History of East Timor facts for kids

East Timor, officially called the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. It covers the eastern part of the island of Timor and the nearby islands of Atauro and Jaco. The first people to live here were likely descendants of Australoid and Melanesian groups. Portuguese traders arrived in the early 1500s and later colonised the area. After some fights with the Dutch, Portugal gave up the western half of the island in 1859. During World War II, Imperial Japan occupied East Timor, but Portugal took back control after Japan surrendered.

East Timor declared its independence from Portugal in 1975, but Indonesia invaded it soon after. The country then became a province of Indonesia. During the 24-year occupation, many people died. From 1975 to 1999, about 102,800 people died due to the conflict, mostly from hunger and illness.

In 1999, the people of East Timor voted overwhelmingly for independence in a referendum organised by the UN. Right after the vote, groups against independence, supported by the Indonesian military, started a destructive campaign. They killed about 1,400 Timorese and forced 300,000 people to flee to West Timor as refugees. Most of the country's buildings and roads were destroyed. The International Force for East Timor (INTERFET) arrived to stop the violence. After a period managed by the United Nations, East Timor became an independent country in 2002. It is one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia, with many people out of work and unable to read or write.

Contents

Early History of Timor

The island of Timor was settled by people moving across Australasia. The oldest signs of human life are from about 43,000 to 44,000 years ago, found in the Laili cave. These early people were skilled at sea, catching large deep-sea fish like tuna. One of the world's oldest fish hooks, from 16,000 to 23,000 years ago, was found in the Jerimalai cave.

It is believed that people from three different groups still live in East Timor today. The first group is described as Veddo-Australoid people. Around 3000 BC, a second group, the Melanesians, arrived. The Veddo-Australoid people then moved to the mountains. Finally, proto-Malays came from southern China and northern Indochina. Timorese stories say their ancestors sailed around the eastern end of Timor and landed in the south.

These different groups, along with the island's mountains, led to many different languages and cultures. What is now East Timor was once divided into as many as 46 small kingdoms. However, big Islamic powers from Java to the west did not have much influence here.

Later Timorese people were not seafarers; they focused on land and rarely contacted other islands. Timor was part of a group of small islands with small populations. Trade with the outside world happened through foreign traders from places like China and India. They brought metal goods, rice, fine clothes, and coins. In return, they took local spices, sandalwood, deer horn, beeswax, and slaves.

Several old forts found in Timor were built between 1000 and 1300. Changes in climate and more trade in sandalwood may have caused more arguments over resources during that time.

The first known mention of Timor in writing is in the 13th-century Chinese book Zhu Fan Zhi. It calls Timor Ti-Wen and notes its sandalwood. In 1365, the Nagarakretagama mentions Timor as an island within the Majapahit Empire. However, a Portuguese writer in the 1500s said that all islands east of Java were called "Timor."

Early European explorers reported that Timor had many small chiefdoms in the early 1500s. One important kingdom was Wehali in central Timor. The Tetum, Bunaq, and Kemak groups were connected to it. The Magellan expedition, the first trip around the world, visited Timor. They noted that people from Luzon, Philippines, traded in East Timor for sandalwood.

Portuguese Rule in East Timor

The first Europeans to arrive were the Portuguese traders, who landed near what is now Pante Macassar between 1512 and 1515. However, it was not until 1556 that a group of Dominican friars started their missionary work, settling in Solor to the north. Wars with the Netherlands reduced Portuguese control in the Malay islands. They were mostly limited to the Lesser Sunda Islands. Later wars further reduced their power, with Solor falling in 1613 and Kupang in western Timor in 1653.

By the 1600s, the village of Lifau in the Oecussi area became the center of Portuguese activities. Around this time, the Portuguese began to convert the Timorese to Catholicism. In 1642, a military group led by Francisco Fernandes, a Portuguese, aimed to weaken the power of the Timor kings. This group, made up of 'Black Portuguese' (called Topasses), helped spread Portuguese influence into the country's interior. In 1702, a Governor was appointed for Solor and Timor, based in Lifau.

Portuguese control was weak. They faced opposition from Dominican friars, the Topasses, local kingdoms, and sultanates from South Sulawesi. A rebellion in 1725 led to a battle in 1726, where Portuguese forces won. In 1769, the Portuguese governor moved his administration from Lifau to what would become Dili. Colonial leaders, mostly in Dili, had to rely on traditional local chiefs for control.

For both Portugal and the Netherlands, Timor was not a high priority. They had little presence outside Dili and Kupang. Still, arguments over their areas of influence led to treaties to set borders. The border between Portuguese Timor and the Dutch East Indies was officially decided in 1859 with the Treaty of Lisbon. Portugal received the eastern half, along with the Oecussi area on the north coast. This treaty also saw Portugal take control of Maubara, where the Dutch had started coffee farming.

In 1844, Timor was separated from Portuguese India's control. In 1863, Dili was declared a city, and East Timor became directly under the government in Lisbon. After some changes, it became a full province in 1909.

From 1910 to 1912, the East Timorese rebelled against Portugal. Troops from Mozambique and naval ships were brought in to stop the rebels. The final border was drawn in 1914 and is still the border between East Timor and Indonesia today. The Portuguese Timorese pataca became the official money in 1915. Economic problems and not being able to pay salaries led to a small revolt in 1919.

For Portugal, East Timor was mostly a neglected trading post until the late 1800s. There was very little investment in roads, health, and education. The island was also used to send people the government saw as "problems," like political prisoners and criminals. The Portuguese ruled through local chiefs called liurai. Sandalwood was the main export, with coffee becoming important in the mid-1800s. Where Portuguese rule was strong, it was often harsh. In the early 1900s, Portugal's own economy struggled, so they tried to get more wealth from their colonies.

Portuguese Timor was a place where political opponents from Portugal were sent into exile. Many of these were anarchists. The main times people were sent to Timor were in 1896, 1927, and 1931. Some of them continued their resistance even in exile. After World War II, the remaining exiles were allowed to return home.

Even though Portugal was neutral during World War II, Australian and Dutch forces occupied Portuguese Timor in December 1941. They expected a Japanese invasion. This Australian action brought Portuguese Timor into the Pacific War and slowed down the Japanese. When the Japanese did occupy Timor in February 1942, a small Dutch-Australian force and many Timorese volunteers fought them in a guerrilla war for a year. After the allies left in February 1943, the East Timorese continued fighting the Japanese. This help cost the people a lot: Japanese forces burned many villages and took food. The Japanese occupation led to the deaths of 40,000–70,000 Timorese.

Portuguese Timor was given back to Portugal after the war, but Portugal continued to neglect the colony. Very little money was spent on roads, education, and healthcare. The colony was called an 'Overseas Province' of Portugal in 1955. Local power was with the Portuguese Governor and a council, as well as local chiefs. Only a few Timorese were educated, and even fewer went to university in Portugal.

During this time, Indonesia did not show interest in Portuguese Timor. This was partly because Indonesia was busy trying to gain control of West Irian (now Papua). In fact, at the United Nations, Indonesian diplomats said their country did not want control over any land outside the former Dutch East Indies, specifically mentioning Portuguese Timor.

In 1960, East Timor gained the right to decide its own future under international law. It kept this status, with Portugal as the managing power, even during Indonesian rule.

The small 1959 Viqueque rebellion saw rebels trying to get support from outside their local area. Their calls for better services and rights led to some changes in Portuguese policy, like more education and jobs. Basic schooling increased, and more advanced schools were available to those with more Portuguese connections. Important schools included a Catholic school in Soibada and the Seminary of Our Lady of Fatima in Dare. The politicians who became important at the end of Portuguese rule often studied in these schools. This "Timorisation," which meant more local people in administration and the military, mostly helped the upper class and did not change much for most people.

Path to Independence

The process of decolonisation started by the Portuguese revolution in 1974 meant Portugal effectively left its colony of Portuguese Timor. A civil war broke out in 1975 between supporters of Portuguese Timorese political parties: the left-wing Fretilin and the right-wing UDT. The UDT tried a coup, which Fretilin resisted with help from local Portuguese military.

One of the first actions of the new government in Lisbon was to appoint a new governor for the colony, Mário Lemos Pires, in November 1974. He would be the last governor of Portuguese Timor. One of his first decisions was to make political parties legal to prepare for elections in 1976. Three main parties were formed:

- The União Democrática Timorense (UDT, Timorese Democratic Union) was supported by traditional leaders. They first wanted to stay connected with Lisbon, but later aimed for gradual independence. One of its leaders, Mário Viegas Carrascalão, later became the Indonesian Governor of East Timor.

- The Associação Social Democrática Timorense (ASDT, Timorese Social Democratic Association) wanted quick independence. It later changed its name to Frente Revolucionária de Timor-Leste Independente (Revolutionary Front of Independent East Timor or Fretilin). Many in Australia and Indonesia saw Fretilin as Marxist. The party aimed for "the universal doctrines of socialism."

- The Associação Popular Democrática Timorense ("Apodeti", Timorese Popular Democratic Association) supported joining Indonesia as an independent province, but had little support from ordinary people. One of its leaders, Abílio Osório Soares, later served as the last Indonesian-appointed Governor of East Timor. Apodeti got some support from local chiefs in the border area, some of whom had worked with the Japanese during World War II. It also had some support from the small Muslim minority, though Marí Alkatiri, a Muslim, was a key Fretilin leader and became prime minister in 2002.

Other smaller parties included Klibur Oan Timur Asuwain (KOTA, meaning 'Sons of the Mountain Warriors'), which wanted a type of monarchy with local chiefs, and the Partido Trabalhista (Labour Party). Neither had much support, but they later worked with Indonesia. The Associação Democrática para a Integração de Timor-Leste na Austrália (ADITLA) wanted to join Australia, but stopped after the Australian government said no.

During this time, the leaders of the new political parties started to feel a shared national identity. The main parties all promoted freedom of speech, assembly, and religion. Fretilin specifically tried to create a strong national identity, calling it maubere.

Parties Compete, Other Countries Get Involved

Indonesia and Australia watched what was happening in Portuguese Timor very closely in 1974 and 1975. Suharto's "New Order" government in Indonesia was worried about Fretilin becoming too left-leaning. They feared a small independent leftist state in the middle of their islands could inspire other parts of Indonesia to seek independence.

Australia's Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, had a close relationship with the Indonesian leader. He also watched events with concern. In 1974, he told Suharto that an independent Portuguese Timor would be "an unviable state, and a potential threat to the stability of the region." He thought joining Indonesia would be best for Portuguese Timor.

In local elections on 13 March 1975, Fretilin and UDT became the largest parties. They had previously formed an alliance to campaign for independence.

Indonesian military intelligence tried to create divisions between the pro-independence parties and support Apodeti. This was called Operasi Komodo. Many Indonesian military figures met with UDT leaders, making it clear that Indonesia would not accept a Fretilin-led government in an independent East Timor. The alliance between Fretilin and UDT later broke up.

During 1975, Portugal became less involved in its colony's politics. It was busy with civil unrest and political problems at home, and more focused on decolonising its African colonies like Angola and Mozambique. Many local leaders in Timor thought independence was not realistic and were open to talks with Indonesia about joining their country.

The Coup and Declaration of Independence

On 11 August 1975, the UDT launched a coup to stop Fretilin's growing popularity. Portuguese Governor Mário Lemos Pires fled to the island of Atauro, north of Dili. From there, he tried to make a deal between the two sides. Fretilin urged him to return and continue the decolonisation process, but he said he was waiting for instructions from Lisbon, which was becoming less interested.

Indonesia tried to make the conflict look like a civil war that had caused chaos in Portuguese Timor. However, after only a month, aid groups from Australia and other places visited and reported that the situation was stable. Still, many UDT supporters had fled into Indonesian Timor, where they were forced to support joining Indonesia. In October 1975, in the border town of Balibo, two Australian television crews (the "Balibo Five") reporting on the conflict were killed by Indonesian forces. They had seen Indonesian troops entering Portuguese Timor.

While Fretilin wanted the Portuguese governor to return, the worsening situation meant they had to ask the world for support on their own. On 28 November 1975, Fretilin declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of East Timor. This was not recognised by Portugal, Indonesia, or Australia. However, six countries with leftist governments did recognise it. Fretilin's Francisco Xavier do Amaral became the first president, and Nicolau dos Reis Lobato was prime minister.

Indonesia responded by having UDT, Apodeti, KOTA, and Labour Party leaders sign a declaration asking to join Indonesia. This was called the Balibo Declaration, but it was written by Indonesian intelligence and signed in Bali, Indonesia, not Balibo, East Timor. Xanana Gusmão, who later became East Timor's prime minister, called it the 'Balibohong Declaration', a play on the Indonesian word for 'lie'.

East Timor Solidarity Movement

An international East Timor solidarity movement grew after the 1975 invasion and occupation by Indonesia. This movement was supported by churches, human rights groups, and peace activists. It grew its own organisations in many countries. Many protests and vigils supported actions to stop military supplies to Indonesia. The movement was strongest in nearby Australia, in Portugal, the Philippines, and former Portuguese colonies in Africa. It also had a significant impact in the United States, Canada, and Europe.

José Ramos-Horta, who later became president of East Timor, said in 2007 that the solidarity movement "was instrumental. They were like our peaceful foot soldiers, and fought many battles for us."

Indonesian Invasion and Annexation

The Indonesian invasion of East Timor began on 7 December 1975. Indonesian forces launched a huge attack by air and sea, called Operasi Seroja. They mostly used equipment supplied by the US. Declassified documents show that the United States agreed to Indonesia's invasion. When Indonesian President Suharto asked US President Gerald Ford for understanding about taking quick action in East Timor, Ford replied, "We will understand and not press you on the issue. We understand the problem and the intentions you have."

The Australian government did not react to this invasion. This might have been because of oil found in the waters between Indonesia and Australia. This lack of action led to big protests by Australian citizens, who remembered the Timorese people's brave actions during World War II.

Indonesia gave reasons for the invasion, including the possibility of a communist government, the need to develop the area, and national security risks. Public statements denied that the invasion was meant to take the territory. They said they still supported the right to self-determination. Elections were held under Indonesian pressure, and on 17 December, Indonesia said an East Timorese Provisional Government would be formed.

The United Nations Secretary General's Special Representative tried to visit areas held by Fretilin from Darwin, Australia, but the Indonesian military blocked him. On 31 May 1976, the government chose 37 people to form a 'People's Assembly' in Dili. This assembly voted to join Indonesia, making it seem like a choice by the people. On 17 July, East Timor officially became the 27th province of Indonesia (Timor Timur).

However, the occupation of East Timor remained a public issue in many countries, especially Portugal. The UN never recognised the Indonesian government in Timor or the annexation. The UN General Assembly passed a resolution on 12 December 1975, saying it "deplores the military intervention of the armed forces of Indonesia in Portuguese Timor and calls upon the Government of Indonesia to withdraw without delay its armed forces from the Territory." From 1975 to 1982, the General Assembly each year said East Timor had the right to decide its own future. Portugal remained the recognised authority, and Indonesian forces were asked to leave. José Ramos-Horta represented FRETILIN at the UN, campaigning for independence.

Despite this international opposition, few actions were taken to support independence. Many countries quietly accepted Indonesian control. Australia even officially recognised the annexation and downplayed the deaths of five Australian journalists during the invasion. These actions were to stay on good terms with Indonesia, especially during the Cold War. The United States held joint military drills with Indonesia before the invasion. At the time of the invasion, about 90% of Indonesia's weapons came from the United States. Military support continued and even increased after the invasion.

Resistance moved to the interior, where FRETILIN continued to hold land. In 1976, these areas were divided into six sectors, each with civilian and military leaders. Indonesian campaigns slowly captured these areas, completing the conquest in 1978.

Indonesia spent a lot of money in Timor-Leste, leading to faster economic growth. However, the Timorese people never accepted Indonesia's strong, direct rule. They wanted to keep their own culture and national identity. By 1976, there were 35,000 Indonesian troops in East Timor. Falintil, Fretilin's military group, fought a guerrilla war with success at first but became much weaker later. The cost of the takeover to the East Timorese was huge. It is estimated that at least 100,000 people died in the fighting, and from disease and famine. Other reports say between 60,000 and 200,000 died during the 24-year occupation. A detailed report for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor said about 102,800 conflict-related deaths happened from 1974–1999.

By 1989, Indonesia had firm control and opened East Timor to tourism. Then, on 12 November 1991, Indonesian troops fired on protesters at the Santa Cruz Cemetery in Dili. The protesters were remembering an independence activist who had been killed. This event was filmed and shown around the world. The Indonesian government admitted to 19 killings, but it is thought over 200 died in the massacre. While Indonesia introduced a civilian government, the military remained in control. With help from secret police and Timorese militias, reports of arrests and murders were common.

Towards Independence

Timorese groups fought a resistance campaign against Indonesian forces for East Timor's independence. Many terrible acts and human rights violations by the Indonesian army were reported. Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono admitted in 2008 that Indonesia was guilty of these. Foreign powers like the Australian government wanted to keep good relations with Indonesia. They were often unwilling to help the push for independence, even though many Australians felt sympathy for the East Timorese. However, when President Suharto left power and the Howard government in Australia changed its policy in 1998, a vote on independence was proposed. The Portuguese government's continued lobbying also helped.

Impact of the Dili Massacre

The Dili Massacre on 12 November 1991 was a turning point for sympathy towards pro-independence East Timorese. A growing East Timor solidarity movement developed in Portugal, Australia, and the United States. After the massacre, the US Congress voted to stop funding military training for Indonesian soldiers. However, the US continued to sell weapons to the Indonesian National Armed Forces. President Bill Clinton stopped all US military ties with Indonesia in 1999. The Australian government also cut ties in 1999.

The Massacre deeply affected public opinion in Portugal. This was especially true after TV footage showed East Timorese praying in Portuguese. Independence leader Xanana Gusmão gained widespread respect. He was given Portugal's highest honour in 1993, after he had been captured and imprisoned by the Indonesians.

Australia's difficult relationship with the Suharto government was highlighted by the Massacre. In Australia, there was also widespread public anger and criticism of Canberra's close relationship with Indonesia and its recognition of Indonesia's control over East Timor. This embarrassed the Australian government. However, Foreign Minister Gareth Evans played down the killings, calling them "an aberration, not an act of state policy." Prime Minister Paul Keating (1991–1996) visited Indonesia in April 1992 to improve trade and cultural relations. But the repression of the East Timorese continued to harm cooperation between the two nations.

Australian governments saw good relations and stability in Indonesia (Australia's largest neighbour) as important for Australia's security. Still, Australia provided a safe place for East Timorese independence supporters like José Ramos-Horta, who lived in Australia during his exile.

The fall of President Suharto and the arrival of President B. J. Habibie in 1998 brought political reform towards a more democratic system in Indonesia. In June 1998, facing pressure, Indonesia offered East Timor some independence within the Indonesian state. However, it said Portugal and the UN must recognise Indonesian control.

Role of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church in East Timor played a very important role during the Indonesian occupation. In 1975, only 20% of East Timorese were Catholic. But by the end of the first decade after the invasion, this number jumped to 95%. During the occupation, Bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo became a leading voice for human rights in East Timor. Many priests and nuns risked their lives to protect people from military abuses. Pope John Paul II's visit to East Timor in 1989 showed the world what was happening in the occupied territory. It also encouraged independence activists to seek global support.

In 1996, Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and José Ramos-Horta, two key East Timorese activists for peace and independence, received the Nobel Peace Prize. They were awarded for "their work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor." The newly independent nation declared three days of national mourning when Pope John Paul II died in 2005.

International Efforts

Portugal began to put international pressure on Indonesia. It raised the issue with other European Union members and at wider forums like the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. However, other EU countries, like the UK, had close economic ties with Indonesia, including selling weapons. They saw no benefit in strongly raising the issue.

Those supporting East Timorese independence appealed to people in Western countries as well as governments. They highlighted their vision of a new state as a liberal democracy. In the mid-1990s, the pro-democracy People's Democratic Party (PRD) in Indonesia called for Indonesia to leave East Timor. The party's leaders were arrested in July 1996.

In July 1997, visiting South African President Nelson Mandela met with Suharto and also with the imprisoned Xanana Gusmão. He urged the release of all East Timorese leaders. Indonesia's government refused but did say it would reduce Gusmão's 20-year sentence by three months.

In 1998, the reformasi movement in Indonesia led to Suharto's resignation. He was replaced by President Habibie, which brought political reform towards a more democratic system. In June 1998, facing more pressure, Indonesia offered East Timor independence within the Indonesian state.

United Nations Administration

On 15 October 1999, the Indonesian People's Consultative Assembly cancelled the law that had annexed East Timor. The administration of East Timor was taken over by the UN through the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET), which started on 25 October. All remaining Indonesian forces left the territory in November. The INTERFET mission ended on 14 February 2000, with military command transferred to the UN.

The UNTAET mission was bigger than previous UN peacekeeping efforts. UNTAET effectively governed during this time. It worked to build new institutions and local skills, as well as handling immediate humanitarian and security needs. There were some challenges, like a fast timeline and not enough involvement with local leaders. Reconstruction efforts included rebuilding the education system. For this, textbooks were bought in the new official language, Portuguese, even though many teachers and students could not speak it.

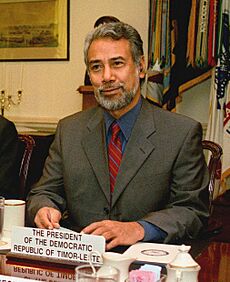

Elections were held in late 2001 for a group to write a constitution. This was finished in February 2002. East Timor officially became independent on 20 May 2002. Xanana Gusmão was sworn in as the country's first president. East Timor became a member of the UN on 27 September 2002.

The Independent Republic

The destruction and violence not only ruined the country's buildings and economy but also reduced its human resources. José Ramos-Horta said, "we are starting from absolutely ground zero." The early economy depended on money from other countries. In 2004, most people who earned wages worked for the government, the UN, or aid groups. The small private sector was mostly security services.

Relations with Indonesia have been friendly. The two countries have defined most of their borders. In 2005, a report on human rights violations during Indonesian rule was released. In 2008, the Indonesia–Timor Leste Commission of Truth and Friendship confirmed most of these findings.

Australia–East Timor relations have been difficult due to arguments over the maritime boundary between the two countries. Australia claims oil and natural gas fields in an area called the 'Timor Gap', which East Timor believes is within its sea borders.

2006 Crisis

Unrest began in the country in April 2006 after riots in Dili. A protest supporting 600 East Timorese soldiers, who were fired for leaving their barracks, turned into riots. Five people were killed, and over 20,000 fled their homes. Fierce fighting broke out in May 2006 between government troops and unhappy soldiers. The reasons for the fighting seemed to be about how oil money was shared and the poor organisation of the Timorese army and police. Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri called the violence a "coup" and welcomed help from other countries. By 25 May 2006, Australia, Portugal, New Zealand, and Malaysia sent troops to Timor to stop the violence. At least 23 people died.

On 21 June 2006, President Xanana Gusmão formally asked Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri to step down. Most Fretilin party members demanded the prime minister's resignation, accusing him of lying about giving weapons to civilians. On 26 June 2006, Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri resigned. In August, rebel leader Alfredo Reinado escaped from prison. Tensions rose again after fights between youth gangs forced the closure of Presidente Nicolau Lobato International Airport in late October.

In April 2007, Gusmão decided not to run for president again. Before the April 2007 presidential elections, there were new outbreaks of violence in February and March 2007. José Ramos-Horta became president on 20 May 2007, after winning the election. Gusmão became prime minister on 8 August 2007. President Ramos-Horta was badly hurt in an assassination attempt on 11 February 2008. This was a failed coup, seemingly by Alfredo Reinado, a rogue soldier who died in the attack. Prime Minister Gusmão also faced gunfire but was unharmed. The Australian government immediately sent more troops to East Timor to keep order.

From the 2010s

New Zealand announced in early November 2012 that it would remove its troops from the country. They said East Timor was now stable and calm. Five New Zealand troops died during the 13 years their country had a military presence in East Timor.

Francisco Guterres of the centre-left Fretilin party was the president of East Timor from May 2017 until May 2022. The main party of the AMP coalition, National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction, led by independence hero Xanana Gusmão, was in power from 2007 to 2017. However, Fretilin leader Mari Alkatiri formed a coalition government after the July 2017 parliamentary election. But this new government soon fell, leading to a second general election in May 2018. In June 2018, former president and independence fighter Jose Maria de Vasconcelos, known as Taur Matan Ruak, became the new prime minister.

The Nobel prize winner, former president José Ramos-Horta, won the April 2022 presidential election against the current president, Francisco Guterres. In May 2022, Ramos-Horta was sworn in as East Timor's president.

United Nations Missions

- UNAMET United Nations Mission in East Timor: June—October 1999

- UNTAET United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor: October 1999 – May 2002

- UNMISET United Nations Mission of Support to East Timor: May 2002 – May 2005

- UNOTIL United Nations Office in Timor Leste: May 2005 – August 2006

- UNMIT United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste: August 2006 – December 2012

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Timor Oriental para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Timor Oriental para niños

- Timeline of East Timorese history

- List of years in East Timor

- List of rulers of Timor

- History of Asia

- History of Southeast Asia

- History of Indonesia

- Politics of East Timor

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |