History of the Supreme Court of the United States facts for kids

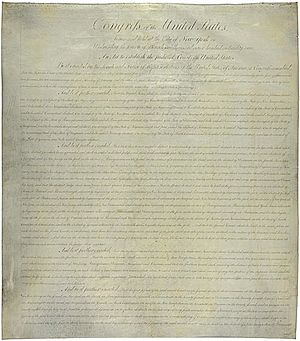

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the U.S. legal system. It's the only court specifically created by the Constitution of the United States, which started in 1789. The first law about the court, called the Judiciary Act of 1789, said it would have six members. Today, there are nine justices, but Congress decides this number, not the Constitution. The Supreme Court first met on February 2, 1790.

Contents

- Early Years: The First Chief Justices (1789–1801)

- The Marshall Court: Shaping the Nation (1801–1835)

- The Taney Court: A Time of Division (1836–1864)

- After the Civil War: Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910)

- Early 20th Century: White and Taft Courts (1910–1930)

- The Great Depression and World War II: Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts (1930–1953)

- The Warren Court: Civil Rights and Liberties (1953–1969)

- The Burger Court: Affirming Rights (1969–1986)

- The Rehnquist Court: A Conservative Shift (1986–2005)

- The Roberts Court: Present Day (2005–present)

Early Years: The First Chief Justices (1789–1801)

The very first Chief Justice of the United States was John Jay. The Court's first official case was Van Staphorst v. Maryland (1791). Its first recorded decision was West v. Barnes (1791).

One of the most talked-about early decisions was Chisholm v. Georgia. In this case, the Court said that people could sue states in federal courts. Many states worried about this. So, Congress quickly suggested the Eleventh Amendment. This amendment stopped certain types of lawsuits against states in federal courts. It was approved in 1795.

After John Jay, John Rutledge became Chief Justice, followed by Oliver Ellsworth. Not many big cases came before the Supreme Court during their time.

The Marshall Court: Shaping the Nation (1801–1835)

One of the most important periods for the Supreme Court was when John Marshall was Chief Justice (from 1801 to 1835).

In a famous case called Marbury v. Madison (1803), Marshall made a huge decision. He ruled that the Supreme Court could strike down a law passed by Congress if it went against the Constitution. This power is called judicial review. It means the Court can check if laws are fair and constitutional.

The Marshall Court also made important decisions about how power is shared between the federal government and the states, known as federalism. Marshall believed the federal government had broad powers. For example, in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Court said Congress could create a national bank. This was allowed even though the Constitution doesn't directly say Congress can create a bank. The Court used the Necessary and Proper Clause to support this. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Court ruled that Congress could control trade and travel between states.

The Marshall Court also limited what state governments could do. It decided that the Supreme Court could hear appeals from state courts. This was set in cases like Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816) and Cohens v. Virginia (1821). The Court also confirmed that federal laws are stronger than state laws. For instance, in McCulloch, the Court said a state couldn't tax a federal government agency.

However, in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the Marshall Court ruled that the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) only applied to the federal government, not to the states. Later, the Court would change this view. They would use the Fourteenth Amendment to apply most parts of the Bill of Rights to the states.

Chief Justice Marshall was a strong leader. He was good at getting his fellow justices to agree. He believed in finding common ground. He was known for his charm and intelligence. He helped shape the Supreme Court into a powerful and respected part of the government.

The Taney Court: A Time of Division (1836–1864)

In 1836, Roger B. Taney became Chief Justice after Marshall. Taney had a more limited view of the federal government's power. During his time, there were many disagreements between the North and South, especially about slavery.

The most controversial decision of the Taney Court was in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). Dred Scott was an enslaved man from Missouri. He sued for his freedom because his owner had taken him to places where slavery was against the law. Chief Justice Taney ruled that African Americans, whether free or enslaved, could not be U.S. citizens. Because of this, he said Scott couldn't even file a lawsuit. Taney also ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. This law had banned slavery in some U.S. territories. This decision angered people who wanted to end slavery and made the tensions leading to the Civil War even worse.

After the Civil War: Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910)

During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln chose Salmon P. Chase to be Chief Justice. Chase was strongly against slavery. After the war, his Court made decisions that helped keep the United States together. In 1869, Congress increased the number of justices to nine.

After the Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed. It said that states could not take away citizens' rights, deny fair legal processes, or treat people unequally. Many cases after the war were about understanding this amendment.

In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Court, led by Chief Justice Morrison Waite, said that the Fourteenth Amendment didn't stop private people or businesses from discriminating. It only applied to governments. Later, in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court, under Chief Justice Melville Fuller, ruled that racial segregation in public places was allowed. They said it was okay as long as the separate facilities were "equal." This led to the famous and unfair idea of "separate but equal." Only Justice John Marshall Harlan disagreed with this decision.

Early 20th Century: White and Taft Courts (1910–1930)

In the early 1900s, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment protected "freedom of contract." This meant people had the freedom to make agreements, like work contracts. Because of this, the Court overturned many state and federal laws that aimed to protect workers. For example, in Lochner v. New York (1905), the Court struck down a New York law that limited how many hours bakers could work.

In 1925, the Supreme Court made an important ruling in Gitlow v. New York. This case started the idea of incorporation. This means that parts of the Bill of Rights, which originally only applied to the federal government, also apply to the states. Gitlow specifically said that the First Amendment's protection of free speech applied to the states. More parts of the Bill of Rights would be applied to the states in later decades, especially in the 1960s.

The Great Depression and World War II: Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts (1930–1953)

During the 1930s, the Supreme Court had both conservative and liberal justices. The conservative justices were sometimes called "The Four Horsemen." The liberal justices were called "The Three Musketeers." Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts were often the "swing votes," meaning their votes decided close cases.

The Court often sided with the conservatives. They overturned many of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs. These programs were designed to help the country recover from the Great Depression. For example, the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act were struck down.

President Roosevelt tried to change the Court's balance in 1937. He proposed a plan to add more justices to the Supreme Court. His goal was to appoint justices who would support his New Deal policies. This plan was called the "court-packing bill" by its opponents. It faced strong opposition and failed in Congress.

However, the Court's balance soon shifted anyway. Justice Roberts started voting differently. Also, some conservative justices retired or passed away. By the end of 1941, Roosevelt had appointed many new justices. This included elevating Harlan Fiske Stone to Chief Justice.

The Hughes and Stone Courts also made important decisions for civil rights. They overturned convictions of African Americans in southern courts. They also helped lay the groundwork for ending school segregation later on. For example, in Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Court outlawed "white primaries." These were elections where only white people could vote. This decision helped more Black Americans register and vote in the South.

The Warren Court: Civil Rights and Liberties (1953–1969)

In 1953, President Dwight David Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren as Chief Justice. Warren's time on the Court, until 1969, was one of the most important in its history. Under his leadership, the Court made many landmark decisions.

The first major case of Warren's time was Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In this case, the Court unanimously declared that segregation (separation) in public schools was unconstitutional. This decision effectively overturned the "separate but equal" rule from Plessy v. Ferguson.

The Warren Court also made important decisions about the Bill of Rights. It applied most of the Bill of Rights' protections to the states. For example, in Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court said that official prayer in public schools was unconstitutional. In Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), it banned mandatory Bible readings in public schools.

The Court also expanded the rights of people accused of crimes.

- In Mapp v. Ohio (1961), the Court ruled that evidence found illegally could not be used in a trial.

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) said that states must provide lawyers for poor defendants.

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966) ruled that police must tell suspects their rights (like the right to remain silent) before questioning them. This led to the famous Miranda warning.

Another important decision was Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). This case established that the Constitution protects a right to privacy.

The Burger Court: Affirming Rights (1969–1986)

Warren E. Burger became Chief Justice in 1969 and served until 1986. The Burger Court made important decisions, especially about the First Amendment. In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), it created the "Lemon test." This test helps decide if a law violates the part of the First Amendment about government not favoring a religion.

The Burger Court also put a temporary stop to the death penalty in Furman v. Georgia (1972). The Court said that death sentences were being given out unfairly. However, the ban was lifted four years later in Gregg v. Georgia (1976).

In United States v. Nixon (1974), the Court ruled that courts have the final say on constitutional questions. It also said that no person, not even the President of the United States, is completely above the law. The Burger Court generally upheld many of the Warren Court's rulings.

The Rehnquist Court: A Conservative Shift (1986–2005)

Chief Justice William Rehnquist led the Court from 1986 until his death in 2005. The Rehnquist Court often took a more limited view of Congress's powers. For example, in United States v. Lopez (1995), it limited Congress's power to regulate things under the commerce clause.

The Court made several controversial decisions during this time:

- Texas v. Johnson (1989) said that burning the American flag was a form of free speech protected by the First Amendment.

- Lee v. Weisman (1992) declared that official, student-led prayers at school events were unconstitutional.

Perhaps the most controversial decision was Bush v. Gore (2000). This ruling stopped the vote recounts in Florida after the 2000 presidential election. This allowed George W. Bush to become president.

The Rehnquist Court was very stable. For 11 years, from 1994 to 2005, the same nine justices served together. This was the longest such period in over 180 years.

The Roberts Court: Present Day (2005–present)

John G. Roberts became Chief Justice on September 29, 2005. He led the Court for the first time on October 3, 2005. Since then, the Court has generally moved in a more conservative direction. This can be seen in cases about the death penalty and campaign finance.

In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the Supreme Court made a very important decision about the Second Amendment. It ruled that the Second Amendment protects an individual's right to own a gun for self-defense at home.

Since 2009, several new justices have joined the Court:

- In 2009, Sonia Sotomayor became the first Hispanic-American justice.

- In 2010, Elena Kagan joined the Court.

- In 2017, Neil Gorsuch was confirmed.

- In 2018, Brett Kavanaugh joined.

- In 2020, Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed shortly before the presidential election.

- In 2022, Ketanji Brown Jackson became the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court.

In March 2020, the Supreme Court postponed oral arguments because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was the first time its operations were disrupted in 102 years.

On November 13, 2023, the Court issued its first-ever Code of Conduct for Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. This set out clear ethics rules for the justices.

|

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |