Henry Morgan's Panama expedition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Henry Morgan's Panama expedition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War (1654–1671) | |||||||

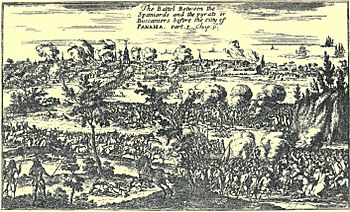

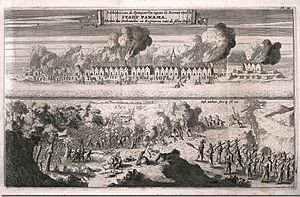

Morgan at Panama 1671 - the top engraving shows the burning and sacking of Panama, the below shows the Battle of Mata Asnillos |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total

Santa Catalina

Fort San Lorenzo

Panama

|

Total

Santa Catalina

Fort San Lorenzo

Panama

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Santa Catalina

Fort San Lorenzo

Panama

|

Santa Catalina

Fort San Lorenzo

Panama

|

||||||

The Henry Morgan Panama Expedition, also known as the Sack of Panama, was a major military journey. It happened between December 16, 1670, and March 5, 1671. This event was part of the later stages of the Anglo-Spanish War.

During this time, English privateers and French pirates joined forces. They were led by the famous Buccaneer Henry Morgan. Their goal was to capture the wealthy Spanish city of Panama. This city was located on the Pacific coast.

Morgan gathered an army of 1,400 men. The expedition began in April 1670. Nine months later, they set sail from Tortuga island, near Hispaniola.

Their first stop was Old Providence Island. They captured it from the Spanish using a clever trick. After leaving a small group of soldiers, part of Morgan's force sailed to the Panama Isthmus. There, they attacked Fort San Lorenzo. This fort was at the mouth of the Río Chagres.

The fort was taken after a tough fight. Morgan and the rest of his force arrived a week later. They used the fort as a base. From there, the privateers marched across the Isthmus. After almost a week of marching through the jungle, many were very hungry. They fought off several Spanish ambushes. Finally, they reached the edge of Panama City.

Outside the city, Morgan's army defeated Spanish soldiers. This battle was called the Battle of Mata Asnillos. After their victory, they quickly took over the city. Panama was then looted and burned. Morgan's army also raided nearby areas and islands in the Gulf of Panama.

Even though they found a lot of treasure, each privateer didn't get as much as they hoped. This was because the army was so large. The privateers then began their journey back across the isthmus. They destroyed Fort San Lorenzo before leaving.

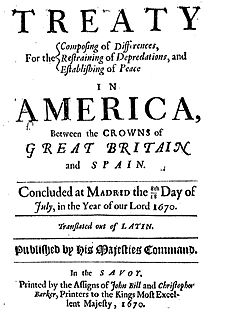

When Morgan returned to Jamaica, he learned about a peace treaty. England and Spain had signed it in March 1670, ending the war. Morgan said he didn't know about the treaty. He was arrested and sent back to England. However, he was seen as a hero and set free. King Charles II even made him a knight. Later, he became the Governor of Jamaica.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

In 1654, Oliver Cromwell started a war with Spain. He planned a big attack on Spain's colonies in the Caribbean. This plan was called the Western Design. The main target was Santo Domingo on Hispaniola. But this attack failed. The expedition then went to Spanish Jamaica and successfully took the island.

After England settled in Jamaica, Spain tried many times to get the island back. Two big attempts were made. But the Spanish were defeated in 1657 and 1658.

In 1660, King Charles II returned to power in England. This ended England's war with Spain. But no peace treaty was signed between the two countries. So, the Caribbean remained in a state of war. The Governor of Jamaica, Thomas Modyford, wanted Spain to officially recognize England's control of Jamaica.

Governors like Modyford invited Buccaneers to base themselves at Port Royal. These included Christopher Myngs and later Edward Mansvelt. They helped defend Jamaica from Spanish attacks. These buccaneers were mostly English, French, and Dutch. They were also known as the Brethren of the Coast. They were given special permission, called Letters of Marque, to raid Spanish ships and towns. This was meant to prevent Spanish invasions.

Over the next few years, they raided Spanish territories. This included the Sack of Campeche in 1663. They also captured Santa Catalina island in 1666. In 1667, England and Spain signed a peace treaty. But it didn't mention the Caribbean. England didn't try to enforce the treaty outside of Europe.

Mansvelt died in 1666. Henry Morgan then took over as the leader of the buccaneers. Morgan was already in charge of Jamaica's defense. Modyford gave Morgan a letter of marque in 1667. King Charles II also gave him a ship, HMS Oxford. Morgan then led successful raids. He attacked Puerto Principe in Cuba, getting a good profit. He also raided Porto Bello in Panama, earning even more. In 1668, Morgan sailed to Maracaibo and Gibraltar in Venezuela. He raided both cities and took their wealth. He also destroyed a large Spanish naval fleet before escaping.

Mariana, the Queen Regent of Spain, was very angry about these attacks. She ordered all English ships in the Caribbean to be seized or sunk. In March 1670, Spanish privateers attacked English trade ships. One of these privateers was Manuel Ribeiro Pardal. In response, Modyford told Morgan to "perform all manner of exploits" to protect Jamaica.

While anchored near Île à Vache, a party was held on the Oxford. During the celebration, the ship's gunpowder storage exploded. More than 200 people died. Morgan was lucky; he and six other captains survived.

Planning the Attack

Despite the accident, Morgan started planning his next attack in April 1670. This time, he wanted to achieve something bigger. He aimed to capture an important Spanish port. Morgan knew he needed a large army for this. He started a huge recruitment effort. He recruited English fighters from Jamaica and French fighters from Tortuga and Hispaniola. Morgan believed this would be his last major voyage. He knew peace with Spain in the Americas was coming soon.

As the expedition prepared, more privateers arrived. Captain Collier was sent with six ships to Rio de la Hacha. His mission was to get supplies and information from locals. He captured the Spanish stronghold there. He also got provisions and weapons from the local people.

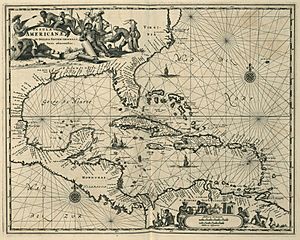

On October 24, Morgan held a meeting with all his captains. They decided where to attack. Morgan suggested three places: Panama, Cartagena de Indias, and Veracruz. Everyone agreed that Panama was the best choice. It was considered the richest city. Panama was the second-largest city in the Western Hemisphere. It had over 7,000 households and was a busy trading center.

Every year, the King of Spain's ships carried silver from Peru's mines to Panama. From Panama, the silver was taken by mules to Portobello. There, it was loaded onto ships for Spain. To succeed, Morgan needed a way to get supplies and communicate. He planned to take Providence Island and Fort San Lorenzo. Guides would then lead his army from there to Panama.

Providence Island had been an English colony before. Morgan had captured it once already. He knew it had Spanish bandits and criminals who would help for money. Morgan planned to lead over 1,000 men along the Chagres River. They would follow part of the old 'Camino de Cruces' (Way of the Crosses). This was a Spanish route used to transport goods across the Isthmus of Panama. Morgan wanted to follow in the footsteps of Francis Drake. Drake had succeeded along this route almost a century earlier.

Morgan read out the rules for the expedition. They were very generous. Captains would get eight shares of the treasure. There was also compensation for injuries. Brave actions would earn a bonus of fifty pieces of eight.

Ships from as far as New England joined. By the end of October, Morgan had 30 to 36 English and French ships. They were ready to carry a large number of privateers. Morgan was given the captured French ship Satisfaction. It was the largest ship and could hold eight boats. There were twelve other ships with ten or more guns. Each carried about seventy-five men. The other 25 ships were smaller, some without any guns.

The exact size of Morgan's force varies in different reports. But there were at least 36 ships. They carried as many as "2,000 fighting men, besides sailors and boys." Most of the force came from the British Isles and its colonies. However, there were also about 520 French fighters. There were also Dutch, free black people, Native Americans, Portuguese, and even a few Spanish who had turned against Spain.

At that time, this privateer army was the largest ever gathered in the Caribbean. They were well-armed and ready to fight for the rich treasure. This showed how famous Morgan was.

Many well-known fighters of the time were part of the privateers:

- Edward Collier was made Vice Admiral.

- Joseph Bradley was an experienced buccaneer and captain.

- Robert Searle had just been released from prison. He had sacked St. Augustine in Florida in 1668.

- Lawrence Prince was a Dutchman. He had just returned from a successful raid up the San Juan river. He had sacked Granada in 1669. He was appointed third in command.

- John Morris was a hero. He had a famous fight with Manuel Ribeiro Pardal. Morris killed Pardal and took his ship.

- Alexandre Exquemelin was a French/Flemish writer.

Other members included Francis Witherborn and Dutchmen Jan Erasmus Reyning and Jelles de Lecat.

Collier rejoined Morgan's fleet in early December. He brought back several prisoners. These prisoners said that Spain was preparing to invade Jamaica. This gave Morgan more reason to launch his attack.

Around this time, Morgan received a letter from Modyford. It said that peace had been signed between England and Spain in July. But it was still waiting to be officially approved. Meanwhile, the Spanish also heard this news. They received reports of the privateers gathering at Île-à-Vache. The Spanish were alarmed about an attack on their territories. Most thought Cartagena de Indias was the target. So, Governor Don Pedro de Ulloa prepared the city's defenses.

Other parts of the Spanish Main were also on alert. This included the Chagres River defenses. These were organized by Governor Don Juan Pérez de Guzmán y Gonzaga. He had about 400 men. They prepared four strong points with tall fences upriver. They also set up lookouts and canoe patrols.

The Expedition Begins

Morgan organized his fleet and left Hispaniola on December 16. He divided his fleet into two groups. They now sailed under official orders, as part of Great Britain's naval power. Morgan's main group sailed under the English Red Ensign. The other group was led by Joseph Bradley. It sailed under a White Flag with three small red squares. Each ship also carried the Royal standard at its front.

Capturing Old Providence and Santa Catalina

Morgan sailed to capture Old Providence Island and the smaller, connected Santa Catalina. He arrived at Providence on December 20. He landed a thousand men and marched through the woods. There was little resistance, and the island seemed empty.

Santa Catalina, however, had strong defenses. It had eight forts. The largest was Fort San Jerome. Rain poured down as Morgan's men advanced to the drawbridge connecting to Santa Catalina. Morgan wanted to take the island quickly to avoid delays. He tricked the Governor into surrendering. He threatened to show no mercy if the Governor refused. To Morgan's surprise, the Governor surrendered easily. But he asked for a fake attack so he could surrender with "some honor." Morgan agreed. He made sure to protect his men and the 450 residents, including 190 soldiers.

The privateers gained 48 cannons, 170 muskets, and over 30,000 pounds of gunpowder. Morgan released the Spanish criminals. Three of them even agreed to guide him across the Panama Isthmus.

More privateers joined Morgan at the island. This included Colonel Bledry Morgan (no relation). He gave Henry a letter from Modyford approving the expedition. After taking the island, Morgan left 130 men to guard it. They destroyed all the forts except San Jerome. He then ordered four ships and a boat, with 400 men, to go and take Fort San Lorenzo. This force was led by Captain Joseph Bradley. Morgan sent them ahead so the Spanish wouldn't guess his real target.

Attacking Fort San Lorenzo

Four days after leaving Santa Catalina, Bradley and his four ships arrived near Fort San Lorenzo. This fort was at the mouth of the Río Chagres. It was built on a tall mountain with steep rocks all around. It could only be reached from the land side. A drawbridge provided access. There were also casemates (fortified gun positions) and palisades (strong fences).

The Spanish, led by Don Pedro de Lisardo, saw the ships. They raised their flag and prepared their cannons. They had increased their soldiers to 314 men. They also improved their defenses and added more cannons, totaling twenty.

The privateers anchored a short distance from the fort. The next morning, they launched a direct attack. But it was pushed back with heavy losses. They couldn't get past the fort's ravine. Bradley didn't give up. He ordered another attack at dusk. As darkness fell, the privateers moved forward again. They faced heavy fire and couldn't advance further. However, they managed to throw grenades, setting several houses on fire. One lucky shot hit the fort's gunpowder storage. The explosion caused confusion among the defenders. This allowed the English to break into the fort.

Brutal hand-to-hand combat followed. No mercy was given. The English took the fort's guns and turned them on the defenders. Lisardo refused to surrender and was killed. The few remaining Spanish soldiers surrendered. The English took control and put out the fires.

Out of 314 defenders, only fourteen were taken prisoner. The privateers had 30 killed and 160 wounded. Bradley, who was injured during the attack, died from his wounds. Fifty of the wounded also died. Captain Richard Norman took command of the fort and waited for Morgan's fleet.

Four days later, Morgan arrived at the fort and saw the English flag flying. As they approached, four of his ships ran aground on hidden reefs. Three of them, including the Satisfaction, sank. Ten men were lost. Morgan managed to transfer what was left to the other ships. He stayed at the fort for a week. He repaired it using prisoners from Santa Catalina. Morgan needed to make sure the fort was strong enough against a Spanish counterattack. He left 150 men to guard the fort and 150 men on the ships. This protected his escape route. During this time, an English scouting group captured several small Spanish boats. Each had two guns. They had been used to carry cargo down the river. Morgan used them to carry many of his men on the journey.

-

.

A map of Fort San Lorenzo and the mouth of the Chagres River.

Marching Across the Isthmus

- January 19

Early in the morning, Morgan and about 1,400 men began their journey. They used seven small sailing vessels and thirty-six canoes. They went up the Rio Chagres. The trip to Panama was about fifty miles. Much of it would be on foot, through thick rainforests and swamps.

About half the troops walked along the river. The other half traveled by canoe and boat, each with a guide. On the first day, they made good progress. The privateers traveled about eighteen miles. They reached their first stop, Dos Brazos. Gonzalez Solado, the captain of the river, was waiting for them there. He had planned an ambush. But he soon realized how many enemies they faced. Solado saw they were greatly outnumbered. He ordered a retreat and fled. The Spanish destroyed everything. So, the privateers found nothing of value or food when they arrived.

- January 20

After staying the night at Dos Brazos, they set out early. They soon noticed the river became harder to navigate. It was the dry season, which made things difficult for Morgan and his men. They reached a place called Cruz du Juan Gallego. They had to leave their boats because the Chagres River was low. It was hard to move through areas with mangrove roots and rotting trees. As the jungle thinned, Morgan landed his men. They traveled overland, dragging the canoes. Morgan left 160 men to guard the boats.

- January 21

Governor Guzman was kept informed of Morgan's advance. He hoped that Spanish troops, hunger, and disease would defeat the privateers. Guzman used a "scorched earth" tactic. This meant destroying everything useful. He was sure the English wouldn't get through. However, Morgan's guides were very helpful. They walked ahead with twenty to thirty men to prevent ambushes. Around noon, they found a swamp. They couldn't find a road or a way forward. But they managed to create a path to a place called Cedro Bueno. Progress was slow. It had been three or four days since most had eaten. Many became weak. Some ate leaves and other plants, with mixed results.

- January 22

By morning, they reached Barro Colorado. Two canoes that rowed ahead returned. They reported finding an ambush. The privateers prepared and started making war cries. This tactic worked. They soon found the ambush site empty. It had a strong, crescent-shaped fence made of trees. When they left, they took provisions and burned what they couldn't carry. Morgan saw he couldn't find food. He pushed his men to advance as long as possible. They walked the rest of the day, cutting through the jungle. In the evening, they arrived at Torna Munni. They found another abandoned ambush site. By nightfall, they slept on the riverbanks. The nights were cold at this time of year.

- January 23

The next day, the expedition reached Barbacoa. This was the first Spanish village they found. It was also the first defensive outpost. They found it burned and empty. Captain Castillo and his 216 men had left, fearing they would be cut off. There were several houses. The English searched everywhere. They found two sacks of flour buried in the ground and some plantanos (plantains). That was all. Some men were so hungry they ate leather bags left by the Spanish. By the end of day five, they moved to another outpost called Torno Marcos. Again, Morgan's men expected an ambush but found nothing. They rested there for the night.

- January 24

They continued their journey, but many were too weak to go on. Around noon, the privateers reached the village of Venta de Cruces. They found an outlying house full of corn and a leather bag of bread. Soon after, they saw some Native Americans walking ahead. They chased them, thinking they would find a Spanish ambush. The Native Americans crossed the river and escaped. The men settled in Venta de Cruces for the day.

- January 25

The Chagres River turned northeast at the village. So, the privateers crossed the river and continued on land. They left their boats and canoes at Venta de Cruces to be sent back downriver. One boat was left in the village with a small group of men to protect Morgan's communication line. Panama was now only 25 miles away. As they passed Gamboa, the terrain became harder. Mountains began to rise on each side. By noon, they reached the village of Cruz. The residents had left after setting fire to the houses. Only the king's shops and stables remained. Starving, the privateers killed and ate all the dogs in the stables. They rested before setting off the next morning. Morgan wondered if he could continue to Panama, with many still starving and getting sick.

- January 26

In the morning, they set off. The road became narrower and steeper. Morgan chose 200 men to go ahead of the main group. They found several narrow passages where only two men could walk side by side.

At noon, they arrived at Quebrada Obscural. Here, Salado had set up his last ambush point. He sent about 300 Native American archers and 100 Spanish musketeers. They were led by a Black captain, Joseph de Prado, one of the few survivors from San Lorenzo fort. The privateers were surprised by a rain of arrows. Eight to ten men were killed, and many were wounded. However, the privateers' tactics worked. The ambushers were driven off with some losses. One group of Native Americans fought until their chief was badly wounded, forcing them to retreat. Despite this attack, the privateers continued their advance. By late evening, the jungle and mountains began to thin out. They soon reached open grassland, called savannah, where there was less danger of ambushes. In the evening, they stopped at a group of houses to rest and sleep.

- January 27

In the morning, a scouting party climbed Ancon Hill. From the top, they could see the Pacific Ocean. They also saw a ship with five boats leaving Panama. Their destination was a group of islands (likely Taboga and Taboguilla). The scouting party went down into a valley. There was a meadow full of cattle. Many Spanish horsemen were herding them. When the privateers arrived, the Spanish horsemen left the animals to save themselves. The cattle and horses were all killed. The hungry privateers had a big Barbecue feast. They rested for most of the afternoon before setting off again. Soon, they began to see the roofs and spires of Panama.

Morgan then set up camp for his 1,200 men for the night. The Spanish governor, Don Guzmán, was alerted to the privateers' arrival. He quickly prepared Panama's defenses. Two groups of cavalry and four groups of foot soldiers were brought up. They were stationed on the savannah. The Spanish outnumbered Morgan's men by almost two to one. To discourage an attack, Morgan had drums beating, trumpets blowing, and flags displayed. The Spanish also did the same. Their morale was high. One soldier reportedly said, "we have nothing to fear. There are no more than 600 drunkards."

The Battle of Mata Asnillos

On January 28, Morgan's force prepared for battle. They faced about 1,200 Spanish foot soldiers and 400 cavalry. Although the Spanish outnumbered Morgan's force, most were not experienced. Only 600 had firearms. The rest mainly had sharp weapons like machetes, pikes, and spears. Guzman arranged his foot soldiers in a line, six men deep. Two groups of cavalry were on each side. Behind them were two herds of oxen and other livestock. These were ready to be released by herders. Guzman hoped to let the buccaneers pass through his lines. Then, he would release the herds to disrupt them just before the Spanish soldiers attacked.

Morgan arranged his army for battle. They were just outside cannon range, on a plain behind the Matasnillo River. The Spanish were on the other side. Laurence Prince and John Morris led the main force of about 600 men. Morgan and Collier led the right and left sides. Colonel Bledry Morgan commanded the rearguard.

At 7 PM, the two sides advanced toward each other. The privateers moved forward in four groups across the plain. Morgan sent one group of 300 men, led by Major John Morris, down a ravine. This ravine led to a small hill on the Spanish right side. As they disappeared, the Spanish thought the privateers were retreating. This made the Spanish defenders attack. Their left side broke formation and chased. Guzman then ordered the rest of his foot soldiers forward.

However, Morgan's main force met them with well-organized gunfire. Nearly 100 men were killed in the first volley. When the privateers' left side, led by Laurence Prince, appeared from the ravine, the Spanish cavalry charged. This charge was led by Francisco Haro. But the ground was muddy, and the cavalry couldn't move well. The privateers fired their muskets accurately from thirty yards away. Many cavalrymen, including Haro, were knocked off their horses. The Spanish cavalry had to retreat.

Meanwhile, the Spanish foot soldier attack weakened, and many began to run away. This caused the Spanish herders to panic. The cattle then wandered among the Spanish lines. Guzman ordered them released, not realizing many already had. Scared by the gunfire, the cattle turned and stampeded over their own herders and then the Spanish troops. The few cattle that reached the privateer lines were shot by the still-hungry privateers. The Spanish line completely broke. Don Juan tried to stop the retreat, but it was useless. The English took control of the battlefield.

The battle was a complete defeat for the Spanish and lasted two hours. Spanish losses were heavy, with between 400 and 600 killed or wounded.

Sacking Panama City

Morgan's men chased the retreating Spanish into the city. They rushed over the bridge at the west end. There was some resistance in the three main streets. Barricades had been set up, but these were quickly overcome. The looting began right away.

Meanwhile, fires started in several parts of the city. The wind helped spread the flames. Don Juan had ordered buildings to be set on fire if the privateers won. The armory also exploded with the remaining gunpowder. The privateers tried to put out the fires, with mixed success. In the confusion, a warehouse of Peruvian wine was found. But Morgan ordered his men not to drink any wine. He claimed the residents had poisoned it. It's more likely he worried that the Spanish, who still greatly outnumbered his force, might counterattack if the privateers became disorganized. Guzman tried to rally some men, but it was no use. Many fled to the islands or hills to escape.

The next day, Morgan sent 180 men to announce the victory at Fort San Lorenzo. He also had trenches built, mainly around the Church of the Trinity Fathers. This was in case of a Spanish counterattack. The men then secured the surrounding area. They couldn't stop some boats from leaving the nearby beach. But the privateers saw they were heading for nearby islands. As they went further down the coast, they captured a barque (a type of sailing ship) at La Tasca. It had just come from Paita and had run aground the day before the battle. Its crew had tried to burn it, but the English quickly captured it intact. It was mostly loaded with corn, but also had biscuits, sugar, soap, and linen. It also had twenty thousand dollars in silver in its cargo hold.

In the city, despite the fires, the privateers found hidden riches. Edward Collier oversaw the questioning of some residents. Morgan's ship doctor, Richard Browne, later wrote that Morgan "was noble enough to the vanquished enemy." Over time, the privateers searched wells and rainwater tanks. They found gold and silver objects thrown in for safety. They dug up hastily buried items in holes, opened floorboards, and looked behind ceilings. They also found many shops full of goods that the Spanish had left behind. Some shops were full of flour, iron tools for Peru, like hoes, axes, anvils, and plows. There was also plenty of wine, olive oil, and spices. Morgan also formed special groups just for looting the city and its surroundings. These search parties went as far as twenty miles into the mountains north and northeast of the city. There was no resistance. Most returned two days later with over one hundred mules loaded with loot and money. They also brought more than two hundred prisoners.

Searching the Gulf of Panama

Morgan learned that the Spanish had sent most of their treasure on ships. These included the Santisima Trinidad and the San Felipe Neri. But these ships had already sailed two days before. Morgan then ordered a search of nearby islands in Panama Bay. He knew many Spanish citizens and soldiers had fled there. The captured barque at La Tasca was refloated and armed. It was then put under the command of Robert Searle.

Over the next few days, they seized and looted the islands of Perico, Taboga, Taboguila, and other small islands near the coast. At Taboga, they seized more boats. The privateers soon had a small fleet of three armed barques and a brigantine (another type of sailing ship). They were then able to raid the Pearl Islands and nearby coastal towns. This effort brought in most of the silver during the expedition. Many citizens hiding on the islands were taken prisoner along with their valuables.

Morgan claimed to have taken as many as 3,000 prisoners. This number included those from the battle until the end of the looting. Each company was to bring mules to load the treasure. They would take it to "Venta de Cruces" to return via the Río Chagres. Much of Panama's wealth was destroyed by the fire. Some had been moved by ships before the privateers arrived.

After almost three weeks in Panama, Morgan was ready to return. They had collected all the loot they could. It took up a lot of space. Meanwhile, news reached the Viceroy of Peru, Pedro de Castro. He heard about Morgan's capture of Chagres and his march to Panama. De Castro had already prepared for a possible English attack. He sent an expedition of eighteen ships and nearly 3,000 troops. However, de Castro arrived in Panama too late. Morgan had already left the city.

Returning to Jamaica

On February 24, the privateers began their march back. They had 175 pack animals loaded with treasure. Before leaving, the English disabled the remaining guns and destroyed the small fort facing the sea.

On their way back to Venta de Cruces, they also brought 600 prisoners of all ages. Most of them were ransomed before they reached Chagres. This number grew by another 150 as they captured more stragglers. After a few days, Morgan arrived at Venta de Cruces without problems. He waited for the prisoners' ransom to be delivered. He demanded about 150 Pesos per person. If not paid, he threatened to send them to Jamaica. Most of the ransom was paid. After nine days, all prisoners were released. During that time, the privateers gathered supplies for the return journey, which was much easier. As they set off, they noticed the Chagres River was high enough for boats to sail all the way to San Lorenzo. Morgan ordered his entire army to be searched, including himself. This was to make sure no one was hiding any valuable items from the shared treasure.

The value of the treasure Morgan collected ranged from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos. This doesn't include precious stones that were sold later. The loot was much larger than what was taken at Portobello two years earlier. However, because Morgan had such a large army, the amount each privateer received was relatively low. After money was set aside for the wounded, doctors, carpenters, and officers, an ordinary privateer received 80 pieces of eight. Many complained this was too little. This caused some unhappiness. Some accounts, especially in Exquemelin's writings, accused Morgan of taking most of the treasure.

Morgan arrived at San Lorenzo after only two days of travel along the Chagres. There, he tried to demand a ransom for the fort. But when it was clear no money would come, he ordered the town and its defenses destroyed. The French used explosives to complete the demolition. Morgan then gathered the fleet and headed back to Jamaica. The French, with eight ships, returned to Tortuga. Morgan, with four ships and about 500 men, returned to Port Royal in early March. He brought the news of his victory. But he was then told that the Madrid peace treaty had already been signed and approved.

What Happened Next

The attack shocked the Spanish empire. Many settlements and towns remained on edge, even with the peace. Morgan's actions helped force the Spanish to give up their exclusive rights in the Americas. Morgan did not know that England and Spain had signed a peace treaty the previous September. He only received news from the Governor of Cartagena.

By the time news of the peace reached Jamaica, Panama had already burned. The sacking of Panama marked the end of government-sponsored piracy. However, the destruction so soon after the treaty caused a crisis between England and Spain. In the treaty, Spain recognized England's colonies in the Americas. This was a big concession. In earlier treaties, Spain always said the New World west of Brazil belonged only to them. For this recognition, Charles II agreed to stop privateering in the Caribbean. He also agreed to stop issuing Letters of Marque. In return, Spain agreed to allow English ships freedom of movement. The generous terms of the treaty for England put Morgan in a difficult spot.

The Spanish ambassador protested strongly to Lord Arlington. Charles II formally apologized. He pretended he didn't know about the attack. But Spain demanded that Morgan be punished. Charles also sent a new Governor, Thomas Lynch. Lynch was ordered to arrest both Modyford and Morgan. They were to be sent in chains to London to be tried for piracy. Both were supposed to be held in the Tower of London. But instead, Morgan was welcomed as a hero by the public in London.

Morgan was free during his time in London. The political mood changed in his favor. The Earl of Arlington asked him to write a report for the King. This report was about how to improve Jamaica's defenses. Morgan was never charged with a crime. He gave informal evidence to the Lords of Trade and Plantations. He proved he didn't know about the Treaty of Madrid before his attack on Panama. He was found not guilty. He was "released" and lived comfortably in London for three years. In 1675, he returned to the Caribbean as Deputy Governor of Jamaica. He was knighted the same year. He then retired from privateering and married the daughter of one of the island's leading officers.

The privateers themselves were disappointed with their share of the treasure. Many went their separate ways. Many didn't return to Jamaica until July. Even then, they didn't stay long. Most wanted to continue their piratical lifestyle. But instead, they ended up on the Mosquito Coast. There, they started cutting logwood for dye. This itself would later become a debate between England and Spain about whether it was a legal job.

Later in 1670, rumors of a foreign invasion spread. The viceroy of Peru, De Castro, ordered all Pacific ports to be fully prepared. Don Pérez de Guzmán was dismissed for the second time by the viceroy. He was imprisoned in Lima for the defeat and held responsible for the destruction. He was cleared of charges later. He returned to Madrid but died a heartbroken man three years later.

The burning of Panama was very costly for the Spanish. It caused an estimated 11 to 18 million pesos in damage. The loss was a huge failure for their system. A part of the rebuilding costs had to be paid by the Spanish Crown. When the Spanish citizens returned to a ruined Panama, they only found the convent and a few small houses that had escaped destruction. Disease then spread among the residents. About 3,000 out of 10,000 people died in the following months.

Panama was never rebuilt in the same spot. A new settlement was built in 1673. It was supervised by the new Governor, Antonio Fernández de Córdoba. This new location was about 5 miles (8 km) southwest of the original. It soon merged with the older city. This area is now known as the Casco Viejo (Old Quarter) of the city. The ruins of the old city are still visible. It has been a World Heritage Site since 1997.

Ruins of Panama Viejo (Old Panama)

Legacy of the Expedition

- Morgan's ship, the Satisfaction, lies off Lajas reef where it sank. A team from Texas State University discovered the wreck in July 2011.

- In 2014, this expedition inspired the company Diageo, which owns Captain Morgan rum. They launched a special 'Captain Morgan 1671' limited edition drink.

See Also

- Francis Drake's expedition of 1572–1573

- Drake's Assault on Panama