Mount Kilimanjaro facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mount Kilimanjaro |

|

|---|---|

Kilimanjaro from Amboseli National Park, Kenya

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Prominence | Ranked 4th |

| Listing |

|

| Geography | |

| Location | Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania |

| Parent range | The Eastern Rift mountains |

| Topo map | Kilimanjaro map and guide by Wielochowski |

| Geology | |

| Formed by | Volcanism along the Gregory Rift |

| Age of rock | 4 million years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | Between 150,000 and 200,000 years ago |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 6 October 1889 by Hans Meyer and Ludwig Purtscheller |

Mount Kilimanjaro is a huge, sleeping volcano in Tanzania, Africa. It's the tallest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain in the world, meaning it stands alone and isn't part of a mountain range. Its highest point is about 5,895 meters (19,341 feet) above sea level. It's also the tallest volcano in the Eastern part of the world.

For a long time, the Chagga people lived on its lower slopes. The name Kilimanjaro might mean "mountain of greatness" or "unclimbable." A German missionary, Johannes Rebmann, was the first European to report seeing this amazing mountain in 1848. Later, in 1889, Hans Meyer was the first to reach its highest peak.

Today, Kilimanjaro is part of Kilimanjaro National Park, created in 1973. It's a very popular place for hiking and climbing. There are seven main paths to reach Uhuru Peak, the mountain's highest point. Even though climbing it isn't super technical, the high altitude can make climbers sick, so it's important to go slowly.

This giant mountain was formed by volcanoes more than 2 million years ago. Its slopes are home to beautiful montane forests and cloud forests. Many unique plants and animals live only here, like the giant groundsel. Kilimanjaro also has a large ice cap and Africa's biggest glaciers. Sadly, this ice cap is shrinking very quickly, with most of it disappearing in the last century.

Contents

What's in a Name? The Story of Kilimanjaro

The name "Kilimanjaro" is a bit of a mystery! No one is completely sure where it came from or what it means.

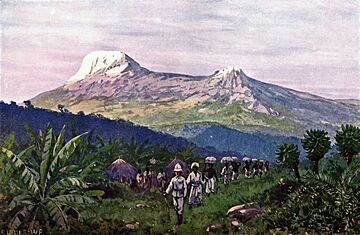

The local Chagga people have their own names for the two main peaks: Kibo and Mawenzi. Kibo means "spotted," probably because of its snowy top. Mawenzi means "broken top," which describes its jagged shape.

Some people think "Kilimanjaro" might come from a Chagga phrase meaning "unclimbable mountain." Others believe it's a mix of Swahili words. Kilima means "hill" or "mountain," and njaro could mean "greatness" or "caravans." So, it could be "Mountain of Greatness" or "Mountain of Caravans."

When the mountain was part of German East Africa in the 1880s, it was called Kilima-Ndscharo. The highest peak, Kibo, was once named after a German emperor. But after Tanzania became independent in 1964, it was renamed Uhuru Peak, which means "Freedom Peak" in Swahili.

Kilimanjaro's Volcanic Story

Kilimanjaro is actually made up of three different volcanoes! They are called Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira.

- Kibo is the tallest and is a dormant volcano, meaning it's currently sleeping but could erupt again someday.

- Mawenzi is the second highest.

- Shira is the lowest.

Both Mawenzi and Shira are extinct volcanoes, so they won't erupt anymore.

Kibo: The Highest Peak

The very top of Kilimanjaro is called Uhuru Peak. It sits on the edge of Kibo's crater. Its height is officially listed as 5,895 meters (19,341 feet). Scientists have measured it a few times, and the numbers are very close!

How the Volcanoes Formed

The Shira volcano started erupting about 2.5 million years ago. It eventually collapsed, forming a wide, flat area. Mawenzi and Kibo began erupting about 1 million years ago. They are separated by a flat area called the Saddle Plateau.

Mawenzi has a rugged, broken shape because of a lot of erosion over time. Kibo is the biggest cone and has a wide crater at its top. The last time Kibo was very active was between 150,000 and 200,000 years ago. Even today, you can still see small vents called fumaroles in its crater, releasing gas.

Kilimanjaro's Shrinking Glaciers

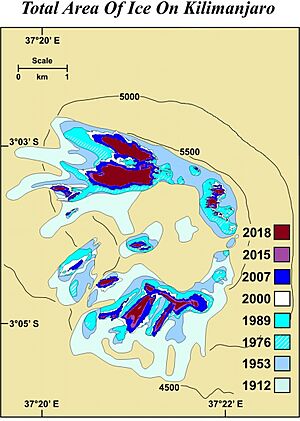

Kilimanjaro has an ice cap and glaciers at its summit because it's so tall and rises above the snow line. These glaciers are very important, but they are shrinking fast.

Scientists have studied the ice and found that the glaciers have grown and shrunk many times over thousands of years. However, the current melting is happening much faster than before.

Since the late 1880s, the ice cap has gotten much smaller. Between 1912 and 2011, almost 85 percent of the ice disappeared! This is mainly because of changes in the climate. Even though the air temperature at the top is always below freezing, sunlight hitting the vertical ice walls causes a lot of melting.

Experts believe that most of Kilimanjaro's ice will be gone by 2040. It's very unlikely any ice will remain after 2060 if the current rate of global warming continues. While the ice is beautiful, the forests lower down the mountain are actually more important for providing water to the people living nearby.

Rivers and Water

Many rivers and streams flow down Kilimanjaro, especially on the wetter southern side. These rivers are a vital source of water for the local communities.

A Special Geological Site

Kilimanjaro is recognized as one of the top 100 "geological heritage sites" in the world. This is because it's the highest stratovolcano (a cone-shaped volcano made of many layers of lava and ash) in the East African Rift that still has glaciers on its summit.

Human History and Legends

Ancient Stories of Kilimanjaro

The Chagga people, who live on the mountain's slopes, have many stories about Kilimanjaro. One legend tells of a man named Tone who angered a god, Ruwa, causing a famine. As Tone fled, the cattle he was chasing created hills, including Mawenzi and Kibo.

Another Chagga legend speaks of hidden graves of elephants filled with ivory on the mountain. It also tells of a magical cow named Rayli, whose tail glands produce special fat. If someone tries to steal it too slowly, Rayli will snort and blow them far away!

Early Mentions of the Mountain

People outside Africa might have known about Kilimanjaro a very long time ago. Ancient Greek writers like Ptolemy mentioned a "moon mountain" and a spring lake of the Nile, which could have been Kilimanjaro.

European Explorers Discover Kilimanjaro

The first Europeans known to try and reach the mountain were German missionaries Johannes Rebmann and Johann Ludwig Krapf in the mid-1800s. Rebmann was the first European to report seeing Kilimanjaro in 1848. He wrote about seeing a "beautiful white cloud" on the mountain, which he realized was snow!

Many explorers tried to climb Kilimanjaro. In 1889, German geology professor Hans Meyer and Austrian mountaineer Ludwig Purtscheller finally reached the highest summit. They were the first to confirm that Kibo has a crater at its top.

First Women Climbers

In 1909, Gertrude Benham from London tried to reach the summit. Her porters left after seeing skeletons of past climbers, but she continued alone to the edge of Kibo Crater. Bad weather forced her to turn back. The first woman to successfully reach the summit of Kilimanjaro was Sheila MacDonald, in 1927.

Modern Times and a Special Porter

The first successful climb of Mawenzi's highest summit happened in 1912.

In 1989, a special event honored the African porters and guides who helped Meyer and Purtscheller in 1889. One man, Yohani Kinyala Lauwo, was thought to be one of them. He didn't know his exact age but remembered climbing with a Dutch doctor and not wearing shoes. He passed away in 1996, 107 years after the first ascent. Some even say he was a co-first climber of Kilimanjaro!

Animals and Plants of Kilimanjaro

Animals and Their Life Cycle

You won't find many large animals high up on Kilimanjaro. But in the forests and lower areas, you might spot elephants and Cape buffaloes. Other animals include bushbucks, chameleons, dik-diks, duikers, mongooses, sunbirds, and warthogs. Sometimes, zebras, leopards, and hyenas are seen on the Shira plateau. Some animals, like the Kilimanjaro shrew and the chameleon Kinyongia tavetana, live only on this mountain!

Plant Life and Reproduction

Kilimanjaro has about 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles) of natural forests. At the very bottom, people grow crops like corn and beans. As you go higher, you'll find different types of forests:

- Montane forests with tall trees and many ferns.

- Cloud forests that are often misty and home to mosses.

- Higher up, there are Erica bushes and heathlands.

- Even higher, you'll find tough Helichrysum plants.

The types of plants on Kilimanjaro have changed over time due to climate shifts. For example, during colder, drier periods, the forests moved to lower altitudes.

Protecting Kilimanjaro

Since 1973, Mount Kilimanjaro has been a national park. This means human activities inside its borders are limited to protect its amazing plants and animals. The government has also stopped tree cutting to keep the environment healthy and save the park's unique biodiversity.

Kilimanjaro's Climate Zones

Kilimanjaro's climate changes a lot as you go up the mountain. It has two main rainy seasons, usually from March to May and around November. The southern slopes get much more rain than the northern ones.

The average temperature at the summit is about -7°C (19°F). At night, it can get as cold as -15°C to -27°C (5°F to -17°F)! Snow can fall at any time of year, but it's most common during the rainy seasons.

Climatic Zones

As you climb Kilimanjaro, you pass through five different climate zones:

- Bushland / Lower Slope: 800 to 1,800 meters (2,600 to 5,900 feet)

- Rainforest: 1,800 to 2,800 meters (5,900 to 9,200 feet)

- Heather / Moorland: 2,800 to 4,000 meters (9,200 to 13,100 feet)

- Alpine Desert: 4,000 to 5,000 meters (13,100 to 16,400 feet)

- Arctic: 5,000 to 5,895 meters (16,400 to 19,341 feet)

| Climate data for Machame 10, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (5,803 m) (2012–2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.7 (21.7) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−5.9 (21.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −9.4 (15.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

| Source: CEDA Archive | |||||||||||||

Climbing Kilimanjaro: An Adventure!

Kilimanjaro National Park makes a lot of money from tourism, which helps the local economy. In 2013, it earned US$51 million! Many people visit the park, and thousands hike the mountain each year. This creates jobs for about 11,000 guides, porters, and cooks.

Choosing Your Path to the Top

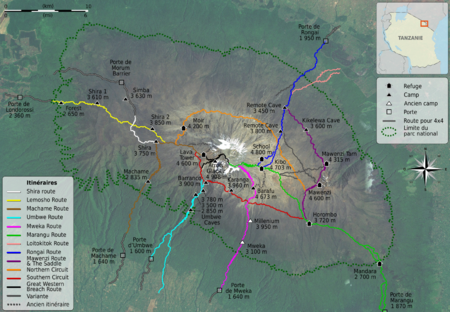

There are seven official paths to climb Kilimanjaro: Lemosho, Lemosho Western-Breach, Machame, Marangu, Mweka, Rongai, Shira, and Umbwe. Some routes, like Machame, can take six or seven days. The Rongai route is considered one of the easier camping routes. The Marangu route is also fairly easy and offers shared huts for sleeping. The Lemosho Western-Breach route is more secluded and avoids the long midnight climb to the summit.

Special Climbs on Mawenzi

If you're an experienced climber looking for a bigger challenge, you can climb the Mawenzi cone. This requires a special permit and is only for skilled climbers with the right gear.

Amazing Climbing Records

Many people have set incredible records climbing Kilimanjaro!

- The oldest person to reach the summit was Anne Lorimor, who was 89 years old in July 2019.

- The oldest man was Fred Dishelhorst, who was 88 years old in July 2017.

- Kids have also made it to the top! Maxwell J. Ojerholm reached the summit at age ten in July 2009. Keats Boyd was only 7 years old when he summited in January 2008, a record equaled by Montannah Kenney and Coaltan Tanner in 2018.

- The fastest ascent and round trip record belongs to Karl Egloff, who ran from the gate to the summit and back in just 6 hours, 42 minutes, and 24 seconds in August 2014!

- The fastest female round trip record is held by Fernanda Maciel, who completed it in 10 hours and 6 minutes.

- Even people with disabilities have climbed Kilimanjaro. Bernard Goosen, a wheelchair user, scaled it in 2007. In 2012, Kyle Maynard, who has no forearms or lower legs, crawled to the summit without help!

Staying Safe on the Mountain

Climbing Kilimanjaro is an amazing adventure, but it's important to be safe. The high altitude can cause altitude sickness, even for fit people. It's crucial to climb slowly to give your body time to get used to the height.

There are also risks like falls and rock slides. For safety, the route through the Arrow Glacier was closed in January 2024 due to unstable rocks caused by heavy rainfall. It's also very important to boil all water on the mountain to stay healthy.

Sadly, some people have died while climbing Kilimanjaro, mostly from severe altitude sickness. This shows how important it is to be prepared and listen to your guides.

Kilimanjaro in Books and Movies

Kilimanjaro is a snow-covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai 'Ngaje Ngai', the House of God. Close to the western summit there is a dried and frozen carcas of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.

Kilimanjaro has inspired many writers and filmmakers!

- It's a main setting in Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Snows of Kilimanjaro, which was also made into a movie.

- Writer Dave Eggers wrote about his climb in a short story.

- Douglas Adams, who wrote The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, even climbed the mountain in a rubber rhinoceros suit to help protect rhinos!

- The mountain is mentioned in Toto's popular 1982 song "Africa".

- An IMAX film called Kilimanjaro: To The Roof Of Africa was released in 2002.

- You can also see Kilimanjaro featured in the Lion King movies and shows.

See also

In Spanish: Kilimanjaro para niños

In Spanish: Kilimanjaro para niños