Montreal campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Montreal campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |||||||

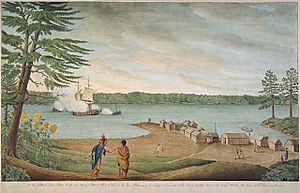

Surrender of the French Army in Montreal in 1760 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11,000 regulars, 6,500 provincials, 700 Iroquois |

3,200 regulars and Marines, Unknown militia, unknown natives |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | 2,200 surrendered, 1,000 sick or missing. Militia and natives pacified |

||||||

The Montreal campaign, also called the fall of Montreal, was a big attack by the British army. It happened from July 2 to September 8, 1760. This event was part of the French and Indian War, which was itself a part of the larger Seven Years' War happening around the world.

The British army, led by General Jeffery Amherst, was much larger than the French forces. They surrounded and captured Montreal, which was the last major French city in French Canada.

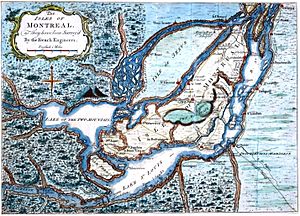

About 18,000 British soldiers moved towards Montreal from three different directions. General Amherst led one group from Lake Ontario. Another group, led by James Murray, came from Québec. The third group, under William Haviland, advanced from Fort Crown Point.

As the British moved, they captured French outposts. Many Canadiens (French settlers in Canada) either left the French army or gave up their weapons. The Native American allies of the French also started making peace deals with the British.

The French military leader, François Gaston de Lévis, wanted to fight to the very end in Montreal. However, Pierre de Rigaud, the Governor of French Canada, convinced him to surrender. Lévis tried to get special terms for his soldiers, but the British refused. So, the French had to surrender completely on September 8. This surrender meant that the British had fully taken over New France.

Contents

Why the Montreal Campaign Happened

After the fall of Quebec City in 1759, French forces moved west. During the winter, British forces led by James Murray held Quebec. They had to wait for spring 1760 for more soldiers and supplies to arrive by ship.

In April, the French commander Lévis tried to take back Quebec with a surprise attack. He won the Battle of Sainte-Foy and then surrounded the city. They waited for French ships to bring help. But British ships arrived first on May 15, helping the Quebec defenders. This forced Lévis to stop his attack and retreat.

After this defeat, Lévis went to Montreal to talk with Governor Vaudreuil about what to do next. Both leaders tried their best to defend their colony, even though things looked bad. Lévis had hoped for help from a French fleet that had sailed from France. But he soon learned that British ships had stopped this fleet. Many French ships were captured, and about 500 soldiers were lost. A few French ships did make it to the Saint Lawrence River, but they were trapped by the British navy. These trapped ships were later defeated in the Battle of Restigouche in July.

British commanders wanted to finish the war quickly. With more soldiers in Quebec, the city became a starting point for taking the rest of French Canada. The British planned to capture Montreal, which was the last major French stronghold. General Jeffery Amherst, the overall commander, gathered his large army for a final victory at Montreal.

Preparing for the Attack

During the winter of 1759–1760, a British force moved from Albany to Lake Ontario. They joined up with William Johnson's group, which had captured Fort Niagara the year before. They set up a base at Oswego on Lake Ontario. They also built a small fleet of ships and gunboats to carry soldiers down the Saint Lawrence River to Montreal.

Three main British forces were planned:

- Amherst's group: Over 10,000 men, including about 4,000 regular soldiers. They would move east from Lake Ontario along the Saint Lawrence River. This was the longest and hardest route because of dangerous rapids.

- William Haviland's group: 3,500 men, including famous Rogers' Rangers. They would come from New York through Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. This path was expected to have strong French defenses.

- James Murray's group: 4,000 men. They would advance from Quebec west along the Saint Lawrence. They would approach Montreal from the east.

All three groups would meet at Montreal in a "pincer movement" (like pincers closing) before winter. In total, Amherst had about 18,000 men. About 11,000 were regular soldiers, and over 6,500 were provincial soldiers from different colonies. There were also more than 700 Iroquois warriors.

Amherst sent Robert Rogers and his Rangers on a mission to attack French supplies. This raid, which started on June 3, lasted almost three weeks. Rogers found that the French forts were too strong to attack directly. But his men surprised and burned the main supply depot at Sainte-Thérèse. On their way back, the British fought off French ambushes. This raid was a big success for the British. They captured over 100 French soldiers and gained important information about French defenses. The raid also made some French militia leave and many Native allies abandon the French cause.

Lévis used all his available soldiers to defend Montreal. He had about 3,200 regular soldiers. He couldn't rely much on his French-allied Native Americans because many were leaving. There were also many Canadian civilians who could fight, but most were tired of the war and ready to surrender. Lévis ordered Captain Pierre Pouchot to slow down Amherst's army at Fort Lévis. Pouchot had 340 soldiers and militia there. Another French force was ready to defend the rapids above Montreal. The main French forts blocking Haviland's path were Forts Chambly, Saint-Jean, and Île aux Noix. These were reinforced with about 3,000 soldiers. To stop Murray, Lévis ordered Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas to watch the Saint Lawrence River with 1,800 men and small armed ships.

The Campaign Begins

Murray's Journey

James Murray's group of 4,000 men left Quebec first on July 13. Half of them marched along the riverbank, while the rest traveled on ships and boats. These boats carried heavy cannons and supplies for a possible long siege. Murray's journey went through the most populated areas of French Canadians. So, he had to try and make the people peaceful.

As Murray's ships slowly moved upriver, French soldiers tried to bother them, but they didn't stop the advance. Murray's ships fought French defenses at Deschambault and then captured Grondines. The Canadian people there swore loyalty to the British and gave up their weapons. Murray continued to Sainte-Croix and further, successfully making the French Canadians loyal to King George II. This worked well because Murray could speak French. He also helped the struggling economy by giving out gold and silver coins. The French military had spread false stories that the British would be cruel. But this actually worked against the French, as they were the ones threatening people if they didn't resist the British.

Murray reached the French defenses at Trois-Rivières by mid-August. He managed to go around them, which frustrated the French commander Dumas. Murray's Rangers found French soldiers dug in near Sorel on August 21. Murray attacked them in the dark. The French were scattered, and the town was burned. But despite this, the Canadians gave up their weapons and stopped supporting the French.

By August 26, Murray's force was less than 10 kilometers from Montreal. Eight Native American chiefs, including the Huron, wanted to make peace with Great Britain. Murray couldn't sign a formal treaty, but he discussed their rights and gave them a pass to protect them.

The last strong French defense was at Varennes. Murray sent a group of Rangers and soldiers ahead on August 31. A French unit of 60 soldiers and 320 militia fired at them, but the British pushed them back. After a short fight, the town was secured. The British had very few losses, while the French had some killed or wounded and 40 taken prisoner. Varennes was then looted and burned by British troops, but it still surrendered to Murray. Lévis ordered his troops to fall back to Montreal. Over the next few days, Murray's soldiers moved closer to Montreal. About 4,000 Canadians were disarmed and swore loyalty to the British King. Murray's group then waited for Haviland and Amherst to arrive. Murray had done a great job. He disarmed the local people and caused thousands of Canadian militiamen to leave the French army.

Amherst's Journey

Amherst's force left Oswego on August 10. With them were William Johnson and George Croghan, along with 700 Native Americans. Captain Joshua Loring, commanding two British ships, went ahead to bombard Fort Lévis. Guns were also placed on nearby islands to fire at the fort. They captured a French ship called l'Outaouaise, which they then used against the French. For three days, both sides fired at each other. By August 24, the French commander Pouchot ran out of ammunition and surrendered to Amherst. Most of the Native Americans with Amherst wanted to loot Fort Lévis, but Amherst refused. Many of them went home, leaving about 170 to continue.

Meanwhile, Johnson and Croghan were very important in convincing the French-allied Native Americans to switch sides. Representatives from different tribes came to talk with Johnson. Even though Amherst was sometimes rude to the Native Americans, they agreed to a treaty with Johnson. They promised to stay neutral in return for future friendship. Lévis tried to get help from his Native allies at a meeting, but the Native Americans left. About 800 French-allied warriors were disarmed by Johnson. Even better, about a hundred of them joined the British and helped capture French prisoners for information.

On August 31, Amherst left Fort Lévis, which he renamed Fort William Augustus. He moved downstream on the Saint Lawrence River. With the Native Americans no longer a threat, Amherst's only worry was the dangerous rapids on the Saint Lawrence. The ships had to go in a single line. They passed several rapids with few losses. At the same time, the French commander La Corne told Lévis that Fort Lévis had been taken and Amherst was only a day away from Montreal.

On September 4, the ships reached the most dangerous part of the river, the Lachine rapids. The journey was very risky, even with Mohawk river guides. Many boats were wrecked, overturned, or crashed. Many men were swept away and drowned. However, they soon reached Lake Saint-Louis and landed at Île Perrot, about 35 kilometers from Montreal. It had been costly: 46 boats were totally destroyed, and 84 men drowned. La Corne couldn't defend the area, so Lévis ordered all French troops west of Montreal to retreat to the Island of Montreal.

Amherst spent the next day repairing his boats. A day later, British troops got back on their boats. French scouts watching Amherst's force retreated to Lachine, 11 kilometers from Montreal. Amherst's advanced troops followed them closely.

Haviland's Journey

A day after Amherst started, William Haviland's force of 3,500 men left Crown Point. They moved along the Richelieu River. Blocking their way was Île aux Noix, a French position commanded by Louis de Bougainville. The British landed 2 kilometers upstream from the island. They tried to get to the east side of the island. This area was defended by the few remaining French warships and several gunboats. The island also had many forts, and French troops had been sent to reinforce Bougainville.

On August 23, British cannons began firing at the forts on Île aux Noix. Meanwhile, Haviland sent Colonel John Darby's light infantry, Rogers' Rangers, and some Native Americans. They dragged three cannons through the forest and swamps to the back of Bougainville's position. The French didn't expect this, thinking it was impossible. But within a few days, the cannons and soldiers made it through without being seen. They set up the cannons on the riverbank where the French ships were defending. Rogers' cannons opened fire on these ships. The closest ship was hit, and its captain and some crew were killed or wounded. The rest of the crew abandoned the ship, and the wind blew it ashore, where the British captured it. The other French ships tried to escape but got stuck in a bend in the river. The Rangers swam out and captured them. With the French ships gone, the British could move their boats into the South channel.

The next day, rumors of a French retreat led the Rangers and regular soldiers to attack the fort. They captured it along with 50 French prisoners. The British had very few losses, while the French had 80 killed, wounded, or drowned. Bougainville, following orders, left the island and headed for Fort Saint-Jean. With all their ships captured, French river communication was cut off. Haviland's force then crossed the river to take Fort Saint-Jean on August 29. The French decided to abandon this fort too, setting it on fire before leaving for Fort Chambly, their last stronghold on the river. Rogers' Rangers found the burning ruins of Fort Saint-Jean the next day. They moved along the road to Montreal and captured 17 French soldiers who were left behind.

A group of 1,000 men from Haviland's force, including siege cannons, joined Rogers the next day. They arrived at Fort Chambly. The 70-year-old French commander refused to surrender at first. But after a 20-minute bombardment from British cannons, he surrendered with 71 men. Bougainville ordered all French forces to go to Montreal. But by now, many French soldiers were leaving the army. With the forts and towns in the Richelieu Valley now in British hands, Haviland's forces rested for two days before marching on Montreal.

Montreal Under Siege

At 11 AM on September 6, Amherst's army landed without resistance at Lachine. They then marched towards Montreal. The French army retreated inside the city walls. As Amherst approached, almost all Canadian militia had left. The remaining French force in Montreal was less than 2,200 regular soldiers and about 200 marines. Many of these had also deserted, and the rest were so tired that their officers had to beg them rather than command them. About 241 men were also too sick or wounded to fight.

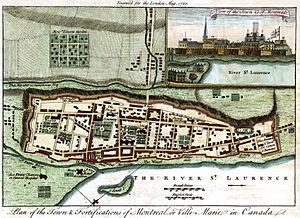

Montreal was a long, narrow city with wooden or stone houses. It had three churches and four convents. At one end, there was a high mound of earth with a small fort and a few cannons. The whole city was surrounded by a shallow ditch and a stone wall. This wall was built to defend against Native American attacks, not against powerful cannons.

The next day, Amherst set up his camp on the eastern side of the city. His main British army began bringing up their siege cannons from Lachine. At 10 AM, Murray's army landed at Pointe-aux-Trembles and marched to Longue-Pointe, setting up camp below Amherst's force. Governor Vaudreuil, looking across the Saint Lawrence, could see the British tents on the southern shore. The people of Montreal refused to fight. A group of French marines was still on Saint Helen's Island. The small French navy only had one small ship and two half-galleys. The rest of the French army was placed along Montreal's walls. Later that day, Haviland arrived on the southern shore, joining Amherst's camp. This completed the circle around the city. All three British armies had arrived at Montreal from different directions, almost at the same time.

The city was also crowded with people who had fled their homes. Vaudreuil called a meeting of his officers that same day. They decided that since most of the militia and many regular soldiers had left, and the Native American allies had joined the British, further fighting was impossible. Lévis sent his second-in-command to ask for a one-month ceasefire. This request was refused. Amherst gave the French six hours to make their final decision. Vaudreuil then presented a long document with 55 articles (rules) for surrender. The officers all agreed to these terms.

The Surrender of Montreal

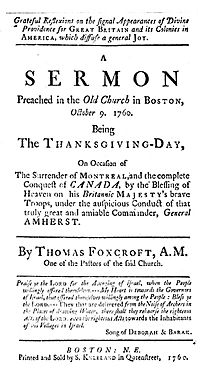

At 10 AM on September 7, Bougainville took the surrender terms to Amherst's tent. Amherst agreed to most of them, changed some, and completely refused others. The French officers thought the most important part was that their troops should march out with their weapons and cannons, with "honors of war." But Amherst replied: "The whole garrison of Montréal and all other French troops in Canada must lay down their arms, and shall not serve during the present war."

This demand felt unacceptable to the French. So Vaudreuil sent Bougainville back to argue. But Amherst would not change his mind. Then Lévis tried to convince him, sending an officer with a note saying they could not agree to such harsh terms. Amherst answered that he was firm because of the "infamous part" French troops had played in encouraging Native Americans to commit "horrid barbarities" during the war. He refused to change the conditions. Despite Lévis's strong protests, the surrender had to be signed.

The surrender finally happened the next day at 8 AM. Amherst signed it in a house just northwest of Montreal's walls. With this surrender, Canada and all its lands became part of the British Empire. French officers, soldiers, and sailors were to be sent back to France on British ships. The people of the colony were allowed to practice their religion freely. Religious groups could keep their property and rights. Anyone who wanted to move to France could do so. Canadians were allowed to keep their property, including their slaves.

In the evening, Murray's soldiers moved into the suburbs. Lévis ordered his battalions to burn their flags. The next morning, a British group of soldiers and artillery, led by Colonel Frederick Haldimand, entered Montreal. They took positions in the main square. One by one, the French battalions, totaling 2,200 fit men, laid down their weapons. The British then took control of all posts within Montreal. The next day, the flags of two British regiments lost in 1756 were found. They were marched out of Montreal in a procession. Later that day, General Amherst issued orders, which were the first official documents from Great Britain after the complete capture of Canada.

What Happened Next

The victory at Montreal was the final step in the British taking over Canada. The British had effectively won the war in North America. Amherst had thought about attacking the French in Louisiana, but he decided against it. The last important campaign was the British advance to Michigan at Fort Detroit in November. Rogers' Rangers captured this fort. They took a warship, 33 cannons, many supplies, and 2,500 soldiers.

Amherst gave silver medals to the Native Americans who had helped him at Montreal. With the French defeated, their Native American allies made a peace treaty with the British in October. This treaty allowed Native Americans to travel freely between Canada and New York. This was important for their fur trade between Montreal and Albany.

Throughout October, French prisoners were sent to Quebec and then transported to France on British ships. At the same time, British provincial soldiers were sent home. Plans were made to keep British soldiers in Montreal for the winter. By October 22, all French soldiers had left, except for a few who wanted to stay and swore loyalty to the British King. Lévis returned to France in December.

The news of Montreal's capture was met with great happiness in Great Britain. The London Magazine in 1760 even published a song about it, praising Amherst as a hero. This success was used as propaganda. An artist named Francis Hayman was asked to create artworks about it. His painting "The Surrender of Montreal" was shown in 1761 with the words: "Power exerted, conquest obtained, mercy shown."

The Anglo-Cherokee War ended the following year with a treaty. The details of the British takeover of Canada still needed to be worked out between England and France. The British offered fair terms to the French Canadians. These terms later became law in the Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act. Britain promised the 60,000 to 70,000 French-speaking people that they would not be forced to leave. They could keep their property, practice their religion freely, and move to France if they wished. They also got equal treatment in the fur trade.

With the war in North America mostly over, the fighting moved to the Caribbean the next year. Spain joined the war on France's side but was quickly defeated. They lost Havana and Manila to British forces. The war in Europe also went badly for France and its allies.

The loss of Montreal was a huge blow to France's hopes of getting Canada back in future peace talks. The French government had thought that if they could hold onto some land in Canada, they could trade it for land captured by French troops in Europe. But this became harder for France when the British captured French Caribbean islands like Martinique and Dominica. By the end of the war, everyone agreed that New France would be given to the British. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 officially recognized that Canada now belonged to Great Britain.

Thomas Gage was appointed the first British Governor of Montreal. He and other British officials kept much of the previous French system of government.

Images for kids

-

Surrender of Montreal to General Amherst by Francis Hayman.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |