John Nicholson (East India Company officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Nicholson

|

|

|---|---|

Brigadier General John Nicholson

|

|

| Born | 11 December 1822 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 23 September 1857 (aged 34) Delhi, Bengal Presidency |

| Buried |

Nicholson Cemetery, New Delhi

|

| Allegiance | East India Company |

| Service/ |

Bengal Army |

| Years of service | 1839–1857 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Unit | Bengal Native Infantry |

| Battles/wars | First Anglo-Afghan War First Anglo-Sikh War Second Anglo-Sikh War

|

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath |

| Other work | Colonial administrator |

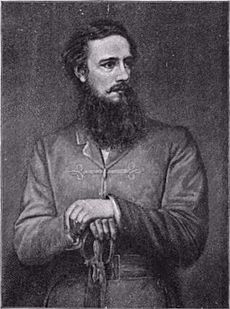

Brigadier General John Nicholson (born December 11, 1822 – died September 23, 1857) was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became very well known during his time serving in British India.

Born in Ireland, Nicholson moved to India when he was young. He joined the East India Company army as an officer. He spent most of his life helping the Company expand its control in many wars. These included the First Anglo-Afghan War and the First and Second Anglo-Sikh War.

Nicholson became a legendary figure as an officer who also helped govern the frontier areas of British India. This was especially true in the Punjab region. He played a key role in setting up the North-West Frontier. His most important moment was his vital role in stopping the Indian Rebellion of 1857. He died during this conflict.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Nicholson was born on December 11, 1822, in Dublin, Ireland. He was the oldest son of Dr. Alexander Jaffray Nicholson and Clara Hogg. When John was nine, his father died. The family then moved to Lisburn, County Antrim.

Nicholson went to school privately and later attended the Royal School Dungannon. His uncle, Sir James Weir Hogg, helped him. His uncle was a successful lawyer for the East India Company. John left school when he was just over sixteen. As the oldest boy, he got a chance to join the East India Company army's Bengal Infantry. In early 1839, Nicholson spent a few weeks in London learning about India. He then sailed to India, where he would live for most of his life.

First Experiences in India

Nicholson arrived in India in July 1839. He first joined the 41st Native Infantry. After four months of military training, he became an Ensign in the 27th Native Infantry. This unit was based at Ferozepore.

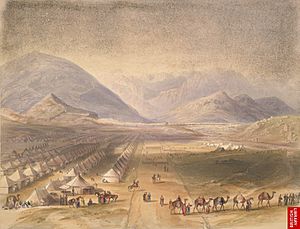

Nicholson arrived too late for the first part of the First Anglo-Afghan War. However, in November 1840, his regiment was sent to Afghanistan. They marched through the Khyber Pass in January 1841.

Afghan War Challenges

Nicholson's regiment was first stationed in Kabul. Then they moved to Ghazni. Here, he met Neville Bowles Chamberlain, who became a close friend. The British had helped Shah Shujah Durrani become king. But the Afghans were angry about his rule.

A revolt started, led by Wazir Akbar Khan. The main British army in Kabul was surrounded. It was then destroyed as it tried to leave Afghanistan in January 1842. This defeat left smaller British groups, like Nicholson's at Ghazni, surrounded by Afghan tribes.

The British commander at Ghazni, Colonel Palmer, surrendered. The Afghans had promised safe passage. But they broke their promise and attacked the British. Nicholson and two other officers were separated. They held off the Afghan attack for two days. They ran out of food and water. Nicholson did not want to surrender because it meant leaving his Indian soldiers (sepoys) to their fate. But he was ordered to surrender. He watched sadly as his sepoys were killed for refusing to change their religion.

Nicholson and ten other British officers were held captive in a dirty cell in Ghazni. They were prisoners from March 10 to August 19, 1842. When the British "Army of Retribution" approached, the prisoners were treated much better. They were taken to Kabul on August 24. There, they even ate with Akbar Khan, the revolt leader. After the Battle of Kabul, Nicholson and the other prisoners were freed in September 1842. They had been held for six long months.

Return and New Mission

Even though the British won, their position in Afghanistan was not safe. The army began the difficult journey back to Peshawar. Nicholson's regiment was part of the rear guard. They were attacked as they moved through the Khyber Pass. On November 1, 1842, Nicholson briefly saw his younger brother, Alexander. He had arrived in India only a few months before.

This difficult experience in the Afghan War deeply affected Nicholson. It made him very determined. He believed it was his duty to spread what he saw as "Christian civilization" in India.

After returning from Afghanistan, Nicholson was stationed first at Peshawar and then at Moradabad for two years. During this time, he focused on military matters and learning the Urdu language. In November 1845, he passed his Urdu exam. He was then sent to the Delhi Field Force. A war with the Sikh Kingdom of the Punjab seemed likely.

Anglo-Sikh Wars and Punjab Service

When the First Anglo-Sikh War began in December 1845, Nicholson was a staff officer. He worked in the supply department for Sir Hugh Gough's army in the Punjab. His main job was to make sure Gough's army had enough food and ammunition.

After the British won the Battle of Sobraon, Nicholson joined Henry Lawrence. He was part of a group of young, driven officers. This group was known as Henry Lawrence's "Young Men". As part of this group, Nicholson gained a lot of power as an officer who also helped govern the North-West Frontier.

His first assignment was in July 1846 in Jammu and Kashmir. He helped strengthen the rule of the British-appointed Maharaja, Gulab Singh. Singh was not popular. Nicholson helped stop a revolt against his rule. He spent the rest of 1846 alone in the Kashmir Valley. He was the only British advisor to Singh. He was relieved when Lawrence called him back to Lahore in February 1847. Nicholson's next important job was helping James Abbott win over tribes in the Hazara region. He did this by leading a daring night raid against a mountain fort.

The Second Sikh War

The murders of Patrick Vans Agnew and Lieutenant William Anderson on April 20, 1848, started a Sikh rebellion across the Punjab. This soon became the Second Anglo-Sikh War. At first, the East India Company was not ready to send its army. This meant officers like Nicholson were on their own.

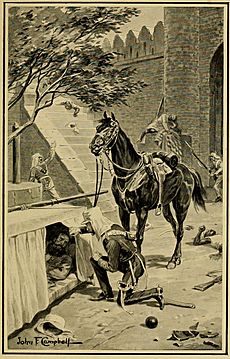

In this difficult situation, Nicholson showed his quick and decisive nature. He left Peshawar with a group of irregular horsemen. He rode straight for the important fort at Attock. If the enemy controlled it, British communication lines would be cut. He arrived at dawn and rode past the surprised Sikh guards. Inside, Sikh soldiers raised their weapons. Nicholson jumped off his horse and took a musket from a soldier. He shouted at them to drop their weapons and leave the fort. The stunned Sikh soldiers quickly obeyed. This action secured the vital fort without a single shot fired. It became the first of Nicholson's famous deeds among the Sikhs.

Days later, he heard a Sikh infantry regiment was moving to join the rebellion. Nicholson left Attock with his trusted irregulars. He found the Sikh force camped at a cemetery. Nicholson rode to their camp and demanded to speak with their Colonel. He gave them one hour to surrender or be "destroyed to a man." The Sikhs argued for an hour in front of Nicholson, who sat still on his horse. After an hour, the Sikhs agreed to surrender. This cemented Nicholson's growing legend among the Sikh people.

Nicholson and other British officers tried to fight the rebellion. But they faced setbacks as they waited for Company troops. Nicholson himself was badly wounded trying to attack a tower held by the Sikhs. By September 1848, Abbott and Nicholson were on the run.

However, the Company Field Army arrived in Lahore in November. Nicholson's younger brother Charles was with them. The situation changed. The British could now attack. Nicholson's irregular troops helped by scouting and securing supply lines. Nicholson fought in the Battle of Chillianwala. He saw the Sikhs surrender at the Battle of Gujrat. He was then ordered to chase the retreating Afghan army back to the Khyber Pass.

After the British took full control of the Punjab, Nicholson became the new Deputy Commissioner at Rawalpindi. He quickly worked to bring "law and order" to the area. In one story, he offered a reward for a troublesome robber chief. When that failed, Nicholson rode alone to the chief's village. He demanded the chief surrender. When the chief refused, Nicholson fought and killed him.

The "Nikal Seyn" Cult

By 1849, Nicholson had been in India for ten years. He was allowed to go home for a year. He traveled around Europe. When he returned to India in January 1852, Lawrence made him the new Deputy Commissioner of the wild Bannu area.

In this role, Nicholson was very strict in bringing peace and order. He had zero tolerance for crime or disrespect towards the government. He often used harsh methods to punish those who broke the law. At first, people feared his strictness. But Nicholson soon earned the respect of the Afghan and North Punjabi tribes. They respected his fairness and honor. He almost completely stopped crime.

The respect Nicholson gained from the Sikh people and Punjabi tribes turned into religious worship. A cult called "Nikal Seyn" developed. They worshipped Nicholson as a saint-like figure. They believed he brought justice to the weak by punishing the strong. This cult even survived in some remote parts of North-West Pakistan into the 21st century. Nicholson, a Christian, was not pleased by this worship. He would whip any followers who practiced this cult in front of him. In 1855, at just thirty-four, Nicholson became the youngest brigadier-general in the Bengal Army. He moved to Peshawar in late 1856 to be the District Commissioner.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

Nicholson was having dinner with his friend Edwardes in Peshawar on May 11, 1857. News arrived that the Indian Mutiny had begun in Delhi. Nicholson and Edwardes immediately planned to form a strong mobile army. This army would be made of European and irregular troops. It could move quickly to stop any outbreaks in the Punjab. Nicholson was calm because he had long distrusted the Bengal Army. He told his fellow officers that mutiny spreads quickly and must be stopped fast.

On May 21, Nicholson heard that the 55th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry had rebelled at Nowshera. He helped disarm the remaining Bengal regiments in Peshawar. Then he went with the force sent to deal with the 55th. The rebels of the 55th retreated from Nowshera. But Nicholson, on his grey horse, chased them with his mounted police and cavalry. He successfully attacked the rebel soldiers. Nicholson chased the fleeing soldiers until nightfall. He killed over 120 of them and captured a similar number. He asked his superiors to show mercy to the Sikh and youngest prisoners.

Nicholson took over command of the Movable Column from Neville Chamberlain. He left Peshawar on June 14 with his personal bodyguards. These horsemen served him out of personal loyalty, not for pay. Nicholson's first act was to disarm any native regiments in his column that he suspected were disloyal.

On July 11, Nicholson stopped a group of rebels who had risen at Sialkot. They had murdered their British officers and civilians. After defeating them in battle, the rebels retreated to an island on the Ravi River. Nicholson had to wait until July 15 to gather enough boats to attack the island. Nicholson's attack was a complete surprise. The British quickly defeated the remaining soldiers.

The Siege of Delhi

The column reached Delhi on August 14. They brought much-needed help to the British army that was surrounding the city. Nicholson found the British forces in Delhi in a bad state. Many were sick or wounded. They were also discouraged by the weak leadership of Colonel Archdale Wilson. However, Nicholson's legendary reputation for dealing with the rebellion greatly boosted the British troops. They saw the young and aggressive Nicholson as the opposite of their old, tired commanders.

Even though he wasn't in command, Nicholson immediately began inspecting the British positions. He started planning how to capture the city. He quickly realized that Wilson was "not at all equal to the crisis" and could not lead the attack. Wilson wanted to wait for a siege train (heavy guns) from Calcutta. However, the rebels sent a force of 6,000 men from Delhi to stop the British train.

In response, Nicholson led a force of about 2,000 men. Their goal was to find and destroy the rebels before they could destroy the British siege train. Nicholson's force reached the rebels first. In the Battle of Najafgarh, Nicholson personally led his troops to defeat the rebel force. This ensured the siege train arrived safely. Nicholson returned to Delhi as a hero.

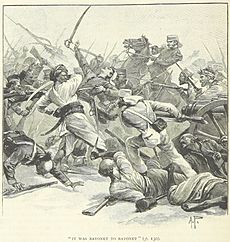

After the siege train arrived, Wilson finally agreed to the other officers' pressure. He allowed the attack to begin at sunrise on September 14. Nicholson was to lead the first troops attacking the breach (a gap in the wall) at the Kashmir Bastion. Under heavy fire from the Indian defenders, Nicholson led his column to the wall. He was the first of his men to climb the breach. He then helped clear the walls of the Mori bastion. But he became separated from his column. Their attack got stuck as they moved further into the city.

Nicholson heard his column was in trouble and that a retreat seemed likely. He rushed to the streets below and began to rally his men. Drawing his sword, Nicholson told his men to follow him. He led a charge down a narrow alley where his troops had been unable to advance. They were trying to capture the Burn Bastion. Just as he looked back to urge his men on, Nicholson was shot by a rebel sniper on a rooftop.

Nicholson's Death

The badly wounded Nicholson was dragged back by soldiers. He first refused to go to the hospital until the city had fallen. But he eventually agreed and was placed in a stretcher. However, in the growing chaos, the stretcher carriers left the injured Nicholson by the side of the road near the Kashmir Gate. A short time later, Lieutenant Frederick Roberts found Nicholson. Nicholson told him, "I am dying; there is no hope for me."

Despite Nicholson's injury, the British held their ground in the city. When he heard that Wilson was losing his nerve and thinking about retreating, Nicholson, who was dying in the hospital, reached for his pistol. He famously declared, "Thank God that I still have the strength yet to shoot him, if necessary."

Nicholson stayed alive until he heard the news that the British had finally taken Delhi. He died from his wounds on September 23, nine days after leading the attack on the city. He was buried the next day in a cemetery between the Kashmir Gate and Ludlow Castle.

Legacy and Memorials

After his death, Nicholson became a hero to the Victorians. He was known as the "Hero of Delhi" and the "Lion of the Punjab." In the years after the rebellion, Nicholson became a household name. Many historians praised his life. However, in recent times, people have looked at Nicholson's legacy differently. They consider his harsh methods of dealing with crime and punishment.

Nicholson's life and death inspired books, songs, and generations of young boys to join the army. He is mentioned in many books, like Rudyard Kipling's Kim and George MacDonald Fraser's Flashman in the Great Game. He also appears as a main character in James Leasor's novel Follow the Drum, which describes his death.

Nicholson's legacy is also seen in the many monuments and statues built in his honor in India and Ireland. These include two statues in Northern Ireland. One is in the center of Lisburn, where Nicholson lived. Another is at the Royal School Dungannon, his old school. Nicholson's obelisk, a large granite memorial, was put up in 1868 in the Margalla hills near Taxila. It pays tribute to his bravery.

Nicholson never married. His closest friend was Herbert Edwardes, who shared his strong Christian faith. At Bannu, Nicholson would ride long distances every weekend to spend time with Edwardes. He even lived in his friend's house for a while when Edwardes' wife was in England. Edwardes and his wife gave comfort and spiritual guidance to Nicholson, who was often lonely. On his deathbed, he sent a message to Edwardes saying he wished Edwardes could be there with him.

A statue of John Nicholson holding a sword was unveiled in Lisburn's Market Square on January 16, 1922. This was the day the last British official formally handed over control of Dublin Castle to the government of the Irish Free State. For Sir James Craig, the first prime minister of Northern Ireland, Nicholson was a symbol of defending the British Empire in both Ireland and India.

A memorial relief (a type of sculpture) by John Henry Foley was placed by his mother sixty years earlier in the town's Cathedral. It shows the final attack on Delhi's Red Fort.

See also

- Sir Henry Lawrence

- James Abbott

- Herbert Benjamin Edwardes

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |