Nikolay Bogolyubov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nikolay Bogolyubov

|

|

|---|---|

| Николай Боголюбов, Микола Боголюбов | |

|

|

| Born | 21 August 1909 |

| Died | 13 February 1992 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | Soviet, Ukrainian, Russian |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | Stalin Prize (1947, 1953) USSR State Prize (1984) Lenin Prize (1958) Heineman Prize (1966) Hero of Socialist Labor (1969, 1979) Max Planck Medal (1973) Lomonosov Gold Medal (1985) Dirac Prize (1992) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics, mathematical physics, mathematics |

| Institutions | Kyiv University Steklov Institute of Mathematics Lomonosov Moscow State University Joint Institute for Nuclear Research |

| Doctoral advisor | Nikolay Krylov |

| Doctoral students | Dmitry Zubarev Yurii Mitropolskiy Sergei Tyablikov Dmitry Shirkov |

Nikolay Nikolayevich Bogolyubov (Russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Боголю́бов; Ukrainian: Микола Миколайович Боголюбов, romanized: Mykola Mykolaiovych Bogoliubov; 21 August 1909 – 13 February 1992) was a very important Soviet, Ukrainian, and Russian mathematician and theoretical physicist. He made huge contributions to many areas of science. These include quantum field theory, which studies the smallest particles, and statistical mechanics, which looks at how many particles behave together. He also worked on dynamical systems, which are systems that change over time. He received the Dirac Medal in 1992 for his amazing work.

Contents

- Biography

- Early Life and Education (1909–1921)

- Kyiv Period: A Young Genius (1921-1940)

- Working During World War II (1941–1943)

- Moscow: New Discoveries (1943–?)

- Steklov Institute and Quantum Physics (1947–?)

- Dubna: Leading a Research Center (1956–1992)

- Work in Ukraine After the War

- Family Life

- Teaching and Students

- Awards and Recognition

- Research and Contributions

- Images for kids

- See also

Biography

Early Life and Education (1909–1921)

Nikolay Bogolyubov was born on August 21, 1909, in Nizhny Novgorod, which was part of the Russian Empire. His father, Nikolay Mikhaylovich Bogolyubov, was a priest and a teacher of theology and philosophy. His mother, Olga Nikolayevna Bogolyubova, was a music teacher.

When Nikolay was six months old, his family moved to Nizhyn, a city in Ukraine. They later moved to Kyiv in 1913. Nikolay was mostly taught at home by his father. He learned basic math and several languages like German, French, and English.

During the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921), his family moved to a village called Velyka Krucha. Nikolay attended the Velykokruchanska seven-year school from 1919 to 1921. This was the only school he officially graduated from.

Kyiv Period: A Young Genius (1921-1940)

In 1921, Nikolay's family moved back to Kyiv. Even though they were poor, Nikolay continued to study physics and mathematics on his own. By the age of 14, he was already taking part in a special seminar at Kyiv University. This seminar was led by a famous mathematician, Academician Dmitry Grave.

In 1924, when he was just 15, Nikolay Bogolyubov published his first scientific paper. A year later, he joined a Ph.D. program at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. His supervisor was the well-known mathematician Nikolay Krylov.

Nikolay earned his first advanced degree, called Kandidat Nauk (similar to a Ph.D.), in 1928 at the age of 19. His doctoral paper was about "direct methods of variational calculus." Just two years later, in 1930, he earned the highest degree in the Soviet Union, called Doktor Nauk (similar to a Habilitation). This degree showed he had made a very important contribution to his field.

During these early years, Bogolyubov worked on many math problems. These included calculus of variations, almost periodic functions, and dynamical systems. His work quickly gained him recognition. He even won a prize from the Bologna Academy of Sciences in 1930.

From 1931, Bogolyubov and Krylov worked together on problems related to nonlinear mechanics and nonlinear oscillations. They became leaders of the "Kyiv school of nonlinear oscillation research." Their work led to a new field of study called non-linear mechanics.

In 1936, Nikolay Bogolyubov became a professor. From 1936 to 1940, he led the Department of Mathematical Physics at Kyiv University. In 1939, he was chosen as a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

Working During World War II (1941–1943)

When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, many universities and institutes were moved to safer areas. Nikolay Bogolyubov moved to Ufa. There, he became the head of math departments at two universities from July 1941 to August 1943.

Moscow: New Discoveries (1943–?)

In the fall of 1943, Bogolyubov moved to Moscow. He joined the Department of Theoretical Physics at Moscow State University (MSU).

During 1943-1946, Bogolyubov studied stochastic processes, which are processes that involve randomness. He showed that how a system behaves can depend on the time scale you look at it. This idea became very important in understanding how systems change over time in statistical physics.

In 1945, he proved a key theorem about non-linear differential equations. This work helped create a new method in non-linear mechanics. In 1946, he published important works on statistical mechanics. These ideas were put into his book, Problems of dynamical theory in statistical physics.

In 1953, Nikolay Bogolyubov became the Head of the Department of Theoretical Physics at MSU.

Steklov Institute and Quantum Physics (1947–?)

In 1947, Nikolay Bogolyubov started and led the Department of Theoretical Physics at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics. At this institute, Bogolyubov and his team made many important contributions. These included work on renormalization theory and quantum field theory.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Bogolyubov worked on the theories of superfluidity and superconductivity. These are amazing states of matter where fluids flow without resistance or materials conduct electricity perfectly. He developed the BBGKY hierarchy method to understand these phenomena. He also created a theory for superfluidity and made other key discoveries.

Later, he focused on quantum field theory. He introduced the Bogoliubov transformation and proved important theorems like the Bogoliubov's edge-of-the-wedge theorem and the Bogoliubov–Parasyuk theorem. In the 1960s, he became interested in the quark model of hadrons. In 1965, he was one of the first scientists to study the new quantum number called color charge.

In 1946, Nikolay Bogolyubov became a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. He became a full member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR and the USSR in 1953.

Dubna: Leading a Research Center (1956–1992)

From 1956, Nikolay Bogolyubov worked at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia. He helped start and became the first director of the Laboratory of Theoretical Physics there. This lab became a famous place for research in quantum field theory, nuclear physics, and statistical physics. Nikolay Bogolyubov was the Director of JINR from 1966 to 1988.

Work in Ukraine After the War

After World War II, Nikolay Bogolyubov continued to work in Ukraine. He was the dean of the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics at Kyiv University. He also led the Department of Probability Theory at the Institute of Mathematics of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

In the early 1960s, Bogolyubov helped create the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Kyiv. He served as its director from 1966 to 1973.

Family Life

Nikolay Bogolyubov married Evgenia Pirashkova in 1937. They had two sons, Pavel and Nikolay Jr. Both of his sons also became theoretical physicists. Nikolay Jr. works in mathematical physics and statistical mechanics. Pavel was a senior researcher at the Laboratory of Theoretical Physics at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research.

Teaching and Students

Nikolay Bogolyubov was a mentor to many students. Some of his notable students include Yurii Mitropolskiy, Dmitry Shirkov, and Dmitry Zubarev. He was known for his kind and polite teaching style, which is often called the "Bogolyubov approach" in Russia.

Awards and Recognition

Nikolay Bogolyubov received many high honors and awards from the USSR and other countries.

- Major Awards

- Two Stalin Prizes (1947, 1953)

- USSR State Prize (1984)

- Lenin Prize (1958)

- Hero of Socialist Labour, twice (1969, 1979) - This is a very high honor for work achievements.

- Six Orders of Lenin

- Heineman Prize for Mathematical Physics (USA, 1966)

- Max Planck Medal (Germany, 1973)

- Lomonosov Gold Medal (1985) - For outstanding work in mathematics and theoretical physics.

- Dirac Medal (1992, given after his death)

- Academic Recognition

He was an honorary member of many important academies around the world. These included the National Academy of Sciences (United States), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Polish Academy of Sciences. He also received honorary doctorates from many universities, including the University of Chicago and the University of Berlin.

- Memory

Several institutions and places are named in his honor:

- N.N. Bogolyubov Institute for Theoretical Problems of Microphysics (Moscow State University)

- Bogoliubov Institute of Theoretical Physics National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine)

- Bogoliubov Laboratory of Theoretical Physics (Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna)

- Bogolyubov Prize and Bogolyubov Prize for young scientists (Joint Institute for Nuclear Research)

- Bogolyubov Prize (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

- Bogolyubov prospect (Russian: проспект Боголюбова), a central street in Dubna.

Research and Contributions

Nikolay Bogolyubov's main work focused on nonlinear mechanics, quantum field theory, and statistical mechanics. He also worked on variational calculus and mathematical physics.

Mathematics and Non-Linear Mechanics

- From 1932 to 1943, he worked with Nikolay Krylov. They developed mathematical methods to solve non-linear differential equations. These equations are used to describe systems that don't change in a simple, straight line.

- In 1937, they proved the Krylov–Bogolyubov theorems.

- In 1956, he proved the edge-of-the-wedge theorem. This theorem is important for understanding how particles behave in physics.

Statistical Mechanics

- In 1939, with Nikolay Krylov, he showed how to get the Fokker–Planck equation. This equation describes how systems change over time due to random forces.

- In 1945, he introduced the idea of a "hierarchy of relaxation times." This concept is very important for understanding how systems reach balance in statistical physics.

- In 1946, he created a general method to understand how kinetic equations work for classical systems. This method uses a set of equations now known as the Bogoliubov–Born–Green–Kirkwood–Yvon hierarchy.

- In 1947, he extended this method to quantum systems.

- From 1947 to 1948, he studied superfluidity. He calculated the energy spectrum for a gas of particles called a Bose gas. He showed that this spectrum was similar to Helium II, which is a superfluid.

- In 1958, he developed a theory for superconductivity. He showed how it was similar to superfluidity.

Quantum Theory

- In 1955, he developed a theory for the scattering matrix (S-matrix) in quantum field theory. This matrix describes how particles interact and scatter off each other.

- In 1955, with Dmitry Shirkov, he developed the renormalization group method. This method helps scientists deal with infinities that appear in quantum field theories.

- Also in 1955, with Ostap Parasyuk, he proved the Bogoliubov-Parasyuk theorem. This theorem showed that the scattering matrix is finite and unique for certain theories.

- In 1965, with Boris Struminsky and Albert Tavkhelidze, he suggested a quark model. They introduced a new property for quarks called color charge.

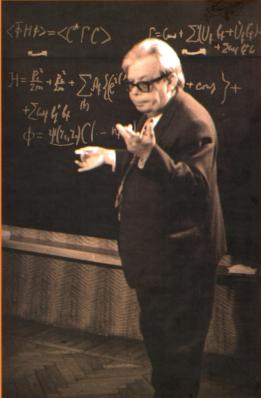

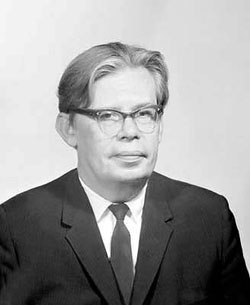

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nikolái Bogoliúbov para niños

In Spanish: Nikolái Bogoliúbov para niños

- Bogoliubov approximation

- Bogolyubov-Born-Green-Kirkwood-Yvon hierarchy

- Bogoliubov causality condition

- Bogolyubov's edge-of-the-wedge theorem

- Bogolyubov inequality

- Bogoliubov inner product

- Bogolyubov's lemma

- Bogoliubov-Parasyuk theorem

- Bogoliubov quasiparticle

- Bogoliubov transformation

- Describing function method

- Goldstone boson

- Krylov-Bogoliubov averaging method

- Krylov-Bogolyubov theorem

- Landau pole

- Peierls–Bogoliubov inequality

- Quantum triviality