History of the salt tax in British India facts for kids

Salt has been taxed in India for a very long time. However, this tax became much higher when the British East India Company started to rule parts of India. In 1835, special taxes were put on Indian salt to make it easier to import salt from other places. This made a lot of money for the traders of the British East India Company. When the British government took over India from the Company in 1858, the taxes stayed.

The strict salt taxes made by the British were strongly disliked by the Indian people. In 1885, at the first meeting of the Indian National Congress in Bombay, a key leader named S. A. Saminatha Iyer spoke out against the salt tax. More protests happened in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These protests led to Mahatma Gandhi's famous Salt Satyagraha (a peaceful protest) in 1930. Other similar protests followed in different parts of the country.

After Gandhi was arrested, Sarojini Naidu led the peaceful protesters, called satyagrahis, to the Dharasana Salt Works in Gujarat. She was also arrested by the police. C. Rajagopalachari broke the Salt Laws in Vedaranyam, in Madras Province, that same year. Thousands of people were arrested and put in jail. The British government eventually gave in and invited Mahatma Gandhi to England for a meeting. Gandhi's Dandi March was widely reported in the news and became a very important moment in India's fight for freedom.

However, the salt tax stayed in place. It was finally removed only when Jawaharlal Nehru became the prime minister of the temporary government in 1946. After India became independent, a salt tax was brought back in 1953. This tax was later removed and replaced by the Goods and Services Tax in 2017, which does not tax salt.

Contents

Salt Taxes Around the World

Salt has been taxed in many parts of the world throughout history.

Ancient Salt Taxes

One of the earliest mentions of salt taxation is in a Chinese book called Guanzi, written around 300 BCE. This book suggested different ways to tax salt. The ideas from Guanzi became the official salt policy for early Chinese Emperors. At one point, salt taxes made up more than half of China's income and even helped pay for building the Great Wall of China.

Salt was also important in the ancient Roman Empire. The first major Roman road, the Via Salaria, or Salt Road, was built to transport salt. But unlike the Chinese, the Romans did not control all the salt trade themselves.

Salt Taxes in Britain

In Britain, there are mentions of salt taxes in the Domesday Book, a very old record. These taxes had mostly disappeared before the time of the Tudor kings and queens. They were brought back in 1641 during the Commonwealth period. But people protested so much that the taxes were removed when the monarchy returned in 1660. They were put back again in 1693 under William III. The tax was set at two shillings for foreign salt and one shilling for local salt, with no tax on salt used for fishing. In 1696, the tax was doubled and stayed until it was removed in 1825. About 600 full-time officials worked to collect these taxes.

Salt Taxes in India

Where Salt Was Produced in India

Salt has been made along the Rann of Kutch on the west coast of India for about 5,000 years. The Rann of Kutch is a large marshy area that gets cut off from the rest of India during monsoon season when the sea floods the low lands. But when the seawater dries up in summer, it leaves behind a layer of salt. This salt is collected by workers called malangas.

On the east coast, a lot of salt could be found along the coast of Odisha. The salt made in Odisha, in areas called khalaris, was considered the best quality in all of India. There was always a demand for Odisha salt in Bengal. When the British took over Bengal, they also needed this salt and traded for it. Slowly, they took control of all Odisha salt trade in Bengal. To stop people from smuggling salt, they sent armies into Odisha, which led to them conquering Odisha in 1803.

Salt Taxes Before British Rule

Salt was taxed in India even before the British arrived, as far back as the Mauryan times. Taxes on salt were common during the time of Chandragupta Maurya. An ancient book called Arthashastra mentions a special officer, the lavananadhyaksa, who was in charge of collecting the salt tax. Taxes were also placed on imported salt, which was about 25 percent of its total value.

In Bengal, there was a salt tax during the Mughal Empire. It was 5% for Hindus and 2.5% for Muslims.

British East India Company and Salt Taxes

In 1759, two years after winning the Battle of Plassey, the British East India Company gained control of land near Calcutta where salt was made. To make more money, they doubled the land rent and added charges for transporting salt.

In 1764, after winning the Battle of Buxar, the British started to control all the income from Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. Robert Clive, who became governor again in 1765, made the sale of tobacco, betel nut, and salt a monopoly for the senior officers of the British East India Company. This meant only they could sell these items. They gave contracts to deliver salt to storage places, and merchants had to buy from these places.

The leaders in England were very angry about this and said:

We think it is too shameful and beneath our dignity to allow such a monopoly.

Clive offered the company 1,200,000 rupees each year from the profits. However, the leaders in England were firm. Because of their pressure, the monopoly on tobacco and betel nut was stopped on September 1, 1767. The salt monopoly was ended on October 7, 1768.

In 1772, the governor-general, Warren Hastings, brought the salt trade back under the company's control. Salt works were rented out to farmers who agreed to sell salt to the company at a set price. But there was a lot of corruption, and the money from salt trade dropped to 80,000 rupees by 1780. This, along with the unfair treatment of the malangas (salt workers) by their landlords, made Hastings create a new system for controlling the salt trade in India.

In 1780, Hastings put the salt trade back under government control. He divided the system into different areas, each managed by an agent and overseen by a controller. This system continued, with small changes, until India became independent in 1947. Under this new system, the malangas sold salt to the agents at a certain price, which was first 2 rupees per maund (about 82 pounds). A tax of 1.1 to 1.5 rupees per maund was added. This new system worked well. In 1781–82, the salt income was 2,960,130 rupees. The company received 6,257,750 rupees from salt in 1784–85.

From 1788 onwards, the company started selling salt to wholesalers through auctions. As a result, the British East India Company increased the tax to 3.25 rupees per maund. The wholesale price of salt went up from 1.25 to about 4 rupees per maund. This was a very high price that few people could afford.

In 1804, the British took complete control of salt in the newly conquered state of Orissa. They gave money to the malangas in advance for future salt production. This made the malangas owe money to the British, almost making them economic slaves. The Orissa zamindars, who had controlled the local salt trade, were worried about losing their income. They tried to convince the malangas not to work for the British, but it didn't work.

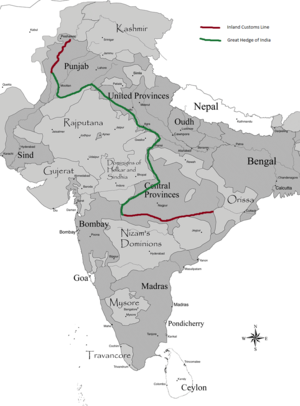

In the early 1800s, to make the salt tax more profitable and reduce smuggling, the East India Company set up customs checkpoints across Bengal. A "customs line" was created, which was a border where high taxes had to be paid for salt transportation. In the 1840s, a thorn fence was built along the western borders of Bengal province to stop salt smuggling. After 1857, this thorn fence grew to be 2,500 miles long.

A customs line was set up, which stretched across all of India. By 1869, it went from the Indus River to the Mahanadi River in Madras, a distance of 2,300 miles. It was guarded by nearly 12,000 men and officers... it was mostly a huge, thick hedge of thorny trees and bushes, with some stone walls and ditches. No person, animal, or vehicle could cross without being stopped and searched.

Salt Taxes Under British Rule

The tax laws started by the British East India Company continued for ninety years under British Raj rule. The fence built to prevent salt smuggling was finished during this time. Records show that by 1858, British India got 10% of its income from its control over salt. However, by the end of the century, the salt tax had been greatly reduced. In 1880, income from salt was 7 million pounds.

In 1900 and 1905, India was one of the world's largest salt producers, making over 1 million metric tons each year.

In 1923, under the leadership of Lord Reading, a law was passed that doubled the salt tax. However, another plan to increase the tax in 1927 was stopped. This doubling of the tax in 1923 was one of the first actions taken by Finance Member Basil Blackett when he presented his first budget.

| Year | Rupees (millions) | Pounds (millions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1929–30 | 67 | 5.025 |

| 1930–31 | 68 | 5.1 |

| 1931–32 | 87 | 6.525 |

| 1932–33 | 102 | 7.65 |

Salt Laws and Their Impact

The first laws to control the salt tax were made by the British East India Company. In 1835, the government set up a salt commission to look at the existing salt tax. It suggested that Indian salt should be taxed so that imported English salt could be sold more easily. Because of this, salt was imported from Liverpool, which made salt prices go up. Later, the government created a monopoly on making salt through the Salt Act. Making salt was made illegal and could lead to six months in prison. The committee also suggested that Indian salt be sold in maunds of 100. However, it was often sold in much smaller amounts. In 1888, the salt tax was increased by Lord Dufferin as a temporary measure. Cheshire salt imported from the United Kingdom was much cheaper. However, Cheshire salt was not as good quality as India's salt. India's salt imports reached 2,582,050 metric tons by 1851.

In 1878, a single salt tax policy was adopted for all of India, including both British-controlled areas and the princely states. Both making and owning salt were made illegal by this policy. The salt tax, which was one rupee and thirteen annas per maund in Bombay, Madras, the Central Provinces, and the princely states of South India, was increased to two rupees and eight annas. In Bengal and Assam, it was decreased from three rupees and four annas to two rupees and fourteen annas. In North India, it was decreased from three rupees to two rupees and eight annas.

Section 39 of the Bombay Salt Act, similar to Section 16-17 of the Indian Salt Act, allowed a salt-revenue official to break into places where salt was being made illegally and take the illegal salt. Section 50 of the Bombay Salt Act stopped salt from being shipped overseas.

The India Salt Act of 1882 included rules that made the government control all collection and making of salt. Salt could only be made and handled at official government salt depots, with a tax of 1 rupee and 4 annas on each maund (82 pounds).

In 1944, the Central Legislative Assembly passed the Excises and Salt Act. This act, though changed in India and Pakistan, is still in use in Bangladesh.

A new salt tax was introduced in the Republic of India through the Salt Cess Act of 1953. This act was approved by the president on December 26, 1953, and started on January 2, 1954.

Then there is a very poor worker, whose income might be thirty-five rupees a year. If he, with his wife and three children, eats twenty-four seers [49 lb] of salt, he has to pay a salt tax of two rupees and seven annas. This is like paying a 7.5 percent income tax. Now, we ask our readers to decide if farmers and workers can get enough salt. We can say from our own experience that a regular farmer can never get more than two-thirds of what he needs, and a worker not more than half.

Early Protests Against the British Salt Tax

Since the British East India Company first introduced salt taxes, the laws were strongly criticized. The Chamber of Commerce in Bristol was one of the first to send a petition against the salt tax:

The price for the customer here [in England] is only about 30 shillings per ton instead of 20 pounds per ton as in India. If it was necessary to remove the Salt tax at home some years ago, your petitioners believe that the millions of Her Majesty's subjects in India have a much stronger reason for it to be removed for them, as they are very poor, and salt is essential for their daily food and to prevent disease in such a climate.

The salt tax was criticized at a public meeting in Cuttack in February 1888. At the first meeting of the Indian National Congress in 1885 in Bombay, a well-known Congress member, S. A. Saminatha Iyer, spoke against the tax:

It would be unfair and wrong if the tax on salt were increased. It is a necessary item for both human and animal health... it would be bad policy and a step backward to raise the tax, especially at a time when the poor millions of India are hoping for a further reduction of the tax... Therefore, since any increase of this tax will greatly affect the common people of the land, I strongly urge this Congress to protest against any attempt by the Government to raise the tax on salt.

At the Allahabad meeting of the Indian National Congress in 1888, Narayan Vishnu, a delegate from Poona, strongly opposed the Indian Salt Act. A resolution was passed where the delegates declared that they disapproved of the recent increase in the salt tax. They said it added a noticeable burden on the poorer classes and was a partial use of the Empire's only financial backup during a time of peace and plenty. The 1892 meeting at Allahabad ended with: "... We do not know when the tax will be reduced. So, it is very necessary for us to repeat this request for the sake of the common people, and we truly hope it will be granted soon." A similar protest was also made at the Congress meeting in Ahmedabad.

The salt tax was also protested by important people like Dadabhai Naoroji. In 1929, Pandit Nilakantha Das asked for the salt tax to be removed in the Imperial Legislature, but his requests were ignored. In 1930, Orissa was almost in open rebellion.

Mahatma Gandhi and the Salt Tax

Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi wrote his first article about the salt tax in 1891 in a magazine called The Vegetarian. While in South Africa, he wrote in The Indian Opinion:

The tax placed on salt in India has always been criticized. This time it has been criticized by the well-known Dr. Hutchinson who says that 'it is a great shame for the British Government in India to continue it, while a similar tax previously in force in Japan has been abolished. Salt is an essential part of our diet. It could be said that the increasing number of leprosy cases in India was due to the salt tax. Dr. Hutchinson considers the salt tax a cruel practice, which does not suit the British Government.

In 1909, Mahatma Gandhi wrote in his book Hind Swaraj from South Africa, asking the British government to get rid of the salt tax.

Mahatma Gandhi's Salt March

At the important Lahore meeting of the Indian National Congress on December 31, 1929, where Purna Swaraj (complete self-rule) was declared, a brief mention was made of the unfair salt law. It was decided that a way should be found to oppose it. In the first week of March 1930, Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Lord Irwin, telling him about the difficult social, economic, and political conditions in the country.

On March 12, 1930, Gandhi started a peaceful protest (satyagraha) with 78 followers from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi on the Arabian Sea coast. This march, known as the Dandi March, got a lot of attention from international news. Videos and pictures of Mahatma Gandhi were sent to far-off parts of the world. Gandhi reached Dandi on April 5, 1930. After his morning bhajan (prayer), he walked into the seashore and picked up a handful of salt. He announced that with that handful of salt, he was declaring the end of the British Empire. The police arrived and arrested thousands of national leaders, including Gandhi. Mahatma Gandhi's brave act of breaking the salt law encouraged other Indians to do the same.

Other Salt Protests (Satyagrahas)

Soon after the Salt satyagraha ended at Dandi, Gandhi planned to lead a group of satyagrahis to the Dharasana Salt Works in Gujarat. But he was arrested by the police. A few days later, Congress leader Abbas Tyabji was also arrested. So, Sarojini Naidu took on the role of leading the marchers at Dharasana. They marched to Dharasana, where they were stopped by a group of police. The non-violent satyagrahis faced the police. About 320 protesters were either killed or badly hurt.

In April 1930, Congress leader Chakravarti Rajagopalachari led a salt satyagraha in Vedaranyam, Madras province. The satyagrahis reached Vedaranyam on the east coast of India on April 28. There, they illegally made salt on April 30.

What Happened Next

The British government ignored the huge protests against the salt tax that shook India in the early 1930s. The Dandi March was only partly successful. Although it forced the British rulers to talk, the salt tax continued. It was only on April 6, 1946, that Mahatma Gandhi formally asked Sir Archibald Rowlands, the finance member of the Viceroy's Executive Council, to remove the unfair salt tax. Rowlands officially issued an order to abolish the salt tax, but the order was stopped by the Viceroy, Lord Wavell. The salt tax remained until March 1947, when it was finally removed by the Interim Government of India led by Jawaharlal Nehru, by the then-Finance Minister Liaquat Ali Khan.

A changed salt tax was later brought back to the Republic of India through the Salt Cess Act of 1953. This act was approved by the President on December 26, 1953, and started on January 2, 1954. This tax, which was 14 paise for every 40 kg of salt produced, was criticized because it collected very little money. The government spent twice as much to collect the tax as it earned from it. This tax was replaced in 2017 by the Goods and Services Tax system, which officially places salt in the 0% taxation category.

In Pakistan, raw table salt is taxed, but iodized salt is not. Salt makers have criticized this because they have to pay tax on the salt they later iodize and sell tax-free.

See also

- Gabelle – French salt tax