Indonesian occupation of East Timor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Indonesian occupation of East Timor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War (until 1991) | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

East Timorese Resistance Groups

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250,000 troops | 27,000 (including non combatant in 1975) 1,900 (including non combatant in 1999) 12,538 fighters (1975–1999) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,277 soldiers and police killed 1,527 Timorese militia killed 2,400 wounded Total: 3,408 killed and 2,400 wounded |

11,907 fighters killed (1975–1999) | ||||||

| Estimates range from 100,000–300,000 civilians dead (see below) | |||||||

The Indonesian occupation of East Timor was a period when Indonesia controlled East Timor. It started in December 1975 and lasted until October 1999. Before this, East Timor had been a colony of Portugal for many centuries.

In 1974, a big change in Portugal's government led to its colonies becoming independent. This caused some trouble in East Timor, and its future became unclear. After a small fight between different groups in East Timor, a group called Fretilin declared East Timor independent on 28 November 1975.

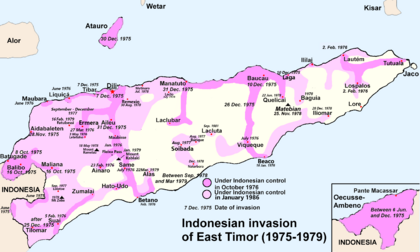

Soon after, on 7 December 1975, Indonesian military forces entered East Timor. By 1979, they had mostly stopped the groups fighting against them. On 17 July 1976, Indonesia officially made East Timor its 27th province, calling it Timor Timur.

Right after Indonesia moved in, the United Nations said Indonesia's actions were wrong. They asked Indonesia to leave East Timor. Only Australia and Indonesia officially recognized East Timor as part of Indonesia. Other countries like the United States and Japan also supported Indonesia's government. However, Indonesia's actions in East Timor hurt its reputation around the world.

For 24 years, the Indonesian government treated the people of East Timor very harshly. Many people were put in camps, and many died from violence or not enough food. But people in East Timor kept fighting for their freedom. In 1996, two East Timorese men, Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and José Ramos-Horta, won the Nobel Peace Prize. They received it for their peaceful efforts to end the occupation.

In 1999, people in East Timor voted to decide their future. Most people voted for independence. East Timor officially became an independent country in 2002. A group called the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor later estimated that between 90,800 and 202,600 people died during the occupation.

After the 1999 vote, groups working with the Indonesian military caused a lot of damage. They destroyed most of the country's buildings and roads. An Australian-led force, the International Force for East Timor, then helped bring back order. After Indonesian forces left, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor managed the area for two years. They set up a special group to look into crimes committed in 1999.

Some universities, like Oxford University and Yale University, teach about this time as a terrible event where many people were killed because of who they were.

Contents

East Timor's Past

Portuguese explorers first arrived in Timor in the 1500s. By 1702, East Timor was officially under Portuguese control. Portugal's rule was not very strong until the island was divided with the Dutch Empire in 1860. During World War II, East Timor was a major battleground. About 20,000 Japanese troops occupied it. The fighting helped stop Japan from taking over Australia, but it led to 60,000 East Timorese deaths.

When Indonesia became independent after World War II, it did not claim East Timor. Indonesian leaders said they had no plans to take over Portuguese Timor. Even after Suharto became Indonesia's leader in 1965, these promises continued. An Indonesian official said in 1974, "Indonesia has no plans to take over Portuguese Timor."

In 1974, the "Carnation Revolution" in Portugal changed things. This event led to Portugal starting to let its colonies become independent. East Timor was one of these colonies. The new Portuguese government began to open up the political process in East Timor.

Political Groups Emerge

When political parties were allowed in East Timor in April 1974, three main groups appeared.

- The União Democrática Timorense (Timorese Democratic Union, or UDT) was formed in May. It was made up of wealthy landowners. At first, UDT wanted East Timor to stay connected to Portugal. But later, it supported full independence.

- The Frente Revolucionária de Timor-Leste Independente (Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, or Fretilin) appeared a week later. This group supported "socialism" and "the right to independence." As things got more tense, Fretilin called itself "the only true voice of the people."

- The Associacão Popular Democratica Timorense (Timorese Popular Democratic Association, or APODETI) was created at the end of May. This group wanted East Timor to join Indonesia. APODETI worried that an independent East Timor would be too weak.

Some Indonesian military leaders saw Portugal's changes as a chance to bring East Timor into Indonesia. They worried that an independent East Timor, especially if led by left-wing groups, could cause problems for Indonesia. They also feared it might inspire other parts of Indonesia to seek independence. Indonesian military intelligence first tried to get East Timor to join Indonesia without fighting. They planned to use APODETI for this.

In January 1975, UDT and Fretilin formed a group to work for East Timor's independence. At the same time, Indonesia's military held a "pre-invasion" exercise. For months, Indonesian special forces secretly supported APODETI. They spread rumors that Fretilin leaders were communists. This caused problems between UDT and Fretilin. Observers said Indonesia was trying to create a reason to invade. By May, UDT left the group it had formed with Fretilin.

To try and solve the problem, Portugal held a meeting in June 1975. Fretilin did not attend this meeting. Fretilin leader José Ramos-Horta later said this was a mistake.

Civil War and Independence

Tensions grew very high in mid-1975. In August 1975, UDT tried to take control in the capital city, Dili. A small civil war began. About 2,000 to 3,000 people died in this fighting. The fighting forced the Portuguese government to a nearby island. Fretilin defeated UDT's forces after two weeks. UDT leaders then fled to Indonesian-controlled West Timor. There, they signed a paper asking for East Timor to join Indonesia. Most people believe Indonesia forced UDT to sign this.

After Fretilin gained control, they faced attacks from the west. These attacks came from Indonesian military forces and a small group of UDT troops. Indonesia captured the border city of Batugadé on 8 October 1975. Nearby Balibó and Maliana were taken eight days later. During the attack on Balibó, five Australian TV news reporters were killed by Indonesian soldiers. These deaths brought international attention to East Timor.

In November, Indonesia and Portugal met to talk about the conflict. No East Timorese leaders were invited. Fretilin sent a message saying they wanted to work with Portugal. But the talks did not lead to a solution. Indonesian forces then began attacking the city of Atabae. They captured it by the end of November.

Fretilin leaders felt Portugal was not doing enough. They believed declaring independence would help them fight Indonesia better. On 28 November 1975, Fretilin declared East Timor an independent country. Indonesia then announced that UDT and APODETI leaders would declare their region part of Indonesia. This was called the Balibo Declaration. However, it was written by Indonesian intelligence and signed in Bali. Many people later called it the 'Balibohong Declaration,' meaning 'Balibo-lie.' Portugal rejected both declarations. The Indonesian government then decided to use military force to take over East Timor.

The Invasion Begins

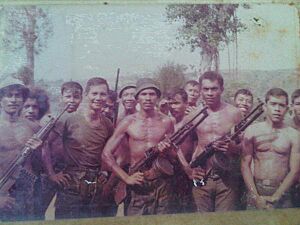

On 7 December 1975, Indonesian forces invaded East Timor. This was Indonesia's largest military operation ever. Fretilin's fighters, called Falintil, fought Indonesian troops in the streets of Dili. Some reports said 400 Indonesian paratroopers were killed. Indonesian reports said 35 Indonesian troops died, and 122 from Fretilin. By the end of 1975, 10,000 Indonesian troops were in Dili, and another 20,000 were across East Timor. Falintil troops were greatly outnumbered. They fled to the mountains and continued to fight using guerrilla tactics.

Indonesia Takes Control

On 17 December, Indonesia set up a temporary government for East Timor. Most people saw this government as a creation of the Indonesian military. This government then formed a "Popular Assembly." This assembly asked to officially join Indonesia. Jakarta called this "the act of self-determination" for East Timor.

Indonesia kept East Timor mostly closed off from the world. They said most East Timorese supported joining Indonesia. Indonesian media also reported this, so most Indonesians believed it. East Timor became a place where Indonesian officers learned how to control people.

Fighting the Resistance

Indonesian leaders first thought taking over East Timor would be quick and easy. But the fighting that followed was very hard for the East Timorese. It also cost Indonesia a lot of money and hurt its image around the world.

By late 1976, neither Falintil nor the Indonesian army could win. Indonesia's army started getting new weapons. They bought missile boats and submarines from other countries. In 1977, Indonesia also received thirteen OV-10 Bronco aircraft from the United States. These planes were good for fighting in mountains. They helped the Indonesian military find Fretilin. The planes attacked Falintil forces with bombs and a chemical called 'Opalm'. Along with new weapons, 10,000 more troops were sent to East Timor. These new attacks were called the 'final solution'.

Indonesia's military started a new plan in September 1977. They aimed to make central East Timor unlivable. They used napalm attacks, chemical warfare, and destroyed crops. This was to force people to surrender and to stop Falintil from getting food. Catholic leaders in East Timor called this plan an "encirclement and annihilation" campaign. About 35,000 Indonesian troops surrounded areas where Fretilin was supported. They killed many civilians. Air and naval attacks were followed by ground troops. These troops destroyed villages and farms. Thousands of people may have died during this time.

During this period, there were reports that Indonesia used chemical weapons. Villagers said maggots appeared on crops after bombings. Fretilin radio claimed Indonesian planes dropped chemical agents. The UN's truth commission later confirmed that Indonesia used chemical weapons and napalm. They poisoned food and water in areas controlled by Fretilin.

This harsh campaign in 1977–1978 weakened the main Fretilin forces. The Fretilin president and military leader, Nicolau Lobato, was killed by Indonesian troops on 31 December 1978.

Forced Relocation and Starvation

Because their food crops were destroyed, many civilians had to leave the hills and surrender. Often, when villagers came down to surrender, the military would kill them. Those who were not killed were sent to special camps. In these camps, people were registered and questioned. Anyone suspected of helping the resistance was killed.

These camps often had no toilets. The Indonesian military also stopped the Red Cross from giving help. No medical care was given. Many Timorese, already weak from hunger, died from not enough food or from diseases like cholera. By late 1979, between 300,000 and 370,000 Timorese had been in these camps. After three months, people were moved to "strategic hamlets." Here, they were kept like prisoners and faced forced starvation. They could not travel or farm.

The UN truth commission confirmed that the Indonesian military used starvation as a weapon. They said many people were "positively denied access to food." The report said this led to the deaths of 84,200 to 183,000 Timorese. One church worker reported that 500 East Timorese died of starvation every month in one area.

In 1978, a group called World Vision Indonesia said 70,000 East Timorese were at risk of starvation. The Red Cross reported in 1979 that 80% of people in one camp were malnourished. They warned that "tens of thousands" were at risk.

Operation Security: 1981–82

In 1981, the Indonesian military started "Operation Security." Some called it the "fence of legs" program. Indonesian forces forced 50,000 to 80,000 Timorese men and boys to march through the mountains. They walked ahead of Indonesian troops as human shields. This was to stop Fretilin from attacking. The goal was to push the fighters into a central area to destroy them. Many of those forced to march died from hunger or tiredness. This operation did not crush the resistance. Instead, it made people hate the occupation even more.

Operation Clean-Sweep: 1983

Indonesia's military commander in Dili started peace talks with Fretilin leader Xanana Gusmão in March 1983. But when Xanana wanted Portugal and the UN to join the talks, Indonesia broke the ceasefire. They started a new attack called "Operational Clean-Sweep" in August 1983. An Indonesian general said, "This time no fooling around. This time we are going to hit them without mercy."

After the ceasefire ended, there were more killings and "disappearances" by Indonesian forces.

Changes to Life and Economy

The Portuguese language was banned in East Timor. Indonesian became the language for government, schools, and business. Indonesian school lessons were used. The Indonesian national idea, Pancasila, was also taught. Government jobs were only for those who had studied Pancasila.

East Timorese traditional beliefs did not fit with Indonesia's official religion. This led to many people becoming Christian. Indonesian priests replaced Portuguese ones. Latin and Portuguese church services were replaced by Indonesian ones. Before the invasion, only 20% of East Timorese were Catholic. By the 1980s, 95% were Catholic. Today, East Timor is one of the most Catholic countries in the world.

East Timor was a special focus for Indonesia's program to move people. This program aimed to move Indonesians from crowded areas to less crowded ones. News about the conflict in East Timor was kept secret. So, many poor Indonesian farmers who moved there did not know about the fighting. They often faced attacks from East Timorese fighters. They also faced anger because large areas of East Timorese land were taken by the Indonesian government for these new settlers.

Many migrants went back home. But those who stayed helped make East Timor more Indonesian. By the mid-1990s, about 150,000 free Indonesian settlers lived in East Timor. This included people who got jobs in schools and government. This migration increased anger among Timorese.

After the invasion, Indonesian businesses took over Portuguese businesses. The border with West Timor opened. This led to many West Timorese farmers coming in. In 1989, East Timor was opened to private investment.

Indonesian business people came to control trade in the towns. East Timor's products were sold through partnerships between army officials and Indonesian business people. A military-controlled company called Denok controlled profitable businesses. This included exporting sandalwood, hotels, and importing goods. Their most profitable business was controlling coffee exports. Coffee was East Timor's most valuable crop. Indonesian business people came to control other businesses too. Local products from the Portuguese time were replaced by Indonesian imports.

The Indonesian government said it was helping East Timor by funding health, education, and transportation. But East Timor remained poor. Critics said that new roads were often built to help the Indonesian military and businesses. Even with improvements, a 1993 Indonesian report said that in three-quarters of East Timor's areas, more than half the people lived in poverty.

The 1990s

Changing Resistance

Even with Indonesia's investments, East Timorese people kept fighting Indonesian rule. By the 1980s, Fretilin had only a few hundred armed men. But Fretilin started to connect with young Timorese, especially in Dili. A peaceful resistance movement began to grow. Many young people had grown up under Indonesian rule. They did not like the control and the loss of Timorese culture. They spoke Portuguese among themselves, showing their Portuguese heritage. They saw Indonesia as an occupying force.

Abroad, Fretilin members, like José Ramos-Horta, spoke about their cause to other countries.

In 1988, Indonesia's government opened East Timor to improve business. They also allowed journalists to travel there. This new policy aimed to address international concerns. In late 1989, a strict military commander was replaced by one who promised a "more persuasive" approach. Travel limits were reduced, and some political prisoners were released. In February 1990, an Indonesian soldier was punished for bad behavior. This was the first time since the invasion.

Less fear of punishment encouraged the resistance. Protests happened during important visits to East Timor. This included the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1989. Also, the end of the Cold War meant Western countries had less reason to support Indonesia. This put more international pressure on Indonesia. Events in East Timor in the 1990s brought more attention to the issue. This helped the resistance groups.

Santa Cruz Massacre

On 12 November 1991, a memorial service was held for a young person killed by Indonesian troops. During the service, about 2,500 people marched. They showed the Fretilin flag and banners with independence slogans. They chanted loudly but peacefully. After a short fight between Indonesian troops and protesters, 200 Indonesian soldiers fired into the crowd. At least 250 Timorese were killed.

Foreigners at the cemetery quickly told international news groups. Video of the massacre was shown worldwide, causing great anger. People around the world started groups to support East Timor. This brought new urgency to calls for independence. Groups like TAPOL in Britain and the East Timor Action Network in the United States grew. Other groups appeared in Portugal, Australia, and Japan.

News of the massacre showed that Indonesia's government was finding it harder to control information. In the 1990s, the government faced more international scrutiny. Some student groups in Indonesia also began to openly discuss East Timor and Indonesia's government.

Strong criticism came from outside and inside Indonesia. The massacre ended the government's open policy. A new period of harsh control began. The military commander who had been more open was removed. People suspected of supporting Fretilin were arrested. Human rights problems increased. Foreign journalists were again banned.

Hatred for the Indonesian military grew stronger among Timorese. Major General Prabowo's special forces trained groups of fighters to crush the remaining resistance.

Xanana Gusmão Arrested

On 20 November 1992, Fretilin leader Xanana Gusmão was arrested by Indonesian troops. In May 1993, he was sentenced to life in prison. Later, his sentence was changed to 20 years. The arrest of the resistance leader was a big blow. But Gusmão remained a symbol of hope from inside Cipinang prison. Peaceful resistance by East Timorese continued. In 1994, when US President Bill Clinton visited Indonesia, 29 East Timorese students occupied the US embassy. They protested US support for Indonesia.

Human rights groups also pointed out ongoing problems. A 1995 report said that "abuses in the territory continue to mount."

Nobel Peace Prize

In 1996, East Timor gained world attention. Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and José Ramos-Horta won the Nobel Peace Prize. They won it "for their work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor." The Nobel Committee hoped the award would help find a peaceful solution.

For Indonesia, the prize was embarrassing. The government tried to separate the two winners. They recognized Bishop Belo's prize but accused Ramos-Horta of causing problems. But the Nobel Committee said Ramos-Horta was not even in East Timor during the civil conflict. They said he tried to bring peace.

Meanwhile, diplomats from Indonesia and Portugal continued to meet. They tried to solve the problem of East Timor.

End of Indonesian Control

New talks between Indonesia and Portugal, helped by the United Nations, began in early 1997.

Changes in Indonesia

East Timor's independence was not allowed under Suharto's rule. Many feared an independent East Timor would cause problems for Indonesia's unity. However, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis caused huge problems in Indonesia. This led to Suharto's resignation in May 1998. He had been president for 30 years. Military operations in East Timor were costing Indonesia a million dollars a day.

The time after Suharto was more open politically. There was a big debate about Indonesia's relationship with East Timor. In Dili, people discussed a possible vote. On 8 June 1998, Suharto's replacement, B. J. Habibie, announced that Indonesia would offer East Timor a special plan for self-rule.

In late 1998, the Australian government suggested a vote on independence within ten years. President Habibie saw this as Indonesia still being a "colonial ruler." So, he decided to call a quick vote on the issue.

Indonesia and Portugal announced on 5 May 1999 that East Timorese people could choose. They could choose between self-rule or full independence. The vote would be managed by the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET). It was set for 30 August. Indonesia also said it would handle security. This worried many in East Timor.

The 1999 Vote

As groups for and against independence campaigned, some groups working with the Indonesian military started threatening violence. They were seen working with and getting training from Indonesian soldiers. Before the vote, an attack in Liquiça in April killed many East Timorese. In June, another group attacked a UN office.

Indonesian officials said they could not stop the violence. But Ramos-Horta and others did not believe this. He said Indonesia wanted to cause chaos before leaving.

As the vote got closer, reports of violence against independence supporters grew.

The day of the vote, 30 August 1999, was mostly calm. 98.6% of registered voters cast ballots. On 4 September, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan announced the results. 78.5% of votes were for independence. Many Indonesians were shocked. They had been told that East Timorese supported joining Indonesia.

Within hours of the results, groups working with the military started attacking people and setting fires in Dili. Foreign journalists and observers left. Tens of thousands of East Timorese fled to the mountains. Groups attacked Dili's Catholic church building, killing many. The next day, the Red Cross office was attacked and burned. Many people were killed in Suai. Reports of similar killings came from all over East Timor. The UN pulled out most of its staff.

When a UN group arrived in Jakarta on 8 September, Indonesian President Habibie said reports of violence were "fantasies" and "lies." General Wiranto of the Indonesian military said his soldiers had things under control.

Indonesia Leaves and Peacekeepers Arrive

The violence caused widespread anger in Australia, Portugal, and other countries. People pressured their governments to act. Australian Prime Minister John Howard spoke with UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and US President Bill Clinton. He asked for an Australian-led international peacekeeping force to enter East Timor. The United States provided important support. Finally, on 11 September, Clinton announced that future financial help for Indonesia would depend on how they handled the situation.

Indonesia, facing big economic problems, gave in. President BJ Habibie announced on 12 September that Indonesia would pull out its soldiers. He would allow an Australian-led international peacekeeping force to enter East Timor.

On 15 September 1999, the United Nations Security Council called for a multinational force. This force would bring peace and security to East Timor.

The International Force for East Timor, or INTERFET, led by Australian Major General Peter Cosgrove, entered Dili on 20 September. By 31 October, the last Indonesian troops had left East Timor. The arrival of thousands of international troops caused the groups working with the military to flee into Indonesia.

The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) was set up in October. It managed the region for two years. Control of the nation was then given to the government of East Timor. Independence was declared on 20 May 2002. On 27 September of the same year, East Timor joined the United Nations.

Most of INTERFET's forces were Australian. At its peak, there were over 5,500 Australian troops. In total, 22 nations contributed to the force, which had over 11,000 troops. The United States provided key support.

Aftermath

Number of Deaths

It is hard to know the exact number of people who died. A 2005 report from the UN's Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR) estimated that at least 102,800 people died because of the conflict.

Indonesian Governors of East Timor

- President of the Provisional Government:

- 17 December 1975 – 17 July 1976: Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo

- Governors:

- 1976 – 1978: Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo

- 1978 – 1982: Guilherme Maria Gonçalves

- 18 September 1982 – 18 September 1992: Mário Viegas Carrascalão

- 18 September 1992 – 25 October 1999: José Abílio Osório Soares

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |