Dili facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dili

Díli

|

|

|---|---|

|

Government Palace

Immaculate Conception Cathedral

National Parliament

Old Chinese Commercial Association building

Cristo Rei of Dili

Casa Europa

Dili Convention Centre

|

|

| Country | |

| Municipality | Dili |

| Capital of Portuguese Timor | 1769 |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 178.62 km2 (68.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 11 m (36 ft) |

| Population

(2023)

|

|

| • Capital city | 277,488 |

| • Density | 1,553.51/km2 (4,023.57/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 324,296 |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (TLT) |

Dili (in Portuguese and Tetum: Díli) is the capital and largest city of Timor-Leste. It is located on the northern coast of the island of Timor. The city sits on a flat area surrounded by mountains. Dili has a tropical climate with clear wet and dry seasons.

Since 1769, Dili has been the main economic center and port for what is now Timor-Leste. It was the capital of Portuguese Timor back then. Today, it is also the capital of the Dili Municipality. This area includes both the city and some nearby rural places. Dili's population is growing and is quite young, with many people of working age. The main local language is Tetum. However, many people from other parts of the country also live here.

The first settlement was in the eastern part of the city. Portuguese rule lasted for centuries, but it was interrupted during World War II. Dili became a battleground between Allied and Japanese forces. After the war, the damaged city returned to Portuguese control. In 1975, a civil war broke out between Timorese groups. This led to a declaration of independence, followed by an invasion by Indonesia.

During Indonesian rule, Dili's buildings and roads were improved. Important landmarks like the Immaculate Conception Cathedral and Cristo Rei of Dili were built then. The city grew, and its population reached over 100,000 people.

People who resisted Indonesian rule faced harsh treatment. A massacre in Dili led to international pressure. This pressure resulted in an independence vote. After the vote for independence, violence erupted in the city. Much of Dili's buildings were destroyed, and many people had to leave. The United Nations then took over, helping to rebuild the city. Dili became the capital of independent Timor-Leste in 2002.

In 2006, another period of violence caused more damage and forced people to move. In 2009, the government started the City of Peace campaign to reduce problems. As the population keeps growing, the city has expanded along the coast to the east and west.

Dili's infrastructure is still being improved. It was the first place in Timor-Leste to have 24-hour electricity. However, its water system is still developing. Education levels are higher here than in other parts of the country. The nation's universities are also in Dili. An international port and airport are within the city. Most jobs are in the service industry and public services. The government is also working to boost tourism by highlighting Dili's culture, nature, and history.

Contents

Dili's History

Early Portuguese Settlement

Dili has always been important in Timor-Leste's history. Records from before the 1700s are not very detailed. Many historical documents were lost because of conflicts in 1779, 1890, 1975, and 1999.

Timor island was known for sandalwood in the 1400s. The first Portuguese trip to the island for sandalwood was in 1516. By 1524, regular trade was happening. In the late 1500s, Portuguese officials started overseeing Timor.

The Netherlands began competing for control of the island in 1613. A rebellion in 1629 forced the Portuguese away for three years. In 1641, some Timorese kings became Catholic, seeking Portuguese protection. This made Portuguese influence more political, not just economic. Timor became separate from Solor in 1646. It got its first dedicated governor in 1702, who lived in Lifau.

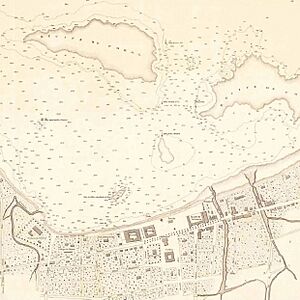

In 1769, the Portuguese governor, António José Teles de Meneses, moved the capital. He moved it from Lifau to Dili because Lifau was becoming too influenced by local families. Dili was part of the Motael kingdom, whose leader was friendly with the Portuguese. The governor used an existing fort and built a new settlement. The area was good for rice farming. A wall was built to separate the city from wetlands to the south. The first settlement had three groups: Portuguese, mixed-race people, and soldiers from another kingdom.

From 1788 to 1790, a civil war happened between the governor in Dili and an official in Manatuto. A new governor resolved this. A permanent military force was created in 1818 to respond to Dutch actions. Some Europeans settled in Lahane to the south.

Major construction happened under Governor José Maria Marques in 1834. He rebuilt the city in a grid pattern. The city expanded along the coast and southwards as wetlands were drained. A road was built to Lahane and Dare. The city center was around the port. It had trade buildings, churches, military and government offices. Only the church and one house were made of stone. East of the center was Bidau and a Chinese settlement. West was the Motael kingdom's main area.

In 1844, Timor became a new Portuguese province. When explorer Alfred Russel Wallace visited in the 1860s, he described the governor's house as a "low whitewashed cottage." Most other buildings were mud and thatch. Swamps surrounded the town. More permanent buildings were built in the late 1800s. A new church was built in 1877.

A revolt in the east isolated the city in 1861, but it was defeated. In 1863, Dili was declared a city. East Timor became directly under Lisbon's government. In 1887, a mutiny in Dili led to the governor's death. The territory became a full province in 1909. Another revolt happened after Portugal's 1910 revolution. A civil government was set up in 1913.

Portuguese-style buildings continued to be built into the 1900s. A new town hall was built from 1912 to 1915. The main church was replaced by a new cathedral in 1937. Four residential areas grew around the city center: Bidau, Benamauc, Caicole, and Colmera. Motael became home to the city's lighthouse. Motael Church began construction in 1901. A Chinese cemetery and military area called Taibesse were inland. Lahane also grew. Dili became part of the Dili municipality in 1940.

Destruction, Rebuilding, and Indonesian Rule

During World War II, Portugal and its colonies stayed neutral. However, the Allies saw East Timor as a target for Japan. Australian and Dutch troops were sent to Dili in 1941. In response, the Japanese invaded Dili as part of the Battle of Timor. The city was mostly empty before the invasion. Allied forces retreated into the island. The Japanese left the Portuguese governor in charge but took over administration. Much of Dili was destroyed during the war by the Japanese invasion and later Allied bombings. Japanese forces on Timor surrendered to Australian forces. An Australian official informed the Portuguese governor of the Japanese surrender on September 23, 1945.

After World War II, Dili covered what is now the old city core. An urban plan was developed in 1951 for city layout, roads, and building rules. This plan aimed for separate neighborhoods for different groups. It also expected more people to move from rural areas to the city. The plan was not fully completed, and the city remained underdeveloped.

A 1950 census found Dili's population was about 6,000 people. By 1960, it was about 7,000. By 1970, the urban population reached around 17,000. The city did not extend far beyond the port area. Its population did not exceed 30,000 before 1975.

Portuguese Timor became a full part of Portugal in 1951. However, locals gained little political power. The Portuguese Overseas Organic Law of 1963 created the first Legislative Council. It also theoretically gave voting rights to more people.

Portugal's 1974 Carnation Revolution brought changes to East Timor. New political parties formed, aiming for independence. These parties often disagreed. Some, like the Timorese Democratic Union (UDT), wanted to join Indonesia. On August 11, 1975, the UDT started a coup. Their control was limited outside Dili. On August 20, the opposing Fretilin party tried to take the city. After some days, Fretilin took control. The last Portuguese governor fled Dili on August 26.

On November 28, Fretilin declared independence in Dili. On December 7, Indonesia landed troops in the city. This was part of an invasion of East Timor. Many people fled Dili. This invasion brought the territory under Indonesian rule. On July 17, 1976, Indonesia made East Timor its 27th province.

Indonesia continued to govern from Dili. The city's population kept growing, reaching 80,000 in 1985 and over 100,000 in 1999. This was partly due to people fleeing conflict in rural areas. Indonesia improved the city's buildings and roads. They built the Immaculate Conception Cathedral, the Integration Statue, and the Cristo Rei of Dili. However, many in Dili still supported the resistance. By the 1990s, the city had spread out, using most of the flat land.

In the 1980s, resistance grew among young people in Dili. In 1989, a visit by Pope John Paul II was interrupted by independence activists. On November 12, 1991, Indonesian forces were filmed shooting at a funeral procession. This event, known as the Santa Cruz massacre, led to global criticism of Indonesia. It increased pressure for East Timorese self-determination.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis and a drought caused food shortages in Dili. This crisis also led to the resignation of Indonesian President Suharto. His successor, B. J. Habibie, approved a vote on East Timorese independence. Violence from pro-Indonesian groups happened before the vote. In August 1999, East Timor voted for independence.

The vote led to extreme violence. Pro-Indonesian groups caused much damage. On September 4, when the result was announced, Indonesian police began to leave Dili. International media reported 145 deaths in the first 48 hours. Most foreigners were evacuated. Violence continued, destroying many buildings and homes. 120,000 people became refugees. International pressure led to a peacekeeping force. The Australian-led International Force East Timor arrived on September 20.

Growth Under UN Rule and Independence

Dili continued to grow under UN rule. The UN government did not invest in infrastructure outside Dili as much as Indonesia had. This led to more people moving to Dili. Abandoned houses were taken over by people who had nowhere else to live. Most new people came from eastern areas of the country. This growth, combined with a weak economy, led to more urban poverty and unemployment, especially among young people.

By 2004, Dili's population reached 173,541. Unemployment was 26.9% overall. For men aged 15–29, it was 43.4%. About half of these young men worked in unofficial jobs. In 2005, a new urban plan was developed. Food shortages happened often in the early years of independence. From 1990 to 2014, farming land around Dili decreased by about 40%. It was replaced by gardening, fish farming, and urban areas. Wetlands also decreased as they were drained and built upon.

By 2006, Dili produced half of the country's non-oil economy. It also received two-thirds of government spending. However, economic benefits were not shared equally. After 1999, Indonesian food subsidies ended, and buildings were destroyed. This caused prices to rise quickly. Under UN rule, the use of the US dollar and international organizations' spending also increased prices. By 2006, Dili had the eighth-highest living costs in Asia, even though the country had Asia's lowest GDP.

In April 2006, disagreements within the military led to street violence in Dili. Disputes over housing also caused property destruction. Most of the 150,000 people displaced were from Dili. About half of the city's residents were affected. Around 72,000 people went to camps, and 80,000 fled to rural areas. Rice prices in the city increased greatly. Foreign military help was needed to restore order.

A National Recovery Strategy was put in place after the 2007 national election. This plan aimed to help people return. By 2008, about 30,000 displaced people from Dili were still in camps. By 2009, most had returned, and the camps closed. However, some community tensions remained. Continuing unrest led to attempted assassinations of the president and prime minister.

In May 2009, the Dili City of Peace campaign was launched by Jose Ramos-Horta. This effort aimed to build unity and prevent violence. It included discussions, a cycling tour, a marathon, and tree planting. The campaign focused on Dili because of its influence on the whole country. The Latelek (Bridge) Project from 2010 to 2012 helped improve community ties. Other programs helped with skills, youth, and women's empowerment. Some local communities created rules to reduce violence.

The city's growth since independence has changed many places. In 2009, the area around the Indonesian-built Integration Monument became the 5 May Park. A 1960s hotel, Hotel Turismo, was rebuilt in 2010. The former police headquarters was replaced by the Indonesian embassy's cultural center. By 2010, the municipal population reached 234,026. In 2018, it reached 281,000. In April 2021, during COVID-19 restrictions, the city had its worst flood in 50 years.

Geography of Dili

Land use within Dili's urban area as of 2014 Residential (49.0%) Commercial (5.3%) Industry (1.9%) Public (6.2%) Military (0.5%) Infrastructure (2.6%) Religious (1.0%) Roads (8.1%) Agriculture (7.2%) Open (10.2%) Water (8.0%)

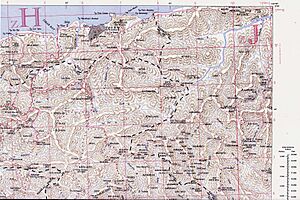

Dili is on the northern coast of Timor island. This island is part of the eastern Lesser Sunda Islands. It is in the UTC+9 timezone. The Ombai Strait of the Savu Sea is offshore. To the south are the central mountains of Timor. These mountains extend north to the coast on the west and east sides of the city. The ground is mostly limestone and marine clay.

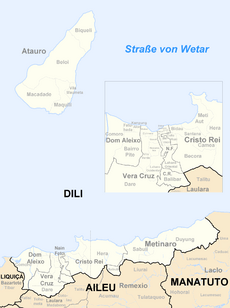

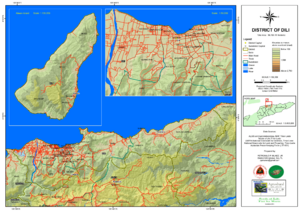

Dili's exact location is around 8°35′S, 125°36′E. The city is mostly within the larger Dili Municipality. This municipality used to include Atauro Island, but Atauro became a separate municipality on January 1, 2022. Dili is bordered by Aileu, Liquiçá, and Manatuto. The municipality has 31 sucos (local areas), divided into 241 aldeias (villages).

The urban area of Dili city covers four of the Dili Municipality's Administrative Posts: Cristo Rei, Dom Aleixo, Nain Feto, and Vera Cruz. 18 sucos within these are considered urban. This urban area is about 48 square kilometers. The wider urban area extends west into the Tibar suco of the Bazartete Administrative Post in the Liquiçá Municipality. The total area of all sucos in the urban region is 17,862 hectares. However, much of this land is too steep for building. As of 2014, only 25.5% of the total area was developed.

The main city is in flat lowlands, mostly between 0 and 60 meters high. The slope is usually under 15 degrees. This area includes a alluvial plain, and many beaches line the coast. The soil is quaternary alluvium. The distance between the sea and the mountains is only about 4 kilometers at its widest. The surrounding mountains near the city have slopes of 20 degrees or more. On both sides of the city center, mountain ridges extend to the coast. This causes urban development to spread onto flat land beyond these ridges. Tibar is on the other side of the western ridge, and Hera is on the other side of the eastern ridge.

The Comoro River flows through the western side of the city. The Bemorl and Benmauc Rivers join in the East. The Maloa river is between them. The Maucau river flows through Tibar, and the Akanunu and Mota Kiik rivers flow through Hera. The Comoro is the largest river. Water levels in these rivers change a lot between the dry and wet seasons. Parts of the city face drought and flood risks from rivers. These issues are linked to climate change. Small floods happen in some houses a few times a year. Reports of land subsidence (sinking) are found throughout the city. The Maloa river floods most often. Landslides have caused damage and deaths before. The area also faces earthquake and tsunami risks, but no major events have occurred. Air pollution is a growing problem, caused by forest fires, wood cooking, and vehicles.

Dili's Ecology

The land around Dili naturally has dry deciduous forests. Common trees include Sterculia foetida, Calophyllum teysmanii, and Aleurites moluccana. Eucalyptus alba is found in rocky areas. Palm and acacia trees are also present. Eucalyptus trees are often used for firewood. Nuts from A. moluccana are sometimes burned for light. Trees in urban areas include Alstonia scholaris, Albizia julibrissin, Ficus microcarpa, and various fruit trees. Forests around the city have been damaged by logging for building and firewood. The government aims to replant these areas. Large wildlife in these forests includes monkeys.

Mangrove species along the coast include the near-threatened Ceriops decandra. Coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and intertidal mudflats are also present. The coral reefs off Dili seem protected from rising sea temperatures. However, human activities cause some damage. Seagrass beds support dugongs and sea turtles. Dolphins and whales are found offshore.

There are three protected nature areas in Dili: Behau, Cristo Rei Protected Area, and Tasitolu. The Cristo Rei Protected Area is 18.1 kilometers long. It is on the mountains between central Dili and Hera. The Tasitolu area is 3.8 kilometers long. It is near the border of the Dili and Liquiçá municipalities. It covers land and some coastal waters. It is being developed as a recreation and holy site. The large Behau protected area is 274.9 kilometers long. It covers much of the sea off eastern Dili and coastal areas in Hera. Behau is the newest proposed area. The government is thinking about replacing it with smaller areas. BirdLife International has identified Cristo Rei Protected Area and Tasitolu as Important Bird Areas. Near-threatened bird species found here include the black cuckoo-dove, the pink-headed imperial pigeon, and the Timor sparrow.

Dili's Climate

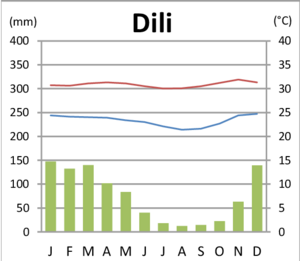

Dili has a rather dry tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw). A rainy season lasts from November to April. A dry season lasts from May to October. Rainfall is highest in December, averaging 170 mm between 2005 and 2013. It is lowest in August, averaging 5.3 mm over the same period. The overall average is 902 mm annually, but rainfall varies a lot each year.

Average temperatures are around 26 to 28 °C. This changes by 10.8 to 13.8 °C throughout the day. Minimums are around 20 °C, and maximums are over 33 °C. Temperature changes are larger during the dry season. Climate change is shifting weather patterns. It may make extreme weather events worse. The highest recorded temperature in the city up to 2013 was 36 °C in November 2011. The lowest was 14 °C in August 2013.

| Climate data for Dili (1914–1963) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.0 (96.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

34.1 (93.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.3 (88.3) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.9 (87.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.1 (75.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 139.5 (5.49) |

138.7 (5.46) |

132.7 (5.22) |

104.3 (4.11) |

74.9 (2.95) |

58.4 (2.30) |

20.1 (0.79) |

12.1 (0.48) |

9.0 (0.35) |

12.8 (0.50) |

61.4 (2.42) |

144.9 (5.70) |

908.8 (35.77) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 80 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 82 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 72 | 71 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 77 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 189.1 | 161.0 | 235.6 | 234.0 | 266.6 | 246.0 | 272.8 | 291.4 | 288.0 | 297.6 | 270.0 | 220.1 | 2,972.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.1 | 5.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 8.1 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst | |||||||||||||

Buildings and Monuments in Dili

The old part of Dili is in the city's eastern half. The original Portuguese settlement was built in a grid pattern along the shore. The city has grown along this east-west line. The older areas are the most crowded, with little empty land. The western part of the city has the airport and the newest urban growth. Most buildings were destroyed in 1999, including 68,000 homes. After rebuilding, 71.6% of houses had concrete or brick walls by 2010. In Hera, however, just over 50% of houses were mostly wooden in 2014.

Land rights are still complex due to the 2006 crisis. It is hard to know who officially owns land. This is because land records were taken to Indonesia in 1999. The government tried to charge a small rent for state property. But many people could not pay. In 2003, the government said all former state and abandoned properties belonged to the state. It also set up a system for people to claim land based on who was living there. The 2006 crisis stopped efforts to collect rent. Evictions from state property are rare. A land survey started in 2008. By 2014, 70% of Dili's land was surveyed, but this information is not public. Despite this, most people in the city claim ownership of their homes. 90% of homes are considered owned by an individual or family. Land value is often unclear.

Important government buildings are near the Port of Dili. The city's edges are the newest areas and grew without much planning. The central core (Bairro Central) has most government buildings. It has many buildings made of stone. This area still has many buildings with Portuguese-era architecture. East of the central government area is the old Chinese area. It still has Chinese-influenced buildings.

Portuguese-era buildings are most common in the Motael, Gricenfor, and Bidau Lecidere sucos. They are often along the main road, Avenida Nicolau Lobato. The main government complex is at Largo Infante Dom Henrique, by the sea. The main building here is the Government Palace. It has three two-story buildings connected by an archway. They were built between 1953 and 1969. Another old building is the former Market Hall.

The government has identified many heritage buildings, especially in the old quarter. New buildings are being built for cultural institutions. The Museum and Cultural Centre of Timor-Leste will hold the country's cultural items. The National Library of Timor-Leste will be both a library and a national archive.

Notable churches include the Motael Church, the oldest in the country. It became linked with resistance to Indonesian rule. The Immaculate Conception Cathedral was built to be the largest church in Southeast Asia. The Cristo Rei of Dili is a 27-meter tall statue of Jesus. It is on top of a globe at the end of the eastern Fatucama peninsula. It is at the end of a Stations of the Cross path with over 500 steps. It was a gift from Indonesia during its occupation. Its height shows that East Timor was Indonesia's 27th province when it was built in 1996.

The Integration Monument celebrates Indonesia's annexation in 1976. It is a statue of an East Timorese warrior breaking chains. It was meant to link Timorese identity with Indonesian rule. The monument has not been removed. It is now seen as representing the fight against both periods of foreign rule.

The National Stadium has two seating stands. It can hold about 9,000 people. It is often used for association football, the country's most popular sport. Sometimes, the national team plays home games in other countries due to stadium issues. In the past, it has been used to house refugees and give out aid.

-

Pura Girinatha Hindu temple, built during Indonesian occupation

City Administration

Dili is the main administrative center for the Dili Municipality. It serves as both the municipal and national capital. Dili itself does not have a city government. It is managed by the Dili Municipality, which also includes the Hera and Metinaro areas. The current president of the Dili Municipality Authority is Gregório da Cunha Saldanha, who started his role on March 1, 2024. The municipality has an elected mayor and council.

Timor-Leste's municipalities are divided into administrative posts. Each post is divided into sucos. The central city of Dili is spread across four of the six administrative posts in Dili municipality: Cristo Rei, Dom Aleixo, Nain Feto, and Vera Cruz. The Hera suco is the easternmost suco of Cristo Rei. Tibar, west of the main city, is the easternmost suco of the Bazartete Administrative Post in the Liquiçá Municipality.

Each suco has a chefe (chief). Dili's chiefs have less power over community land than those elsewhere. However, their elected status gives them more authority in other areas. Each suco also has a main office. Municipal and national government buildings are in the city center. Sucos, administrative posts, and municipalities all set up Disaster Management Committees. These committees plan, raise public awareness, and respond to disasters. The borders of sucos and their aldeias are often unclear. This is due to past displacements and cultural reasons.

Land registration is difficult because of the city's troubled history. Legal ownership is often not clear. It is believed that existing land records were taken from Dili to Indonesia in 1999. The new government tried to set up a rent system. They charged a small fee of $10 a month for people living on state property. But many could not pay this. In 2003, the national government passed a law stating that all former state property and abandoned properties belonged to the state. It also created a system for people to register land based on who was living there. Residents can claim land if no one else objects. The 2006 crisis ended attempts to enforce rent. Evictions from state property are rare. A land survey began in 2008. As of 2014, 70% of Dili's land had been surveyed, but this information is not public. Despite this lack of information, most people in the city claim ownership of their homes. 90% of homes are considered owned by an individual or family. Land value is often unclear.

The sucos within the four administrative posts in the western Dili Municipality that form the core city are:

Cristo Rei

- Balibar

- Becora

- Bidau Santana

- Camea

- Culuhun

- Hera

- Metiaut

Dom Aleixo

- Bairro Pite

- Comoro

- Fatuhada

- Kampung Alor

Nain Feto

- Acadiruhun

- Bemori

- Bidau Lecidere

- Gricenfor

- Lahane Oriental

- Santa Cruz

Vera Cruz

- Caicoli

- Colmera

- Dare

- Lahane Ocidental

- Mascarenhas

- Motael

- Vila Verde

Dili's Economy

Dili's economy is much better than the rest of the country's. Most of the wealth is in Dili. Almost all of Dili's sucos have the highest living standards and best access to public services. The Dili district has a much higher living standard than any other part of the country. While poverty rates in the municipality range from 8% to 80%, every suco within the city itself has high living standards. 57.8% of people in the capital are relatively wealthy, compared to 8.7% in rural areas.

In 2010, the service industry employed 44% of workers. Government jobs provided about 25% of jobs. The farming sector is slightly smaller than government jobs. The manufacturing sector remains small. The working-age population grew by almost 50% from 2004 to 2010. Unemployment dropped from 26.9% to 17.4%. However, youth unemployment in the municipality was 58% in 2007, higher than the national average of 43%. Dili attracts younger, educated people from other parts of the country.

The city is part of the government's "Northern Regional Development Corridor." This area stretches along the coast from the Indonesian border to Baucau. Within this, Dili is part of the "Dili-Tibar-Hera" area. Here, the government plans to develop the service sector. The city is also part of the central tourism zone. Historical sites and eco-tourism are promoted. Whale watching is possible off the coast. There are many scuba diving sites near the city. Some tourism and industrial areas are being developed in the metropolitan area. There is a large informal economy that includes some officially unemployed residents.

Tourism numbers increased from 14,000 in 2006 to 51,000 in 2013. Half of visitors arriving at Dili's airport come from Australia, Indonesia, and Portugal. By 2012, there were at least 14 hotels in the city. Most hotels are run by local companies. Few international chains are present. Nightly rates are high for the region. This is partly because there are not enough tourists to benefit from larger-scale operations. Important hotels include Hotel Timor and Hotel Dili.

Most large investments come from the public sector. However, a small private sector is growing. The Dili municipality produces about 40% of the country's fish. Most of this fish is eaten locally. The country's three main commercial banks operate mostly in Dili.

The Port of Dili is the country's largest. It handles most international shipping. There are regular ships to Darwin (Australia), Kota Kinabalu (Malaysia), Surabaya (Indonesia), and Singapore. Less frequent shipping goes to other Indonesian ports. As of 2011, the port processed 200,000 tons of goods annually. This had increased by 20% each year for the previous six years. 80% of the goods processed are imports.

Dili's People

The 2022 census found Dili Municipality's population was 324,269. Of these, 82.4% lived in urban areas. The municipality had the largest population and the highest growth rate since 2015. However, average household size decreased from 6.4 to 5.7 people. The city has almost twice as many homes as all other urban areas in the country combined. The municipality is the most densely populated in the country, with 1,425 people per square kilometer. This is eight times denser than the second most crowded municipality. Dom Aleixo, with 166,000 people, remained the country's most populated administrative post. By 2030, the municipality's population is expected to reach around 580,000.

The gender ratio in 2022 was about 103 men for every 100 women. This is similar to the national average. The dependency ratio (number of dependents per working-age person) is 51 dependents for every 100 working people. This is much lower than elsewhere in the country. It is likely due to young adults moving into the city. Every other municipality in the country has more people leaving than arriving. Dili gains 36.9% of its population from people moving in. The literacy rate for those 10 and older was 89.6%. Only 5.4% of homes had piped water, a toilet, a bath or shower, and a kitchen.

Due to limited space, a small number of people settled in hilly and mountainous areas starting around 1990. This was especially true in southern areas near the national highway. However, many properties were left empty after the independence vote. So, much of the settlement in the 21st century has been into these empty areas. Population density tends to be higher in unplanned settlements than in planned neighborhoods.

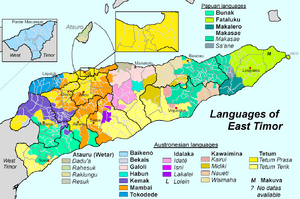

The main local language is Tetum. It was promoted during Portuguese rule and is now an official language. Speakers of other languages of Timor-Leste are in the city. The official language of Portuguese and the working languages of English and Indonesian are also spoken. A Malay-based creole called Dili Malay is spoken by about 1,000 residents. They have family links to Alor Island. People moving into the city often settle near others from similar backgrounds.

Education in Dili

Education is more common in Dili Municipality than in other parts of the country. The attendance rate at primary schools increased from 37% in 2004 to 73% in 2010. As of 2010, 86% of those five or older in the municipality had attended primary school. This is similar to the literacy rate. Within the metropolitan area, education rates are highest in Nain Feto and Vera Cruz, where 88% have attended primary school. Dom Alexio follows at 87%, and Cristo Rei at 81%. Tibar, outside Dili Municipality, has the lowest at 75%.

As of 2013, there were 108 schools in Dili, Hera, and Tibar. These included primary, secondary, and specialist schools. Of these, 61 were public and 47 private. This meant 4.8 schools per 10,000 people. In 2011, 43% of students in the Dili municipality studied in private schools. Many private schools are run by the Catholic Church, like the Don Bosco Training Center. They run 32% of all schools in the Dili Municipality.

Seventy-six percent of the country's university students study in the municipality. This is why some people move to the city. The National University of Timor-Leste created a "University City" plan to develop the Hera area.

City Infrastructure

Up to 70% of the country's infrastructure was destroyed in 1999. This included almost the entire electrical grid and much of the water system. Dili's airport and port were repaired in the six years after this. Electricity and telecommunications were also fixed. The city's fast population growth has put a strain on some of its services. Laws from before independence that ban building within 100 meters of water bodies are not enforced. Population growth has led to houses being built in flood-prone areas, including along dry river beds and canals.

Utilities in Dili

Electricity

In the early years of UN rule, electricity came from the Comoro power station. It had a 16 MW diesel generator. By 2004, there were 23,000 connections in the city. Dili was the only place in Timor-Leste with 24-hour electricity. Electricity demand was highest from 7 PM to 10 PM. By 2009, Comoro was producing 32 MW. By 2010, 92.3% of Dili's homes used electricity for lighting. However, 66.2% of households still cooked using firewood. Only 10.1% used electricity for cooking. Not paying electricity bills has caused some funding problems. In 2011, only 40% of businesses paid their electricity bills.

In November 2011, new diesel generators at the Hera Power Station started working. They produced 119 MW. This replaced the Comoro station's operations. Hera could produce electricity using 17% less fuel. A new substation was built to supply Dili. Transmission lines connect Dili to other cities along the northern coast. As of 2016, Dili's peak power demand reached 42.11 MW. The development of electricity infrastructure since independence has greatly reduced electricity costs. It went from 249 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2002 to 5 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2014.

Telecommunications

Most phone use in the country is with mobile phones. Most of the country's 3,000 landlines are in Dili. They are mainly used by the government and businesses. There are no submarine communications cables connecting to the country. So, internet access comes from satellites. This is expensive. National internet use was just over 1% in 2016. The government has approved the installation of the Timor-Leste South submarine Cable (TLSSC). It will connect to Darwin in Australia. Another cable will connect to the Indonesian island of Alor. As of 2020, there were three telecommunications companies in the country: Telemor, Telkomcel, and Timor Telecom.

Water and Sanitation

Access to clean water and sanitation is a problem for some homes. Over $250 million was invested by the UN and other groups to build Dili's water system. Existing water sources and pipes are enough for the city's immediate needs. But work continues to improve quality and reliability. In 2007, 25% of residents had 24 hours of water. As of 2013, 36% of homes were connected to the water system. Half of Dili received less than six hours of water a day. Water quality was also inconsistent, and boiling was advised. By 2015, less than 30% of people in Dili had continuous water. In 2018, water was available for 4 to 8 hours on average.

Water is managed by the National Directorate of Water and Sanitation Services (Dirasaun Nasional Sistema Agua no Saneamentu/DNSAS). They get 60% of water from groundwater. This started in the 1980s and sped up after independence. Private groups also pump water from the aquifer without rules. Despite inconsistent supply, 91% of people in urban areas have some access to safe drinking water. Sources include pumps, public taps, and wells. Some homes have tanks to help when water service stops. Half of the city's water comes from a local aquifer. There are four water treatment plants at the city's southern edge. Water tariffs (fees) were put in place in 2004 but removed in 2006 after the 2006 East Timorese crisis. By 2010, 27,821 cubic meters of water were pumped from the aquifer daily. This was almost as fast as the aquifer could refill. Trials for reintroducing water fees began in 2013. Increased use means the Dili Groundwater Basin cannot meet demand during the dry season. More wells have increased demand. Development changing drainage patterns has limited how fast the aquifer can refill. Downstream areas also face saltwater getting into the water.

Dili has the country's water testing laboratory. So, its water quality is regularly checked. The lack of factories in the city is thought to limit water pollution. However, pollution risks come from untreated household water discharge. Leaks from latrine pits into the soil and high water table also cause problems. Water stored in homes and some wells has been found to have bacteria. As of 2010, only 16% of homes emptied their latrine pits. Hera and Tibar do not have water treatment plants. Residents there rely on wells and water trucks. As of 2010, daily water demand was 32,000 cubic meters in Dili proper.

Drainage systems are not enough for the wet season. Drains are often blocked, causing common flooding. This damages property and creates health concerns. Thirty-six water channels are in the city besides its rivers. These often collect rainwater. However, growing urbanization reduces how much water can soak into the ground. This worsens flood risks. There is no city-wide sewer system. As of 2010, only 30.3% of homes had a septic tank. The most common sewage system was pit latrines, used by 50.7% of homes. Among homes with toilets, 97% were flushed by manually pouring water. Wastewater is often collected by trucks from some areas. Some wastewater is treated in ponds in Tasitolu. Dili also has one of the country's two septage treatment facilities. A Sanitation and Drainage Masterplan was created for the city in 2012. It planned for eight wastewater treatment systems by 2025.

As of 2014, Dili produces 108 tons of solid waste per day. Over half of this waste is biodegradable. The government-funded waste collection system covers Cristo Rei, Dom Aleixo, Nain Feto, and Vera Cruz. Waste is collected by government trucks and private trucks hired by the government. Collected waste goes to a landfill in Tibar. This landfill was set up during the Indonesian period. Metal collected by waste pickers is sold to Malaysia and Singapore for recycling. Some biodegradable waste is composted by a private company. Some waste is burned. Waste collection schedules vary. Some areas get daily collection, while some get none. Collection is less frequent in Hera and Tibar than in Dili proper.

There are 14 hospitals around the Dili metropolitan area. Nine are in Dom Aleixo, three in Vera Cruz, one in Cristo Rei (in Hera), and one in Tibar. Dom Aleixo also has two health centers. Cristo Rei has one health center in Dili proper, and Nain Feto also has a health center. The National Hospital of Timor-Leste is in Dili. It provides primary and secondary health care. A specialist hospital is planned to be built by 2030. It will treat diseases like cancer that are currently treated outside the country.

Transportation in Dili

Land Transport

As of 2015, Dili Municipality had 1,475 kilometers of roads. Half of these were classified as National, District, or Urban roads. Roads going into and out of Dili to the East and West carry over 1,000 non-motorbike vehicles daily. Besides the Eastern and Western national roads, a third national road goes south from the city. Within Dili, traffic is increasing. Poor road quality is the most common cause of accidents and delays. Many roads are unpaved. In the old quarter, streets are often one-way. The only four-lane roads in the city are National Road A01 and Banana Road. As of 2016, there were four roundabouts and 11 intersections with traffic lights. Few routes travel along the east-west line. For most of the time since independence, there was only one vehicular crossing over the Comoro river. This bridge was expanded from two lanes to four lanes in June 2013. The two-lane Hinode Bridge opened upriver in September 2018. It connects Banana road to National Road No 03. This bridge is also expected to be expanded to four lanes in the future.

The usual public transport in the city is the minibus. These are run by private companies that buy route permits from the government. Each vehicle usually holds ten people. There are no official schedules and few official bus stops. Fares are cheap, at $0.25. Dili also has a fleet of air-conditioned blue taxis. Their drivers are expected to speak Tetum and English.

Street names are in Portuguese, as are many official signs. Tetum is used for more informational signs. English and Indonesian are rare on official signs but common elsewhere. Chinese is used on some unofficial signs. Even under Indonesian rule, when Portuguese was banned, Portuguese street names remained.

Sea Transport

The Port of Dili has a total berth length of 289.2 meters. Depths alongside the berth range from 5.5 meters to 7.5 meters. This port was the only international cargo port in the country. But its capacity was not enough for import needs. The Tibar Bay Port was planned to handle all cargo shipping. This would leave the current Dili port to become a ferry terminal. Tibar Bay Port was expected to be built starting in 2015 and open in 2020. On June 3, 2016, the government signed a Public-private partnership agreement with Bolloré. This gave the company a 30-year lease on the new port. A construction contract was given to the China Harbour Engineering Company in December 2017. Construction began on August 30, 2019. It was scheduled to finish in August 2021. As of December 2020, construction was 42% complete. Delays happened because Chinese workers returned to China during the COVID-19 pandemic. The port was then expected to open in April 2022. The port received its first ships on September 30, 2022. It was officially opened on November 30, 2022.

A dry port has been created 8 kilometers from the main Port of Dili. There is also a naval port in Hera. Cargo operations in Dili Port stopped on October 1, 2022. A twice-weekly ferry service runs between Dili and Oecusse. A ferry travels between Dili and Atauro once a week. The Dili Port is the main link for these places with the rest of the country. These ferries drop off people and vehicles onto a slipway, not a dedicated berthing area.

Air Transport

The Presidente Nicolau Lobato International Airport is in the city. It is named after independence leader Nicolau Lobato. It has regular flights to Darwin (Australia), Denpasar (Indonesia), and Singapore. In 2014, it served 198,080 passengers and 172 tons of cargo. It has one runway, which is 1,850 meters long and 30 meters wide. It is 8 meters above sea level. A lack of runway lighting prevents night-time landings. So, the airport operates from 6 AM to 6 PM. The passenger terminals were originally domestic terminals during the Indonesian period. This means they are not well-designed for international customs and immigration. Due to the runway's size, only medium-sized planes like the A319 and B737 can land. There is also limited space for aircraft parking. The runway is limited by the sea and the Comoro river. However, there are plans to extend the runway by adding land or building a bridge over the river. A new international terminal is also planned. Despite this, the airport is thought to be able to handle demand until 2030.

This is the only working international airport in Timor-Leste. There are also airstrips in Baucau, Suai, and Oecusse used for domestic flights. Until recently, Dili's airport runway could not handle aircraft larger than the Boeing 737 or C-130 Hercules. But in January 2008, the Portuguese airline EuroAtlantic Airways flew a direct flight from Lisbon using a Boeing 757. It carried 140 members of the Guarda Nacional Republicana.

Culture in Dili

In Dili, cultural differences exist not only between different language groups but also between older residents and new immigrants. Newcomers often keep their cultural practices. Legal traditions from Portuguese and Indonesian rule do not always match local customs, like how marriages are recognized. People who move to Dili from rural areas keep their cultural ties to their home regions. These ties are passed down through families. City residents often go back to rural areas for traditional ceremonies, especially during the dry season and elections.

Local communities have important traditional houses. They also have sacred natural areas like specific trees, rocks, and wells. There are also many Uma Lulik (sacred houses). As in the rest of the country, village chiefs still have some influence in Dili's communities. However, suco populations in Dili are more diverse than in rural areas. So, suco chief power is not as strong. Community ties are more common at the aldeia (village) level. Or they are formed through religious or economic connections. New arrivals often settle near people from their same home area. This has made Dili's urban population a mix of different communities. Moving back and forth between Dili and rural areas is common. Also, while rural sucos are often culturally similar, Dili's administrative boundaries do not match its cultural settlement patterns.

Some aldeias are more culturally mixed and have people from different economic backgrounds. In diverse aldeias, smaller communities sometimes form with their own unofficial leaders. Some urban areas show separation based on jobs or social status. Core urban areas are mostly home to wealthier families. These are often families who were considered mixed-race or assimilated under Portuguese rule. Some aldeias mostly have people of foreign descent or temporary students.

Dili has many local groups, often for young people. While sometimes called gangs, many act more like social groups connected to their local community. These groups have a long history. Many formed to resist Indonesian rule. Some street art still shows themes of resistance. The members of these groups often reflect their rural origins. They also show the broader East-West divide in the country.

The national government has a culture policy. It includes providing cultural facilities in Dili. It aims for the city to show diverse cultural influences. Developing cultural facilities has included building libraries and museums. It also involves creating audio-visual multimedia centers to make information more accessible. The City of Peace campaign aims to keep the capital stable. It brings young people together for discussions and promotes national pride. Large events where locals work together are important parts of this campaign. One important event is the Dili City of Peace marathon. It was first held in June 2010 and became an annual event. It includes a full marathon, a half marathon, and a seven-kilometer "Run for Peace."

Dili had no cinema until 2011. Then, one opened in a new shopping center called Timor Plaza. The country's first local feature film, Beatriz's War, was released a couple of years later. In 2019, the city hosted the first Dili International Film Festival. It was held again in 2020. Radio is very popular, and the city has 13 FM radio stations.

International Relations

Diplomatic Missions

Embassies

Consulate Generals

Honorary Consulates

Twin Towns – Sister Cities

Dili is twinned with the following places:

Canberra, Australia (2004)

Canberra, Australia (2004) Coimbra, Portugal (2002)

Coimbra, Portugal (2002) Darwin, Australia (2003)

Darwin, Australia (2003) Lisbon, Portugal (2001)

Lisbon, Portugal (2001) Macau, China (2024)

Macau, China (2024) Manila, Philippines (2011)

Manila, Philippines (2011) Margao, India (2001)

Margao, India (2001) Okinawa, Japan (2005)

Okinawa, Japan (2005) Praia, Cape Verde (2001)

Praia, Cape Verde (2001)

See also

In Spanish: Dili para niños

In Spanish: Dili para niños

- List of people from Dili

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |