution of 1830, he refused, staying true to his belief in constitutional government and democracy.

- His home in Paris, the Hôtel de La Fayette, became a popular meeting place for American envoys and liberal thinkers, including Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

- He was a lifelong opponent of slavery and even experimented with a plantation in Cayenne where he tried to show that enslaved people could be educated and paid for their labor, hoping to inspire widespread emancipation.

See also

In Spanish: Marqués de La Fayette para niños

In Spanish: Marqués de La Fayette para niños

- List of places named for the Marquis de Lafayette

- LaFayette Motors

- Hermione (2014), a replica of the Hermione of 1779, currently in service

- Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution, a 2021 biography