History of the British Virgin Islands facts for kids

The history of the British Virgin Islands is like a story with five main parts. These parts help us understand how the islands changed over time. First, there were the early Native American settlements. Then came the first European settlers. After that, the British took control. Next was the time of emancipation, when slavery ended. Finally, we have the modern era, from 1950 until today. These periods help us see the big changes that shaped the islands.

Contents

Early History of the British Virgin Islands

First People: Arawaks and Caribs

The very first people to live in what we now call the British Virgin Islands were the Arawak Indians. They arrived from South America around 100 BC. Some experts think another group, the Ciboney Indians, might have been there even earlier, around 300 BC. There's also a little bit of proof that people visited these islands for fishing as far back as 1500 BC, but they probably didn't live there all the time.

The Arawaks lived peacefully on the islands until the 1400s. Then, a more aggressive tribe called the Caribs arrived. The Caribs came from other islands in the Lesser Antilles. The Caribbean Sea is actually named after these people! When Europeans later visited the British Virgin Islands, they didn't find any Native Americans living there. However, Christopher Columbus did have a fight with Carib natives on the island of St. Croix.

We are still learning a lot about these early islanders. Many Arawak pottery pieces have been found near Belmont and Smuggler's Cove on Tortola. Other Arawak items have been discovered in places like Soper's Hole, Apple Bay, and Cane Garden Bay. New discoveries often help historians understand more about these first settlers.

European Explorers Arrive

The first European to see the Virgin Islands was Christopher Columbus in 1493. This was during his second trip to the Americas. Columbus named them Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Vírgenes, which means Saint Ursula and her 11,000 Virgins. This name was later shortened to Las Vírgenes (The Virgins). He also named Virgin Gorda (the Fat Virgin), thinking it was the biggest island.

Spain claimed the islands because Columbus discovered them, but they never actually settled there. In 1508, Juan Ponce de León settled in Puerto Rico. Spanish records suggest they used the Virgin Islands for fishing, but nothing more. These records might have been talking about the nearby U.S. Virgin Islands.

Other explorers visited too. Sebastian Cabot and Thomas Spert came in 1517. Sir John Hawkins visited three times, starting in 1542. He brought enslaved people to Hispaniola. On his third trip, he was with a young captain named Francis Drake. Drake returned in 1585 and anchored near Virgin Gorda before attacking Santo Domingo. He came back one last time in 1595 and died on that trip. The main channel in the British Virgin Islands is named in his honor.

In 1598, George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, used the islands as a base. He was preparing to attack Puerto Rico during a conflict between England and Spain.

Later, King James I of England gave a special permission to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, for Tortola and other islands like Anguilla and Anegada. He also got rights to Barbados and St. Kitts in 1627. But neither he nor his son ever tried to settle the northern islands.

Dutch Settlers Build a Home

The first lasting European settlements in the British Virgin Islands were started by a Dutch privateer named Joost van Dyk. He set up a base in Soper's Hole on Tortola. By 1615, Spanish records noted his settlement was growing. He traded with Spanish colonists in Puerto Rico and grew cotton and tobacco.

Some stories say the Spanish were the first to settle here, mining copper on Virgin Gorda. But there's no proof from old sites that the Spanish lived here or mined copper before the 1800s.

By 1625, the Dutch West India Company recognized van Dyk as the "Patron" of Tortola. He moved his operations to Road Town. That same year, van Dyk helped a Dutch admiral who attacked San Juan, Puerto Rico. In return, the Spanish attacked Tortola in September 1625. They destroyed its defenses and settlements. Joost van Dyk escaped to the island now named after him, Jost Van Dyke. He later moved to St. Thomas until the Spanish left.

The Dutch West India Company saw the Virgin Islands as very important. They were halfway between Dutch colonies in South America (now Suriname) and their main settlement in North America, New Amsterdam (now New York City). The Dutch built large stone warehouses at Freebottom, near Port Purcell, to help with trade between North and South America.

Early Dutch Life and Challenges

The Dutch settlers built small forts and a three-cannon fort on a hill above the warehouse. This is where the English later built Fort George. They also built a wooden lookout post above Road Town, which later became Fort Charlotte. Troops were also stationed at the Spanish "dojon" near Pockwood Pond, which is now called Fort Purcell or "the Dungeon."

In 1631, the Dutch West India Company heard rumors of copper on Virgin Gorda. They set up a settlement there, known as "Little Dyk's" (now Little Dix).

Spain attacked Tortola again in 1640, led by Captain Lopez. They attacked once more in 1646 and 1647. Captain Francisco Vincente Duran led these attacks. The Spanish ships blocked Road Harbour and landed men at West End. They attacked Fort Purcell by land, killing the Dutch defenders. Then they attacked Road Town, killing everyone and destroying the settlement. They didn't bother with smaller settlements like those in Baugher's Bay or on Virgin Gorda.

Dutch West India Company Changes Plans

The Dutch settlements weren't making money. It seems the Dutch settlers were more interested in privateering (like legal piracy) than in trading. The whole Dutch West India Company wasn't doing well financially either.

So, the Company changed its plan. It decided to give islands like Tortola and Virgin Gorda to private individuals for settlement. They also wanted to set up places to support the slave trade, as they were bringing enslaved people from Africa. Tortola was sold to Willem Hunthum in the 1650s. After this, the Dutch West India Company's interest in the islands mostly ended. In 1665, a British privateer attacked the Dutch settlers on Tortola. He captured 67 enslaved people and took them to Bermuda. This is the first time we have records of enslaved people being held in the British Virgin Islands.

In 1666, a report said that some Dutch settlers had been forced out by British "brigands and pirates." However, many Dutch people still remained.

1672: British Take Control

England took control of the British Virgin Islands in 1672, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. They have been in charge ever since. The Dutch said that in 1672, Willem Hunthum placed Tortola under the protection of Sir William Stapleton, the English Governor-General of the Leeward Islands. Stapleton reported that he had "captured" the islands soon after the war started.

Colonel William Burt was sent to Tortola and took control by July 13, 1672. Burt didn't have enough men to stay and occupy the islands. Before leaving, he destroyed the Dutch forts and took all their cannons to St. Kitts.

The war ended with the Treaty of Westminster (1674). This treaty said that all lands captured during the war should be returned. The Dutch had the right to get their islands back. But at that time, the Dutch were fighting the French, so they couldn't immediately get their islands back. The British didn't think the islands were very valuable, but they didn't want to give them up for strategic reasons. After long talks, Stapleton was told in June 1677 to keep Tortola and the nearby islands.

In 1678, the war between France and the Dutch ended. The Dutch then focused on Tortola. In 1684, the Dutch ambassador formally asked for Tortola back. He didn't base his claim on the treaty, but on the rights of Willem Hunthum's widow. He said the island wasn't captured but was given to the British for protection. The ambassador even showed a letter from Stapleton promising to return the island.

At this time (1686), Stapleton was on his way back to Britain. The Dutch were told that Stapleton would be asked to explain why his actions didn't match his promise. Unfortunately, Stapleton died in France. The British knew that other Caribbean lands captured from the Dutch had already been returned. So, in August 1686, the Dutch ambassador was told that Tortola would be returned. Instructions were sent to Nathaniel Johnson, the new Governor of the Leeward Islands.

But Tortola was never actually given back to the Dutch. One problem was that Johnson's orders were to return the island to someone with "sufficient authority." However, most of the Dutch colonists had left, losing hope of getting it back. There was no official Dutch government representative to receive the island. So, Johnson did nothing.

In November 1696, another claim was made for the island. A merchant from Rotterdam claimed to have bought Tortola in 1695. This merchant was from Brandenburg, and the British didn't like the idea of Tortola being controlled by Brandenburg. The British rejected this claim, saying Stapleton had conquered Tortola, not been entrusted with it. The British also wrongly claimed to have discovered Tortola first. During these talks, the British also remembered older claims, like the 1628 permission given to the Earl of Carlisle. In February 1698, the British decided to keep the islands, and no more claims were accepted.

What Islands Were Part of the Territory?

Even though the British have controlled the British Virgin Islands since 1672, some other islands were also under British control at different times but are no longer part of the territory. When the British took control, these islands were considered part of the Virgin Islands.

- St. Thomas. The British first claimed St. Thomas (and St. John). But in 1717, the Danish challenged their claim. Unlike the long argument over Tortola, the St. Thomas dispute was quickly settled. The Danish claim was strong. They had a treaty with Britain from 1670 that allowed the Danish West India Company to take and occupy these islands. On May 25, 1672, the Danes took St. Thomas and found that the British settlers had left weeks earlier. The British couldn't really argue against the Danes keeping the island.

- St. John. Right after the St. Thomas dispute, a new argument started over St. John. The Danes tried to settle it on March 23, 1718. The British Governor, Walter Hamilton, immediately sent a ship to the island. There were tense talks, but the Danes refused to leave St. John, and the British decided not to use force. The British were more worried about St. Croix, thinking the Danes would want that island too.

- St. Croix (or St. Cruz). The British fears were right. In 1729, the Danes claimed St. Croix, saying the French had sold it to them. St. Croix had been settled by different European nations, but in 1645, fighting broke out, and the English governor was killed. The English kicked out the Dutch, and the French moved to Guadeloupe, leaving the British in charge. But in 1650, the Spanish invaded from Puerto Rico, and the British gave up the island. Later that year, the Dutch tried to return but were killed or captured by the Spanish. The French Governor of the Caribbean then attacked the island and drove out the Spanish. He couldn't set up a colony, so he gave the island to the Knights Hospitaller in 1653. In 1665, St. Croix was bought by the French West India Company. When that company failed in 1674, the King of France claimed it. But the island was later ordered to be abandoned because it wasn't making money. The date it was abandoned became a big argument. In May 1733, the French claimed to sell the island to the Danish West India Company. If the French had only left it in 1695 (as they said), it was French when the treaty was made. If they left in 1671 (as the British claimed), then St. Croix should have been British. In the end, the French had documents to support their claim, and the British didn't. So, the British stopped fighting the French sale of the island to the Danes.

Britain did conquer St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix in March 1801 during the Napoleonic Wars. But they gave them back in March 1802. They were taken again in December 1807 but returned by the Treaty of Paris (1815). After that, they stayed under Danish control until 1917, when they were sold to the U.S.A. for $25 million. They were then renamed the "U.S. Virgin Islands."

- Vieques (or Crab Island). Vieques was sometimes settled by the British, but Spanish soldiers from Puerto Rico always drove them away. In the early 1700s, British settlers on Vieques were moved to St. Kitts. Interestingly, a century later, after slavery ended, many former enslaved people from the British Virgin Islands went to Vieques to find work, even though Vieques still had slavery.

Relationships with the Danes were difficult. The Danes often took timber from nearby British islands, which was against British rules. British ships that got stuck near St. Thomas were charged huge fees for rescue. Also, St. Thomas became a base for pirates and privateers, and the Danish Governor either couldn't or wouldn't stop them. During the War of the Spanish Succession, the Danes supported the French colonies. They even allowed the French to sell captured British ships in Charlotte Amalie. The British invasions in the early 1800s didn't help relations. Later, smuggling and illegal sales of enslaved people by people from St. Thomas also caused problems for British authorities.

Law and Order in the Early Days

Even after the British fully controlled the islands, not many people moved there. Settlers were afraid of Spanish attacks. There was also a constant worry that the islands might be given back to another country, like what happened with St. Croix. Spanish raids in 1685 and ongoing talks between the Dutch and British made the islands almost empty. From 1685 to 1690, only two people lived there: Mr. Jonathan Turner and his wife. By 1690, the population grew to fourteen, and by 1696, it was fifty.

From 1678, the British appointed a deputy-governor for the territory. This role was a bit unclear and didn't have much power. The deputy-governor was supposed to appoint a local governor, but it was hard to find someone suitable. In 1709, Governor Parke said that the people "live like wild people without law or Government, and have neither Divine nor Lawyer amongst them..."

The Virgin Islands didn't get their own law-making body until 1773.

Early attempts to set up a government in the territory didn't work well. The uncertainty of who owned the islands and the British government's mixed feelings about them affected the early population. For many years, only people fleeing debts, pirates, and those running from the law were willing to risk settling in the Virgin Islands. Visitors often commented on the lack of law and order and the lack of religious practice among the people.

The territory was granted a Legislative Assembly on January 27, 1774. However, it took another ten years for a proper government system to be set up. Part of the problem was that there were so few people on the islands, it was almost impossible to form a government. In 1778, George Suckling arrived to be the Chief Justice. But a court wasn't actually set up until 1783. Even then, powerful local people made sure Suckling couldn't start his job. The islands had a court but no judge. Suckling eventually left in 1788 without ever working or being paid. He was poor and angry because local interests were afraid that if a court was set up, their creditors (people they owed money to) would come after them. Suckling openly shared his views on the state of law and order. He said the people of Tortola were "in a state of lawless ferment. Life, liberty, and property were hourly exposed to the insults and depredations of the riotous and lawless." He called the island "a shocking state of anarchy."

Almost 100 years later, in 1810, Governor Hugh Elliot said similar things. He found the colony in a "state of irritation, nay, I had almost said, of anarchy." A writer named Howard, who was selling enslaved people from a shipwreck in Tortola in 1803, wrote that "Tortola is well nigh the most miserable, worst-inhabited spot in all the British possessions... this unhealthy part of the globe appears overstocked with each description of people except honest ones."

Quaker Settlers

Even though they were few in number and only stayed from 1727 to 1768, the Quaker settlers were important. First, the Quakers strongly opposed slavery. This helped improve how enslaved people were treated in the territory compared to other Caribbean islands. It also led to a large number of free black people living in the islands. Second, many famous historical figures came from this small Quaker community, including John C. Lettsome and William Thornton.

Fortifications

Between 1760 and 1800, the British greatly improved the islands' defenses. They often built on older Dutch forts. New structures with cannons were put up at Fort Charlotte, Fort George, Fort Burt, Fort Recovery, and a new fort in Road Town called the Road Town Fort. At that time, plantation owners were expected to fortify their own lands. So, Fort Purcell and Fort Hodge were built by owners.

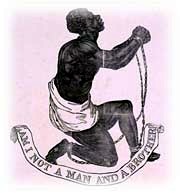

The Slave Economy

Slavery is a very important part of the history of the British Virgin Islands, just like in most Caribbean countries. As plantation owners settled Tortola and Virgin Gorda, enslaved labor became necessary for the economy. The number of enslaved people grew very quickly in the 1700s. In 1717, there were 547 black people (all assumed to be enslaved). By 1724, there were 1,430, and by 1756, there were 6,121. This increase in enslaved people matched the growth of the British Virgin Islands' economy at the time.

Slave Revolts

Uprisings were common in the territory, just like elsewhere in the Caribbean. The first major uprising in the British Virgin Islands happened in 1790 on Isaac Pickering's estates. It was quickly stopped, and the leaders were executed. The revolt started because of a rumor that enslaved people in England had been freed, but the plantation owners were hiding this news. This same rumor would cause later revolts too.

Other rebellions happened in 1823, 1827, and 1830. Each time, they were quickly put down.

Perhaps the most important slave uprising happened in 1831. A plan was discovered to kill all the white men in the territory and escape to Haiti (which was the only free black republic in the world at the time). They planned to take all the white women by boat. Even though the plan wasn't very well organized, it caused a lot of panic. Military help was brought in from St. Thomas. Several people involved in the plot were executed.

It's not surprising that slave revolts increased sharply after 1822. In 1807, the trade of enslaved people was stopped. Although existing enslaved people were still forced to work, the Royal Navy patrolled the Atlantic, capturing slave ships and freeing their human cargo. Starting in 1808, hundreds of freed Africans were brought to Tortola by the Navy. After serving a 14-year "apprenticeship," they became completely free. Naturally, seeing free Africans in the territory caused huge anger and jealousy among the existing enslaved population, who felt this was very unfair.

1834: Emancipation and Change

Slavery was abolished on August 1, 1834. To this day, it is celebrated with a three-day public holiday in August in the British Virgin Islands. The original emancipation document is kept in the High Court. However, the end of slavery wasn't as sudden as some people think. Emancipation freed 5,792 enslaved people in the territory. But at that time, there were already many free black people, possibly as many as 2,000. Also, the effect of abolition was gradual. The freed enslaved people were not completely free right away. Instead, they entered a forced apprenticeship that lasted four years for house slaves and six years for field slaves. They had to provide 45 hours of unpaid labor a week to their former masters and couldn't leave their homes without permission. This was meant to slowly reduce the reliance on enslaved labor. The local government later shortened this period to four years for everyone to calm growing anger among the field slaves.

Joseph John Gurney, a Quaker, wrote that plantation owners in Tortola were "decidedly saving money by the substitution of free labor on moderate wages, for the deadweight of slavery."

It's hard to measure the exact economic effects of abolition. The original slave owners lost a lot of money. They received £72,940 from the British Government as compensation, but this was only a small part of the true value of the freed enslaved people. In terms of money coming in, while the slave owners lost "free" labor, they no longer had to pay to house, clothe, and provide medical care for their former enslaved people. This sometimes almost balanced out. The former enslaved people usually worked for the same masters but received small wages. From these wages, they had to pay for things their masters used to provide. However, some former enslaved people managed to save money, which shows that slave owners generally had less income and less wealth after abolition.

Decline of the Sugar Industry

Many people believe that the economy of the British Virgin Islands got much worse after slavery was abolished. While this is true, the decline had several different causes. In 1834, the territory's economy relied on farming two main crops: sugarcane and cotton. Sugar was much more profitable.

Soon after slavery ended, the territory was hit by a series of hurricanes. At that time, there was no way to predict hurricanes, and their effects were terrible. A very strong hurricane in 1837 destroyed 17 of the territory's sugar factories. More hurricanes hit in 1842 and 1852. Two more struck in 1867 and 1871. The islands also suffered from a severe drought between 1837 and 1847, which made growing sugar almost impossible.

To make things worse, in 1846, the United Kingdom passed a law to make duties (taxes) on sugar grown in the colonies equal. This made sugar prices fall, which was another big blow to plantations in the British Virgin Islands.

In 1846, a large trading company called Reid, Irving & Co. collapsed. This company owned 10 sugar estates in the British Virgin Islands and employed 1,150 people. But its failure had a much wider impact. The company also acted like a bank, allowing people to get credit. Also, it was the only direct way to communicate with the United Kingdom. After its collapse, mail had to be sent through St. Thomas and Copenhagen.

By 1848, Edward Hay Drummond Hay, the President of the British Virgin Islands, reported that "there are now no properties in the Virgin Islands whose holders are not embarrassed for want of capital or credit sufficient to enable them to carry on the simplest method of cultivation effectively."

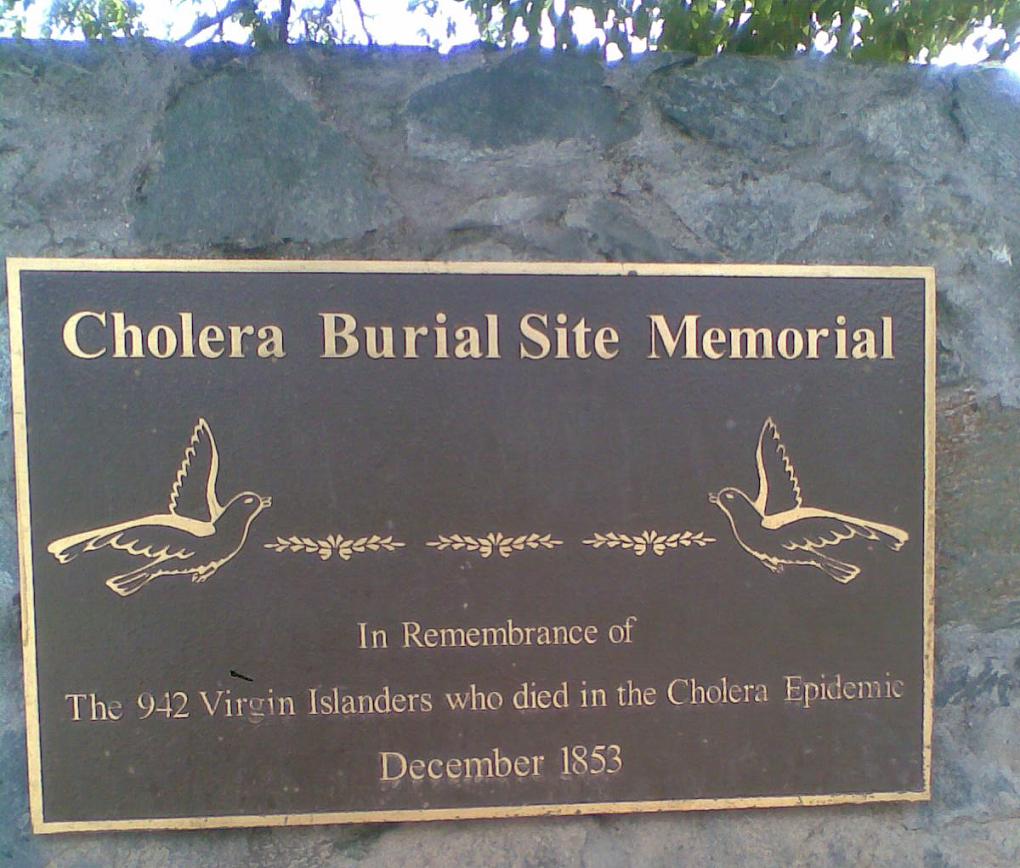

In December 1853, there was a terrible outbreak of cholera in the territory. It killed nearly 15% of the population. This was followed by a smallpox outbreak on Tortola and Jost Van Dyke in 1861, which caused another 33 deaths.

Until 1845, the value of sugar exported from the territory varied but averaged around £10,000 per year. After that, except for 1847 (a very good year), the average for the next 10 years was less than £3,000. By 1852, it had fallen below £1,000 and never recovered.

While this was bad news for the islands as a whole, it meant that the value of land dropped sharply. This allowed the newly freed black community to buy land, which they might not have been able to do otherwise. It also set the stage for the future small-scale farming economy of the British Virgin Islands.

Insurrection and Unrest

Soon after emancipation, the newly freed black population became increasingly unhappy. Freedom had not brought the prosperity they had hoped for. Economic decline led to higher taxes, which made everyone unhappy, both former enslaved people and other residents.

In 1848, a major disturbance happened. One cause was a slave revolt in St. Croix, which increased excitement in the islands. But the free people of Tortola were more concerned about two other issues: the appointment of public officials and the crackdown on smuggling. Although Tortola had sixteen public officials of color, all but one were "foreigners" from outside the territory. During the economic decline, smuggling was one of the few ways to make money. New laws that imposed harsh fines (with hard labor for not paying) were very unpopular. The anger was aimed at the magistrates by small shopkeepers, especially the magistrate Isidore Dyett. However, Dyett was popular with the rural people, who respected him for protecting them from unfair planters. The leaders of the uprising thought their attack would lead to a general revolt, but choosing Dyett as a target made them lose popular support, and the disturbance eventually ended.

However, the uprising of 1853 was much more serious and had more lasting consequences. It was arguably the most important event in the islands' history. Taxes and economic problems were also at the root of this disturbance. In March 1853, two Methodist missionaries asked the Assembly to be freed from taxes. The Assembly said no. One missionary is said to have replied, "we will raise the people against you." Later meetings increased the general unhappiness. Then, in June 1853, the legislature passed a tax on cattle. Unwisely, the tax was to start on August 1, the anniversary of emancipation. This tax would hit the rural community of color the hardest. There was no violent protest when the law was passed. Some suggest that riots could have been avoided if the legislature had been more careful in enforcing it. However, the history shows that an uprising was always possible and just needed a reason to start.

On August 1, 1853, a large group of rural workers came to Road Town to protest the tax. But instead of trying to calm things down, the authorities immediately read the Riot Act and arrested two people. Violence then broke out almost immediately. Several police officers and magistrates were badly beaten. Most of Road Town was burned down, and many plantation houses were destroyed. Cane fields were burned, and sugar mills were ruined. Almost all the white population fled to St. Thomas. President John Chads showed courage but little good judgment. On August 2, 1853, he met with 1,500 to 2,000 protesters. But all he would promise was to tell their complaints to the legislature (which couldn't meet because all the other members had fled). One protester was shot (the only recorded death during the disturbances), which caused the rampage to continue. By August 3, 1853, the only white people left in the territory were John Chads, the Collector of Customs, a Methodist missionary, and the island's doctor.

The riots were eventually stopped with military help from St. Thomas and British troops sent by the Governor of the Leeward Islands from Antigua. Twenty of the riot leaders were sentenced to long prison terms; three were executed.

"Decline and Disorder"

The time after the 1853 riots has been called a period of "decline and disorder" by one historian. Some people have suggested that the white population refused to return, and the islands became overgrown. But this is an exaggeration. While many white people did not return to their ruined estates, some did and rebuilt. However, the rebuilding needed after the uprising, along with the uncertainty it created and the existing poor economic conditions, led to an economic depression that lasted for nearly a century. It took two full years for the schools in the territory to open again.

Tensions continued to simmer, and local unrest remained high. Exports continued to drop, and many people left the islands to find work elsewhere. In 1887, a plan for an armed rebellion was discovered. In 1890, a dispute over smuggling led to more violence. A resident named Christopher Flemming became a local hero just for standing up to authority. In each case, widespread damage was prevented by bringing in extra help for the local authorities from Antigua and, in 1890, from St. Thomas.

While the violence showed unhappiness with economic decline and lack of services, it would be wrong to call this period a "Dark Ages" for the territory. During this time, for the first time, there was a significant increase in the number of schools. By 1875, the territory had 10 schools, which was amazing considering there were no working schools after the 1853 uprising. This period also saw the first British Virgin Islander of color, Fredrick Augustus Pickering, appointed as President in 1884.

Pickering stepped down in 1887. In 1889, the title of the office was changed to Commissioner, showing a clear decrease in administrative duties. Offices were also combined to save money on salaries. The Council itself became less and less effective. It barely avoided being dissolved by appointing two popular local figures, Joseph Romney and Pickering.

Modern Developments

However, in 1901, the Legislative Council was finally officially dissolved. The islands were then run by the Governor of the Leeward Islands, who appointed a commissioner and an executive council. The territory was not doing well economically, and social services had almost disappeared. Many people left, especially for St. Thomas and the Dominican Republic. Britain offered very little help or concern, partly because of the two World Wars fought during this time.

In 1949, an unexpected hero appeared. Theodolph H. Faulkner was a fisherman from Anegada. He came to Tortola with his pregnant wife and had a disagreement with the medical officer. He then went to the marketplace and for several nights spoke passionately against the government. His words resonated with people, and a movement began. Led by community leaders like Isaac Fonseca and Carlton de Castro, on November 24, 1949, over 1,500 British Virgin Islanders marched to the commissioner's office and presented their complaints. Their petition began:

"We want to decide our local affairs ourselves. We have grown past the stage where one official, or a small group of officials, makes decisions for us... We want the right to decide how our money is spent and what our laws and policies will be."

1950 – Self-Government Begins

Because of the protests the year before, the British government brought back the Legislative Council in 1950 under a new constitution. The return of the Legislative Council is often seen as a small part of history, just a step towards the more important government changes in 1967. The 1950 constitution was always meant to be temporary. But after being denied any form of democratic control for nearly 50 years, the new council didn't sit idly by. In 1951, money was brought in from the Colonial Welfare and Development office to help farmers. In 1953, the Hotel Aid Act was passed to help the growing tourism industry. Until 1958, the territory only had 12 miles of roads suitable for cars. Over the next 12 years, the road system greatly improved, connecting West End to the East End of Tortola. Tortola was also connected to Beef Island by a new bridge, the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge. The Beef Island airport (now named after Terrance B. Lettsome) was built soon after.

Outside events also played a role. In 1956, the Leeward Islands Federation was ended. This gave the British Virgin Islands more political importance. The council, proud of its new powers, chose not to join the new Federation of the West Indies in 1958. This decision would later be very important for the development of the offshore finance industry.

In 1967, a new constitution was put into effect. This constitution gave much more power to the local government and introduced true ministerial government to the British Virgin Islands. Elections followed in 1967, and a relatively young Lavity Stoutt was elected as the first Chief Minister of the territory.

Financial Services Boom

The fortunes of the territory greatly improved in the late 1900s with the start of the offshore financial services industry. Michael Riegels, a former president of the BVI's Financial Services Commission, tells a story about how the industry began. An unknown date in the 1970s, a lawyer from New York called him with an idea to create a company in the British Virgin Islands. This company would take advantage of a tax treaty with the United States. Within a few years, hundreds of such companies were created.

The United States government eventually noticed this and ended the treaty in 1981.

In 1984, the British Virgin Islands tried to get back some of the lost offshore business. They passed a new law called the International Business Companies Act. Under this law, an offshore company could be formed that was free from local taxes. This idea was only a small success until 1991. That year, the United States invaded Panama to remove General Manuel Noriega. At the time, Panama was one of the biggest providers of offshore financial services in the world. But after the invasion, that business left, and the British Virgin Islands was one of the main places it went.

In 2000, a report by KPMG found that nearly 41% of the world's offshore companies were formed in the British Virgin Islands. The British Virgin Islands is now one of the world's leading offshore financial centers. It also has one of the highest incomes per person in the Caribbean.

Hurricane Irma: A Recent Challenge

The islands were hit by Hurricane Irma on September 6, 2017. This powerful storm caused huge damage, especially on Tortola, and led to four deaths in the BVI. The Governor, Gus Jaspert, declared a state of emergency, which was the first time this had ever happened under the territory's constitution. The Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency also declared a state of emergency. The most significant damage was on Tortola. The UK's Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson visited Tortola on September 13, 2017. He said the damage reminded him of photos of Hiroshima after the atomic bomb.

By September 8, the UK government sent troops with medical supplies and other aid. More troops were expected to arrive soon. A larger ship, HMS Ocean, carrying more help, was expected to reach the islands in about two weeks.

The damage to roads, buildings, and power lines was extensive. It took nearly six months to restore public electricity to the entire territory. After the hurricane, entrepreneur Richard Branson, who lives on Necker Island (British Virgin Islands), asked the UK government to create a huge disaster recovery plan for the damaged British islands. He said this plan should include "both short-term aid and long-term infrastructure spending." Premier Orlando Smith also asked for a full aid package to rebuild the BVI. On September 10, British Prime Minister Theresa May promised £32 million to the Caribbean region for hurricane relief.

Fourteen days after Hurricane Irma, the territory was hit again by Hurricane Maria. This was also a Category 5 storm, though not as strong as Irma. However, the eye of the storm passed south of St. Croix, so the damage was minimal compared to Hurricane Irma.

In May 2018, the Immigration Department announced that the population of the territory had dropped by about 11% since Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck the previous year.

See also

- British Virgin Islands

- History of the Caribbean

- History of the United States Virgin Islands

- List of presidents of the British Virgin Islands (1741–1887)

- List of administrators of the British Virgin Islands (1887–1971)

- List of governors of the British Virgin Islands (1971–present)

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |