Philip McShane facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Philip McShane

|

|

|---|---|

University of British Columbia, July 2014

|

|

| Born |

Philip Joseph McShane

18 February 1932 Bailieborough, County Cavan, Ireland

|

| Died | 1 July 2020 (aged 88) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | mathematical physics, evolutionary theory, economics, methodology, theology |

| Thesis | The Concrete Logic of Discovery of Statistical Science |

Philip McShane (born February 18, 1932 – died July 1, 2020) was an Irish mathematician and philosopher. He was also a theologian, which means he studied religious beliefs and practices.

Philip started his studies in mathematics, physics, and chemistry in the 1950s. Later, he explored philosophy from 1956 to 1959. In 1960, he taught subjects like physics and engineering to university students. After that, he began studying theology in 1963 and economics in 1968.

Over 60 years, McShane wrote many articles and 25 books. His writings covered topics from math and probability to how things change over time (evolution) and how we can think better (critical thinking). He also wrote about education and economics. Starting in 1970, he helped organize international meetings about working together and new ideas in education and economics.

Two special books, called Festschrift volumes, were published to honor McShane. One came out in 2003 and the other in 2022. Many people wrote essays for these books to celebrate his work. McShane was even nominated for the Templeton Prize in 2011 and 2015, which is a big award for people who explore life's deepest questions.

Contents

Life and Education: Philip McShane's Journey

Philip McShane was born in Bailieborough, a town in County Cavan, Ireland. His family later moved to Dublin, where he attended O'Connell School. He continued his studies while training to become a Jesuit priest.

He earned degrees from University College Dublin in science, including a master's in relativity and quantum mechanics. He also studied at St Stanislaus College, Tullabeg, Heythrop College, and Campion Hall, Oxford. McShane taught mathematics at University College Dublin and philosophy at the Milltown Institute of Theology and Philosophy.

In 1950, McShane joined the Jesuits. Even after a head injury that made studying difficult, he took on a challenging program in math, physics, and chemistry. Eleven years later, he became a Jesuit priest.

In 1956, McShane began studying the works of Bernard Lonergan, a famous philosopher and theologian. This became a major focus of his life. He also wrote his own books, like Music That Is Soundless. In the mid-1960s, he studied at Oxford University. In 1969, he finished his doctoral thesis on statistics, which was later published as Randomness, Statistics, and Emergence.

After a big conference in 1970, McShane edited two books of papers from the event. In 1972, he decided to leave the Jesuits. In 1975, he helped start the Dublin Lonergan Centre. He also taught philosophy at Mount Saint Vincent University in Canada from 1974 to 1994.

After retiring from teaching in 1995, McShane wrote many more books. He also traveled the world, giving speeches at conferences in Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Americas. In his later years, McShane wrote about the "Anthropocene age." This is a time when human actions greatly affect the Earth. He imagined a future where people work together like starlings flocking together.

When McShane passed away in July 2020, many people remembered him fondly. Colleagues described him as a wise mentor and a true friend who encouraged long-term thinking.

Influences: Ideas That Shaped Philip McShane

Philip McShane was inspired by many different thinkers and artists throughout his life. He admired the music of Chopin and the geometry of Descartes. He also enjoyed working with physicist Lochlainn O'Raifeartaigh.

McShane greatly appreciated Richard Feynman's Lectures on Physics. He often quoted poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Patrick Kavanaugh. Music was also very important to him. He saw the slow growth of notes in Bruckner's 8th symphony as a symbol for how global teamwork could slowly develop.

In his thoughts on history, McShane referred to the works of Karl Jaspers, Arnold Toynbee, and Eric Voegelin. He also mentioned the teachings of the Buddha and the music of Beethoven. He even cited Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poetry and William Shakespeare's plays. McShane was fascinated by Archimedes' clever invention of the hydrodynamic screw.

Many women also influenced McShane's ideas. His writings on the "Interior Lighthouse" were inspired by Teresa of Ávila's Interior Castle. He admired the novelist Mary Ann Evans and often quoted her work. He also found inspiration in the songs of Sinead O'Connor. McShane appreciated the amazing tennis skills of Serena Williams and Venus Williams. He also valued the work of music teacher Nadia Boulanger and economist Joan Robinson. He even corresponded with urban planner Jane Jacobs.

McShane was deeply influenced by Bernard Lonergan. He spent over 60 years studying Lonergan's major work, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding. McShane's own doctoral thesis aimed to build on Lonergan's ideas about randomness and how things emerge. He also edited some of Lonergan's unpublished works, like For a New Political Economy.

In 2011, McShane was recognized for his important contributions to understanding Lonergan's ideas at Loyola Marymount University. He believed that Lonergan's work was a powerful tool for understanding human knowledge.

Understanding the World: Philip McShane's Ideas

Developing a Worldview: Weltanschauung

McShane spent his life thinking about how we see the world, which he called Weltanschauung. He wanted to create a way of thinking that was not just abstract but also practical. He believed that understanding how physics relates to chemistry, and chemistry to biology, is a key part of a complete worldview.

In his book Music That Is Soundless (1969), McShane wrote about the importance of conversations. He called this a "bud in our birth that clamours in solitude." He encouraged people to think about when they truly understood or were understood. He believed that real conversations are essential for a good worldview.

McShane suggested that humans can have "conversations about conversations." This means we can think about how we understand, listen, and speak. By doing this, we can improve our ability to connect with others. He noted that it can be hard to have real conversations if society doesn't encourage them.

In his book Wealth of Self and Wealth of Nations (1975), McShane invited readers to explore their own "inner dynamics" of understanding. He used simple diagrams to help people grasp how they understand things, make decisions, and believe. He argued that changing our point of view is necessary for human survival. However, he also noted that it's hard to see the need for change until you've already changed your perspective.

McShane believed that asking "What is understanding?" is a scientific quest. His ideas were shaped by his studies in relativity theory and quantum mechanics. He saw a path to understanding the world by looking at how ideas and knowledge emerge.

Studying How Things Grow: Organic Development

McShane was very interested in how living things develop. He wanted to create a "genetic logic" to understand biological growth. Around 2005, this became a central focus for him. He wrote essays to better understand a paragraph in Lonergan's Insight about studying organic development.

He described a three-step process for studying how organisms grow:

- First, describe the different parts of an organism.

- Second, connect these parts to events and actions.

- Third, move from describing what we see to understanding the deeper chemical and physical processes. This links physiology with biochemistry and biophysics.

McShane believed this three-step process was a major challenge for scholars. He added that "self-study of an organism begins from the thing-for-us," meaning we start by observing what our senses tell us. He called the need to guide human development "a missing link."

In his last book, Interpretation from A to Z (2020), McShane was still focused on studying organic development. He wanted to replace simple ideas about genes with a deeper understanding of how things grow. He believed we need to invent new ways to describe these complex processes. He called this "aggreformism," a new word he created. This new way of thinking would help us avoid making up myths instead of doing real science.

Two-Flow Economics: A New Way to See Money

In 1968, McShane began studying Lonergan's ideas on economics. He spent many years trying to understand and explain these ideas. He presented them in various countries, showing how they differed from traditional economic theories like Marxist or Keynesian models.

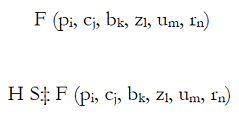

McShane talked about "a triple paradigm shift in economic thinking" that he learned from Lonergan.

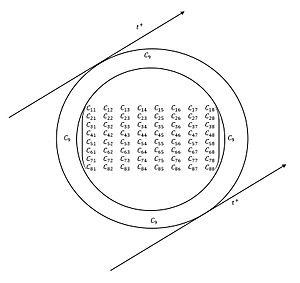

- The first shift is from a simple "one-flow" view of money to a "two-flow" dynamic analysis. This means seeing two different types of money movement.

- The second shift is towards a new way of global teamwork that will include all areas of study.

- The third shift is about understanding human desires and imagination more deeply.

McShane used an example to explain two-flow economics. Newton combined two types of motion (earthly and celestial) into one theory. But in economics, McShane said we need to do the opposite: separate one idea into two. For example, he distinguished between buying a sandwich (consumer good) and buying the machine that slices the meat for the sandwich (producer good). "Instead of Newton’s great leap to get two into one, we have a great leap of getting one into two."

He argued that current economic models miss a key point: there are two types of businesses. One type makes things for people to use directly, like restaurants. The other type makes things for other businesses, like factories that produce large ovens for restaurants. McShane believed that mixing these two types of businesses together has made economic studies less accurate for centuries. He felt that even modern research on inequality often misses this basic distinction.

McShane's view was that to truly understand economics, we must recognize these two types of businesses. This simple idea, he said, leads to seeing "pretty well two of everything" in the economy. Without this understanding, ideas for improving living standards or analyzing global trade can be misleading.

Working Together: Global Collaboration

The Need to "Turn to the Idea"

McShane was interested in the work of Arnie Næss, who is known for "deep ecology." McShane believed that Næss's ideas about "complexity-not-complication" could help us divide work effectively. The challenge is to find ways to solve big global problems like losing animal species, water scarcity, and issues with children's health and education.

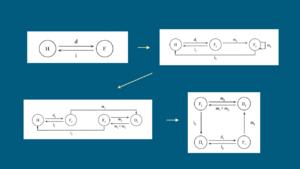

Since the late 1960s, McShane wrote about the idea of dividing up work in a smart way. He was influenced by Bernard Lonergan, who also thought deeply about how to work together efficiently. Lonergan suggested a "third way" for subjects that aren't as successful as natural sciences. This "third way" means finding new methods to avoid becoming average or falling behind.

The idea is to divide the work of caring for the world "functionally." This means not just sticking to separate school subjects, but working together through different steps of a single process. These steps are open and depend on each other, helping to share knowledge with all kinds of people.

McShane believed Lonergan's idea was a breakthrough, like Hedy Lamarr's invention of "frequency hopping" for torpedo guidance. He saw it as a new "wireless technology" for guiding and communicating in the modern world.

One of McShane's contributions was to identify "disciplinary sloping." He noticed that as different subjects move from research to interpretation and history, they start to share data and interests. He explained that Lonergan's idea helped connect all the different parts of theology, like "scattered beads" strung together.

In 2011, McShane spoke about how many specialists would be needed for global collaboration if the world population reached 10 billion. He placed the Standard Model in physics within a larger model of human progress, showing how physics fits into the bigger picture of human development.

The Structure of Dialectic: Honest Conversations

McShane saw "dialectic" as Lonergan's clearest, though not easiest, challenge. Dialectic is a way of having deep, honest conversations to reach a better understanding. McShane wrote many words about this "shocking, brilliant, innovative invitation."

In his book Futurology Express, McShane described dialectic as a mix of private and public tasks. He said that "dialectic elders" need to be flexible, like a great tennis player. They must also be good at noticing "flickers of integral human goings-on." This relates to the task of Comparison, where people check their own ideas and strive for agreement.

Dialectic becomes truly public when people "lay their cards on the table." They ask basic questions, even about themselves, to reach a shared understanding of the past and how to improve it. McShane said that this requires "authentic nescience," which means knowing what you don't know.

In a book published after his death, McShane said dialectic is needed to connect Aristotle's ideas (data, theory, verification) with Drucker's (policy, planning, strategies). He believed that what's missing today is a methodical way to think about how we think. He said that thinking about Archimedes' cleverness can help us change our view of how humans are affecting the world.

McShane encouraged people to be brutally honest about their understanding. In one of his last essays, he compared this to a "calling-out" in a Western film, where good guys and bad guys are clearly identified. He challenged everyone to check their own biases against serious understanding.

Engineering Progress: Building a Better Future

McShane's idea of global teamwork, aimed at "cumulative and progressive results," goes against common ideas about "pure science" versus "applied science." It also challenges the idea of "hard sciences" versus arts and humanities. These old ideas often separate different fields of study.

For example, the ongoing effort to define the "Anthropocene" (the current geological age shaped by humans) often assumes a divide between scientists, humanists, and social scientists. McShane believed this separation was a problem.

McShane traced these old ideas back to Aristotle, who separated theoretical knowledge (about unchanging things) from practical knowledge (about human actions). For Aristotle, it wouldn't make sense to ask if solving scientific questions depends on the character of the person studying nature.

McShane wanted to shake up these old ideas. He replaced the word "metaphysics" (the study of the basic nature of reality) with "futurology" and later with "engineering." He imagined a shared way of thinking about "engineering progress" for the whole world. He was hopeful that some people would take on the challenge of making "resolute and effective intervention in this historical process."

McShane often asked: "Do you view humanity as possibly maturing—in some serious way—or messing along between good and evil?" He believed that expressing and defending your view moves you from just a worldview to a "Praxisweltanschauung," which means a practical worldview. This involves being honest about how you see the future and how you use symbols and structures to "engineer" progress.

Criticism: Challenges and New Ideas

Language, Style, and Clarity: A Unique Voice

One criticism of McShane's work was that his language, new words, and writing style were sometimes hard to understand. He would often speak directly to the reader, asking them to think about themselves. He encouraged readers to look away from the page and reflect, like Gaston Bachelard suggested when reading about a house or a nest.

A long-time friend, Conn O’Donovan, noticed that McShane's writing style changed over time. He wondered if McShane was deliberately letting language "run away with him" to create a new way of scholarly writing. Another colleague noted that while McShane could be very organized, his later works often included new words, jokes, and unusual elements. Some found this helpful, while others found it confusing.

A younger colleague mentioned that McShane strongly believed in "linguistic feedback." This means using language in new ways to help people understand themselves better. An example is changing "heuristic" to "k-euristic" to make a point.

In 2001, before one of Lonergan's books edited by McShane was published, a reviewer criticized McShane's introduction for being "mystifying." McShane replied that he was trying to save the book from "haute vulgarization," which he called "negative haute vulgarization." This means making complex ideas seem simple in a way that loses their true meaning. He quoted Samuel Beckett to explain that direct expression might be hard to understand if people are used to skimming for quick answers.

McShane wondered if he had gone too far or not far enough with his language. He admitted that creating a "child-friendly pedagogy" would require a cultural shift and a new language. He believed that we might need to "write ourselves and the world with a new alphabet, in a new language."

Idiosyncratic Economics: A Different View

In 1977, when McShane applied for a grant to work on economics, one reviewer called his ideas "idiosyncratic economics." This means his economic views were very unique and different from the norm. Thirty years later, a professor said McShane's ideas were not original and could be found in a popular textbook by Gregory Mankiw. More recently, an economist criticized McShane for "overselling" Lonergan's economics.

McShane believed that the basic ideas of "two-flow economic analysis" could be proven and understood even by high school students. However, he knew it would be hard to change economic ideas that were "200 years old." He also realized he had made a mistake in how he taught these ideas. He felt he should have focused more on "statistically-effective outreach," which means teaching in a way that invites and persuades students to understand.

He wrote introductory texts, like the preface to Economics for Everyone, which asked readers to imagine a small bakery and its dependence on other businesses. But he also saw the need for "massively innovative primers" – long, detailed books that would meet the needs of young people today.

Breaking with Tradition: A Challenge to the Norm

McShane often challenged traditional ways of thinking. For example, he was not invited to a conference in Rome about Lonergan's ideas. McShane saw this as a sign that the organizers were avoiding the challenge of "functional collaboration," which was central to his work. He felt they were "muzzling the scientific Lonergan."

Like Lonergan, McShane took seriously the idea that the scientific revolution was a huge turning point in history. Both men pushed for using special symbols and structures to understand things. This approach often surprised people in academic fields that didn't use such methods. McShane said these symbols could "electrify" the fence between common sense and scientific teamwork.

McShane knew that shifting to functional collaboration would be a learning-by-doing process. Since this new way of working was very different from current academic practices, he expected it to be difficult. He often quipped, "If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly," meaning it's worth trying even if you don't do it perfectly at first. He helped organize conferences where authors tried to work together in new ways. He admitted that they "stumbled away" from traditional academic methods.

In 2018, McShane participated in a discussion about Lonergan's Method in Theology. He proposed a new way for panel discussions, but his essay was not published because the journal felt it was more "prophetic exhortations" than new insights. McShane used this rejection as inspiration to write a series of essays challenging the journal.

McShane sometimes called his own efforts "random dialectics," as he rarely experienced the structured conversations he wrote about. He invited colleagues to point out where he had gone wrong in his interpretations, but he often received "disgusting non-scientific silence."

While McShane felt lucky in his education, he knew some of his ideas were "too far out" for his time. He didn't expect much success in his lifetime. He used complex mathematical ideas, like Markov tensors, to imagine the "longitude and latitude" of thinkers like Luther or Descartes on an expanding globe of meaning.

McShane's long-term hope for a creative group of people caring for the world fit with his idea of "emergent probability." This was the main focus of his doctoral thesis. He believed that over millions of years, human collaboration could lead to a "plain plane of radiant life."