Portneuf River (Idaho) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Portneuf River |

|

|---|---|

The Portneuf River, as seen from U.S. Route 30 west of Soda Springs, October 2004

|

|

|

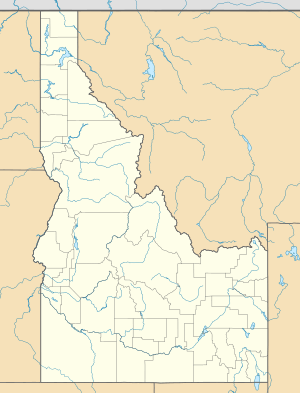

Location of the mouth of the Portneuf River

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Idaho |

| Counties | Bannock, Caribou, Bingham, & Power |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | north of Chesterfield, Bingham County 6,253 ft (1,906 m) 43°06′10″N 112°00′13″W / 43.10278°N 112.00361°W |

| River mouth | Snake River American Falls Reservoir, Bannock/Power counties 4,357 ft (1,328 m) 42°57′06″N 112°45′02″W / 42.95167°N 112.75056°W |

| Length | 124 mi (200 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 1,329 sq mi (3,440 km2) |

The Portneuf River is a river in southeastern Idaho, United States. It flows for about 124-mile-long (200 km). This river is a tributary of the Snake River. It helps drain a valley used for ranching and farming, located in the mountains southeast of the Snake River Plain. The city of Pocatello is built along the Portneuf River. The river is also part of the larger Columbia River Basin.

Contents

Exploring the Portneuf River's Path

The Portneuf River begins in western Caribou County. This is about 25 miles (40 km) east of Pocatello, on the eastern side of the Portneuf Range. It first flows south, curving around the southern end of the 60-mile-long mountain range. Then, it turns north, flowing between the Portneuf Range to the east and the Bannock Range to the west. The river continues northwest through downtown Pocatello. Finally, it joins the Snake River at the southeast part of American Falls Reservoir. This meeting point is about 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Pocatello.

Understanding the River's Watershed and Flow

The Portneuf watershed is a large area of land that drains into the Portneuf River. It covers about 850,290 acres (3,441.0 km2) in southeastern Idaho. This area is surrounded by different mountain ranges. These include Malad Summit to the south, the Bannock Range to the west, the Portneuf Range to the southeast, and the Chesterfield Range to the northeast.

Major Tributaries and Water Flow

Marsh Creek is the most important stream that flows into the Portneuf River. Other smaller creeks in this watershed are Mink, Rapid, Garden, Hawkins, Birch, Dempsey, Pebble, Twentyfourmile, and Toponce creeks. The Chesterfield Reservoir, a body of water in the area, is about 1,236 acres (500 ha) in size. The entire drainage basin of the Portneuf River covers about 1,329 square miles (3,442 km2).

The river's average yearly flow is measured by the USGS. At Tyhee, the average flow is 418 cubic feet per second (11.8 m3/s). The highest flow ever recorded was 1,730 cu ft/s (49.0 m3/s) in one day. The lowest recorded flow was 32 cu ft/s (0.906 m3/s).

A Glimpse into the Portneuf River's Past

The Portneuf River got its name before 1821. It was named by French Canadian voyageurs. These were explorers and traders who worked for the North West Company, a fur trading business based in Montreal.

Historical Routes and Transportation

In the mid-19th century, the Portneuf valley was an important route. It was used by travelers on the Oregon Trail and California Trail. After gold was found in Montana and Idaho, the valley became a key path for moving people and goods by stagecoach. In 1877, the valley was chosen for the route of the Utah and Northern Railway. This was the very first railroad built in Idaho.

Changes to the Portneuf River Environment

The Portneuf River watershed has been greatly changed by human activities. In the early 1960s, there were several big floods. To control future flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers built a concrete channel in 1965. This channel followed the river's path through the west side of Pocatello. This construction drastically changed the river's natural processes.

Nutrient Pollution and Solutions

One common effect of human activity is adding too many nutrients to the water. This happens from both specific sources (like pipes) and widespread sources (like farm runoff). The Portneuf River receives nutrients from intense farming and ranching. It also gets wastewater from Pocatello's treatment facility and a phosphate processing plant. This extra nutrient load causes more plant and animal life to grow in the river.

To help with these issues, the DEQ (Department of Environmental Quality) works with the Soil Conservation Commission and the USDA. They are creating methods called Best Management Practices (BMPs). These practices are designed to reduce nitrogen problems from agriculture and waste. BMPs have been proven to be effective in past projects.

Understanding Carbon Exchange in the River

The exchange of inorganic carbon between the earth and the air in the Portneuf watershed has created deposits of CaCO3. These deposits are known as travertine and tufa. They form because of the unique groundwater and geology of the area. Tufa is a soft, porous CaCO3 deposit found in moving freshwater. Travertine is similar but forms in warmer waters.

The formation of tufa is complex. It involves water dissolving minerals, becoming full of them, moving underground, coming to the surface, and then the minerals forming solid deposits. Both tufa and travertine are found in the Portneuf watershed. Several processes control how CaCO3 forms in natural water systems. These include chemical, physical, and biological processes.

How Chemical Processes Affect Deposits

Calcium carbonate formations are common where rainwater (meteoric waters) picks up calcium carbonate from rocks underground. This happens when the water resurfaces and then the calcite minerals form again. The Portneuf watershed has thick layers of limestone and dolomite rocks, mostly from the ancient Paleozoic era.

Water becomes rich in CaCO3 when it mixes with CO2 from the atmosphere or from soil. This CO2 makes the groundwater more acidic, which helps dissolve carbonate rocks. When the water comes back to the surface, it is exposed to the air. The water tries to balance its CO2 levels, causing calcite to form. This happens through a chemical reaction: Ca+2 + 2HCO− ⇔ CO2↑ + H2O+ CaCO3↓. Many springs in the area, especially near Lava Hot Springs, emerge from these carbonate-rich mountains.

How Physical Processes Affect Deposits

The physical features of the river also play a role in tufa formation. In the area around Lava Hot Springs, the Portneuf River has many small rapids and some larger waterfalls. This fast, turbulent water and increased surface area cause CO2 to escape from the water. This makes the water even more saturated with CaCO3, leading to more mineral deposits. This phenomenon is seen in many places around the world where waterfalls create tufa.

How Living Things Affect Deposits

Living organisms also help tufa form. Algae and mosses, along with other plants and some insects, can trap tiny mineral particles. These trapped particles act as starting points for more mineral deposits to build up. Also, plants that perform photosynthesis remove CO2 from the water. This further concentrates the Ca2+ and CO32−, which encourages more mineral formation.

The Portneuf River in this section has a lot of plant life. This is partly due to the nutrients it picks up from farmland. Also, warm water inputs keep the stream from getting too cold in winter. A study in 1972 showed that tufa and travertine deposits filled the gaps in the river's rocky bottom. This affected some burrowing organisms and how nutrients moved through the system.

In summary, tufa forms in the Portneuf River due to four main things working together:

- Water dissolving limestone rocks.

- CO2 escaping from turbulent water.

- Photosynthetic plants removing CO2 from the water.

- Living things trapping CaCO3 particles.

The way these different processes interact is complex, but they all contribute to the unique mineral formations in the Portneuf River.

See also

In Spanish: Río Portneuf para niños

In Spanish: Río Portneuf para niños