Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mammoth Internal Improvement Act |

|

|---|---|

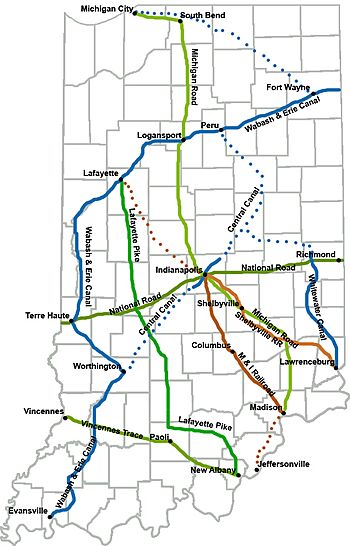

Map showing the extent of the projects along with portions that were not completed by the state

|

|

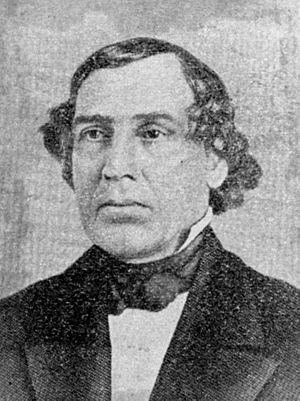

| Enacted by | Governor Noah Noble |

| Date signed | 1836 |

The Mammoth Internal Improvement Act was a big law passed in Indiana in 1836. It was signed by Governor Noah Noble. This law aimed to greatly expand Indiana's transportation system. It planned to build many new turnpikes (toll roads), canals, and railroads.

The state borrowed $10 million for these projects. This was a huge amount of money back then. Unfortunately, a financial crisis called the Panic of 1837 hit soon after. This caused big problems for Indiana's economy. The state almost went bankrupt because of the debt.

By 1841, Indiana could not even pay the interest on its loans. Most projects were given to the state's lenders in London. This reduced the debt by half. Later, in 1846, the last big project was also given away. None of the eight projects were fully finished by the state. Only two were completed by the lenders who took them over.

This act is seen as one of the biggest failures in Indiana's history. People blamed the Whig party, who were in charge at the time. The financial disaster led to the Whig party losing power in Indiana. Despite these problems, the projects did help Indiana in the long run. Land values increased a lot. The Wabash and Erie Canal, partly funded by the act, became the longest canal in North America.

Contents

Why Indiana Needed Better Transportation

When Indiana became a state in 1816, it was mostly wilderness. Most people lived near the Ohio River. This river was the main way to ship goods. There were very few good roads. The Vincennes Trace was an old dirt trail used by bison. It was the only major path across the southern part of the state.

Early plans were made to improve travel. These included small local roads and the larger Michigan Road. There was also an attempt to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio. But a financial crisis in 1819 caused the state's banks to fail. This stopped early improvement plans.

Early Canal Efforts

In the 1820s, Indiana worked to fix its money problems. The state asked the U.S. Congress for help with transportation. Other states like New York and Pennsylvania were building canals. They wanted to connect to the Mississippi River system through Indiana.

In 1824, Congress gave Indiana a strip of land 320 feet (98 m) wide. This land was for building a canal. But Indiana had to start building within twelve years. Many in Indiana thought this was not enough land. They wanted a wider strip, but Congress did not agree. People living near the Ohio River opposed the canal. They felt it would not benefit them, but they would have to pay for it.

In 1827, Congress made a new offer. They gave Indiana a half-mile wide strip of land. They also offered money to help build the canal. This time, Indiana accepted. In 1828, a commission was set up to plan the canal route. But no state money was approved yet. The commission planned a short six-mile (9.7 km) canal. This became the start of the Wabash and Erie Canal.

Funding was still a problem. The lowest cost estimate was $991,000. Southern Indiana still preferred a canal in the Whitewater Valley. Governor James B. Ray thought canals were a waste of money. He wanted railroads instead. He even threatened to stop any canal project. Because the state would not help pay, the project relied on federal funds. It also used money from selling land next to the canal route. Construction finally began in 1831.

The National Road and State Bank

In 1829, the National Road entered Indiana. This large highway was paid for by the federal government. By 1834, opposition to the canal had disappeared. The Wabash and Erie Canal was being built with little cost to the state. It was also starting to make money. So, the General Assembly gave funds to connect it to Lafayette.

To help pay for this, Indiana created the Bank of Indiana. Bonds were sold through this bank to lenders in London. This helped fund the early stages of the canal. But it soon became clear that much more money would be needed.

The Mammoth Act is Passed

In 1836, Indiana lawmakers decided to greatly expand the state's improvement plans. At first, they only wanted to keep funding the Wabash and Erie Canal. But many lawmakers opposed this. They felt it would not help their own areas.

So, they agreed on a compromise. More projects were added so that all major cities would get a canal, railroad, or turnpike.

- The Vincennes Trace was to be paved.

- A Lafayette Turnpike was approved.

- The Michigan Road was also to be paved.

- Two railroads were approved: one from Lawrenceburg to Indianapolis, and another from Madison to Lafayette.

- Funding was added for a canal in the Whitewater Valley.

- A Central Canal was also funded to connect Indianapolis to the new canals.

Over $2 million had already been borrowed. The new bill proposed borrowing another $10 million. This was added to $3 million from land sales. Lawmakers believed these projects would make a lot of money for the state. They thought the income would quickly pay back the loans.

At the time, Indiana's yearly tax income was less than $65,000. The new debt was much larger than all the taxes the state had ever collected. The amount borrowed was equal to one-sixth of all the wealth in the state. Even with this huge plan, some lawmakers from the Ohio River counties still opposed it.

The bill called for several canals:

- The Indiana Central Canal from Indianapolis to Evansville on the Ohio River.

- The Whitewater Canal from the Wabash River in Peru to the Ohio River in Lawrenceburg.

- More money for the Wabash and Erie Canal to expand to Terre Haute.

Canals received most of the money. People thought canals could be built with local materials. This would help the local economy. However, later studies showed that some areas were not good for canals. The projects were likely to fail from the start. But the state did not do surveys before passing the bill.

The bill also funded railroads and turnpikes:

- A railroad from Madison to Indianapolis.

- Another railroad from Shelbyville to Indianapolis.

- Paving the Vincennes Trace (renamed the Vincennes Trace).

- Paving the rest of the Michigan Road.

Most of the money came from mortgaging nine million acres of state land. This was done through agents of the Bank of Indiana. The loans came from lenders in London and New York.

Governor Noah Noble strongly supported the bill. It passed easily in the General Assembly, which was mostly Whig. However, some important lawmakers like Dennis Pennington and James Whitcomb opposed it. Pennington thought canals were a waste and would soon be replaced by railroads. Whitcomb simply felt the state could not pay back such a large sum.

Despite the opposition, the bill's passage was celebrated across the state. Citizens saw it as a way to modernize Indiana. Governor Noble considered it his greatest achievement. But he was worried that the assembly had not approved a 50% tax increase he said was needed to pay the debt.

The bill created two groups to manage the projects. These were the Board of Improvement and the Board of Funds Commissioners. Two-thirds of the money went to canals. The Central Canal received the most. Jesse L. Williams was named the chief engineer.

Building the Projects and Facing Problems

From the very beginning, problems arose. The different projects did not work together. Instead, they competed for money and land. Trying to build all projects at once also caused a shortage of workers. This made labor costs much higher than expected. The government had not provided enough money to finish each project. They expected the projects to start making money and fund their own completion.

Governor David Wallace tried to make the commission build one route at a time. This would save money and avoid a financial disaster. But the different groups in the General Assembly could not agree on which line to finish first.

The Wabash and Erie Canal was the most successful canal project. It made money early on, but not as much as hoped. The Central Canal was a big failure. Only a few miles were dug near Indianapolis before the money ran out. The Whitewater Canal was going well until muskrats burrowed through its walls. This caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage. There was no money for repairs. At its peak, over ten thousand workers were employed on the canal projects.

The railroad from Madison to Indianapolis was cheaper to build than the canals. It was given $1.3 million. However, it went over budget. This was because it needed a big slope built to get from the low Ohio Valley up to Indiana's higher land. So, the project could not be finished. If it had started in Indianapolis, it could have earned money from freight and passengers on the flat central Indiana part. This income could have helped fund the difficult part near Madison.

The Vincennes Trace was paved from New Albany to Paoli. This cost $1,150,000. Another 75 miles (121 km) still needed paving when the money ran out.

The Financial Crisis

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis. It was mainly caused by land speculation in the west. This left Indiana in a very bad financial situation. State income shrank. In 1838, Indiana's tax income was $45,000. But the interest on its growing debt was $193,350.

Governor Wallace reported this shocking news to the General Assembly. They argued about what to do. They decided to make debt payments by borrowing even more money. They hoped the projects could be finished before the state ran out of credit. This gamble did not pay off. By 1839, there was no money left for the projects, and work stopped.

Work only continued on the Wabash and Erie Canal. Workers were paid with stock in the canal, not cash. Supplies were bought using federal money. At this point, 140 miles (230 km) of canal had been built for $8 million. Also, $1.5 million had been spent on 70 miles (110 km) of railroad and turnpike. The state was left with a $15 million debt. Its tax income was just a small trickle.

To try and get more money, the state changed how property taxes were assessed. Taxes were now based on property values, not a set amount per acre. This small change increased income by 25% the next year. But it was still nowhere near enough to cover the debt. Governor Wallace announced that the state would be unable to pay its debts within a year. The 1841 budget had over $500,000 in debt payments. But income that year was only $72,000. Indiana was unofficially bankrupt.

The people who supported the projects had promised that taxes would not need to increase. They even said that once the projects were finished, taxes might be removed. This was because tolls would pay for all the state's needs. Because of this, no plans had been made to pay the interest on the huge debt.

In 1841, Governor Samuel Bigger suggested creating county boards to set property values. This new system led to tax increases of up to 400% in some areas. Citizens protested these harsh tax hikes. Many refused to pay. The General Assembly had to cancel the system the next year.

Negotiating the Debt

James Lanier, president of the Bank of Indiana, was sent to London. Governor Bigger hoped he could negotiate with the state's lenders. In 1841, he negotiated a deal. All projects, except the Wabash and Erie Canal, were given to the lenders. In return, the debt they held was cut by 50%. This lowered the total state debt to $9 million.

Even with less debt, the payments were still too much for Indiana. On January 13, 1845, the General Assembly issued an official apology. They apologized to the state's lenders and the U.S. government for not paying parts of their debt. This apology stated that breaking promises was wrong. It said that any state that did not honor its agreements would lose respect. The governor was told to send copies of the apology to every state. This failure ruined Indiana's credit for almost twenty years.

The Whig party suffered greatly from the project's failure. James Whitcomb, who had opposed the projects from the start, was elected governor. A Democratic majority had already taken control of the statehouse the year before. With their support, he began talks to end the crisis.

Charles Butler came from New York in 1846 to negotiate for the state's lenders. The deal was for Indiana to give up most ownership of the Wabash and Erie Canal. In return, the debt would be cut by another 50%. This left the state owing $4.5 million and ended the financial crisis. Even though the debt was much lower, payments were still over half of the state budget. But Indiana's population was growing, which quickly raised tax income.

What Happened Next

The lenders took over the public works. They expected to finish them quickly and make money. But they were disappointed. Not all projects were profitable.

- The Vincennes Trace was renamed the Paoli Pike. It operated as a private toll road for several years. It was later bought back by the state. Its tolls covered its costs, but it never made a profit.

- The Central Canal was completely abandoned. It was too expensive to finish. Also, the area was not suitable for canals.

- The Whitewater Canal was about one-fifth finished. The existing part was used until 1847. Then, a section collapsed, making the northern part unusable. The southern part was used until 1865. It closed after losing business to a nearby railroad.

- The Wabash and Erie Canal was finally completed in 1848. It operated for 32 years. But the higher parts of the canal in central Indiana needed a lot of maintenance. Muskrats often damaged them. High upkeep costs and competition from railroads led to the canal's company failing in the 1870s.

- The railroad from Madison to Indianapolis was also abandoned by the lenders. It was sold to a group of business people. They raised money to finish the line. The Madison & Indianapolis Railroad immediately made money. It expanded and connected to other cities.

Today, only a fifteen-mile (24 km) restored section and a few ponds remain of the Wabash and Erie Canal. Much of the canal land was sold to railroad companies. This land was excellent for building rail lines. The turnpikes and railroads turned out to be the most successful projects. Some parts of them are still used today.

Even though the government lost millions, there were big benefits for areas where the projects succeeded. On average, land value in Indiana rose by 400%. The cost of shipping goods for farmers dropped a lot. This increased their profits. The investors in the Bank of Indiana also made good money. These investments helped start a modern economy for the state. The Mammoth Internal Improvement Act is often seen as the biggest legislative failure in Indiana's history.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |