Marcher lord facts for kids

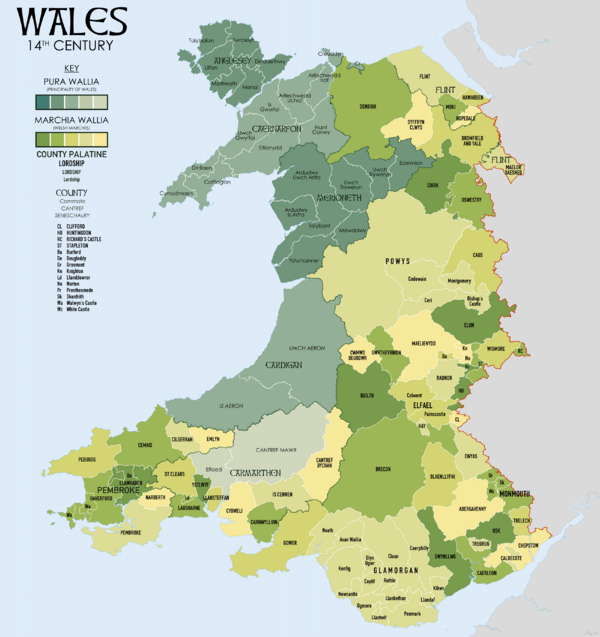

A Marcher lord (Welsh: Barwn y Mers) was a powerful noble. The King of England appointed them to protect the border between England and Wales. This border region was known as the Welsh Marches.

The word march means a border area or frontier. So, a Marcher lord was like a ruler of a borderland. They were similar to a "margrave" in other parts of Europe. But Marcher lords never held the title of "marquess" in Britain.

Some of the most famous Marcher lords were the earls of Chester, Gloucester, Hereford, Pembroke, and Shrewsbury.

Contents

The Welsh Borderlands: A Frontier Society

The Welsh Marches are famous for having many motte-and-bailey castles. These were simple castles built on mounds of earth. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, William the Conqueror wanted to control the Welsh. This process took over 200 years.

During this time, the Marches were a true frontier. It was a dangerous place, but it also offered chances for brave people. Marcher lords encouraged people to move there from all over the Angevin Empire. They also supported trade in port towns like Cardiff.

In this diverse and feudal society, Marcher barons had great power. They ruled their Norman followers like feudal lords. They also took the place of the traditional Welsh leaders, called tywysogs.

Special Powers of Marcher Lords

The Anglo-Norman lordships in the Marches were unique. Each lordship was separate and had special rights. These rights were different from regular English lordships. The King of England's laws did not always apply in the Marches.

Marcher lords ruled their lands by their own laws. They said they ruled sicut regale, which means "like a king." In England, lords were directly accountable to the king. But Marcher lords had more freedom.

They could build castles, which was a special privilege. In England, the king could easily take away this right. Marcher lords also made their own laws and even waged war. They set up market towns and kept their own records. They had their own deputies, like sheriffs.

Marcher lords could hear almost all legal cases. Only cases of high treason went to the king. They could also create forests and forest laws. They could establish towns and grant special freedoms. They could take the property of traitors and criminals. They even held their own small parliaments. However, they were not allowed to mint their own coins.

If a Marcher lord died without a legal heir, their land went back to the Crown. Welsh law was often used in the Marches instead of English law. Sometimes, there were arguments about which law should be used.

Settlement and Resistance

Feudal social structures were strong in the Marches. The region was not legally part of the Kingdom of England. Many historians believe the Norman kings simply gave these rights to the lords. However, some think these rights were more common after the Conquest. They were just suppressed in England but survived in the Marches.

Marcher lords encouraged people to settle their lands. Knights were given their own lands in exchange for military service. Towns with market privileges were also created, protected by a Norman keep. Many peasants moved to Wales. For example, King Henry I encouraged settlers from Brittany, Flemings, Normans, and England to move to South Wales.

The Plantagenet kings wanted a more centralized government. They aimed to reduce local powers. But the Marcher lords strongly resisted these changes. Records show their protests, which tell us about their special privileges.

Locally, the Marcher lords relied on their people. This allowed the people to gain specific local freedoms. One area of conflict was the churches. Lords appointed churchmen to positions, keeping tight control. This was common in Normandy. But the Welsh church, based on clan loyalties, did not like this outside control.

Over time, Marcher lords became more connected to the English kings. They received lands in England, where royal control was stricter. Many lords spent most of their time in England. It was harder for outsiders to join the established Marcher families. Hugh Le Despenser tried to do this. He traded his English lands for grants in the Welsh Marches. He even got the Isle of Lundy. When the last male heir of the de Braose family died, Despenser took their lands near Swansea. In 1321, the Marcher lords threatened civil war over this. A parliament was called to settle the issue.

Marriages Between Norman and Welsh Families

Even though there was often fighting, Norman Marcher barons and Welsh princely families often married each other. These marriages helped to create local agreements or alliances.

Families like the Mortimers, de Braoses, de Lacys, Grey de Ruthyns, Talbots, and the Le Strange families gained Welsh blood through these marriages. For example, Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Mortimer (1231–1282) was the son of Gwladys Ddu. She was the daughter of Llewelyn the Great of Gwynedd.

Matilda de Braose, a granddaughter of William de Braose, 4th Lord of Bramber, married a Welsh prince. He was Rhys Mechyll, Prince of Deheubarth. Their daughter Gwenllian married Gilbert Talbot, whose family became the earls of Shrewsbury.

The End of Marcher Powers

By the 1500s, many lordships were owned by the Crown. The Crown governed these lands using traditional methods. The Crown also directly ruled the Principality of Wales, which had its own system and was divided into counties.

The special powers of the remaining Marcher lords were unusual. These powers were officially ended by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542. These laws are also known as the Acts of Union. They organized the Marches of Wales into counties. Some lordships were added to nearby English counties. The laws also officially recognized the Council of Wales and the Marches, based at Ludlow. This council was in charge of overseeing the area.

List of Marcher Lordships

Here are some of the Marcher lordships in the Welsh Marches and the counties they became part of:

|

|

|

|

See also

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |