Margaret Fountaine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margaret Fountaine

|

|

|---|---|

Fountaine circa 1890

|

|

| Born |

Margaret Elizabeth Fountaine

16 May 1862 Norfolk, England

|

| Died | 21 April 1940 (aged 77) |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | diarist |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | lepidopterist |

Margaret Elizabeth Fountaine (born May 16, 1862 – died April 21, 1940) was a famous Victorian butterfly expert, also known as a lepidopterist. She was also a talented artist who drew nature, a diarist (someone who keeps a diary), and a world traveler. She wrote many articles for a science magazine called The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation.

Margaret Fountaine is also well-known for her personal diaries. These diaries were later turned into two popular books after she passed away. She was a skilled artist who loved and knew a lot about butterflies. She traveled all over the world, including Europe, South Africa, India, Tibet, America, Australia, and the West Indies. She wrote many papers about her work.

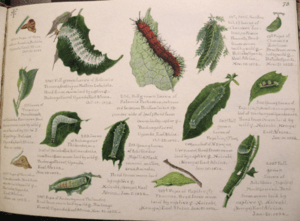

She often raised butterflies from their eggs or caterpillars. This helped her create very high-quality specimens. She collected 22,000 of these specimens, which are now kept at the Norwich Castle Museum. This collection is called the Fountaine-Neimy Collection. Her four sketchbooks, which show the life cycles of butterflies, are at the Natural History Museum in London. A group of butterflies, called Fountainea, was even named after her!

Contents

Early Life and Education

Margaret Fountaine was born in Norwich, England, on May 16, 1862. She was the oldest of seven children. Her father, Reverend John Fountaine, was a clergyman in the countryside of Norfolk. Her mother was Mary Isabella Lee. Margaret was baptized on September 30, 1862.

When her father died in 1877, her family moved to Eaton Grange in Norwich. Margaret was taught at home. On April 15, 1878, she started keeping a diary. She continued to write in her diary every day until she died in 1940.

Becoming a Butterfly Expert

Margaret Fountaine traveled the world for fifty years. She collected butterflies in sixty different countries across six continents. She became an expert in understanding the life cycles of tropical butterflies. Most of her butterfly collecting work was done by herself.

During the summers, she would return to England. There, she would organize her large collection of butterflies. Margaret also wrote reports and drew pictures of the butterflies she found. She sent these to science magazines about insects. However, many of her amazing discoveries about tropical butterflies were never fully written down.

Starting Her Scientific Journey

When Margaret was 27, she and her sisters became financially independent. They inherited a lot of money from their uncle. Margaret and her sister traveled to France and Switzerland. They used a travel guide called the Tourist Handbook.

In Switzerland, Margaret really wanted to find and collect specimens of the Scarce Swallowtail and Camberwell Beauty butterflies. She found them in the valleys. Her interest in serious entomology (the study of insects) grew stronger. She started using the scientific names for butterflies, called Linnean names, in her diary instead of just their common names.

Back in England, in the winter of 1895, she visited the home of Henry John Elwes. He was a very experienced scientific traveler. He had a huge private collection of butterflies, the biggest in the country. Margaret felt her own efforts seemed small compared to his.

First Publications and Recognition

Inspired by Elwes, Margaret traveled to Sicily with the goal of collecting insects. She was the first British butterfly collector to bravely face the bandits in southern Italy. In Sicily, she met a leading butterfly expert named Signor Enrico Ragusa. Her research in Sicily led to her first article about butterflies. It was published in The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation in 1897.

In her article, she shared new information about the local places and different types of butterflies in Sicily. Other scientists discussed her article in later issues of the magazine. In 1897, some of her butterfly specimens were accepted into the British Museum's collection. The museum only accepted specimens that were incredibly well-preserved.

After her trip to Sicily, Margaret Fountaine became a respected collector. She built professional relationships with butterfly experts at the Natural History Department of the British Museum. In 1898, she traveled to Trieste and met entomologists in Hungary, Austria, and Germany. Her second article in The Entomologist was about how species can vary.

In 1899, she went on an expedition to the French Alps. There, she met up with Elwes again. She used his reference book about European butterflies. Margaret started collecting caterpillars in the French Alps. She would raise them to become adult butterfly specimens. In her next articles for The Entomologist, she wrote about what plants butterflies eat, what plants they live on, and the best conditions to grow perfect butterfly specimens. When she returned to Britain, Elwes praised her for the excellent quality of her work and her collection. She wrote in her diary, "yet I know that if I did not turn my long days of toil to some scientific account when I got the chance, for what else have I toiled?"

Joining Scientific Societies

In 1898, Margaret was chosen to be a fellow of the Royal Entomological Society. This meant she could attend their meetings. In her diaries, she noted that she was usually the only woman there, except for one female visitor. In the summer of 1900, she and Elwes collected butterflies in Greece. They published an article about what they found in The Entomologist. She also helped Elwes with his exhibition of Greek butterflies.

The money she inherited from her uncle allowed her to travel widely and make her collection bigger. It's hard to know the exact dates of her scientific trips because she often traveled without a passport. She also didn't always write down her arrival or departure dates in her diary. However, we know about several important trips between 1901 and her death in 1940.

In 1901, she went on a trip to Syria and Palestine. This led to another article in The Entomologist. In the article, she talked about raising rare butterfly species. In Syria, she hired a guide and interpreter named Khalil Neimy, who became her travel companion. In 1903, she went to Asia Minor and returned to Constantinople with almost 1,000 butterflies. Her articles about this trip discussed how seasons and geography affected butterfly species. This led to many notes and letters about the topic in later issues of the magazine.

Documenting Butterfly Life Cycles

In 1904 and 1905, she went on scientific trips to South Africa and Rhodesia. There, she created sketchbooks with drawings and notes to document butterfly eggs, caterpillars, and chrysalises. Norman Denbigh Riley, who later became the head of the Entomology Department at the British Museum, said that "these sketchbooks were most beautifully done and illustrated the metamorphosis of many species which had not been previously known to science." Metamorphosis is the process where an insect changes completely from one form to another, like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly.

Her research on butterfly life cycles, the plants they eat, and how their skin and color changed with the seasons was published in Transactions of the Entomological Society. This highly scientific article was reviewed and praised by other butterfly experts. When she was back in London, Margaret prepared her African specimens. After that, she went on trips to the United States, Central America, and the Caribbean. In Kingston, Jamaica, she gave a talk at the Kingston Naturalists' Club about "The cleverness of caterpillars."

Historically, scientific societies in Britain did not allow women to join. But in the first half of the 19th century, societies like the Royal Entomological Society, the Botanical Society of London, and the Zoological Society started to admit women. When Margaret Fountaine attended the Second International Congress of Entomology in Oxford in 1912, she was invited to formally join the Linnean Society. This was a major achievement in her career as a butterfly expert. Fifteen years earlier, Beatrix Potter (the author of Peter Rabbit) could not even attend a reading of her own scientific paper at the society because she was a woman.

Before World War I, Margaret Fountaine went on a trip to India, Ceylon, Nepal, and Tibet. On this trip, she painted watercolors of caterpillars and butterflies, which were published in The Entomologist. During the war, Fountaine traveled to the US. In 1917, she published articles about her collection while volunteering for the Red Cross. In 1918, she ran out of money because she couldn't get her funds sent to the USA. So, she took paid work preparing specimens for the Ward's Natural Science Establishment.

After the war, Margaret Fountaine's last major butterfly trip was to Khalil in the Philippines. A report about this trip was published in The Entomologist. Fifty years later, this report was used as a reference for conservation work.

Margaret Fountaine was in her mid-sixties, but she kept traveling for expeditions. However, she focused more on her watercolors and collecting. She only published occasional notes about her trips in The Entomologist. She traveled to West and East Africa, Indo-China, Hong Kong, the Malay States, Brazil, the West Indies, and Trinidad. Her letters show she was always looking for rare specimens.

At 77 years old, she had a heart attack in Trinidad. She was reportedly found dead on a path on Mount St. Benedict, with a butterfly net in her hand. The monk who found her, Brother Bruno, brought her body back to Pax Guest House, where she was staying. She was buried in an unmarked grave at Woodbrook Cemetery in Port of Spain, Trinidad.

Margaret Fountaine became widely famous after her death, when her collection and diaries were finally revealed. Her amazing talent for drawing butterflies scientifically and artistically became more widely known. She left a large collection of scientifically accurate watercolors to the British Museum of Natural History.

Butterfly Collection and Diaries

Margaret Fountaine's huge butterfly collection was only opened 38 years after she died. According to her will, it had been placed at the Norwich Castle Museum in the year she died. She had also stated that the collection should only be opened in 1978. It contained a box and ten display cases with more than 22,000 butterfly specimens.

Her Diaries

In the box that was opened along with her butterfly collection were Margaret Fountaine's diaries. She had filled twelve large, cloth-bound books with about 3,203 pages and over a million words. These diaries showed a mix of Victorian privacy and surprising openness.

The diaries were edited by W. F. Cater, who worked for the Sunday Times. He turned them into two books for the general public. Cater made a shorter, 340-page version of her diaries. He focused on parts about travel, while not giving much attention to her scientific work of collecting, breeding, and preparing specimens.

Dr. Tony Irwin, a former curator at the Norwich Castle Museum, announced the existence of the diaries. He emphasized Margaret's personal life more than her scientific contributions. He thought her butterfly collection was "not outstanding." However, Margaret Fountaine's work as an entomologist was actually quite typical for amateur women scientists during the Victorian era.

During Margaret's lifetime, entomology (the study of insects) was very popular among wealthy people in Britain. Natural history societies had many members. Scientific books were no longer written only by top scientists. For example, Emma Hutchinson's 1879 book, "Entomology and Botany as Pursuits for Ladies," encouraged women to study butterflies, not just collect them. Natural history was especially popular among women in the Victorian era.

A review of The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation shows that women contributed articles to almost every edition. However, Margaret Fountaine's membership in important scientific societies was groundbreaking. In 1910, the Royal Entomological Society had only six female fellows.

Legacy and Namesakes

In 1971, A. H. B. Rydon named the butterfly group Fountainea in Margaret Fountaine's honor. Kenneth J. Morton also named a type of dragonfly, Ischnura fountainei, after her. This was because she collected the very first specimen of that species.

Margaret Fountaine's drawings of African plants and animals were shown in the 2019 Natural History Museum exhibition called Expeditions and Endeavours. Her illustrations were also featured in the Natural History Museum's 2014 book, Women Artists: Images of Nature by Andrea Hart.

See also

In Spanish: Margaret Fountaine para niños

In Spanish: Margaret Fountaine para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |