Ottoman Serbia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ottoman Serbia

Историја Србије у Османском царству (Serbian)

|

|

|---|---|

| 1459–1804 | |

| Common languages | Serbian |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official) Christianity (Serbian Orthodox Church, Roman Catholicism) |

| Demonym(s) | Serb |

| Government | |

| Beylerbey, Pasha, Agha, Dey | |

| History | |

|

• Conquest of Smederevo

|

1459 |

|

• Serbian Revolution

|

1804 |

| Today part of | Serbia |

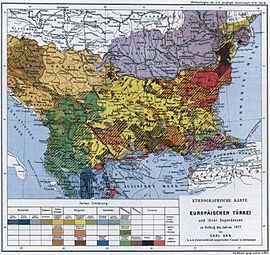

Most of what is now Serbia was part of the Ottoman Empire from the mid-1400s to the early 1800s. Some parts were directly ruled as provinces (called eyalets), while others were like smaller states that had to obey the Ottomans (called vassal states). By the early 1700s, the northern region of Vojvodina was no longer under Ottoman control. It was given to the Habsburgs, a powerful European family.

In the 1400s, the Serbian Despotate (a Serbian kingdom) was taken over by the Ottoman Empire. This was part of the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. The Ottomans first defeated the Serbs at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371. This made the southern Serbian leaders their vassals. Soon after, the Serbian Emperor Stefan Uroš V died without children. Since the nobles could not agree on a new ruler, the empire split into smaller areas ruled by local lords. These lords often fought among themselves.

The strongest of these lords was Lazar of Serbia. His region, in central Serbia, was not yet under Ottoman rule. He faced the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Both armies suffered huge losses, and Serbia eventually fell to the Ottomans. Lazar's son, Stefan Lazarević, became the new ruler. By 1394, he also became an Ottoman vassal. In 1402, he stopped obeying the Ottomans and became an ally of Hungary. For many years, the Ottomans and Hungary fought over Serbia. In 1459, Serbia was fully taken over by the Ottomans.

Over the centuries, Serbs tried to rebel against Ottoman rule several times. These revolts were usually small and did not last long. They often happened with help from the Habsburgs. Some important revolts include the Banat Uprising in 1594, and others in 1688–1691, 1718–1739, and 1788.

In 1799, a group of janissary leaders (elite Ottoman soldiers) called dahias took control of the Sanjak of Smederevo (a region in Serbia). They stopped obeying the Sultan and made people pay much higher taxes. In 1804, they murdered many important Serbian thinkers and nobles. This event is known as the Slaughter of the Dukes. In response, the Serbs started a rebellion. By 1806, they had killed or driven out all the dahias. But the fighting did not stop. When the Sultan sent a new governor (called a Pasha), the Serbs killed him too.

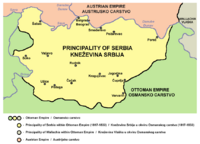

The revolt continued and became known as the First Serbian Uprising. Serbs, led by Karađorđe, defeated the Ottomans in several battles. They freed most of Central Serbia. A smaller rebellion failed in 1814. Then, in 1815, the Second Serbian Uprising began. By 1817, Serbia was almost independent. It became known as the Principality of Serbia.

Contents

History of Ottoman Rule in Serbia

Early Conflicts and Ottoman Conquest (1389–1540)

The Ottomans won a very important battle against the Serbian army in 1371. This was the Battle of Maritsa. The forces of Vukašin of Serbia and Uglješa Mrnjavčević were defeated. This ended any hope of reuniting the Serbian Empire. From then on, Serbia was mostly defending itself.

The biggest battle was the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Lazar of Serbia, Vuk Branković, and Vlatko Vuković fought against the best troops of Sultan Murad I. Both Sultan Murad I and Prince Lazar died in this bloody battle. The outcome was not clear, but Serbia lost many soldiers.

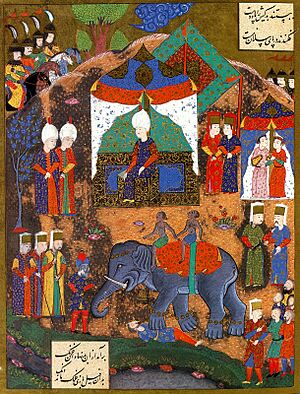

The Battle of Kosovo decided Serbia's future for a long time. Serbia no longer had a strong army to fight the Ottomans directly. This was a difficult time. Prince Lazar's son, Stefan Lazarević, became the ruler (called a despot). He was a brave knight, a military leader, and a poet. At first, Stefan was a vassal of Sultan Bayezid I. He fought well for the Ottomans in battles like Battle of Nicopolis (1396) and Battle of Ankara (1402). After Bayezid I lost power, Stefan became independent.

His cousin and heir, Đurađ Branković, moved the capital to a new strong city called Smederevo. The Ottomans continued to conquer Serbian lands. In 1459, Smederevo fell, and all of northern Serbia was taken. Only parts of Bosnia and Zeta remained free. After the Principality of Zeta fell in 1496, the Ottoman Empire ruled Serbia for nearly 300 years.

A Serbian principality (a small state) was later formed under Hungarian protection. This was in what is now Vojvodina, Slavonia, and Bosnia. It was led by the Branković family and other Serbian nobles. This state constantly fought the Ottomans. It kept alive the memory of the old Serbian Kingdom.

Serbs and Hungary (1389–1540)

From the 1300s, more and more Serbs moved north to Vojvodina. This region was then part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian kings welcomed Serbs. They hired many Serbs as soldiers and guards for their borders. Because of this, the Serb population in this area grew a lot.

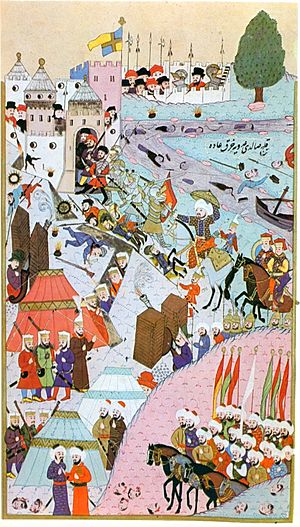

During the wars between the Ottoman Empire and Hungary, these Serbs tried to bring back the Serbian state. On August 29, 1526, the Ottoman army destroyed the Hungarian army at the battle of Mohács. The Hungarian king, Louis II of Hungary, was killed. After this battle, Hungary split into three parts. Much of its land became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Soon after, a leader of Serbian soldiers in Hungary, Jovan Nenad "The Black", took control of Bačka, northern Banat, and part of Srem. These areas are now in Vojvodina. He created his own state with Subotica as its capital. At his strongest, Jovan Nenad crowned himself the Serb emperor in Subotica. However, Hungarian nobles in the region teamed up against him. They defeated his troops in the summer of 1527. Emperor Jovan Nenad was killed, and his state collapsed.

After the Siege of Belgrade (1521), Suleiman I moved some Serbs to a forest near Constantinople. This area is now called Bahçeköy, or "Belgrade forest."

Serbs and Austria

European powers, especially Austria, often fought wars against the Ottoman Empire. They relied on the help of Serbs living under Ottoman rule. During the Austro-Turkish War (1593–1606), Serbs in Banat (a region in the Ottoman Empire) started an uprising in 1594. In response, Sinan Pasha ordered the burning of the remains of Saint Sava. Saint Sava is the most important Serbian saint.

Serbs also created another center of resistance in Herzegovina. But when Turkey and Austria signed a peace treaty, the Serbs were left alone to face Ottoman revenge. This pattern happened many times over the next centuries.

The Great Turkish War (1683–1699)

The Great Turkish War happened between the Ottomans and the Holy League from 1683 to 1699. The Holy League was a group of countries including Austria, Poland, and Venice. It was supported by the Pope. These powers encouraged Serbs to rebel against the Ottomans. Soon, uprisings and small-scale fighting (called guerrilla warfare) spread across the western Balkans. This included areas from Montenegro to the Danube river and Old Serbia.

However, when the Austrians began to leave Serbia, they invited the Serbian people to move north with them into Austrian lands. Serbs had to choose between Ottoman punishment and living in a Christian state. Many Serbs left their homes and moved north, led by their church leader, patriarch Arsenije Čarnojević. This event is known as the Great Migrations of the Serbs.

Austrian-Ottoman War (1716–1718)

Another important event happened between 1716 and 1718. Serbian lands, from the Drina river to Belgrade and the Danube, became a battlefield. This was during a new Austrian-Ottoman war started by Prince Eugene of Savoy. The Serbs once again sided with Austria. After a peace treaty was signed in Požarevac, the Ottomans lost all their lands in the Danube region and northern Serbia. They also lost northern Bosnia, and parts of Dalmatia and the Peloponnesus.

The last Austrian-Ottoman war was the Dubica War (1788–1791). During this war, the Austrians encouraged Christians in Bosnia to rebel. No more major wars were fought between Austria and the Ottomans until the 1900s. By then, both empires (Austria had become Austria-Hungary) eventually fell apart.

Serbian Revolts Against Ottoman Rule

Banat Uprising (1594)

In the Banat region, which was then part of the Ottoman province of Temeşvar, a large uprising began in 1594. This was near the city of Vršac. It was the biggest uprising of Serbs against Ottoman rule up to that time. The leader was Teodor Nestorović, the Bishop of Vršac. Other leaders included Sava Ban and Velja Mironić.

For a short time, the Serb rebels captured several cities in Banat. These included Vršac, Bečkerek, and Lipova. They also took Titel and Bečej in Bačka. A Serbian folk song shows how big this uprising was: "The whole land has rebelled, six hundred villages arose, everybody pointed his gun against the emperor!"

This rebellion was seen as a holy war. The Serb rebels carried flags with the image of Saint Sava. Sinan Pasha, who led the Ottoman army, ordered the green flag of Muhammad to be brought from Damascus to fight the Serbian flag. He also burned the remains of Saint Sava in Belgrade.

Serb Uprising of 1596–97

The Serb Uprising of 1596-97 was planned by Patriarch Jovan Kantul and led by Grdan.

Plans for Revolts with Russian Help

Sava Vladislavich, a Serb who worked for Russia, kept in touch with other Serbs. He believed they would rebel against the Sultan if the Russian Tsar invaded nearby lands. In 1711, Tsar Peter sent him to Moldavia and Montenegro. Vladislavich was supposed to encourage the people there to rebel. Not much came of these plans, even with help from a pro-Russian colonel, Michael Miloradovich.

Later, Petar I Petrović-Njegoš, the Prince-Bishop of Montenegro, had a plan. He wanted to create a new Serbian Empire. It would include Bosnia, Serbia, Herzegovina, Montenegro, and the Boka region. He wanted Dubrovnik to be its capital. In 1807, he wrote to a Russian general about this. He suggested that the Russian Tsar would be the "Tsar of the Serbs." The Metropolitan of Montenegro would be his helper. He believed Montenegro should lead the effort to bring back the Serbian Empire.

Habsburg Takeovers (1686–1793)

From 1718 to 1739, the country was known as the Kingdom of Serbia (1718–1739). After the Habsburgs lost control of Serbia, many Serbs moved from the Ottoman Empire into the Austrian Empire. This was part of the Great Migrations of the Serbs.

Later in the 1700s, an officer named Koča Anđelković led a successful rebellion against the Ottomans. He had help from Austria. This briefly put Serbia back under Habsburg rule. This area was called Koča's frontier. The rebellion ended with a peace treaty, and the Austrians left.

Sava Tekelija's Vision

Sava Tekelija was a Serbian nobleman and a lawyer. He was very important in the cultural and political life of Serbs in the Habsburg Empire. In 1790, he gave a famous speech. He argued that Serbian rights should be officially added to Hungarian law. He believed that laws were stronger than the will of individuals or rulers. This would protect Serbian rights better.

During the First Serbian Uprising, he made a map of Serbian lands. This map showed his political goals. He wrote to Napoleon Bonaparte suggesting a South Slavic state with Serbia at its center. This state would include lands conquered by France. He wanted France to help the Serbian Revolution. This would stop Russia from gaining too much power in the region. He sent a similar letter to Austrian Emperor Francis I in 1805. His goal was always to prevent Russian influence. His ideas showed his vision for the future of South Slavic nations.

Events Leading to Uprising (1791–1804)

The Austrians left Serbia in 1791. This ended the Kočina Krajina Serb rebellion, which Austria had started in 1788. Austria needed to end the war, so they gave the Belgrade region back to the Ottoman Empire. Austria had promised to protect the Serbs who rebelled. But many of them and their families still had to leave Serbia and go to Austria.

The Ottoman government tried to make things easier for Serbs for a while. But by 1799, the Janissary soldiers had returned. They took away Serbian self-rule and greatly increased taxes. They also enforced strict military rule in Serbia.

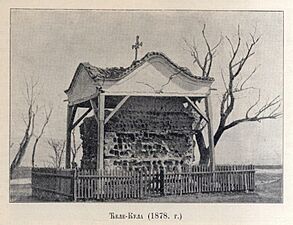

Serbian leaders on both sides of the Danube river began to plan against the dahias (the Janissary leaders). When the dahias found out, they gathered and murdered dozens of Serbian noblemen. This happened in the main square of Valjevo in 1804. This event is known as Seča knezova (the Slaughter of the Dukes).

The massacre made the Serbian people very angry. It started a revolt across the Pashaluk of Belgrade (the Ottoman province). Within days, in the small village of Orašac, Serbs gathered to start the uprising. They chose Karađorđe Petrović as their leader. That afternoon, a Turkish inn in Orašac was burned. Its residents either ran away or were killed. Similar actions happened across the country. Soon, the cities of Valjevo and Požarevac were freed. The Serbs then began to surround Belgrade.

At first, the rebels fought to get back their local rights within the Ottoman system. This was until 1807. They were supported by wealthy Serbs from the Austrian Empire and Serb officers from the Austrian border regions. The Serbs offered to be protected by the Austrian, Russian, and French Empires. They became a new political force during the Napoleonic wars in Europe.

First Serbian Uprising (1804–1813)

During the First Serbian Uprising (1804–1813), Serbia felt like an independent state for the first time. This was after 300 years of Ottoman and short Austrian rule. The Russian Empire encouraged the Serbs. Demands for self-rule in 1804 grew into a war for independence by 1807.

The Serbian revolution mixed old Serbian traditions with modern national goals. It attracted thousands of volunteers from Serbs across the Balkans and Central Europe. This revolution became a symbol for how new nations were formed in the Balkans. It also caused peasant unrest among Christians in Greece and Bulgaria.

After a successful siege with 25,000 men, Karađorđe Petrović declared Belgrade the capital of Serbia on January 8, 1807.

Serbs responded to the Ottoman cruelties by creating their own government. They set up a Governing Council, the Great Academy (a school), and a Theological Academy. Karađorđe and other leaders sent their children to the Great Academy. Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, who later reformed the Serbian alphabet, was also a student there.

Belgrade was repopulated by local military leaders, merchants, and craftspeople. Many educated Serbs from the Habsburg Empire also moved there. They gave a new cultural and political shape to Serbia's peasant society. Dositej Obradović, a famous thinker from the Balkan Age of Enlightenment, founded the Great Academy. In 1811, he became the first Minister of Education in modern Serbia.

In 1812, France invaded Russia. Because of this, the Russian Empire stopped supporting the Serb rebels. The revolutionaries did not want anything less than full independence. But the Ottomans attacked Serbia and forced them to surrender. About a quarter of Serbia's population (around 100,000 people) had to leave and go to the Habsburg Empire. This included Karađorđe Petrović, the leader of the Uprising.

The Ottomans recaptured Belgrade in October 1813. They took brutal revenge. Hundreds of citizens were killed, and thousands were sold into slavery as far away as Asia. Direct Ottoman rule also meant that all Serbian institutions were shut down. This included the University of Belgrade. Ottoman Turks returned to Serbia.

Hadži-Prodan's Revolt (1814)

Even though the Serbs lost the First Uprising, tensions remained high. In 1814, an unsuccessful revolt was started by Hadži Prodan Gligorijević. He was a veteran of the First Serbian Uprising. He knew the Ottomans would arrest him, so he decided to fight back. Milos Obrenović, another veteran, felt it was not the right time for a revolt and did not help.

Hadži Prodan's Uprising quickly failed, and he fled to Austria. After a riot at a Turkish estate in 1814, the Turkish authorities killed many local people. They publicly executed 200 prisoners in Belgrade. By March 1815, Serbs had held several meetings. They decided to start a new revolt.

Second Serbian Uprising (1815–1817)

The Second Serbian Uprising (1815–1817) was the next part of the Serbian national revolution against the Ottoman Empire. It began soon after the Ottomans brutally took over the country again. It also started after Hadži Prodan's revolt failed. The revolutionary council declared an uprising in Takovo on April 23, 1815. Milos Obrenović was chosen as the leader, while Karađorđe was still in exile in Austria.

The Serb leaders made this decision for two main reasons. First, they feared the Ottomans would kill more Serbian nobles. Second, they heard that Karađorđe was planning to return from Russia. The group that opposed Karađorđe, including Miloš Obrenović, wanted to act first. They wanted to keep Karađorđe from regaining power.

Fighting began again at Easter in 1815. Milos became the main leader of the new revolt. When the Ottomans found out, they sentenced all the leaders to death. The Serbs fought in battles at Ljubić, Čačak, Palez, Požarevac, and Dublje. They managed to win back the Pashaluk of Belgrade.

Milos chose a policy of restraint. Captured Ottoman soldiers were not killed, and civilians were released. His stated goal was not full independence. He wanted to end the harsh and unfair Ottoman rule.

Larger events in Europe helped the Serbian cause. Political talks and diplomacy between the Prince of Serbia and the Ottoman Porte (the Ottoman government) replaced further fighting. This fit with the political rules of Europe at the time. Prince Miloš Obrenović was a smart politician and a good diplomat. To show his loyalty to the Ottomans, he ordered the assassination of Karađorđe Petrović in 1817.

Napoleon's final defeat in 1815 made the Ottomans worried that Russia might get involved in the Balkans again. To avoid this, the Sultan agreed to make Serbia a suzerain state. This meant Serbia would be semi-independent, but still officially answer to the Ottoman government.

Ottoman Serbs and Their Identity

Ottoman Serbs were Serbian Orthodox Christian. They belonged to the Rum Millet (meaning "Roman Nation"). This was a system where the Ottoman Empire grouped people by their religion. Even though there wasn't an official "Serbian millet," the Serbian Church was the recognized organization for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire.

-

Islam-aga's Mosque, Niš, built in 1720

-

Stari Han caravanserai in Kremna, Užice, early 19th century

See also

- Serbia in the Middle Ages

- Byzantine Serbia

Sources

- Zirojević, O. (1974) Tursko vojno uređenje u Srbiji, 1459–1683. Beograd: Istorijski institut

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |