History of coal miners facts for kids

For hundreds of years, people have worked as coal miners. These workers became super important during the Industrial Revolution. That's when coal was burned a lot to power machines, trains, and to heat buildings. Because coal was such a key fuel, coal miners have played a big role in workers' rights and political movements ever since.

Since the late 1800s, coal miners in many countries often had big disagreements with their bosses and even the government. Miners' political ideas could be quite strong, sometimes leaning towards far-left views. Many far-left movements got support from miners and their unions, especially in Great Britain. But in France, coal miners were often more traditional in their views. In India, people celebrate Coal Miners Day on May 4th.

Contents

Miners and Big Changes

From the mid-1800s, coal miners often formed strong groups with other workers to fight for better conditions. They were among the first industrial workers to organize themselves to protect their jobs and their communities. Starting in the 1800s and continuing through the 1900s, coal miners' unions became very powerful in many countries. Miners often led left-wing or socialist movements, like in Britain, Poland, Japan, Canada, Chile, and the U.S. in the 1930s.

Historians say that "From the 1880s through the end of the twentieth century, coal miners across the world became one of the most active groups of workers in the industrial world." For example, from 1889 to 1921, British miners went on strike two to three times more often than any other worker group. Some coal areas, like those in Scotland, were known for frequent strikes and strong protests.

In Germany, coal miners showed their strength with big strikes in 1889, 1905, and 1912. However, politically, German miners were not as extreme. One reason was that they had different unions—Socialist, traditional, and Polish—which rarely worked together.

In British Columbia, Canada, coal miners were known for being "independent, tough, and proud." They became "among the most active and strong workers in a very divided province." They were a key part of the socialist movement, and their strikes were frequent, long, and difficult.

In Chile during the 1930s and 1940s, miners supported the Communist Party. This helped elect presidents in 1938, 1942, and 1946. But these political gains didn't last. A big strike in 1947 was stopped by the military, ordered by the very president the miners had helped elect.

After 1945, in Eastern Europe, coal miners were the most politically active group. They strongly supported the Communist governments and received a lot of help from them. However, in the 1980s, Polish miners also played a key role in the anti-Communist Solidarity movement.

Coal Mining in Great Britain

Early Days of British Coal Mining

Some deep mining started in England and Scotland as early as the late 1500s. But deep shaft mining really grew in Britain in the late 1700s, expanding quickly through the 1800s and early 1900s. The location of coalfields helped areas like Lancashire, Yorkshire, and South Wales become wealthy. The pits in Yorkshire that supplied Sheffield were only about 300 feet deep. Northumberland and Durham were the top coal producers and had the first deep mines. In many parts of Britain, coal was dug from drift mines or collected from the surface. Small groups of part-time miners used simple tools.

After 1790, coal production shot up, reaching 16 million tons by 1815. By 1830, it was over 30 million tons. Miners began forming unions to fight for their rights against coal owners. In South Wales, miners were very united. They lived in isolated villages where most people were miners. They had a similar way of life, which, combined with their strong religious beliefs, led to a feeling of equality. They built a "community of solidarity" under the Miners Federation. This union first supported the Liberal Party, then the Labour Party after 1918.

Coal in the 20th Century

Coal became a very political topic, partly because of the tough conditions miners worked in. Their strong presence in remote villages made them very united politically. Much of Britain's "old Left" politics started in coal-mining areas. The main union was the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), started in 1888. The MFGB had 600,000 members in 1908. (It later became the more organized National Union of Mineworkers).

The national coal strike of 1912 was the first national strike by coal miners in Britain. Their main goal was to get a minimum wage. After a million men walked out for 37 days, the UK Government stepped in. They ended the strike by passing a law for a minimum wage. This strike also caused problems for ships because of fuel shortages. Many trips across the Atlantic were canceled, and some passengers were even moved to the Titanic.

Challenges for Miners (1920-1945)

Britain's total coal output had been dropping since 1914.

- Coal prices fell because Germany started exporting "free coal" to France and Italy in 1925. This was part of their payments after World War I.

- When Britain brought back the gold standard in 1925, the British pound became too strong. This made it hard to export goods from Britain. It also raised interest rates, hurting all businesses.

- Mine owners wanted to keep their profits steady, even when the economy was bad. This often meant cutting miners' wages. With the chance of longer working hours too, the industry faced big problems.

- Miners' pay had dropped a lot, from £6.00 to £3.90, in just seven years.

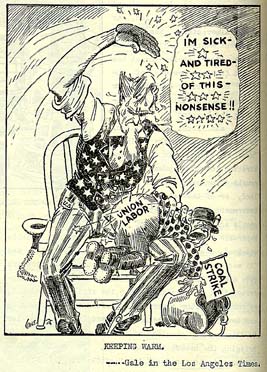

Mine owners announced they would cut miners' wages. The MFGB refused these terms, saying: "Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day." The TUC (a group of unions) promised to support the miners. The Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin decided to help. They said they would pay a subsidy for nine months to keep miners' wages up. A special group, led by Sir Herbert Samuel, would study the mining industry's problems.

This decision was called "Red Friday" because it seemed like a win for workers. But it also gave mine owners and the government time to get ready for a big worker dispute. Herbert Smith, a miners' leader, said: "We have no need to glorify about victory. It is only an armistice."

The Samuel Commission released its report on March 10, 1926. It suggested that the mining industry needed big changes and improvements. It also recommended cutting miners' wages by 13.5% and stopping the government subsidy. Two weeks later, the prime minister said the government would accept the report if others did too.

After the Samuel Commission's report, mine owners said that miners had to accept new rules by May 1st or be locked out. These new rules included longer workdays and wage cuts of 10% to 25%. The MFGB refused the wage cuts and local talks.

The 1926 United Kingdom general strike lasted nine days, from May 4 to May 13, 1926. The TUC called it to try and make the government stop wage cuts and bad conditions for 800,000 locked-out coal miners. About 1.7 million workers went on strike, especially in transport and heavy industries. The government was ready and used middle-class volunteers to keep important services running. There was little violence, and the TUC gave up. The miners gained nothing.

The miners kept fighting for a few more months. But their own financial needs forced them to go back to the mines. By the end of November, most miners were back at work. However, many stayed unemployed for years. Those who found work had to accept longer hours, lower wages, and local wage agreements. The strikers felt like they had achieved nothing. The strike had a huge impact on British coal mining. By the late 1930s, the number of mining jobs had fallen by over a third. But productivity went up, from under 200 tons per miner to over 300 tons by 1939.

British Coal After 1945

In 1947, the British government bought all the coal mines and put them under the National Coal Board (NCB). The industry slowly shrank, even with protests like the UK miners' strike (1984–1985). The 1980s and 1990s saw big changes, with mines being sold to private companies. Many pits were seen as too expensive to run compared to cheap North Sea oil and gas, and compared to how much other European governments helped their coal industries.

The NCB employed over 700,000 people in 1950 and 634,000 in 1960. But different governments kept making the industry smaller by closing mines that were hard to reach or didn't produce much coal. Closures first happened in Scotland, then in North East England, Lancashire, and South Wales in the 1970s. Closures in all coalfields began in the 1980s. This was because demand for British coal dropped. Other European governments gave big subsidies to their coal industries. Also, cheaper coal from places like Australia, Colombia, Poland, and the United States became available.

The NCB faced three major national strikes. The 1972 and 1974 strikes were both about pay, and the National Union of Mineworkers won both times. The miners' strike of 1984–1985 ended with a victory for the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher. This strike is still a sore point in some parts of Britain that suffered from the mine closures afterward. The musical Billy Elliot the Musical, based on the 2000 film, shows this.

British Coal (the new name for the National Coal Board) was sold to private companies in the mid-1990s. Because coal seams were running out and prices were high, the mining industry almost completely disappeared.

In 2008, the last deep coal mine in the South Wales Valleys closed, costing 120 jobs. The coal was simply gone. In 2013, British coal mines employed only 4,000 workers at 30 locations, digging up 13 million tons of coal.

Coal Mining in Western Europe

Belgium's Coal Story

Belgium was a leader in the Industrial Revolution in Europe. It started large-scale coal mining by the 1820s, using methods from Britain. Industrialization happened in Wallonia (French-speaking southern Belgium), starting in the mid-1820s. The availability of cheap coal was a main reason why business owners came there. Many factories, including those for making iron, were built in the coal mining areas around Liège and Charleroi. A key business leader was John Cockerill, an Englishman. His factories in Seraing handled all parts of production by 1825. By 1830, when iron became important, Belgium's coal industry was already well-established. It used steam engines for pumping water out of mines. Coal was sold to local factories and railways, as well as to France and Prussia.

Germany's Coal History

The first important German mines appeared in the 1750s. They were in the valleys of the Ruhr, Inde, and Wurm rivers, where coal was close to the surface. After 1815, business owners in Belgium started the Industrial Revolution in Europe by opening mines and iron factories. In Germany (Prussia), the Ruhr Area coalfields opened in the 1830s. Railroads were built around 1850, and many small industrial towns grew up, focusing on ironworks using local coal. In 1850, an average mine produced about 8,500 tons and employed about 64 people. By 1900, the average mine produced 280,000 tons and employed about 1,400 people.

German miners were divided by their background (Germans and Poles), by religion (Protestants and Catholics), and by politics (Socialist, traditional, and Communist). People often moved in and out of mining camps to nearby industrial areas. Miners split into several unions, each linked to a political party. As a result, the socialist union competed with Catholic and Communist unions until 1933, when the Nazis took control of all of them. After 1945, the socialists became more important.

Coal in the Netherlands

Until the mid-1800s, coal mining in the Netherlands was only around Kerkrade. Using steam engines allowed mining of deeper coal seams to the west. Before 1800, miners worked in small groups that dug out one seam. In the 1900s, mining companies grew much larger. The Roman Catholic church, through Henricus Andreas Poels, actively helped create a Catholic miners' union. This was to stop the growing influence of socialism. Starting in 1965, coal mines were closed down. This was started by socialist minister Joop den Uyl and supported by Catholic union leader Frans Dohmen. In 1974, the last coal mine closed, leading to many job losses in the region.

French Miners and Unions

French miners were slow to form unions. When they did, they tried to avoid strikes if possible. They trusted the national government to improve their lives through special laws, and they were careful to be moderate. Miners' groups had internal problems, but they all disliked using strikes. There were strikes in the 1830s, but these were not organized by unions. Instead, they were spontaneous protests against the owners. One historian said, "The miners were clearly looking backward, wishing for the days of small, non-mechanized mines, run not by distant engineers but by gang leaders chosen by the men themselves." A failed strike in 1869 weakened a new union. Union leaders insisted that the best way was to seek slow improvements by asking for national laws. By 1897, there were many very small, independent mining unions. Together, they only included a small part of the miners. When new mines opened in Nord and Pas-de-Calais, leadership went to their unions, which also followed a moderate approach.

Coal Mining in the United States

Life in 19th Century Coal Camps

Miners in remote coal camps often depended on the company store. This was a store miners had to use because they were often paid only in company scrip (vouchers) or coal scrip. These could only be used at the company store, which often charged higher prices than other stores. Many miners' homes were also owned by the mines. While some company towns were unfair, others were supportive.

Coal was usually mined in remote, often mountainous areas. Miners lived in simple housing provided cheaply by the companies. They shopped at company stores. There were few other things to do besides the railroads and saloons. The anthracite (hard coal) mines of Pennsylvania were owned by large railroads and managed by officials. Scranton was a central city for this. Bituminous (soft coal) mines were owned locally.

The social system in these towns was based more on background than on job. Almost everyone was a blue-collar worker with similar incomes. Welsh and English miners had the highest status and the best jobs, followed by the Irish. Below them were recent immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe. Recent arrivals from the Appalachian hills had even lower status. These groups tended to stick together. Black workers were sometimes brought in to break strikes.

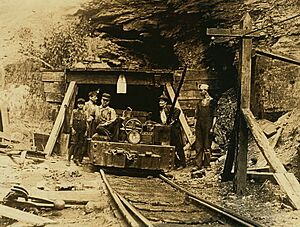

There was little machinery before about 1910. Miners relied on their strength, pickaxes, hand drills, and dynamite to break coal from the walls. They shoveled it into carts pulled by mules, which took it to the weighing station and then to railroad cars. The culture valued physical bravery. Boxing was a popular sport. Opportunities for women were limited until textile companies started opening small factories in larger coal towns after 1900 to employ women. Religion was important, as each group was very loyal to its church. Schooling was limited. Boys hoped to get jobs helping around the mines until they were old enough to work underground as "real" miners.

Segundo, Colorado was a company town where the CF&I coal company housed its workers. It had good housing and helped people improve their lives. It sponsored a YMCA Center, an elementary school, and some small businesses, as well as a company store. However, air pollution was a constant health risk, and houses lacked indoor plumbing. As the need for coal declined, the mine laid off workers, and Segundo's population dropped. After a big fire in 1929, CF&I left town, and Segundo became almost a ghost town.

The Company Store

A company store was common in more isolated areas. It was owned by the company and sold a limited range of food, clothes, and daily needs to employees. It was typical in a company town in a remote area where almost everyone worked for one company, like a coal mine. In a company town, the housing was owned by the company, but there might be independent stores nearby. Company stores had little to no competition, so prices were often not competitive. The store usually accepted "scrip" or non-cash vouchers given by the company before weekly paychecks. It also gave credit to employees before payday.

One expert, Fishback, says:

-

The company store is one of the most disliked and misunderstood economic institutions. In songs, stories, and union speeches, the company store was often shown as a villain, trapping people in endless debt. Nicknames, like the "pluck me," suggest exploitation. These ideas carry over into academic writings, which say the company store was a monopoly.

The stores served many purposes. They were often the local post office and a community center where people could gather. Company stores became less common after miners bought cars and could travel to other stores.

Safety and Health in the Mines

Being a miner in the 1800s meant long hours of hard work in dark mines with low ceilings. Accidents happened often. Young boys worked outside the mine to sort coal from rocks. They were not allowed underground until age 18. Breathing coal dust caused black lung, a serious lung disease. Few miners knew how much it would affect their bodies.

Good Times and Strikes (1897–1919)

The United Mine Workers (UMWA) won a big victory in an 1897 strike by soft-coal miners in the Midwest. They got significant wage increases and grew from 10,000 to 115,000 members. The UMWA faced tougher opposition in the small anthracite region. The owners, controlled by large railroads, refused to meet or talk with the union. The union went on strike in September 1900. Even the union was surprised when miners of all different backgrounds walked out to support the union.

In the Coal Strike of 1902, the UMWA focused on the anthracite coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners were on strike asking for higher wages, shorter workdays, and recognition of their union. The strike threatened to cut off winter fuel to all major cities. President Theodore Roosevelt got involved and set up a group to investigate. This group stopped the strike. The strike never started again. Miners got more pay for fewer hours, and owners got a higher price for coal. However, the owners did not recognize the union as a bargaining group. This was the first time the federal government stepped in as a neutral helper in a labor dispute.

Between 1898 and 1908, coal miners' wages, in both soft and hard coal areas, doubled. Business leaders and political leaders worked with the miners' union on good terms. Experts noted that coal operators found it helpful to support the union's policy of steady wage rates. This prevented fierce competition and falling prices. The UMWA also helped control miners from going on sudden, unauthorized strikes.

The UMWA, under its new young leader John L. Lewis, called a strike for November 1, 1919, in all soft coal fields. They had agreed to a wage deal until the end of World War I. Now they wanted to get some of the money their industry made during the war. The federal government used a wartime law that made it a crime to stop the production or transport of necessary goods. Ignoring the court order, 400,000 coal workers walked out. The coal operators tried to make it seem like a radical plot, saying Lenin and Trotsky had ordered and funded the strike. Some newspapers repeated this.

Lewis, facing criminal charges and aware of the negative publicity, called off his strike. But Lewis didn't fully control the UMWA, which had many different groups. Many local unions ignored his call. As the strike continued into its third week, supplies of the nation's main fuel ran low. The public demanded stronger government action. A final agreement came after five weeks. Miners got a 14% raise, much less than they wanted.

The UMWA was weakened by internal disagreements in the 1920s and lost members. Oil began replacing coal as the nation's main energy source, threatening the industry. The number of coal miners nationwide fell from a high of 694,000 in 1919 to 602,000 in 1929. It dropped sharply to 454,000 in 1939 and 170,000 in 1959.

Coal Mining in Canada

Between 1917 and 1926, Cape Breton coal towns changed from company towns to "labor towns." This showed a shift in who had power locally. The main union, the Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia, started in 1917. It won union recognition, wage increases, and the eight-hour day. The union got its voters organized and took control of town councils. They challenged coal companies on using company police and how taxes were set. The biggest change was the town council's success in limiting the power of company police. These police had often acted as special, unpaid town police officers. The town councils also helped miners during the struggles of the 1920s against the British Empire Steel Corporation's wage cuts.

The Amalgamated union became led by Communists in the 1930s. They encouraged strong action, lots of worker democracy, and resistance to company demands for wage cuts. During World War II, after the Soviet Union was invaded by Germany in 1941, the union suddenly became strong supporters of the war effort. They pushed for maximum coal production. However, the regular miners mostly wanted to get back their lost income. They started slowing down work to force the company to pay higher wages. When wages did go up, output fell. This was because more people were absent, and younger men left for better-paying factory jobs. The remaining men resisted any speedup. The union leaders could not control a dissatisfied and active workforce. Miners fought both the company and their own union leaders.

The political unity of coal miners has often been explained by how isolated they were. They were a similar group of workers living in poor economic and cultural conditions. However, studies in Nova Scotia show that machines in the mines gave miners a lot of control over underground work. Also, the teamwork needed for the job helped miners form close friendships. In contrast, in another coalfield, where miners were mostly unskilled, owners could easily replace workers and weaken the unions.

Women played an important, though often quiet, role in supporting the union movement in coal towns in Nova Scotia, Canada. This was during the difficult 1920s and 1930s. They never worked in the mines. But they gave emotional support, especially during strikes when there was no pay. They managed the family money and encouraged other wives who might have wanted their husbands to accept company terms. Women's labor leagues organized social, educational, and fundraising events. Women also bravely faced "scabs" (workers who crossed strike lines), policemen, and soldiers. They had to make food last and be creative in clothing their families.

Mining Disasters

Mining has always been dangerous. This is because of methane gas explosions, roof cave-ins, and the difficulty of rescuing people. The worst single disaster in British coal mining history was at Senghenydd in the South Wales coalfield. On October 14, 1913, an explosion and fire killed 436 men and boys. It followed many other big Mining accidents, like The Oaks explosion of 1866 and the Hartley Colliery Disaster of 1862. Most explosions were caused by firedamp (methane) igniting, followed by coal dust explosions. Deaths were mainly from carbon monoxide poisoning or not being able to breathe.

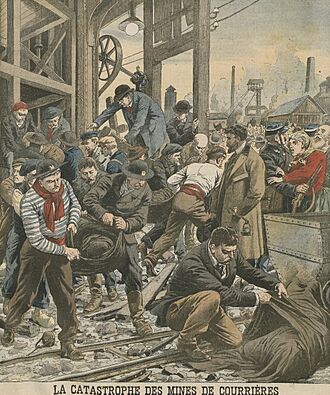

The Courrières mine disaster, Europe's worst mining accident, killed 1,099 miners in Northern France on March 10, 1906. This disaster was only surpassed by the Benxihu Colliery accident in China on April 26, 1942, which killed 1,549 miners.

Besides disasters directly in mines, there have been tragedies caused by mining's impact on the land and communities. The Aberfan disaster, which destroyed a school in South Wales, was directly caused by the collapse of waste piles from the town's coal mine.

Often, songs were written to remember the victims. For example, at least 11 folk songs were made about the 1956 and 1958 disasters at Springhill, Nova Scotia. These events involved 301 miners (113 died, and 188 were rescued).

Images for kids

-

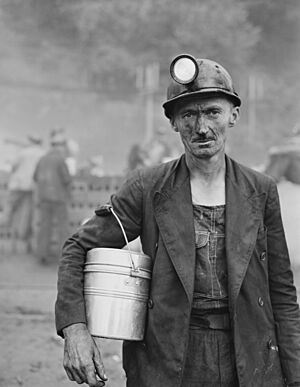

Tribute to coal miners in Pennsylvania.

See also

- History of coal mining

- Coal

- Coal mining

- Coal-mining region

Britain

- Coal mining in the United Kingdom

- 1926 United Kingdom general strike

- South Wales Miners' Federation

- National Union of Mineworkers (Great Britain)

- Midland Counties Miners' Federation

- Northumberland Miners' Association

- Leicestershire Miners' Association

- Thomas Ashton (trade unionist)

Czechoslovakia

- Mine workers council elections in the First Czechoslovak Republic

India

- List of trade unions in the Singareni coal fields

United States and Canada

- Canadian Mineworkers Union

- Cape Breton coal strike of 1981, Canada

- John L. Lewis, American leader 1920–60

- United Mine Workers, U.S. union

- Mary Harris Jones, (Mother Jones), Labor leader

- Coal mining in Plymouth, Pennsylvania

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |