Karl Amadeus Hartmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Karl Amadeus Hartmann

|

|

|---|---|

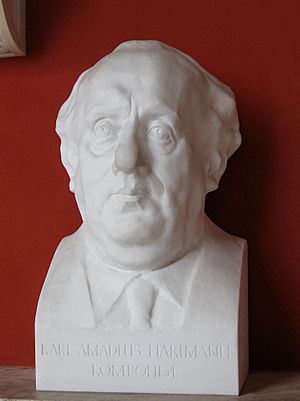

Bust of Hartmann in Munich

|

|

| Born | 2 August 1905 |

| Died | 5 December 1963 (aged 58) Munich

|

| Education | Munich Academy |

| Occupation | Classical composer |

Karl Amadeus Hartmann (born August 2, 1905 – died December 5, 1963) was a German composer. Some people think he was the greatest German composer of symphonies in the 20th century. However, he is not as well-known today, especially in countries where English is spoken.

His Life Story

Early Years and Beliefs

Karl Amadeus Hartmann was born in Munich, Germany. His father was Friedrich Richard Hartmann. Karl was the youngest of four brothers, and the older three became painters. At first, Karl wasn't sure if he wanted to be a musician or an artist.

He was greatly influenced by the events after World War I. There was a workers' revolution in Bavaria (a part of Germany) when the German empire ended. This made him an idealistic socialist, meaning he believed strongly in fairness and equality for everyone. He kept these beliefs throughout his life.

Studying Music and Facing Challenges

In the 1920s, Hartmann studied music at the Munich Academy. He learned from Joseph Haas. Later, a conductor named Hermann Scherchen greatly encouraged him. Scherchen was a supporter of the Second Viennese School, a group of composers with new ideas. Hartmann and Scherchen had a long-lasting relationship, with Scherchen guiding Hartmann.

During the time of the Nazis in Germany, Hartmann chose to stop participating in German musical life. He stayed in Germany but refused to let his music be played there. He did this because he disagreed with the Nazi government.

One of his early pieces, a symphonic poem called Miserae (written 1933–1934), was first performed in Prague in 1935. The Nazi government did not like it. This piece was dedicated to his friends who died in the Dachau Concentration Camp. He wrote, "we do not forget you."

Another work, his piano sonata 27 April 1945, shows how much the political situation affected him. It describes 20,000 prisoners from Dachau. Hartmann saw them being led away from Allied forces at the end of the war.

Learning During Wartime

Even though he was already an experienced composer during World War II, Hartmann took private lessons in Vienna. He studied with Anton Webern, who was a student of Arnold Schoenberg. Hartmann and Webern often had different personal and political ideas. However, Hartmann felt he learned a lot from Webern's careful and precise way of composing.

Rebuilding Music After the War

After Adolf Hitler's rule ended, Hartmann was one of the few important anti-fascist people in Bavaria. He had not cooperated with the Nazi government. Because of this, the Allied forces who were in charge after the war gave him a big job.

In 1945, he became a dramaturge (someone who helps choose and arrange plays or operas) at the Bavarian State Opera. He was one of the few people known internationally who had not been involved with the Nazi regime. This made him very important in rebuilding music in West Germany.

His most famous achievement was starting the Musica Viva concert series in Munich. He ran these concerts for the rest of his life. Starting in November 1945, these concerts showed German audiences music from the 20th century again. This music had been banned by the Nazis since 1933.

Hartmann also gave young composers a chance to show their music in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He helped composers like Hans Werner Henze, Luigi Nono, and Olivier Messiaen become known. He also involved artists like Jean Cocteau and Joan Miró in exhibitions at Musica Viva.

Honors and Later Life

After the war, Hartmann received many awards. These included the Munich Music Prize in 1949 and the Arnold Schönberg Medal in 1954. He became a member of the Academy of Arts in Munich and Berlin. He also received an honorary doctorate from Spokane Conservatory in Washington.

Even though he believed in socialism, he did not agree with the type of communism in the Soviet Union. In the 1950s, he refused an offer to move to East Germany.

Hartmann continued to work in Munich. His administrative duties took up a lot of his time, which meant less time for composing. In his last years, he was very ill. He died in 1963 from stomach cancer at age 58. He left his last work, a long symphonic piece called Gesangsszene, unfinished.

His Music and Style

Main Works and Revisions

Hartmann wrote many pieces, most notably eight symphonies. A symphony is a long piece of music for an orchestra. Many of his works were difficult to create and went through many changes.

For example, his Symphony No. 1, Essay for a Requiem, started in 1936 as a cantata. A cantata is a piece for singers and orchestra. This one was based on poems by Walt Whitman. It was first called Our Life: Symphonic Fragment. It was meant to show the hard times for artists and people who thought freely under the early Nazi government.

After World War II, the true victims of the Nazi regime became clear. So, the cantata's name was changed to Symphonic Fragment: Attempt at a Requiem. This was to honor the millions of people killed in the Holocaust. Hartmann revised this work in 1954–55 and published it as his Symphony No. 1 in 1956.

This shows that he was very critical of his own work. Many of his pieces were revised several times. He also held back many of his orchestral works from the late 1930s and war years. He either didn't publish them or reworked parts of them into his numbered symphonies in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Popular Pieces and Influences

Two of his most often performed symphonies are No. 4 (for strings) and No. 6. His most widely known work is probably his Concerto funebre for violin and strings. A concerto is a piece for a solo instrument and orchestra. He wrote this at the start of World War II. It uses a Hussite chorale (a type of hymn) and a Russian revolutionary song.

Hartmann tried to combine many different musical styles. These included Expressionist music (music that expresses strong emotions) and jazz sounds. He put these into traditional symphonic forms, like those used by composers such as Bruckner and Mahler. His early works were often funny or had political messages.

He admired the complex music of J.S. Bach. He also liked the deep emotional meaning in Mahler's music. He was influenced by the neoclassicism of Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith. In the 1930s, he became close with composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály in Hungary. This influenced his music too.

In the 1940s, he became interested in twelve-tone technique, a way of composing music developed by Schoenberg. Even though he studied with Webern, Hartmann's style was closer to Alban Berg. In the 1950s, Hartmann started to explore new ways of using rhythm. He often used three-part adagio (slow) movements, fugues (where different musical lines chase each other), variations, and toccatas (fast, showy pieces).

His Reputation and Legacy

How He is Remembered

After Hartmann died, not many major conductors in West Germany strongly supported his music. Hermann Scherchen, who was his biggest supporter, died in 1966. Some people think this made Hartmann's music less known in the years after his death.

However, some conductors, like Rafael Kubelik and Ferdinand Leitner, regularly performed his music. More recently, conductors like Ingo Metzmacher and Mariss Jansons have championed his works.

Hans Werner Henze, another composer, said about Hartmann's music: "Symphonic architecture was essential for him... as a suitable medium for reflecting the world as he experienced and understood it – as an agonizingly dramatic battle, as contradiction and conflict – in order to be able to achieve self-realization in its dialectic and to portray himself as a man among men, a man of this world, and not out of this world." This means that Hartmann used the structure of symphonies to show his feelings about the world and its struggles.

The English composer John McCabe wrote a piece called Variations on a Theme of Karl Amadeus Hartmann in 1964 as a tribute. It uses the beginning of Hartmann's Fourth Symphony as its main tune. Henze also made a version of Hartmann's Piano Sonata No. 2 for a full orchestra.

List of Works

Operas

- Wachsfigurenkabinett, five short operas (1929–30; three not finished)

- Des Simplicius Simplicissimus Jugend (1934–35; revised 1956–57 as Simplicius Simplicissimus)

Symphonic Works

Hartmann wrote eight symphonies. Many of his earlier symphonic works were later revised or used as parts of his numbered symphonies.

- Symphony No. 1, Versuch eines Requiems (1955)

- Symphony No. 2 (1946)

- Symphony No. 3 (1948–49)

- Symphony No. 4 for string orchestra (1947–48)

- Symphony No. 5, Symphonie concertante (1950)

- Symphony No. 6 (1951–53)

- Symphony No. 7 (1957–58)

- Symphony No. 8 (1960–62)

Concertos

- Lied for trumpet and wind instruments (1932)

- Kammerkonzert for clarinet, string quartet and string orchestra (1930–35)

- Concerto funebre for violin and string orchestra (1939, rev. 1959)

- Concerto for piano, wind instruments and percussion (1953)

- Concerto for viola, piano, wind instruments and percussion (1954–6)

Vocal Works

- Cantata (1929) for choir

- Profane Messe (1929) for choir

- Gesangsszene (1962–63) for baritone and orchestra (unfinished)

Chamber and Instrumental Works

- Piano Sonatas (No.1 in 1932, No.2 in 1945)

- String Quartets (No.1 in 1933, No.2 in 1945–6)

- Various pieces for piano, violin, and wind instruments.

See also

In Spanish: Karl Amadeus Hartmann para niños

In Spanish: Karl Amadeus Hartmann para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |