Hittites facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hittite Empire

𒄩𒀜𒌅𒊭 (Ḫattuša)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1650 BC–c. 1180 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Royal seal of the king Šuppiluliuma I and Tawananna

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Map of the Hittite Empire at its largest extent, with Hittite rule c. 1300 BC

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital-in-exile | Šamuḫa (1400–1350 BC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Hittite, Hattic, Luwian, Akkadian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hittite religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1650 BC

|

Labarna I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1210–1180 BC

|

Šuppiluliuma II (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | The Pankus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 1650 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

c. 1180 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Estimate

|

200,000+ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Barter Economy, Gold, Copper, Silver and Bronze common barter items of value. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Hittites were a powerful people who built one of the great empires of the ancient Bronze Age. They lived in a region called Anatolia, which is in modern-day Turkey. The Hittite Empire began around 1650 BC and became a major power in the Middle East.

At its peak in the 14th century BC, the Hittite Empire was huge. It covered most of Anatolia and parts of Syria and Mesopotamia. The Hittites were famous for their skilled warriors, who used horse-drawn chariots in battle. They often fought with other great powers like Egypt and Assyria.

The Hittites spoke one of the oldest known Indo-European languages. We know about them today because archaeologists have found thousands of clay tablets with their writing on them. These tablets tell us about their history, laws, and religion.

Around 1180 BC, the Hittite Empire collapsed during a time of chaos known as the Late Bronze Age collapse. After the empire fell, smaller Hittite states survived for a few hundred years. Eventually, the Hittite people mixed with other groups in the region.

Contents

Discovering the Lost Empire

For a long time, people only knew about the Hittites from mentions in the Bible. But in the 19th century, explorers and archaeologists began to find amazing ruins in Turkey.

In 1834, a French scholar named Charles Texier found the ruins of the Hittite capital, Hattusa. He didn't know what he had found at the time. Later, other discoveries helped solve the puzzle. Archaeologists found clay tablets in Egypt that mentioned a "kingdom of Kheta." These were letters between the Egyptian pharaohs and the Hittite kings.

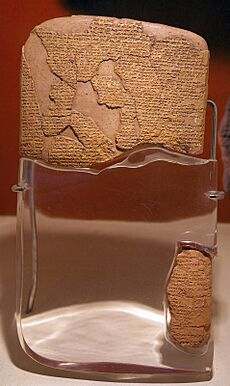

The biggest breakthrough came in 1906. An archaeologist named Hugo Winckler began digging at Hattusa and found a royal archive. It contained 10,000 clay tablets written in cuneiform, the script used across the ancient Middle East. Some tablets were in a known language, Akkadian, but others were in a mysterious language. This language turned out to be Hittite.

Solving the Language Puzzle

The Hittite language was a mystery until a Czech scholar named Bedřich Hrozný figured it out. In 1915, he announced that he had deciphered the language. He proved it was an Indo-European language, related to languages like Latin, Greek, and English. This was a huge discovery. It meant Hittite was the oldest recorded language in this family.

History of the Hittite Empire

The history of the Hittites is often divided into three main periods: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom.

The Old Kingdom (c. 1650–1500 BC)

The Hittite Kingdom was founded by a king named either Labarna I or Hattusili I. Hattusili made the city of Hattusa his capital. He and his grandson, Mursili I, were strong military leaders. They expanded the kingdom by conquering nearby lands.

Mursili I led a daring raid all the way down the Euphrates River and captured the great city of Babylon in 1595 BC. This was a huge victory, but it stretched the Hittite army thin. Soon after, Mursili was killed by his brother-in-law, and the kingdom fell into a period of chaos. Kings fought each other for the throne, and the empire weakened.

The Middle Kingdom (c. 1500–1430 BC)

This was a difficult time for the Hittites. Not much is known about this period because few records have survived. The kingdom was smaller and had to deal with constant attacks from enemies, especially the Kaskians from the north.

The New Kingdom (c. 1430–1180 BC)

The Hittite Empire came back stronger than ever during the New Kingdom. This is also called the Hittite Empire period. The kings became more powerful and were seen as god-like figures, called "My Sun" by their people.

A king named Šuppiluliuma I (who ruled around 1350 BC) was a brilliant general and politician. He conquered much of Syria and turned the rival kingdom of Mitanni into a vassal state (a state controlled by the Hittites). Under his rule, the Hittite Empire became one of the three great powers of the world, along with Egypt and Assyria.

The Battle of Kadesh

One of the most famous events in Hittite history is the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC. The Hittite army, led by King Muwatalli II, fought the Egyptian army, led by Pharaoh Ramesses II. Both sides had thousands of chariots.

The battle was huge and bloody, but neither side won a clear victory. The Egyptians claimed they won, and Ramesses II covered his temples with carvings of his "victory." However, the Hittites also claimed success. Years later, the Hittites and Egyptians signed the world's first known peace treaty, the Treaty of Kadesh. A copy of this treaty is now in the United Nations headquarters as a symbol of peace.

The Fall of the Empire

After the Battle of Kadesh, the Hittite Empire began to face new problems. The powerful Assyrian Empire was growing in the east and taking Hittite lands. At the same time, mysterious groups of invaders called the Sea Peoples were attacking cities along the Mediterranean coast.

These attacks cut off the Hittites' important trade routes. Around 1180 BC, the capital city of Hattusa was attacked and burned to the ground. This marked the end of the great Hittite Empire. This collapse was part of a wider event called the Bronze Age Collapse, when many great civilizations in the region fell.

After the empire fell, smaller kingdoms known as the Syro-Hittite states appeared in Syria and southern Anatolia. They kept Hittite culture alive for several more centuries before they were eventually conquered by the Assyrians.

Government and Law

The Hittite king was the head of the government. He was the top general, the highest judge, and the high priest. However, he did not have total power, especially in the early days.

The Pankus

In the Old Kingdom, the king was advised by an assembly of nobles called the Pankus. The Pankus could even put the king on trial if he committed a serious crime. This shows that the Hittites had a form of constitutional monarchy, where the king's power was limited by laws. Later, in the New Kingdom, the king became much more powerful, and the Pankus lost its influence.

The Hittite Laws

The Hittites were known for their advanced legal system. Archaeologists have found tablets with their laws written on them. Unlike other kingdoms in the region that had very harsh punishments, Hittite laws were often more humane.

For many crimes, like theft, the punishment was not death but restitution. This meant the criminal had to pay back the victim for what was stolen, often with an extra fine. The laws were designed to be fair and to keep society in order. They made distinctions between crimes that were accidents and crimes that were done on purpose.

Religion and Mythology

The Hittites worshipped many gods and goddesses. They called their religion "the religion of a thousand gods" because they often adopted gods from the peoples they conquered, like the Hurrians and Hattians.

Their most important god was the Storm God, known as Tarhunt. He controlled the thunder, lightning, and rain, which was very important for farming. He was often shown as a strong, bearded man holding a club and standing on two mountains.

The Hittites held many religious festivals throughout the year to honor their gods. During these festivals, they would carry statues of the gods through the streets in big parades.

Art and Architecture

The Hittites were skilled builders and artists. Their capital, Hattusa, was protected by massive stone walls with impressive gates, like the Lion Gate and the Sphinx Gate.

They carved large reliefs (pictures carved into rock surfaces) on cliffs and monuments. A famous example is the rock sanctuary of Yazılıkaya, near Hattusa. The walls are covered with carvings of their gods and goddesses.

Hittite artists also made beautiful objects from metal, ivory, and clay. Some of the most famous artifacts are the Alaca Höyük bronze standards, which are detailed figures of stags and bulls made of bronze.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hatti para niños

In Spanish: Hatti para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |