Norman Borlaug facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Norman Borlaug

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

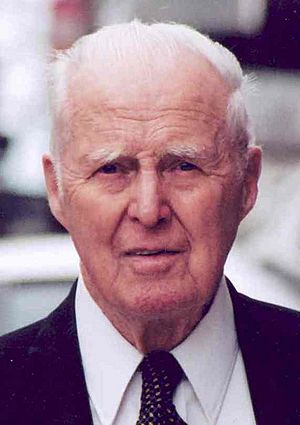

| Born | March 25, 1914 Cresco, Iowa, United States

|

| Died | September 12, 2009 (aged 95) Dallas, Texas, United States

|

| Alma mater | University of Minnesota (B.S., M.S., Ph.D) |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Variation and Variability in Fusarium lini. (1942) |

| Doctoral advisor | Jonas Jergon Christensen |

| Other academic advisors | Elvin C. Stakman |

Norman Ernest Borlaug (March 25, 1914 – September 12, 2009) was an American scientist who helped feed billions of people around the world. He was an agronomist, which means he studied how to grow crops better. Borlaug led efforts that greatly increased how much food farmers could grow, a time known as the Green Revolution.

Because of his amazing work, Borlaug received many important awards. These included the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Borlaug earned his first degree in forestry in 1937. He then got his Ph.D. in plant pathology (the study of plant diseases) and genetics from the University of Minnesota in 1942. He later worked in Mexico for an organization called CIMMYT. There, he created new types of wheat that were shorter, produced more grain, and could fight off diseases.

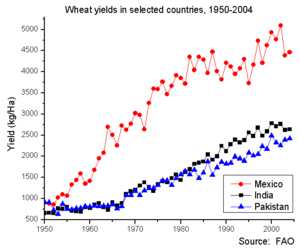

In the middle of the 20th century, Borlaug helped bring these new, high-yielding wheat types and modern farming methods to Mexico, Pakistan, and India. Because of his work, Mexico started exporting wheat by 1963. Between 1965 and 1970, wheat harvests in Pakistan and India almost doubled. This greatly improved food security and helped feed many people in those countries.

Many people called Borlaug "the father of the Green Revolution." He is often credited with saving over a billion people from starvation. He received the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize for helping to increase the world's food supply and promoting world peace. Later in his life, he continued to help countries in Asia and Africa grow more food.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Norman Borlaug was born in 1914 on his grandparents' farm in Iowa, USA. His great-grandparents had moved to the United States from Norway. Norman was the oldest of four children. From age seven to nineteen, he worked hard on his family's farm. He fished, hunted, and helped raise corn, oats, cattle, pigs, and chickens.

He went to a small, one-room schoolhouse for his early education. Today, this school building is part of "Project Borlaug Legacy," which helps remember his work. In high school, Norman played football, baseball, and was on the wrestling team. His wrestling coach always told him to "give 105%," a lesson he carried throughout his life.

Norman's grandfather encouraged him to get more education. He told Norman, "you're wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on." This advice inspired Norman to leave the farm and go to the University of Minnesota in 1933. He didn't pass the entrance exam at first, but he was accepted into a special two-year program. After a while, he moved into the College of Agriculture to study forestry. He also continued wrestling for the university team.

To pay for college, Norman sometimes took breaks from his studies to work. In 1935, he led a group of unemployed people in the Civilian Conservation Corps. He saw many people who were starving, and this experience deeply affected him. He later said, "I saw how food changed them... All of this left scars on me."

Near the end of his forestry studies, Borlaug heard a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman. Stakman talked about plant diseases, especially a fungus called rust that destroys wheat crops. Stakman had found ways to breed plants that could resist rust. Borlaug found this very interesting. When his job with the Forest Service ended, he decided to study plant pathology under Stakman. He earned his Master of Science degree in 1940 and his Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics in 1942.

While in college, Norman met Margaret Gibson, who would become his wife. They married in 1937 and had three children. Margaret passed away in 2007 after 69 years of marriage. Even though he lived in Dallas in his later years, Borlaug spent most of his time traveling the world to help people.

A Career Dedicated to Food

Working for the War Effort

From 1942 to 1944, Borlaug worked as a scientist at DuPont. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, his lab started doing research for the U.S. military. One of his first projects was to create a special glue. This glue needed to hold together boxes of food and supplies that were dropped into the warm, salty water of the Pacific Ocean for soldiers. Within weeks, Borlaug and his team developed a glue that worked! He also worked on things like camouflage and disinfectants.

Starting in Mexico

In 1940, the Mexican government wanted to improve its agriculture and economy. U.S. Vice President-Elect Henry A. Wallace helped persuade the Rockefeller Foundation to work with Mexico on farming development. The Rockefeller Foundation asked Professor Stakman to help. He chose Dr. Jacob George "Dutch" Harrar to lead a new program in Mexico.

Harrar wanted Borlaug to join the team as a geneticist and plant pathologist. Borlaug first wanted to finish his war work at DuPont. But in July 1944, he flew to Mexico City to lead the new Cooperative Wheat Research and Production Program.

In 1964, Borlaug became the director of the International Wheat Improvement Program. This program was part of the new International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). Even after officially retiring in 1979, Borlaug continued to work as a senior advisor at CIMMYT. He also taught and did research at Texas A&M University starting in 1984, where he stayed until his death.

Borlaug believed that pesticides, like DDT, had more benefits than drawbacks for people. He publicly supported their use, even when he faced strong criticism. He also strongly supported agricultural biotechnology, which uses science to improve crops.

Wheat Research in Mexico

The Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program aimed to increase wheat production in Mexico. At the time, Mexico had to import a lot of its grain. Borlaug joined the team in late 1944. Over 16 years, he developed amazing new types of wheat that produced high yields, resisted diseases, and had shorter, stronger stems.

Borlaug said his first few years in Mexico were tough. He didn't have enough trained scientists or equipment. Farmers were also hesitant because they had lost many crops to a disease called stem rust a few years earlier. He spent the first ten years breeding wheat that could fight off diseases like rust. His team made 6,000 different wheat crossings during that time.

Growing Wheat Faster

Borlaug's early work was in the central highlands of Mexico. He realized he could speed up his breeding work by using Mexico's two different growing seasons. He would grow wheat in the central highlands during the summer. Then, he would immediately take the seeds north to a research station in the Yaqui Valley. The different altitudes and temperatures allowed him to grow more crops each year.

This idea, called "shuttle breeding," was very successful. It also had an unexpected benefit: the new wheat types could grow well in many different environments. This meant that the project didn't need to create separate breeding programs for every part of the world.

Stronger, Disease-Resistant Wheat

Plant diseases like rust are always changing. To fight this, Borlaug developed "multiline varieties." These are mixtures of several similar wheat types, each with different genes to resist diseases. If one type became sick, the others would still be healthy, helping to protect the overall crop.

Borlaug also worked on making wheat plants shorter. Older wheat types had tall, thin stems. When farmers used nitrogen fertilizer to help the plants grow faster, the tall stems would often fall over under the weight of the heavy grain. This was called "lodging." In 1953, he found a Japanese dwarf wheat variety called Norin 10. He crossbred this shorter, stronger wheat with his disease-resistant types.

Borlaug's new semi-dwarf, disease-resistant wheat types, like Pitic 62 and Penjamo 62, greatly increased how much wheat could be harvested. By 1963, 95% of Mexico's wheat crops were using these new types. The harvest that year was six times larger than when Borlaug first arrived in 1944. Mexico was now growing enough wheat for itself and even exporting it!

The Green Revolution Spreads

Helping South Asia

In the early 1960s, Borlaug's dwarf wheat types were tested in many places around the world. In 1963, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mexican government sent Borlaug to India to continue his work. He brought hundreds of kilograms of promising wheat seeds.

In the mid-1960s, India and Pakistan faced serious food shortages. In 1965, Borlaug imported about 450 tons of his new wheat seeds for these countries. There were many challenges. One shipment of seeds was delayed by customs and then by riots in Los Angeles. Then, a bank refused to accept a payment because of misspelled words. To make things worse, a war broke out between India and Pakistan.

Despite these problems, the seeds eventually arrived. Borlaug discovered that some seeds had been damaged, so he quickly told farmers to plant twice as many. The first harvests of Borlaug's crops were much larger than any seen before in South Asia. India and Pakistan then decided to buy huge amounts of the new seeds. In 1966, India bought 18,000 tons of seeds, the largest seed purchase in the world at that time.

By 1968, William Gaud of the U.S. Agency for International Development called Borlaug's work a "Green Revolution." The high yields caused new problems, like not enough workers to harvest the crops or places to store the grain. Some local governments even had to close schools temporarily to use them for grain storage!

In Pakistan, wheat harvests almost doubled between 1965 and 1970. Pakistan was growing enough wheat for itself by 1968. In India, harvests also greatly increased. By 1974, India was self-sufficient in growing all its cereals. Since the 1960s, food production in both countries has grown faster than their populations. Borlaug's work helped prevent millions of acres of natural land from being turned into farms.

Nobel Peace Prize

For his huge contributions to the world's food supply, Norman Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. When he was told the news, he thought it was a joke! He was given the award on December 10.

In his Nobel speech, he said that the prize recognized the important role of agriculture in a world that needs both food and peace. He also warned about the "Population Monster," saying that while the Green Revolution offered a "breathing space," people also needed to control population growth.

The Borlaug Hypothesis

Borlaug always argued that increasing crop yields was a way to protect forests. This idea is now called the "Borlaug hypothesis." It suggests that if we grow more food on existing farmland, we won't need to cut down forests to create new farms. This means that high-yield farming methods can actually help save ecosystems from being destroyed.

Later Work and Legacy

After officially retiring, Borlaug continued to teach, research, and advocate for better farming. He spent much of his time at CIMMYT in Mexico and at Texas A&M University.

Helping Africa

In the early 1980s, some groups opposed Borlaug's methods, which made it harder for him to expand his work into Africa. But in 1984, during a terrible famine in Ethiopia, a Japanese businessman named Ryoichi Sasakawa asked Borlaug for help. He convinced Borlaug to start a new effort, and they created the Sasakawa Africa Association (SAA).

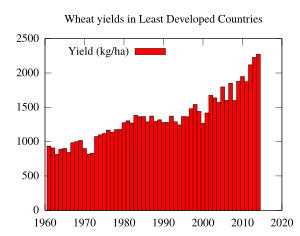

The SAA helps African countries facing food shortages. Borlaug said, "I assumed we'd do a few years of research first, but after I saw the terrible circumstances there, I said, 'Let's just start growing'." Soon, Borlaug and the SAA had projects in seven countries. Maize (corn) harvests in these countries tripled. Other crops like wheat and sorghum also increased. Today, the program works in many African countries that used to suffer from famines.

Since 1986, over 8 million small farmers in 15 African countries have learned SAA farming techniques. These methods have helped them double or even triple their grain production.

World Food Prize

Borlaug created the World Food Prize in 1986. It is an international award that recognizes people who have made great achievements in improving the quality, quantity, or availability of food worldwide. He wanted the prize to highlight important work and inspire others. The first prize was given to his former colleague, M. S. Swaminathan, in 1987.

The Future of Food

Borlaug was concerned about the limited amount of land available for farming. In 2005, he said, "we will have to double the world food supply by 2050." He believed that most of this increase would have to come from land already being used. He suggested focusing on research to make crops more resistant to diseases.

Borlaug also believed that genetically modified organisms (GMOs) were the only way to produce enough food as the world runs out of new farmland. He said GMOs were not dangerous because "we've been genetically modifying plants and animals for a long time."

He warned that if crop yields don't keep increasing, the next century could see "sheer human misery." He also believed that controlling population growth was important to prevent food shortages.

Death and Tributes

Norman Borlaug passed away from lymphoma at age 95 on September 12, 2009, in Dallas, Texas.

His children said they hoped his life would be "a model for making a difference in the lives of others and to bring about efforts to end human misery for all mankind."

Leaders from around the world, including the Prime Minister of India and the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, praised Borlaug's work. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) called him "a towering scientist whose work rivals that of the 20th century's other great scientific benefactors of humankind."

Honors and Awards

Norman Borlaug received many honors for his work. In 1968, a street in Ciudad Obregón, Mexico, where he did some of his first experiments, was named after him.

In 1970, he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his contributions to the "green revolution."

In 1985, the University of Minnesota named a building "Borlaug Hall" in his honor.

In 2013, a statue of him was unveiled in New Delhi, India. On March 25, 2014, a statue of Borlaug was unveiled at the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., on what would have been his 100th birthday.

Besides the Nobel Prize, Borlaug also received the 1977 U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, the 2002 Public Welfare Medal, and the 2004 National Medal of Science. He received 49 honorary degrees from universities in 18 countries. In Iowa and Minnesota, October 16 is known as "Norman Borlaug World Food Prize Day."

In 2006, the Government of India gave him its second-highest civilian award, the Padma Vibhushan. That same year, the United States Senate and House of Representatives voted to give him America's highest civilian award, the Congressional Gold Medal. He received this medal on July 17, 2007.

Several research centers and buildings around the world are named after him, including the Norman E. Borlaug Center for Farmer Training and Education in Bolivia and the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture at Texas A&M University.

Borlaug's life and work have been featured in books and documentaries, showing how one person can make a huge difference in the world.

Books and Lectures

- The Green Revolution, Peace, and Humanity. 1970. Nobel Lecture, Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. December 11, 1970.

- Wheat in the Third World. 1982. Authors: Haldore Hanson, Norman E. Borlaug, and R. Glenn Anderson. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN: 0-86531-357-1

- Norman Borlaug on World Hunger. 1997. Edited by Anwar Dil. San Diego/Islamabad/Lahore: Bookservice International. 499 pages. ISBN: 0-9640492-3-6

- The Green Revolution Revisited and the Road Ahead. 2000. Anniversary Nobel Lecture, Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. September 8, 2000.

- "Ending World Hunger. The Promise of Biotechnology and the Threat of Antiscience Zealotry". 2000. Plant Physiology, October 2000, Vol. 124, pp. 487–90. (duplicate)

- Borlaug, Norman E. (June 27, 2007). "Sixty-two years of fighting hunger: personal recollections". Euphytica 157 (3): 287–97. doi:10.1007/s10681-007-9480-9.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Norman Borlaug para niños

In Spanish: Norman Borlaug para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |