Invasion of Corsica (1794) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Invasion of Corsica |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

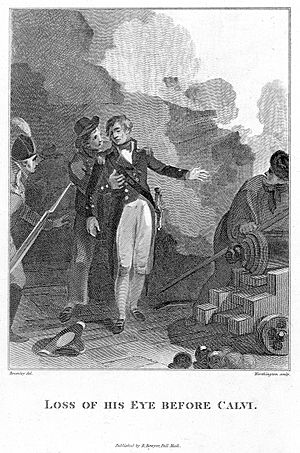

Loss of his Eye Before Calvi, National Maritime Museum |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The invasion of Corsica was a military campaign in 1794. British and Corsican forces worked together. They fought against French soldiers during the French Revolutionary Wars. The main goal was to capture three important towns in Northern Corsica: San Fiorenzo, Bastia, and Calvi.

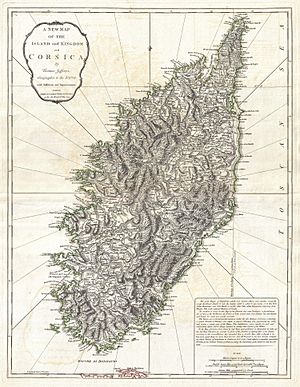

These towns were surrounded, attacked, and bombarded. By August 1794, the French forces were completely driven out of the island. Corsica is a large island in the Ligurian Sea. Controlling it meant controlling the seas near Southern France and Northwestern Italy. This area was very important in the early French Revolutionary Wars.

The British commander, Lord Hood, believed controlling Corsica was key. It would help him block the French fleet in Toulon. France had taken over Corsica in 1768. Many Corsicans were unhappy about this. The French Revolution in 1789 made them want independence even more. Their leader, Pasquale Paoli, asked Lord Hood for help. Hood was busy with the Siege of Toulon at first. But in early 1794, he focused on Corsica.

British forces used ships to bombard the coast. Soldiers and marines landed on the island. Corsican fighters also helped them. They attacked San Fiorenzo, forcing the French to leave. The French then went to Bastia. Hood then led his forces to Bastia and surrounded it. The town surrendered after 37 days. After this victory, the Corsican people, led by Paoli, joined forces with Britain. More British soldiers arrived. They then attacked the last French fort in Calvi. It was bombarded for two months and finally surrendered in August 1794.

Corsica was useful for the British fleet. Its harbors offered a place for ships to rest and resupply. However, Corsican politics were unstable. The French also kept trying to take the island back. This used up a lot of British resources. By late 1796, France was winning battles in Northern Italy. Spain also declared war on Britain. So, Britain could no longer hold Corsica. British forces left the island. The French quickly took control of Corsica again.

Contents

Why Corsica Was Important

Corsica is a big, mountainous island. It is located in the Ligurian Sea. This sea is part of the Mediterranean Sea. It is near Spain, France, and Italy. If a navy controls Corsica, especially the harbor at San Fiorenzo, it can control this important waterway.

For many years, Corsica was part of Genoa. But by the mid-1700s, it was mostly independent. It was called the Corsican Republic, led by Pasquale Paoli. Genoa couldn't control Paoli. So, they sold Corsica to France in 1768. France then invaded and took over the island.

After the French Revolution in 1789, things changed. The idea of a republic spread. This made Corsicans want independence again. Paoli, who had been away for 22 years, returned. He quickly defeated his rivals in Corsica. This included the famous Bonaparte family. Paoli took control of the island again.

By early 1793, France was going through a tough time. Paoli was worried about being arrested by French leaders. So, he told his followers to form fighting groups. These groups quickly pushed the French soldiers into three northern towns. These were San Fiorenzo, Calvi, and the capital, Bastia. Paoli then looked for help from other countries.

Great Britain joined the French Revolutionary Wars in January 1793. France had declared war on Britain. Britain had important trade interests in the Mediterranean. So, a large British fleet was sent to block the French fleet. The French fleet was based in Toulon. The closest British port was Gibraltar. This was too far to be a good base for the blockade. Britain had once controlled Minorca as a base. But they lost it during the American Revolutionary War. Corsica was often suggested as a new base. Henry Dundas, a British leader, liked this idea. British agents in Italy had already talked to Paoli. Then, the British fleet, led by Lord Hood, arrived in August 1793.

However, Corsica was not Hood's main focus at first. Soon after he arrived, the people of Toulon turned against their French government. With British support, they declared loyalty to the old French monarchy. Hood's fleet entered the port. They took control of the French fleet there. They also put soldiers in the forts. For four months, Hood tried to hold Toulon. He had a mix of French, British, and Italian troops. But a French army, partly led by Napoleon Bonaparte, slowly took over the defenses. On December 18, 1793, the French captured the high ground near the harbor. The British fleet had to leave quickly. They took thousands of French people who supported the monarchy with them. The British tried to burn the captured French ships. But they only partly succeeded. Many of these refugees later landed in Corsica.

Early Fights in Corsica (1793)

Paoli asked Hood for help. So, Hood sent a small group of ships to Corsica. Commodore Robert Linzee led them. He was told to ask the French soldiers in Bastia and Calvi to surrender. When they refused, he tried to capture San Fiorenzo. Linzee sailed his ships into the bay on September 19. He captured the Torra di Mortella, a tower that guarded the harbor.

On October 1, he attacked another tower, the Torra di Fornali. But this tower was well-defended. Linzee's ships came under heavy fire. He had to pull back with many injured sailors. Many injuries were caused by special "heated shot." These were cannonballs made red-hot before firing.

In late October, French ships tried to bring more soldiers to Corsica. They escaped an attack by the British ship HMS Agamemnon. Captain Horatio Nelson commanded this ship. The French soldiers landed at San Fiorenzo and Bastia. With these new troops, the French launched small attacks. They recaptured the town of Farinole and most of the Cap Corse area. Linzee stayed offshore. His ships blocked the harbor, trapping the French ships. But small boats from Italy could still get through. Paoli complained about this.

More British ships, led by Nelson, were sent to stop these boats. Nelson attacked the Corsican coast. He destroyed the island's only mill. He also burned a convoy of wine. But after only two weeks, Nelson was ordered to leave. He had to help Hood with the evacuation of Toulon.

Now, the British needed another base in the Mediterranean. Paoli offered Corsica to Hood. He suggested it become a self-governing part of the British Empire. It would be like the Kingdom of Ireland. In early January 1794, Hood sent two officers, Edward Cooke and Thomas Nepean. They were to talk to Paoli and see if he could be trusted. The officers returned with very hopeful reports. They thought the French towns were not well-defended. They also thought there were fewer French soldiers. Paoli said there were only 2,000 French troops. But there were actually more than 4,500 soldiers. They were split among the three towns.

Hood was convinced by Paoli's offer. He sent Sir Gilbert Elliot to work out the details. He also sent Lieutenant-Colonel John Moore and engineer Major George Koehler to help with military plans. In early February, Hood sailed from his temporary base. He ordered the invasion of Corsica to begin.

British Landings in Corsica

Taking San Fiorenzo

Major-General David Dundas was the British Army officer in charge. Dundas was careful and often worried. He and Hood had disagreed before. Paoli suggested attacking San Fiorenzo first. This was where Linzee had been defeated six months earlier.

On February 7, British troops landed on the coast. They landed west of the Torra di Mortella without any fighting. On February 8, a small group of British ships attacked the Torra di Mortella from the sea. But it didn't work well. The ship HMS Fortitude was hit by heated shot. An ammunition box caught fire. Six men died, and 56 were injured. The plan to attack from the sea was stopped. Instead, British sailors, led by Moore, built cannons on land. On February 10, artillery fire from these cannons set the tower on fire. The French soldiers inside surrendered. Moore then marched his forces and cannons overland. They attacked the nearby Convention Redoubt. They successfully captured it on February 17. The town and ships in the harbor were now in danger. The French left the next day. They sank two of their ships in the bay.

The Siege of Bastia

The French soldiers retreated over the Serra mountains to Bastia. They avoided Corsican forces trying to stop them. This started the second part of the invasion, targeting Bastia. The attack on Bastia was delayed. Hood and Dundas argued about how to block the town. Dundas resigned and Colonel Abraham D'Aubant replaced him in March.

So, the attack didn't happen until April 4. A force of 1,450 British troops landed north of the town. Colonel William Villettes and Captain Nelson led them. Hood placed the main British fleet near the harbor. They kept blocking the town with a smaller group of ships. On April 11, a naval attack on the town failed. The town's cannons drove off the ships. The small ship HMS Proselyte was sunk.

For 14 days, the town was bombarded. Moore had built cannons on the high ground overlooking the defenses. Hood was eager for the French commander, Lacombe-Saint-Michel, to surrender. On April 25, Hood ordered D'Aubant to storm the town. But the army commander refused. Hood decided to starve the defenders out instead. On May 12, Lacombe-Saint-Michel escaped the town and returned to France. Ten days later, food was running low. Nearly a quarter of the soldiers were sick or injured. His second-in-command, Antoine Gentili, surrendered to Hood. The French soldiers were allowed to return safely to France. This agreement was very unpopular with the Corsicans. They protested strongly, but they were ignored.

After Bastia surrendered, Paoli agreed to British control of Corsica. On June 1, elections were held. The island's parliament met for the first time on June 16. They announced a new constitution. Paoli's assistant, Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo, became president. Elliot became the acting viceroy. The constitution allowed many men to vote. It also had elections every two years. Paoli had strong power through Pozzo di Borgo. But within weeks, the government had problems. Elliot and Pozzo di Borgo argued. They disagreed about how Corsicans treated French supporters on the island.

The Final Battle at Calvi

The last part of the campaign was to capture Calvi. This was a fortified port on the northwestern coast of Corsica. The French commander in Corsica, Raphaël de Casabianca, was in charge there. Calvi had two modern forts protecting it. To the west was Fort Mozello, a star fort with an outside battery. To the southwest was Fort Mollinochesco. This fort watched the main road from inside Corsica. In the Bay of Calvi, two French ships were ready to fire on any attacking force.

British forces landed on June 17 outside the town. Charles Stuart and Nelson led them. They dragged cannons over the mountains. They set up batteries overlooking the forts. Hood was away for most of the siege. The French fleet had sailed from Toulon in June. Hood was busy blocking them in Gourjean Bay.

By July 6, Mollinochesco was badly damaged. The soldiers inside moved into Calvi. The British then focused on Mozello. They bombarded it for twelve days. A large hole was made in the walls of Mozello. But the French fired back. This caused many injuries among the British gun crews. Nelson was one of them; he was blinded in one eye. On July 18, Stuart ordered Moore and David Wemyss to attack the fort. They captured it after fierce hand-to-hand fighting on the walls.

The British then heavily bombarded the town. This caused much damage and many injuries. In late July, there were talks and a truce. But supplies arrived at Calvi at the end of the month. This caused fighting to start again briefly. Finally, with little food and ammunition left, Casabianca officially surrendered. He received the same terms as Bastia. By the time of the surrender, only about 400 British soldiers were fit to fight. Many were sick with malaria and dysentery. This siege was important for Nelson's career. His leadership here led to more command opportunities later.

What Happened Next

With the French gone, Corsica became a self-governing part of the British Empire. Hood used San Fiorenzo as a place for his fleet to anchor. But it didn't have good ship repair facilities. Danger from the sea was always a worry. In August 1794, the British ship HMS Scout was protecting Corsican fishing boats. Two French ships attacked and captured it. The fishing boats scattered. Several were seized by pirates. Their crews were taken captive. A British envoy, Frederick North, later helped free them.

In early 1795, France tried to land 25,000 soldiers on Corsica. But the British fleet defeated them at the Battle of Genoa. For the rest of the British time on the island, French privateers (ships allowed to attack enemy ships) and agents often landed on the coast.

After the successful invasion, problems started in Bastia, the island's capital. There were many arguments between British leaders. First, Stuart and Elliot argued over who controlled the military. Stuart eventually resigned. At the same time, Elliot tried to stop Paoli from punishing French supporters. This went against the surrender terms.

These disagreements grew worse. In 1795, the British set up a special group. It was supposed to investigate crimes. But it also looked into acts against the British. This went against the constitution agreed the year before. It made many people unhappy. Also, the British didn't keep promises about improving the island. And Paoli and Pozzo di Borgo argued more. In 1795, Paoli set up a rival government in Rostino. He also had many supporters in the Bastia parliament. His nephew, Leoni Paoli, led them. In July 1795, these arguments exploded. A statue of Paoli was publicly made fun of by some of Elliot's Corsican friends. Riots and protests spread across the island. A civil war was almost avoided when Paoli left for Britain in October.

In 1796, Corsicans were also unhappy about British taxes. In March, some people in the central mountains rebelled. This was around the Corte area. For several months, there was fighting. Rebels fought Corsican government forces. The British had a successful attack at Ajaccio. Another attack near Bastia failed. Eventually, Elliot couldn't crush the rebellion easily. French agents were also openly working on the island. Elliot made peace with some rebels and calmed others. By October, things were more stable.

But the situation in the Mediterranean was getting worse. British forces were spread thin. Napoleon Bonaparte was winning many battles in Italy. In August 1796, Spain signed a treaty with France. They declared war on Great Britain. The British forces in the Mediterranean were far from home. Their supply lines were long and open to attack. Now, a large and powerful enemy was behind them. Gibraltar was especially in danger. Orders were sent to Elliot right away. He was told to take British soldiers from Corsica to defend Gibraltar.

When news reached Corsica in October, the rebellions spread. Groups wanting revolution appeared in towns. They started talking to French forces in Italy. On October 14, Nelson forced the groups in Bastia to break up. He threatened violence if they didn't. But French troops had already landed at Macinaggio. On October 19–20, Elliot and the remaining British military and diplomats left. About 370 Corsican refugees also left. They sailed with Nelson's ships to Portoferraio. Over the next week, the remaining soldiers in Calvi and San Fiorenzo left. The defenses of San Fiorenzo were purposely destroyed. By this time, French troops, led by Antoine Gentili, had already captured most of the island with Corsican help. In December 1796, the British fleet, now led by Sir John Jervis, left the Mediterranean completely.

Eight years later, Britain was planning defenses against a possible invasion by Napoleon. They remembered how well the Torra di Mortella tower had resisted in 1794. Old drawings of the tower were found. Based on these designs, over a hundred towers were built. They were placed along the south and east coasts of Britain. These towers became known as Martello Towers. The name came from a mixed-up translation. By the time they were finished, the invasion threat was over.

Images for kids

-

Loss of his Eye Before Calvi, National Maritime Museum

-

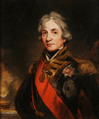

Lord Nelson, John Hoppner, c.1805. RNM. Nelson became famous during the Corsican campaign.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |