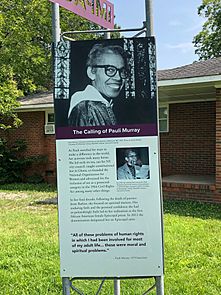

Pauli Murray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pauli Murray |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Anna Pauline Murray |

| Born | November 20, 1910 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1985 (aged 74) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Spouse | Billy Wynn (1930–1949, annulled) |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 1 July |

| Venerated in | Episcopal Church (United States) |

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (November 20, 1910 – July 1, 1985) was an American civil rights activist. She became a lawyer, a champion for gender equality, an Episcopal priest, and an author. In 1977, she made history. She became one of the first women and the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland. She was raised mostly by her aunt in Durham, North Carolina. At 16, she moved to New York City. She attended Hunter College and earned a degree in English in 1933. In 1940, Murray and a friend were arrested in Virginia. They sat in the whites-only section of a bus. This event inspired her to become a civil rights lawyer.

She studied law at Howard University. She was the only woman in her class. Murray graduated at the top of her class. However, she was not allowed to study at Harvard University because she was a woman. She called this unfair treatment "Jane Crow." This term was similar to "Jim Crow laws," which enforced racial segregation. She later earned more law degrees from University of California, Berkeley and Yale Law School. In 1965, she was the first African American to get a Doctor of Juridical Science from Yale.

As a lawyer, Murray fought for civil rights and women's rights. Thurgood Marshall, a famous civil rights lawyer, called her 1950 book, States' Laws on Race and Color, the "bible" of the civil rights movement. President John F. Kennedy chose her to serve on a commission for women's status in 1961. In 1966, she helped start the National Organization for Women. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a future Supreme Court Justice, recognized Murray's work on gender discrimination. Murray also taught at the Ghana School of Law and Brandeis University.

In 1973, Murray decided to join the Episcopal Church. She became an ordained priest in 1977. This made her one of the first women priests. Besides her legal work, Murray wrote two autobiographies and a book of poems. Her poetry book, Dark Testament, was re-published in 2018.

Contents

Pauli Murray's Early Life

Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910. Her family had a mix of backgrounds. They included Black slaves, white slave owners, Native Americans, and Irish people. Her family was called a "United Nations in miniature."

Murray's parents were William H. Murray and Agnes Fitzgerald Murray. Her mother, Agnes, was a nurse. She died in 1914 when Pauli was three years old. After her father became ill, relatives took care of the children.

Three-year-old Pauli went to Durham, North Carolina. She lived with her mother's family. Her aunts, Sarah and Pauline, who were teachers, raised her. Her grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald, also helped. She attended St. Titus Episcopal Church with her family. When she was twelve, her father was sent to a hospital. He died there in 1923.

Murray lived in Durham until she was 16. Then she moved to New York to finish high school. She lived with her cousin's family. She graduated from Richmond Hill High School in 1927. She then went to Hunter College for two years.

Murray secretly married William Roy Wynn in 1930. But she soon regretted it. They spent only a few months together. Their marriage was later ended in 1949.

Murray wanted to go to Columbia University. But the university did not accept women. She also could not afford to go to its women's college. So, she attended Hunter College. It was a free college for women. She was one of the few students of color there. One of her English teachers encouraged her writing. This led to her memoir Proud Shoes (1956). She graduated in 1933 with a degree in English.

It was hard to find jobs during the Great Depression. Murray worked selling subscriptions for Opportunity. This was a journal from the National Urban League. She had to quit due to poor health. Her doctor suggested a healthier environment.

Murray then worked at Camp Tera. This was a "She-She-She" conservation camp. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt helped start these camps. They gave jobs to young adults. Murray's health improved there. She also met Eleanor Roosevelt. They later became friends and wrote letters to each other.

Early Activism and Law School

In 1938, Murray applied to a PhD program. It was at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She was rejected because of her race. All public places in the South were segregated by law. Her case became widely known. The NAACP first showed interest but later did not represent her.

In 1940, Murray was arrested in Petersburg, Virginia. She and a friend moved from the back of a bus to the white section. They were inspired by Gandhi's idea of civil disobedience. They refused to move back. They were jailed. The Workers' Defense League (WDL) paid her fine. Murray then worked for the WDL.

Murray became involved in the case of Odell Waller. He was a Black sharecropper sentenced to death. The WDL argued that Waller acted in self-defense. Murray traveled to raise money for his appeal. She wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Roosevelt asked the Virginia governor to ensure a fair trial. She also asked the president to request a lighter sentence. Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt became good friends. Despite their efforts, Waller was executed in 1942.

Studying Law at Howard University

The bus incident and the Waller case inspired Murray to study law. In 1941, she started at Howard University law school. She was the only woman in her class. She noticed unfair treatment against women. She called this "Jane Crow." This was like "Jim Crow," which meant racial discrimination. On her first day, a professor questioned why women went to law school. This made her angry.

In 1942, Murray joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). She wrote an article against segregation in the US military. She also took part in sit-ins. These challenged restaurants with unfair seating rules. These actions happened before the bigger sit-ins of the 1950s and 1960s.

Murray became chief justice of the Howard Court of Peers. This was the highest student position. In 1944, she graduated first in her class. Usually, men who graduated first got fellowships for Harvard University. But Harvard did not accept women. Murray was rejected. She wrote a letter asking them to change their minds.

She continued her studies at Boalt Hall School of Law at University of California, Berkeley. Her master's thesis was about equal opportunity in jobs. It said that "the right to work is an inalienable right." It was published in the California Law Review.

Pauli Murray's Professional Career

After passing the California bar exam in 1945, Murray became California's first Black deputy attorney general. This was in January 1946. The National Council of Negro Women named her "Woman of the Year." Mademoiselle magazine also honored her in 1947. Murray was the first Black woman hired at the Paul, Weiss law firm in New York City. She worked there from 1956 to 1960.

Fighting for Rights

Murray was a strong activist. She worked alongside leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. She created the term Jane Crow. This showed her belief that Jim Crow laws also hurt African-American women. She wanted to stop both racism and sexism.

In 1950, Murray published States' Laws on Race and Color. This book looked at state segregation laws. She used ideas from psychology and sociology. This was a new way to discuss legal issues. Murray argued that civil rights lawyers should challenge segregation laws directly. She said they were unconstitutional. Thurgood Marshall called her book the "bible" of the civil rights movement. Her ideas helped the NAACP in the Brown v. Board of Education case (1954). The US Supreme Court ruled that segregated public schools were illegal.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. She wrote a memo arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment should also stop sex discrimination.

In 1963, she spoke out against sexism in the civil rights movement. She wrote a letter to A. Philip Randolph. She criticized that no women were invited to give major speeches at the 1963 March on Washington. She said:

I have been increasingly worried about the big difference between the important role Negro women have played in our struggle and the small leadership role they have been given in national decisions. It is wrong to have a national march on Washington and not include a single woman leader.

In 1964, Murray wrote an important legal paper. It helped add "sex" as a protected group to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1965, she published "Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII." This article compared laws against women to Jim Crow laws.

In 1966, she helped found the National Organization for Women (NOW). She hoped it would be like the NAACP for women's rights. In 1966, she and Dorothy Kenyon won the case White v. Crook. This ruling said women have an equal right to serve on juries. Ruth Bader Ginsburg later named Murray and Kenyon as coauthors on a legal brief. This was for the 1971 Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed.

Teaching and Academia

Murray lived in Ghana from 1960 to 1961. She taught at the Ghana School of Law. She returned to the US and studied at Yale Law School. In 1965, she became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale.

Murray was vice president of Benedict College from 1967 to 1968. She then became a professor at Brandeis University. She taught there from 1968 to 1973. She became a full professor in American studies in 1971. She taught law and also started classes on African-American studies and women's studies. These were new for the university.

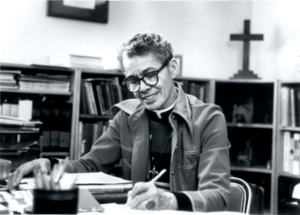

Becoming a Priest

In 1973, Murray left teaching. She felt a strong connection to the Episcopal Church. She was over sixty years old. She attended General Theological Seminary. She earned a Master of Divinity degree in 1976.

She became a deacon in 1976. Then, in 1977, she was ordained as an Episcopal priest. This made her the first African-American woman to be an Episcopal priest. She was among the first group of women priests. That year, she celebrated her first Eucharist and preached her first sermon. This was the first time a woman celebrated the Eucharist in an Episcopal church in North Carolina. In 1978, she preached in her hometown of Durham, North Carolina. She announced her mission of reconciliation. For the next seven years, Murray worked in a church in Washington, DC. She focused on helping the sick.

Pauli Murray's Legacy

Pauli Murray passed away on July 1, 1985. She died from pancreatic cancer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 2012, the Episcopal Church decided to honor Murray. She is now remembered as one of its Holy Women, Holy Men. Her feast day is July 1, the day she died. Bishop Michael Curry said this honor is for "people whose lives have shown what it means to follow Jesus."

In 2015, Murray's childhood home in Durham, North Carolina, was named a National Treasure. In April 2016, Yale University announced a new residential college would be named after her: Pauli Murray College.

In December 2016, the Pauli Murray Family Home became a National Historic Landmark. In 2018, Murray was chosen as an honoree for Women's History Month in the United States. Also in 2018, she became a permanent part of the Episcopal Church's calendar of saints.

In January 2021, a documentary called My Name Is Pauli Murray was released.

Pauli Murray's Writings

Besides her legal work, Murray wrote two autobiographies and a book of poetry. Her first autobiography, Proud Shoes (1956), tells the story of her family. It focuses on her maternal grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald. Cornelia was born into slavery. Robert was a free Black man. He moved South to teach after the Civil War. Newspapers, including The New York Times, gave the book very good reviews.

Murray published her poetry collection, Dark Testament and Other Poems, in 1970. The book contains poems about love and also about unfairness. The poem "Ruth" is in the 1992 book Daughters of Africa. Dark Testament was republished in 2018.

A second autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published after her death in 1987. Song focused on Murray's own life. It talked about her struggles with both gender and racial discrimination. It won several awards, including the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

Works by Murray

Law Books

- Murray, Pauli (Editor) (1952) States' Laws on Race and Color (Studies in the Legal History of the South), Athens: University of Georgia Press, Reprint edition, 2016. ISBN 9-780-8203-5063-9

- Murray, Pauli and Rubin, Leslie. The Constitution and Government of Ghana, London: Sweet & Maxwell, 1964. ISBN 978-0421041806, OCLC 491764185

Poetry

- Dark Testament and Other Poems, Connecticut: Silvermine Publishers, 1970. ISBN: 978-0-87321-016-4

Autobiographies

- Proud Shoes: The Story Of An American Family, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956. ISBN: 0-8070-7209-5.

- Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, New York: Harper & Row, 1987. ISBN: 0-06-015704-6. Reissued as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest and Poet, University of Tennessee Press, 1989. ISBN: 0-87049-596-8

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Pauli Murray para niños

In Spanish: Pauli Murray para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |