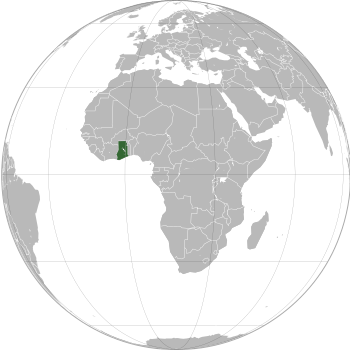

History of Ghana facts for kids

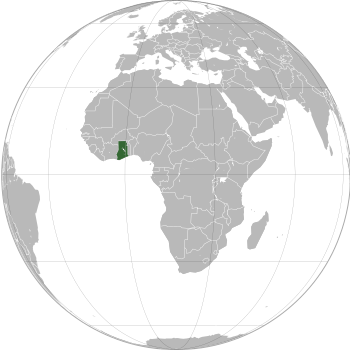

The country we know today as Ghana has a long and interesting history. It was named after the ancient Ghana Empire, which was a powerful kingdom far to the north. This old empire was famous for its gold and trade. After it broke up around 1076, many groups moved south.

Over time, different kingdoms formed in the area that is now modern Ghana. The Akan people created states like the Bono state. The Mole-Dagbon people also formed early kingdoms. These groups built strong societies with their own rulers and traditions. The Ashanti kingdom, especially, grew into a powerful empire with a well-organized government centered in Kumasi.

Contents

Early History of Ghana's Kingdoms

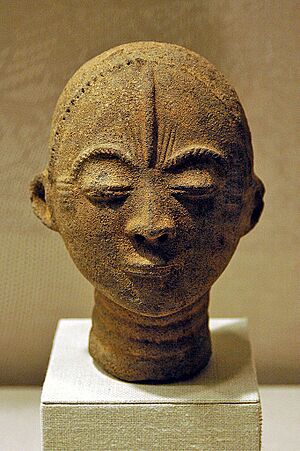

People have lived in what is now Ghana for thousands of years. Evidence shows that communities existed along the coast around 2000 BC. Central Ghana was also settled about 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.

The word Ghana originally referred to the king of the ancient empire. Arab historians wrote about this kingdom, describing its rulers as very wealthy. They were known for their gold and their trading skills. This wealth attracted merchants from North Africa.

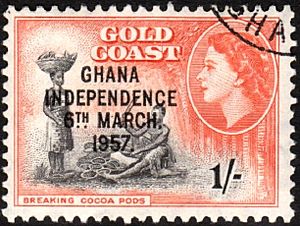

Even though the ancient Ghana Empire was far away, its name and fame lived on. When the Gold Coast became the first black African nation to gain independence in 1957, its leaders chose the name Ghana. This honored the old empire's reputation for wealth and trade in gold.

Trade routes that connected the western Sudan (an area north of modern Ghana) also helped new states grow in the forest zone of southern Ghana. New crops from other parts of the world, like bananas and cassava, helped people settle in the forest. By the 16th century, European explorers noted the rich gold states like Akan and Twifu.

The Mole-Dagbon kingdoms, founded by Naa Gbewaa, were among the earliest in modern Ghana. These included the Kingdom of Dagbon, Gmamprugu, and Nanung. They resisted slavery and colonization, preferring to trade goods instead of people. Islam also influenced these northern kingdoms through trade.

The Dagomba Kingdom's Beginnings

The Dagomba states were some of the first kingdoms in Ghana, starting around the 11th century. By the late 16th century, they were well-established. Even though their rulers were not always Muslim, they welcomed Muslim scribes and healers. This helped Islam spread in the northern parts of Ghana through merchants and religious leaders.

Between the Dagomba state and the Mossi Kingdoms (in present-day Burkina Faso), lived groups like the Kassena farmers. They lived in smaller, kinship-based societies. Trade routes passed through their lands, bringing Islamic influence and sometimes conflict with more powerful neighbors.

The Bono State's Cultural Impact

The Bono State, or Bonoman, was a trading kingdom founded by the Bono people around the 11th century. They were a Twi-speaking Akan group. This kingdom is seen as the origin for many Akan subgroups who later moved to create new states, often looking for gold.

The gold trade, which boomed in Bonoman in the 12th century, was key to the Akan people's power and wealth. Many parts of Akan culture, like the use of umbrellas for kings, national swords, stools (thrones), goldsmithing, and Kente cloth weaving, came from the Bono State.

Rise of the Ashanti Empire

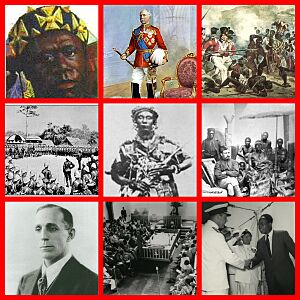

Under Chief Oti Akenten (around 1630–1660), the Ashanti began to expand their influence. They won battles against nearby Akan states, forming alliances. At the end of the 17th century, Osei Tutu became the Asantehene (king of Ashanti). He turned the group of Ashanti states into a powerful empire with its capital at Kumasi. This brought strong, central rule.

Osei Tutu was greatly influenced by the high priest Anokye. Legend says Anokye made a golden stool appear from the sky. This Golden Stool became a symbol of unity for all the allied Ashanti states. It is still a very important national symbol today.

Osei Tutu allowed newly conquered areas to keep their own customs and chiefs. These chiefs even got seats on the Ashanti state council. This made it easier for different Akan groups to join the confederation. Each smaller state kept some self-rule, but they all worked together on important national matters.

By the mid-18th century, the Ashanti Empire was very organized. Wars of expansion under Opoku Ware I (Osei Tutu's successor) brought northern states like Dagomba under Ashanti influence. By the 1820s, Ashanti rulers had expanded south, leading to contact, and sometimes conflict, with the coastal Fante and European traders.

Early European Contact and Trade

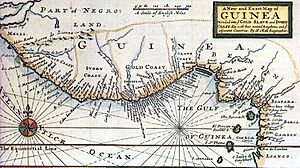

When Europeans first arrived in the late 15th century, many local groups were still settling their territories. Initially, the Gold Coast did not export slaves. Instead, the Akan people bought slaves from Portuguese traders to help with labor for their growing states.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive, reaching the Gold Coast by 1471. They were interested in gold, ivory, and pepper. In 1482, they built their first permanent trading post, São Jorge da Mina (later Elmina Castle), to protect their trade. This castle still stands today.

The Portuguese controlled trade for over a century. By 1598, the Dutch began trading and built their own forts. They captured Elmina Castle from the Portuguese in 1637. Other European traders, like the English, Danes, and Swedes, joined in by the mid-17th century. The coast became dotted with over 30 forts and castles. These were built to protect European interests from rivals and pirates. Europeans also formed alliances with local leaders, sometimes getting involved in local conflicts.

Forts were often fought over, sold, or abandoned. The Dutch West India Company was active throughout the 18th century. The British African Company of Merchants, founded in 1750, also built and managed forts. The Swedes and Prussians had short-lived ventures. The Danes left in 1850. By the late 19th century, the British owned all Dutch coastal forts, becoming the main European power.

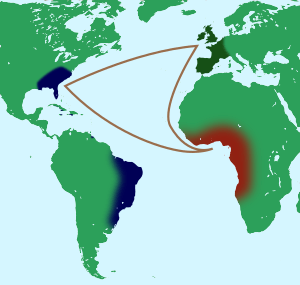

In the late 17th century, changes in local societies led to a shift. The Gold Coast went from importing slaves to becoming a major exporter of slaves.

Some historians say that wars were not just for capturing slaves. For example, the Ashanti fought to control territories, collect tribute from other kingdoms, and secure trade routes to the coast.

Africans themselves controlled the supply of slaves to the Gold Coast. Many rulers and merchants were involved in the slave trade. Slaves were also brought from other regions and sold to middlemen.

The slave trade had a huge impact on West Africa. Many Africans died during wars, bandit attacks, or while waiting to be shipped. All nations involved in West Africa participated in the slave trade. Relations between Europeans and local people were often tense, leading to clashes. Diseases caused many European deaths, but the profits kept them coming.

The movement to end slavery, called abolitionism, grew slowly. Some religious leaders spoke against slavery early on, but major Christian groups did little at first. The Quakers were against slavery from 1727. Later, the Danes, Swedes, and Dutch stopped trading slaves.

In 1807, Britain used its navy to outlaw the slave trade for its citizens. They also tried to stop the international slave trade. This helped reduce the external slave trade. The United States outlawed slave importation in 1808. However, these efforts didn't fully succeed until the 1860s because of the demand for labor in the New World.

Some historians, like Eric Williams, argue that Europe ended the slave trade because it became less profitable due to the Industrial Revolution. He suggested that new machines, the need for raw materials, and competition for markets led to the end of the human trade. Other scholars believe that humanitarian concerns, along with economic factors, were important in ending the African slave trade.

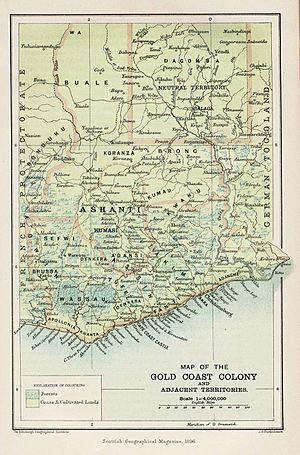

British Gold Coast Colony

By the late 19th century, only the Dutch and British remained. After the Dutch left in 1874, Britain made the Gold Coast a protectorate, a British Crown Colony. The British gradually gained control over the area. This led to conflicts, including the four Anglo-Ashanti Wars.

By the early 19th century, the British owned most of the forts along the coast. Two main reasons led to British rule: the Ashanti wars, which caused instability and hurt trade, and Britain's focus on ending the slave trade.

During the 19th century, Ashanti, the most powerful state, tried to expand its rule and protect its trade. Ashanti invasions of coastal regions happened in 1807, 1811, and 1814. These invasions disrupted trade in gold, timber, and palm oil, and threatened European forts. European authorities had to deal with Ashanti. In 1817, the African Company of Merchants signed a treaty recognizing Ashanti claims to coastal areas.

Coastal people, especially the Fante and those in Accra, relied on British protection against Ashanti attacks. But the merchant companies couldn't provide enough security. The British Crown took over the forts in 1821, putting them under the governor of Sierra Leone, Charles MacCarthy. MacCarthy wanted to bring peace and end the slave trade by encouraging coastal people to oppose Ashanti. However, fighting continued. In 1823, the First Anglo-Ashanti War began, and MacCarthy was killed in 1824.

When the British government gave control back to the African Company of Merchants in the late 1820s, problems with Ashanti continued. Ashanti felt the British didn't control their coastal allies. MacCarthy's actions made Ashanti believe Europeans didn't respect them.

In 1830, Captain George Maclean became president of a local council of merchants. He achieved a peace treaty with Ashanti in 1831. Maclean also held court in Cape Coast, punishing those who disturbed the peace. From 1830 to 1843, there were no conflicts with Ashanti, and trade grew a lot.

Maclean's work led a parliamentary committee to recommend that the British government permanently manage its settlements. They also suggested negotiating treaties with local chiefs. This happened in 1843, and Commander H. Worsley Hill became the first governor. Hill negotiated the Bond of 1844 with Fante and other chiefs. This document made serious crimes, like murder, subject to British law. It became the legal basis for British colonization of the coastal area.

More states signed the Bond, and British influence grew. The British seemed to promise protection for coastal areas, creating an informal protectorate. As responsibilities grew, the Gold Coast administration was separated from Sierra Leone in 1850.

In 1852, local chiefs and elders met in Cape Coast to discuss raising money. With the governor's approval, they formed a legislative assembly. This assembly was meant to be a permanent part of the protectorate's government, but it couldn't pass laws or levy taxes without the people's consent.

The Second Anglo-Ashanti War happened from 1863 to 1864. In 1872, Britain bought Elmina Castle, the last Dutch fort. The Ashanti, who saw the Dutch as allies, lost their last trade route to the sea. To prevent this, Ashanti invaded the coast in 1873. They faced well-trained British forces and had to retreat. Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley refused to negotiate. To end the Ashanti problem, the British invaded Ashanti in January 1874, occupying and burning Kumasi. This was the Third Anglo-Ashanti War.

The peace treaty of 1875 forced Ashanti to give up claims to many southern territories. They also had to keep the road to Kumasi open for trade. Ashanti power then declined. Subject territories broke away, and protected regions joined British rule. However, the Ashanti spirit was not fully broken. In 1896, the British sent another expedition, occupied Kumasi again, and made Ashanti a protectorate. This was the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War. The position of Asantehene was abolished, and Prempeh I was exiled. A British official was placed in Kumasi.

The Ashanti federation accepted these terms reluctantly. In 1900, the Ashanti rebelled again in the War of the Golden Stool but were defeated in 1901. On September 26, 1901, Britain officially made Ashanti a Crown Colony. It was placed under the Gold Coast governor. With Ashanti subdued, British colonization of the region became complete.

Protestant Missions' Influence

In the 19th century, Protestant nations like Britain believed they had a duty to "civilize" people. Along with business and national pride, spreading Christianity was a strong reason for imperialism. Missionaries focused on ending the slave trade and traditional slavery. The British Royal Navy helped stop transoceanic slave ships.

The first missionaries to pre-colonial Ghana were from Switzerland's Basel Mission. They had limited funds and used child labor, who were students in mission schools. These children split their time between learning and unpaid work. The Basel Mission tried to improve the harsh conditions of child labor and debt slavery.

British Colonial Rule: Gold Coast Era

Conflicts between Ashanti and Fante helped British influence grow. The Fante states, worried about Ashanti, signed the Bond of 1844. This allowed the British to take over legal authority from African courts. On July 24, 1874, the British declared the Gold Coast Colony, extending inland from the coast. Coastal people didn't resist much, partly because the British didn't claim land rights.

In 1896, British forces invaded Ashanti and removed the Asantehene, Prempeh I. A British official replaced him in Kumasi. British influence now included Ashanti. However, in 1900, British Governor Hodgson demanded the "Golden Stool," a symbol of Ashanti rule. This led to the War of the Golden Stool against the British. The Ashanti were defeated again in 1901. The British then appointed a resident commissioner to Ashanti. Each Ashanti state was managed separately, reporting to the Gold Coast governor.

The British also became interested in the Northern Territories, north of Ashanti, to prevent French and German expansion. After 1896, they extended protection to these northern areas. In 1898 and 1899, European powers set the boundaries for the Northern Territories. The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast Protectorate was established on September 26, 1901. Unlike Ashanti, it was not annexed but placed under a resident commissioner, who reported to the Gold Coast Governor. The Governor ruled Ashanti and the Northern Territories by official announcements until 1946.

With the north under British control, the three areas—the Colony (coastal regions), Ashanti, and the Northern Territories—became one political unit, the Gold Coast. The borders of modern Ghana were finalized in May 1956. This happened when the people of the Volta region, then British Mandated Togoland, voted to join modern Ghana.

How the Colony Was Run

Beginning in 1850, the coastal regions were increasingly controlled by the British governor. He was helped by an Executive Council and a Legislative Council. The Executive Council was a small group of European officials who suggested laws and taxes. The Legislative Council included these officials and other members, initially from British businesses. After 1900, three chiefs and three other Africans joined the Legislative Council.

The colonial government gradually centralized control over local services. Traditional states still played a role in local administration. Village councils of chiefs and elders handled local needs, like law and order. Chiefs ruled with the consent of their people.

British authorities used "indirect rule." This meant traditional chiefs kept power but followed instructions from European supervisors. Indirect rule was cheaper and reduced local opposition. However, it made chiefs look to the capital, Accra, instead of their people for decisions. Many chiefs, rewarded by the British, saw themselves as a ruling class. This system didn't give opportunities to educated young Ghanaians.

In 1925, provincial councils of chiefs were set up. The 1927 Native Administration Ordinance clarified the chiefs' powers. In 1935, the Native Authorities Ordinance combined central and local governments. New native authorities, appointed by the governor, had broad local powers under central government supervision. These reforms were not popular. Some Ghanaians felt they increased chiefs' power at the expense of local people, preventing popular participation in government.

Economic and Social Growth

British rule in the Gold Coast during the 20th century brought big improvements. Transportation and railroads got much better. Poverty decreased, and Ghanaian farmers did well. New crops were introduced, like coffee. The most important new crop was cocoa, which came from the New World. Tetteh Quashie, a blacksmith, brought cocoa to the Gold Coast in 1879. Cocoa farming became very popular in eastern Gold Coast.

In 1891, the Gold Coast exported only 80 pounds of cocoa. By the 1920s, exports passed 200,000 tons, worth £4.7 million. By 1928, it reached £11.7 million. Cocoa production became a huge part of the Gold Coast's economy.

Studies show that living standards improved greatly in the early 20th century when cocoa farming took off. Africans themselves were the main drivers of this economic change. African farmers were willing to take risks with cocoa, outperforming European planters.

The colony also earned money from timber and gold exports. This money funded improvements in infrastructure and social services. A more advanced education system than anywhere else in West Africa also developed. This British-style education created a new Ghanaian elite. Missionary schools led to secondary schools and the country's first higher learning institute.

Many improvements in the early 20th century are credited to Gordon Guggisberg, governor from 1919 to 1927. He proposed a ten-year development plan, focusing first on transportation, then water supply, drainage, hydroelectric projects, and more. Guggisberg also aimed to fill half of the colony's technical jobs with trained Africans. His plan was the most ambitious in West Africa at the time.

The colony helped Britain in both World War I and World War II. After the wars, inflation and instability made it hard for returning soldiers. Their war service broadened their views, making it difficult to return to their old, limited roles. This led to growing discontent.

Rise of Nationalism and End of Colonial Rule

As Ghana's economy grew, so did education. In 1890, there were only 5 government schools and 49 mission schools, with 5,000 students. By 1950, there were 3,000 schools with 279,000 children attending. This meant 43.6% of school-aged children were in school.

By the end of World War II, the Gold Coast was the richest and most educated territory in West Africa. Power slowly shifted from the governor to Ghanaians. This was due to a strong spirit of nationalism, which eventually led to independence. National awareness grew quickly after World War II, with ex-soldiers, urban workers, and traders supporting the educated minority.

Early Signs of Ghanaian Nationalism

By the late 19th century, educated Africans found the political system unfair. The governor had almost all power. In the 1890s, some educated coastal leaders formed the Aborigines' Rights Protection Society. They protested a land bill that threatened traditional land ownership. This protest helped start the political movement for independence.

In 1920, J. E. Casely Hayford, an African member of the Legislative Council, organized the National Congress of British West Africa. This group demanded many reforms for British West Africa. They sent a delegation to London, asking for elected representatives. This was the first time African intellectuals and nationalists showed political unity. Although London didn't receive them, their actions gained support among the African elite.

These nationalists said they were loyal to the British Crown. They just wanted British political and social practices extended to Africans. Leaders like Africanus Horton and John Mensah Sarbah gave the movement an elite feel until the late 1940s.

The constitution of April 8, 1925, created provincial councils of paramount chiefs. These councils elected six chiefs to the Legislative Council. However, the British still had a majority, and the council's powers were only advisory. Governor Guggisberg wanted to protect British interests. He gave Africans a limited voice, but by only allowing chiefs, he created a divide between chiefs and educated people. Intellectuals felt the chiefs were too controlled by the British. By the mid-1930s, chiefs and intellectuals began to work together.

People continued to demand more representation. African-owned newspapers helped spread this discontent. By the 1930s, six newspapers were being published. In 1943, two more African members were added to the Executive Council. Changes to the Legislative Council came after the British Labour Party won elections after the war.

The new Gold Coast constitution of March 29, 1946 (the Burns constitution), was a bold step. For the first time, elected members were a majority in the Legislative Council. It had six official members, six nominated members, and eighteen elected members. However, the council still only had advisory powers. All executive power stayed with the governor. This constitution also included representatives from Ashanti for the first time.

Even with a Labour government, Britain still saw colonies as sources of raw materials for their struggling economy. Real power for Africans wasn't a priority until after the 1948 Accra Riots. These riots in Accra and other towns were about pensions for ex-soldiers, foreign control of the economy, housing shortages, and other problems.

With elected members in the majority, Ghana was politically mature for colonial Africa. But the constitution didn't grant full self-government. The governor still held executive power. The constitution, though welcomed, soon faced problems. World War II had just ended, and many Gold Coast veterans returned to a country with shortages, inflation, and unemployment. These veterans, along with unhappy urban workers, farmers (who disliked measures to cut diseased cocoa trees), and others, were ready for change.

Politics of Independence Movements

Political groups existed before, but the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), founded on August 4, 1947, was the first nationalist movement aiming for self-government "in the shortest possible time." Its leaders, known as The Big Six, were educated Ghanaians. They wanted educated people to replace chiefs on the Legislative Council. They also demanded respect and responsibility from the colonial administration. The UGCC criticized the government for not solving problems like unemployment and inflation.

Public dissatisfaction with the UGCC grew. On February 28, 1948, ex-servicemen demonstrated in Accra, leading to five days of violent disorder and looting. Rioting also spread to Kumasi and other towns. The Big Six, including Kwame Nkrumah, were imprisoned. These riots showed that the UGCC's gentle approach was not enough. Nkrumah broke with the UGCC in 1949 and formed his own Convention People's Party (CPP) on June 12, 1949.

Nkrumah, educated in the US and Britain, left the UGCC because he felt their efforts to gain self-government were too weak. Unlike the UGCC's call for self-government "in the shortest possible time," Nkrumah and the CPP demanded "self-government now." The CPP appealed to ordinary working people, farmers, youth, and market women. By June 1949, Nkrumah had a large following.

The constitution of January 1, 1951, came from the Coussey Committee, formed after the 1948 disturbances. It gave the Executive Council a majority of African ministers and created an assembly. This was a big step, but it still didn't give full self-government. Executive power remained British, and the legislature favored traditional interests.

With growing support, the CPP started a "Positive Action" campaign in early 1950, with strikes and nonviolent resistance. When some violence occurred on January 20, 1950, Nkrumah was arrested and jailed. This made him a hero. In the first elections for the Legislative Assembly (February 5–10, 1951), Nkrumah (still in jail) won a seat. The CPP won two-thirds of the votes, taking 34 of 38 elected seats. Nkrumah was released on February 11, 1951, and became "leader of government business," like a prime minister. His first term involved cooperation with the British governor. Over the next few years, the government became a full parliamentary system. Traditional African groups opposed these changes, but their opposition was ineffective against popular support for early independence.

On March 10, 1952, the new position of Prime minister was created, and Nkrumah was elected. The Executive Council became the Cabinet. The new constitution of May 5, 1954, ended the election of assembly members by tribal councils. All members were chosen by direct election. Only defense and foreign policy remained with the Governor. The elected assembly controlled almost all internal affairs. The CPP won 71 of 104 seats in the June 15, 1954, election.

The CPP wanted a centralized government, which faced strong opposition. After the June 15, 1954, election, the Ashanti-based National Liberation Movement (NLM) was formed. The NLM wanted a federal government with more power for regions. They criticized the CPP for being too dictatorial. The NLM worked with the Northern People's Party. When these regional parties left discussions on a new constitution, the CPP worried London might think Ghana wasn't ready for self-government.

However, the British constitutional adviser supported the CPP. The governor dissolved the assembly to test support for immediate independence. On May 11, 1956, the British agreed to grant independence if a "reasonable" majority of the new legislature requested it. New elections were held on July 17, 1956. The CPP won 57% of the votes. Due to fragmented opposition, the CPP won every seat in the south and enough in Ashanti, the Northern Territories, and Trans-Volta to get a two-thirds majority (72 of 104 seats).

On May 9, 1956, a vote was held to decide the future of British Togoland. This area had been linked to the Gold Coast since 1919. A majority (58%) voted to join, and the area became part of Ghana. However, the Ewe people (42%) in British Togoland strongly opposed this.

Ghana's Independence Achieved in 1957

In 1945, a Pan-African Congress was held in Manchester to promote Pan-African ideas. Nkrumah, Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria), and I. T. A. Wallace-Johnson (Sierra Leone) attended. The independence of India and Pakistan fueled this desire. There was also a rejection of some African cultural aspects. External forces like W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey (Afro-Jamaican) also raised Pan-African awareness.

Sir Alan Burns' 1946 constitution created a new legislative council. It had the Governor as President, 6 government officials, 6 nominated members, and 18 elected members. The executive council only advised the governor.

These forces led Dr. J. B. Danquah to form the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) in 1947. Nkrumah was invited to be its general secretary. Other officers included George Alfred Grant, Edward Akufo-Addo, and William Ofori Atta. Their goal was Ghana's independence. They rejected the Burns constitution and wanted changes. It gave a voice to chiefs and tribal councils by creating regional assemblies.

The CPP's victory in 1951 led to five years of shared power with the British. The economy thrived due to high global demand and rising cocoa prices. The Cocoa Marketing Board used its profits for infrastructure development. There was a major expansion of schooling and modern projects, like the new industrial city at Tema. Nkrumah supported organizations like the Young Pioneers and Builder's Brigades. These groups promoted patriotism and an ideal citizenship where duty to the state was primary.

Quick facts for kids

First Republic of Ghana

Ghana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1966 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Accra | ||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic (1960-1964) Presidential republic under a one-party state (1964-1966) |

||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1960–1966

|

Kwame Nkruma | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of Ghana | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

27 April 1960 | ||||||||

|

• 1964 Ghanaian constitutional referendum

|

31 January 1964 | ||||||||

|

• 1965 Ghanaian parliamentary election

|

1965 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

24 February 1966 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Ghana | ||||||||

On August 3, 1956, the new assembly asked for independence within the British Commonwealth. The British government agreed. On September 18, 1956, they set March 6, 1957, as the date for the Gold Coast, Ashanti, the Northern Territories, and British Togoland to become one independent country called Ghana. Kwame Nkrumah remained prime minister. Queen Elizabeth II was head of state, represented by Governor-General Sir Charles Noble Arden-Clarke. Ghana was a constitutional monarchy until 1960. After a vote, it became a Republic.

Nkrumah's Second Development Plan (1959–1964) focused on increasing productivity. As cocoa prices fell, budgets were cut. Workers were asked to make sacrifices. Nkrumah reduced the independence of labor unions. When strikes happened, he used the Preventive Detention Act to crack down.

Nkrumah believed that fast modernization of industries and communication was vital. He wanted the workforce to be fully African and educated. Expanding secondary schools and vocational programs became a high priority.

Challenges to Nkrumah's Rule

Nkrumah believed that rapid progress needed to be free from "reactionary politicians" and traditional chiefs who might work with Western powers. He felt that dissent was not to be tolerated. His government passed laws like the Deportation Act of 1957 and Detention Acts. His party, the CPP, became the only political organization. The Young Pioneer Movement educated youth in his ideas.

Nkrumah believed Ghana's independence was key to freeing all of Africa from colonial rule. He said, "the independence of Ghana would be meaningless unless it was tied to the total liberation of Africa." He wanted Ghanaians to "seek first the political kingdom."

Nkrumah dreamed of uniting Africa to protect its economic interests and stand strong against Cold War pressures. He encouraged revolutionary movements across Africa. The CIA believed Nkrumah's government funded and trained pro-socialist fighters. Hundreds of trainees were sent to countries like Rhodesia and Congo. Nkrumah thought a union of Ghana, Guinea, and Mali would inspire a United States of Africa. When criticized for focusing too much on Africa and wasting resources, he called his opponents short-sighted.

Protests Against Taxes

Nkrumah's development plans and Pan-African efforts were very expensive. In July 1961, the government introduced an austerity budget. This meant higher taxes and forced savings. Workers and farmers began to criticize these costs. Urban workers went on strike, one of many protests against government measures in 1961.

Nkrumah's calls to end corruption in government and the party also reduced public trust. A drop in the price paid to cocoa farmers by the government marketing board angered many, especially those who had been Nkrumah's main supporters.

Growing Opposition to Nkrumah

Nkrumah's strong control isolated other leaders. After opposition parties were banned, opponents came from within the CPP. Tawia Adamafio, an Accra politician, became minister of state for presidential affairs, a very important role. John Tettegah led the Trade Union Congress. However, their power came from Nkrumah.

By 1961, younger, more radical CPP members, led by Adamafio, gained influence. After a bomb attempt on Nkrumah's life in August 1962, Adamafio, Ako Adjei (foreign minister), and Cofie Crabbe were jailed. The first Ghanaian Commissioner of Police, E. R. T. Madjitey, was also removed.

The trial of the alleged plotters of the 1962 attack took center stage. When the court acquitted them, Nkrumah dismissed the chief justice, Sir Kobina Arku Korsah. Nkrumah then got parliament to allow a retrial. A new court, with a jury chosen by Nkrumah, found them guilty and sentenced them to death. These sentences were changed to twenty years in prison.

Corruption became a big problem. Money was diverted to political parties and Nkrumah's friends and family, hindering economic growth. New state companies became tools for favors and financial corruption. Civil servants doubled their salaries, and politicians bought support. Allegations of corruption in the ruling party and Nkrumah's personal finances hurt his government's legitimacy.

Political scientist Herbert H. Werlin noted the growing economic disaster. Ghana went from a foreign reserve of over $500 million at independence to a public debt of over $800 million by 1966. There was no foreign money to buy spare parts. Inflation was high, and unemployment was serious. While Ghana's economy grew by nearly 5% annually between 1955 and 1962, there was almost no growth by 1965. Personal spending per person dropped by about 15% between 1960 and 1966.

Nkrumah's Fall in 1966

In early 1964, after another national vote, Nkrumah changed the constitution to allow him to dismiss any judge. Ghana officially became a one-party state. An act of parliament ensured only one presidential candidate. Other parties were already outlawed. In June 1965, Nkrumah was re-elected president. Less than a year later, members of the National Liberation Council (NLC) overthrew the CPP government in a military coup on February 24, 1966. Nkrumah was in China at the time. He found asylum in Guinea and died in Romania in 1972.

Ghana Since 1966

The leaders of the 1966 military coup said they acted because Nkrumah's government was corrupt and dictatorial. They also said Nkrumah was too involved in African politics. They claimed the coup was nationalist, freeing the nation from Nkrumah's rule. Symbols and organizations linked to Nkrumah quickly disappeared.

Despite these changes, many problems remained, like ethnic divisions and economic burdens. Many Ghanaians believed that effective government was not possible with competing political parties. Some preferred nonpolitical leadership, even military rule. The problems of the Busia administration, the first elected government after Nkrumah, showed the challenges Ghana would continue to face. Some argue the coup was supported by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

The National Liberation Council (NLC), made of army and police officers, took power. They appointed a cabinet of civil servants and promised to restore democracy. This led to a representative assembly drafting a constitution for the Second Republic of Ghana. Political parties were allowed again in late 1968. In Ghana's 1969 elections, the first competitive national election since 1956, the main parties were the Progress Party (PP), led by Kofi Abrefa Busia, and the National Alliance of Liberals (NAL), led by Komla A. Gbedemah. The PP was supported by Nkrumah's old opponents: educated middle class and traditionalists. The NAL was seen as the CPP's right wing. The PP won 59% of the popular vote and 74% of seats.

Gbedemah was soon barred from his seat by a Supreme Court decision. He retired from politics, leaving the NAL without a strong leader. In October 1970, the NAL merged with other parties to form the Justice Party (JP) under Joseph Appiah. This created a southern bloc with support among the Ewe people and coastal cities.

PP leader Busia became prime minister in September 1970. After a short period, the electoral college chose Chief Justice Edward Akufo-Addo as president. He was a leading nationalist from the UGCC era and one of the judges Nkrumah dismissed.

All attention was on Prime Minister Busia and his government. Many expected a lot from the Busia administration, believing intellectuals would make better decisions for the nation. Ghanaians hoped their decisions would be for the common good, unlike Nkrumah's, which were seen as serving narrow party interests. The NLC had promised more democracy and freedom.

Two early actions by Busia's government were expelling many non-citizens and limiting foreign involvement in small businesses. These aimed to reduce unemployment due to the country's poor economy. These policies were popular because they pushed out foreigners, like Lebanese, Asians, and Nigerians, who were seen as unfairly controlling trade. However, many other Busia actions were not popular. His decision to charge university students for education, which had been free, was criticized for creating a class system. Some saw his currency devaluation and encouragement of foreign investment as conservative ideas that could harm Ghana's independence.

The opposition Justice Party's policies were similar to Busia's. Still, they stressed the importance of central government in economic development. They also focused on programs for urban workers. The ruling PP emphasized rural development to slow migration to cities and balance regional development. Both parties favored stopping payments on some foreign debts from Nkrumah's time. This idea grew popular as debt payments became harder to meet. Both parties also wanted a West African economic community.

Despite initial support, the Busia government fell to an army coup within 27 months. Neither ethnic nor class differences caused the overthrow. The main reasons were the country's ongoing economic problems, both from Nkrumah's high foreign debts and internal issues. The PP government inherited $580 million in debt. By 1971, this had grown to over $900 million with interest and short-term credits. A large internal debt also caused inflation.

Ghana's economy relied heavily on cocoa. Cocoa prices were unstable, but exports usually provided about half of the country's foreign money. Starting in the 1960s, several factors severely limited this income. These included foreign competition, poor government pricing for farmers, and cocoa smuggling. As a result, Ghana's cocoa income continued to fall.

Busia's austerity measures, though wise long-term, angered influential farmers who had supported the PP. These measures were part of Busia's efforts to stabilize the economy, recommended by the International Monetary Fund. They also affected the middle class and salaried workers, who faced wage freezes, tax increases, and rising import prices. This led to protests from the Trade Union Congress. In response, the government sent the army to occupy union headquarters and stop strikes.

The army officers, on whom Busia relied, were also affected by austerity. Knowing this, the Busia government began changing army leadership. This was the final trigger. Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong led a bloodless coup on January 13, 1972, ending the Second Republic.

National Redemption Council Years, 1972–79

The Second Republic was short, but it highlighted the nation's development problems. These included uneven investment and favoritism towards certain groups. Important questions about development priorities remained. After Nkrumah's and Busia's governments failed, Ghana's path to political stability was unclear.

Acheampong's National Redemption Council (NRC) claimed it acted to reverse the previous government's currency devaluation and improve living conditions. To justify their takeover, coup leaders accused Busia of corruption. The NRC aimed to create a military government and didn't plan to return to democracy.

In economic policy, Busia's austerity measures were reversed. The currency was revalued, foreign debt was rejected or rescheduled, and large foreign companies were nationalized. The government also supported prices for basic food imports. They encouraged Ghanaians to be self-reliant in agriculture. These measures were popular at first but didn't solve the country's problems. Industry and transportation suffered as oil prices rose in 1974. Lack of foreign money left the country without fuel. Food production declined as the population grew. People became disillusioned, and corruption accusations surfaced.

The NRC reorganized into the Supreme Military Council (SMC) in 1975. Military officers were put in charge of all ministries. Many Ghanaians hoped this would make the government more efficient.

Soon after, the government tried to stop opposition by banning rumors and independent newspapers. Soldiers broke up student protests, and universities, which were centers of opposition, were repeatedly closed. General Acheampong seemed to favor women over his economic policies. He reportedly signed government checks to acquaintances and gave imported cars to women. Import licenses were given to friends without proper checks.

By 1977, the SMC faced growing non-violent opposition. Discussions about the nation's political future began. Opposition groups (students, lawyers) called for a return to civilian rule. Acheampong and the SMC favored a "union government"—a mix of elected civilians and appointed military leaders—without political parties. Students and intellectuals criticized this idea. Supporters argued it would solve political problems by ending party conflicts and focusing on the economy.

A national vote was held in March 1978 on the union government idea. A narrow margin voted in favor. Opponents protested, saying the vote wasn't fair. The Acheampong government responded by banning organizations and jailing opponents.

The plan for change called for a new constitution, a constituent assembly by November 1978, and elections in June 1979. The ad hoc committee recommended a non-party election and an elected president. The military council would step down, but members could run for office.

In July 1978, other SMC officers forced Acheampong to resign, replacing him with Lieutenant General Frederick W. K. Akuffo. The SMC acted due to pressure to solve the economic crisis. Inflation was estimated at 300% that year. Basic goods were scarce, and cocoa production fell. Akuffo promised to hand over power to a new elected government by July 1, 1979.

Despite Akuffo's promises, opposition continued. Calls for political parties grew. To gain support, the Akuffo government announced that political parties would be allowed after January 1979. Akuffo also gave amnesty to former members of Nkrumah's CPP and Busia's PP. The ban on party politics ended on January 1, 1979. The constitutional assembly finished its draft in May. Everything seemed ready for a new constitutional government in July. However, a group of young army officers overthrew the SMC government in June 1979.

The Rawlings Era Begins

|

Third Republic of Ghana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–1981 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Accra | ||||||||

| Government | Presidential republic (1979-1981) |

||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1979-1981

|

Hilla Limann | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

4 June 1979 | ||||||||

|

• 1979 Ghanaian general election

|

18 June 1979 | ||||||||

|

•

|

31 December 1981 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

31 December 1981 | ||||||||

|

• End of Rawlings government

|

7 January 2001 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

On May 15, 1979, just weeks before elections, a group of junior officers led by Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings tried a coup. It failed, and they were jailed. But on June 4, sympathetic officers overthrew the Akuffo government and freed Rawlings.

Rawlings and the young officers formed the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC). They removed senior officers accused of corruption. The AFRC was caught between soldiers who wanted to punish old regimes and political parties who wanted peaceful change.

Despite the coup and the punishment of former military leaders, elections took place. Ghana returned to constitutional rule by September 1979. Before giving power to the elected government, the AFRC sent a clear message: public officials must be honest and put the community first. The AFRC believed past military leaders had not been accountable.

The administration of Hilla Limann, which began the Third Republic on September 24, 1979, was expected to meet this new standard. Limann's People's National Party (PNP) had only 71 of 140 legislative seats. The opposition Popular Front Party (PFP) won 42 seats. Limann was a former diplomat, not a charismatic leader. Many wondered if his government could handle the country's problems.

The biggest threat to Limann was the AFRC, especially the "June 4th Movement" that watched the civilian government. To stop this, the government ordered Rawlings and other officers to retire. But Rawlings remained a threat as the economy continued to decline. Limann's first budget (1981) estimated inflation at 70%, with a budget deficit of 30% of the GNP. The Trade Union Congress said workers couldn't afford food. Many strikes occurred, lowering productivity. In September, the government announced that striking public workers would be fired. These factors quickly eroded Limann's support. His government fell on December 31, 1981, in another coup led by Rawlings.

Rawlings and his colleagues suspended the 1979 constitution. They dismissed the president and cabinet, dissolved parliament, and banned political parties. They created the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), with Rawlings as chairman, to hold executive and legislative power. The existing legal system remained, but the PNDC added new bodies to fight corruption and tax evasion. They also created Public Tribunals to try crimes. The PNDC said people would exercise power through defense committees in communities and workplaces. Ghana remained a unified government.

In December 1982, the PNDC planned to decentralize government from Accra to regions and districts. But they kept control by appointing regional and district secretaries. Local councils were expected to take over salary payments. In 1984, the PNDC created a National Appeals Tribunal and changed defense committees to Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs).

In 1984, the PNDC also created a National Commission on Democracy to study how to establish participatory democracy. The commission released a "Blue Book" in July 1987, outlining plans for district-level elections. These were held in late 1988 and early 1989 for new district assemblies. One-third of assembly members were appointed by the government.

Rawlings' Return: Early Years (1982–87)

The new government that took power on December 31, 1981, was the eighth since Nkrumah's fall. Called the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), it included Rawlings as chairman. The PNDC said it was different from other military governments. It appointed fifteen civilians to cabinet positions.

On January 5, 1982, Rawlings explained why the Third Republic had to end. He promised to give people, including farmers, workers, and soldiers, a chance to be part of decision-making. He called the takeover a "holy war" to restore dignity to Ghanaians. The PNDC warned that any interference would be "fiercely resisted."

Opposition to the PNDC came from former PNP and PFP members. They argued the Third Republic hadn't had enough time. The Ghana Bar Association (GBA) criticized the use of people's tribunals. Trade Union Congress members were angry when the PNDC ordered them to withdraw wage demands. The National Union of Ghanaian Students (NUGS) even called for the government to hand over power for new elections.

By late June 1982, an attempted coup was discovered, and those involved were punished. Many who disagreed with the PNDC went into exile. They accused the government of human rights abuses.

The PNDC faced different political ideas. Revolutionary leaders agreed on radical change but differed on how to achieve it. Some, like John Ndebugre, wanted a Marxist–Leninist path. Others, like Kojo Tsikata, focused on improving the country's conditions.

To involve the public, the PNDC formed Workers' Defence Committees (WDCs) and People's Defence Committees (PDCs). These committees were meant to involve people in community projects and expose corruption. Public tribunals, outside the normal legal system, tried those accused of anti-government acts.

Opposition groups criticized the WDCs and PDCs, saying they interfered with economic recovery. In response, the PNDC dissolved them on December 1, 1984, replacing them with Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs). Public tribunals, however, remained.

The PNDC also debated how to fund economic recovery. Ghana's economy had suffered greatly from past spending and decline. By December 1981, inflation was over 200%. GDP had fallen. Cocoa, diamonds, timber, and gold production had all dropped.

The PNDC blamed Ghana's poor economy partly on bad political leadership. In 1979, the AFRC had accused former military leaders of corruption and punished them. The overthrow of Limann in 1981 aimed to prevent another weak government from worsening the economy. The solution was to stabilize politics and improve the economy.

At the end of its first year, the PNDC announced a four-year Economic Recovery Programme (ERP). Its goal was economic stability. The government wanted to reduce inflation and build confidence. By 1987, progress was clear. Inflation dropped to 20%. Ghana's economy grew by 6% per year between 1983 and 1987. Donor countries provided an average of $430 million in aid. The PNDC also paid over $500 million in old loan debts. International agencies pledged over $575 million for future programs. With these successes, the PNDC started Phase Two of the ERP, which included selling state-owned businesses and devaluing the currency.

Despite ERP successes, problems remained. High unemployment was a result of the PNDC's strict policies. Critics worried this could derail the recovery.

Unemployment was one political problem. Another was the PNDC's political support base. The PNDC initially appealed to many groups. Still, it faced criticism from students, the GBA, and exiled opposition groups. These groups questioned the military government's legitimacy and its promise to return to constitutional rule. The PNDC needed to show it was moving towards civilian rule.

District Assemblies' Role

The National Commission for Democracy (NCD) existed since 1982. In September 1984, Justice Daniel F. Annan became its chairman. The NCD's launch in January 1985 showed the PNDC's commitment to a new political direction. Annan said past political party systems had ignored development. A new, functional democracy was needed. Old constitutional rules were not acceptable to the new revolutionary spirit.

After two years, the NCD recommended district assemblies. These local governing bodies would allow ordinary people to get involved in politics. The PNDC scheduled elections for these assemblies in late 1988.

The PNDC wanted to establish new values for political behavior. They banned candidates linked to corruption. Candidates could not campaign on their own platforms. They had to run based on personal qualifications and community service.

Once in session, an assembly would be the highest political authority in its district. Members would plan and implement economic development programs. However, district assemblies would follow central government guidance. One-third of assembly members would be traditional chiefs or their representatives, approved by the PNDC. This ensured district plans aligned with national economic recovery.

District assemblies were widely discussed. Some praised them as giving people control over their affairs. Others, especially from the political right, accused the government of trying to stay in power. They argued that if the government truly wanted democracy, it should prioritize national elections. Some questioned the role of traditional chiefs. Others criticized the election rules as undemocratic.

Rawlings responded by explaining the PNDC's strategy. He said district-level elections were a first step towards formal political participation. He emphasized building strong political institutions from the ground up. He dismissed criticisms as "simplistic." For the PNDC, district elections were the start of a political process leading to national-level change.

Despite Rawlings' explanation, opposition groups continued to call the district assemblies a trick to legitimize the military government. Long-time observers saw two main issues: achieving political stability and sustained economic growth. Both had been problems since Nkrumah's time. The ERP and district assemblies were key parts of the PNDC's strategy to address these issues.

End of One-Party Rule

Under pressure to return to democracy, the PNDC allowed a 258-member Consultative Assembly. This assembly, representing districts and organizations, drafted a new constitution. The PNDC accepted it without changes. It was put to a national vote on April 28, 1992, and approved by 92%.

On May 18, 1992, the ban on political parties was lifted for multi-party elections. The PNDC and its supporters formed the National Democratic Congress (NDC). Presidential elections were held on November 3, and parliamentary elections on December 29. Opposition parties boycotted the parliamentary elections. This resulted in a 200-seat Parliament with only 17 opposition members.

Fourth Republic (1993–Present)

The Constitution began on January 7, 1993, starting the Fourth Republic. Rawlings became president, and Parliament members took their oaths. In 1996, the opposition fully participated in the presidential and parliamentary elections. These were described as peaceful and fair. Rawlings was re-elected with 57% of the vote. His NDC party won 133 of 200 Parliament seats, just one short of the two-thirds needed to change the Constitution.

In the 2000 presidential election, Jerry Rawlings supported his vice-president, John Atta-Mills. John Kufuor of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) won and became president on January 7, 2001. The election was seen as free and fair. Kufuor won another term in 2004.

Kufuor's presidency saw social reforms, like the National Health Insurance system in 2003. In 2005, the Ghana School Feeding Programme started, providing free hot meals in poor schools. Ghana's progress was noted internationally.

President Kufuor left power in 2008. The NPP chose Nana Akufo-Addo, Edward Akufo-Addo's son. The NDC's John Atta Mills ran for the third time. After a run-off, John Atta Mills won.

On July 24, 2012, President John Atta Mills died. His vice-president, John Dramani Mahama, took over. He chose Kwesi Amissah-Arthur as his vice. The NDC won the 2012 election, making John Mahama president for his first full term.

John Atta Mills was sworn in as president on January 7, 2009, after a peaceful transition. Mills died of natural causes and was succeeded by vice-president John Dramani Mahama on July 24, 2012.

After the Ghanaian presidential election, 2012, John Dramani Mahama became President-elect and was inaugurated on January 7, 2013. Ghana remained a stable democracy.

As a result of the Ghanaian presidential election, 2016, Nana Akufo-Addo became President-elect. He was inaugurated as the fifth President of the Fourth Republic and eighth President of Ghana on January 7, 2017. In December 2020, President Nana Akufo-Addo was re-elected after a close election.

Religious History of Ghana

Portuguese Catholic missionaries arrived in the 15th century. Protestant missionaries, like the Basel/Presbyterian and Wesleyan/Methodist groups, started Protestantism in Ghana in the 19th century. They began converting people in coastal areas and used schools to train an educated African class. Many secondary schools today are still linked to churches. Since 1960, church schools have been open to everyone, with the state paying for formal education.

Various Christian denominations are in Ghana, including Evangelical Presbyterian and Catholicism. The main organization for most Christians is the Christian Council of Ghana, founded in 1929. It connects different churches with the World Council of Churches. The Seventh-day Adventist Church also has a strong presence.

Islam in Ghana also dates back to a similar period. The Larabanga Mosque, one of West Africa's oldest, was founded in 1421. Islam came to modern Ghana around the 15th century, mainly through trade. Berber traders and religious leaders brought the religion. Islam was introduced in Dagbon by Yaa Naa Zangina, who traded with Muslim kingdoms. Most Muslims in Ghana are Sunni.

Traditional religions in Ghana are still influential because they are closely tied to family and local customs. Traditional beliefs include a supreme being, often called Nyogmo, Mawu, or Nyame. This supreme being is usually seen as distant from daily life and is not directly worshipped.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Ghana para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Ghana para niños

- Economic history of Ghana

- Heads of government of Ghana

- List of Ghana governments

- List of heads of state of Ghana

- Politics of Ghana

- Political history of Ghana

- Accra history and timeline

- Trade and pilgrimage routes of Ghana

- Archaeology of Banda District (Ghana)

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |