Herbert Vivian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Herbert Vivian

|

|

|---|---|

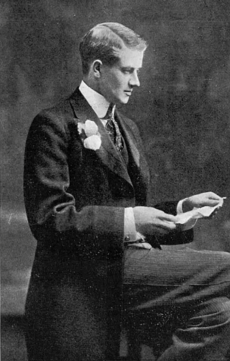

Herbert Vivian in 1905

|

|

| Born | 3 April 1865 |

| Died | 18 April 1940 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

| Known for | Neo-Jacobite Revival |

| Partner(s) | Maud Mary Simpson (1893–1896) Olive Walton (1897 – c. 1927) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Herbert Vivian (born April 3, 1865 – died April 18, 1940) was an English journalist, author, and newspaper owner. He was friends with important figures like Lord Randolph Churchill and later his son, Winston Churchill. Vivian was known for supporting Irish Home Rule, which meant Ireland having more control over its own government.

In the 1890s, he became a leader of the Neo-Jacobite Revival. This was a movement that wanted to bring back the House of Stuart royal family to the British throne instead of the current parliamentary system. Later in his life, in the 1920s, he supported fascism, a political idea where the government has total control. Vivian wrote several books, including a novel called The Green Bay Tree. He was also very interested in the Balkans region and wrote influential books about Serbia.

Contents

- Early Life and School Days

- University and New Friends

- Working for Wilfrid Blunt

- Herbert Vivian and Oscar Wilde

- Starting Newspapers and the Neo-Jacobite Movement

- Writing and Travel

- Trying for Parliament

- Support for Fascism

- His Political Ideas

- How People See Him Today

- Later Life and Honors

- Works

- Images for kids

Early Life and School Days

Herbert Vivian was born in Chichester, England, on April 3, 1865. He was the only son of Francis Henry and Margaret Vivian. His grandfather, John Vivian, was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Truro.

Herbert went to Harrow School from 1879 to 1883. When he was 14, he met Thomas Hughes, who wrote the famous book Tom Brown's School Days. This meeting had a big impact on young Herbert.

In 1881, his grandfather introduced him to Thomas Bayley Potter, an MP for Rochdale. Potter was impressed by Herbert and often took him to the Parliament building during school holidays. There, Herbert met many MPs, including Lord Randolph Churchill. Churchill inspired Herbert to support "Tory democracy," which was a political idea that aimed to help ordinary people while still being conservative. Herbert and Lord Randolph Churchill wrote letters to each other for many years. Herbert later became friends with Lord Randolph's son, Winston Churchill, who would become a famous Prime Minister.

University and New Friends

Herbert Vivian studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and graduated in 1886 with a degree in history. While at Cambridge, he was president of the University Carlton Club, a student political group. He invited Lord Randolph Churchill to be its president.

Herbert used his connections to meet important people. He even met Nubar Pasha, the first Prime Minister of Egypt, in Switzerland. After talking politics with Pasha, he reported back to Churchill. Churchill then introduced Herbert to Charles Russell, who became a very important judge in England. They became good friends.

At Cambridge, Herbert also made friends with students who became famous politicians and businessmen. These included Austen Chamberlain and Leopold Maxse, who later edited an important magazine called National Review. Another friend was Ernest Debenham, who went on to lead the famous Debenhams department store.

Working for Wilfrid Blunt

In 1886, Herbert and his friend Austen Chamberlain invited Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, a writer and poet, to speak at Cambridge about Irish Home Rule. This was a movement that wanted Ireland to have its own government. Herbert and Blunt became friends.

Later that year, Herbert became Blunt's private secretary. He spent many weekends at Blunt's home, Crabbet Park, and continued to work for him after graduating from university. Through this job, he met many influential politicians.

Blunt was a strong supporter of Irish Home Rule. In 1887, Lord Randolph Churchill advised Herbert to stop working for Blunt, but Herbert didn't listen. Blunt also became interested in the Jacobite cause, which was the idea of bringing back the old House of Stuart royal family to the British throne. This idea became a lifelong passion for Herbert.

In late 1887, Herbert left the Conservative Party and joined a group that supported Irish Home Rule. He even toured Ireland with important Irish politicians. In 1887, Blunt was arrested and imprisoned for giving a speech that had been banned. While Blunt was in prison, Herbert worked to help him run for Parliament in the 1888 Deptford by-election. Blunt lost the election, but he and Herbert were later asked to run again for Deptford, though Blunt's interests had moved on by the time the next election came.

Herbert Vivian and Oscar Wilde

In the late 1880s, Herbert Vivian was friends with the famous writer Oscar Wilde. They often had dinner together. Herbert later wrote about a funny conversation he claimed to have heard between Wilde and another artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler said something witty, and Wilde said he wished he had said it. Whistler then replied, "You will, Oscar, you will," suggesting Wilde often took other people's clever sayings as his own.

In 1889, Herbert included this story in an article. Wilde saw this as a betrayal and it caused a big argument between Wilde and Whistler. It also ended the friendship between Wilde and Herbert. After this, Herbert and Whistler became friends and wrote letters to each other for many years.

Starting Newspapers and the Neo-Jacobite Movement

The late 1880s and 1890s saw a rise in the Neo-Jacobite Revival in Britain. This was a movement that wanted to bring back the Stuart royal family. In 1886, a group called the Order of the White Rose was founded, supporting Jacobitism and independence for places like Ireland and Scotland. Herbert Vivian was a member.

In 1890, Herbert and a friend named Stuart Richard Erskine started a weekly newspaper called The Whirlwind, A Lively and Eccentric Newspaper. Herbert was the editor. The newspaper was known for its illustrations by famous artists like Whistler and Walter Sickert. The Whirlwind supported an individualist and Jacobite political view.

However, The Whirlwind also published very strong and controversial opinions that were widely criticized. Herbert used his role as editor to promote his ideas. The newspaper stopped publishing in early 1891.

In 1891, the Order of the White Rose split. Herbert and Erskine wanted a more active political group. They founded a new group called the Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland. This League worked to promote Jacobitism more widely than it had been seen since the 1700s.

The League often organized protests. In late 1892, they asked for permission to place wreaths at the statue of King Charles I in London on the anniversary of his execution. The Prime Minister said no. But Herbert and other members tried to lay the wreaths anyway on January 30, 1893. Police tried to stop them, but after a discussion, Herbert and his group were allowed to finish. This event got a lot of attention in the newspapers.

Herbert left the Jacobite League in August 1893, but he continued to support Jacobite political ideas very strongly. In 1895, he edited another newspaper called The White Cockade, which also promoted the Jacobite cause, but it was not very successful. By 1897, Herbert was the President of the Legitimist Club, another Jacobite group. He continued to use similar tactics, like laying wreaths and getting press coverage, to promote his cause.

Writing and Travel

After leaving the Jacobite League in 1893, Herbert Vivian became a travel writer for Pearson's Weekly. He also launched and edited a new weekly paper called Give and Take.

From 1898 to 1900, he worked as a travel journalist for the Morning Post and then for the new Daily Express. In 1901 and 1902, he created a magazine called The Rambler. Herbert also wrote several novels, some using different names, which received mixed reviews.

His most famous travel book was Servia: The Poor Man's Paradise (1897), which was quoted widely in newspapers. In 1901, he wrote a book with his wife, Olive, about European religious traditions.

In 1903, Herbert wrote about Serbia again for the English Illustrated Magazine. He followed this with another book, The Servian Tragedy: With Some Impressions of Macedonia (1904). This book described a major political event in Serbia where the royal family was overthrown. Some reviews praised his knowledge of the country, while others said it lacked strong evidence.

Herbert was friends with Winston Churchill and met him several times in the early 1900s. In 1905, Herbert published the first interview ever given by Churchill, which appeared in The Pall Mall Magazine and got a lot of attention. He also interviewed David Lloyd George, another important politician.

Herbert continued his strong interest in the Balkan countries. In 1907, he was involved in a plan to put Prince Arthur of Connaught on the throne of Serbia. A year later, the government of Montenegro considered making him their representative in London.

In 1908, Herbert proposed a gambling "system" for roulette in The Evening Standard. However, this system was later shown to be incorrect by Hiram Maxim, a famous inventor.

During the First World War, Herbert continued to publish books, including Italy at War in 1917, which was mostly a travel book. He tried to join the government's Ministry of Information but was not accepted. He returned to the Daily Express as a travel writer in 1918.

In the 1920s, Herbert worked as a travel writer for various newspapers. In 1927, he wrote Secret Societies Old and New, which received mixed reviews.

In 1932, Herbert wrote The Life of the Emperor Charles of Austria, the first biography of Emperor Charles published in English. He also continued to write about the Balkans, including an article on tensions in Yugoslavia in 1933. Herbert Vivian's writings were well-known during his lifetime and are still referenced today.

Trying for Parliament

Herbert Vivian tried to become a Member of Parliament several times. In 1889, he wanted to run in an election in Dover but later claimed he was prevented from doing so.

In April 1891, he announced he was running in the East Bradford area for his "Individualist Party," which he was the only member of! He later claimed to be the Labour candidate, but this was denied by local labor groups. He lost the election in 1892.

In 1895, he ran for the North Huntingdonshire area, specifically promoting his Jacobite ideas. He lost that election too.

Even after these failures, Herbert tried again in the 20th century. He was interested in the Deptford area, where he had helped Wilfrid Blunt years earlier. He started campaigning there in late 1903. In 1904, he joined the Liberal Party, following his friend Winston Churchill. He was chosen as a Liberal candidate for the 1906 election, and Churchill even spoke to support him. However, Herbert faced strong opposition and received only a small number of votes, losing badly.

In 1908, Herbert considered running for another seat after the former Prime Minister died. He again expressed his ideas about bringing back the Stuart royal family. In the end, he did not run.

Support for Fascism

In 1920, Herbert Vivian met Benito Mussolini and Gabriele D'Annunzio in Italy. He became a strong admirer of fascism, especially Italian Fascism. Fascism is a political system where the government has complete control over people's lives and often promotes strong nationalism.

In May 1929, Herbert and another person founded the Royalist International. This group aimed to stop the spread of communism and bring back the Italian monarchy, but it also clearly supported fascism. Herbert was the group's General Secretary and edited its publication.

In 1936, Herbert published Fascist Italy, where he openly showed his admiration for the Italian fascist government. This book received very negative reviews. One newspaper called it "crude propaganda" and said it should not be taken seriously.

His Political Ideas

Herbert Vivian's political ideas changed throughout his life. At different times, he supported conservative ideas, free-trade liberalism, and openly supported fascism. It seemed he was often more interested in how power worked and how to give persuasive speeches than in sticking to the same policies.

He was known for his "extreme monarchist views" throughout his life, meaning he strongly believed in kings and queens ruling. He became against democracy. In his 1933 book Kings in Waiting, he wrote that "Democracy, liberty, and prosperity had been the mirages that had attracted the nations to their shambles," showing his strong anti-democracy stance.

He was also a prominent supporter of Serbia and an early believer in a "Greater Serbia," which meant a larger Serbian state that included parts of Macedonia.

How People See Him Today

Herbert Vivian's books and articles about Serbia are still often quoted in modern history books about the region. Experts say his book Servia: A Poor Man's Paradise gave a detailed and fairly objective picture of Serbia's political system and economy at the time. Some historians believe he greatly influenced how the British viewed the Balkans after the First World War.

Although his Neo-Jacobite ideas are mostly forgotten today, his wreath-laying event in 1893 earned him the nickname "political maverick." One historian said the event got a lot of attention, even though the Jacobite cause was no longer very important, because it showed one person's fight against government rules.

Later Life and Honors

In 1897, Herbert Vivian married Olive Walton, whose father invented linoleum. Herbert and Olive were well-known in London society after the First World War.

Herbert Vivian received honors from other countries. He was made a Knight of the Royal Serbian Order of Takovo in 1902 and a Commander of the Royal Montenegrin Order of Danilo in 1910.

Herbert Vivian died on April 18, 1940, in Cornwall, England.

Works

- The Green Bay Tree (1894), with William Henry Wilkins

- Servia: The Poor Man's Paradise (1897)

- The Master Sinner (1898)

- The Servian Tragedy: With Some Impressions of Macedonia (1904)

- The Master of the Ceremonies (1907)

- The Life of the Emperor Charles of Austria (1932)

- Kings in Waiting (1933)

- Fascist Italy (1936)

Some books are commonly thought to be by Vivian, but some sources say another author wrote them:

- The Master of the Ceremonies (published under a pseudonym)

- The Master Sinner (published anonymously)

- The Master of the Ceremonies (published anonymously)

Images for kids

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |