Rafael Caldera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rafael Caldera

|

|

|---|---|

Caldera in 1979

|

|

| President of Venezuela | |

| In office 2 February 1994 – 2 February 1999 |

|

| Preceded by | Ramón José Velásquez |

| Succeeded by | Hugo Chávez |

| In office 11 March 1969 – 11 March 1974 |

|

| Preceded by | Raúl Leoni |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Andrés Pérez |

| Senator for Life | |

| In office 11 March 1974 – 2 February 1994 |

|

| In office 2 February 1999 – 20 December 1999 |

|

| President of the Chamber of Deputies of the Congress of Venezuela | |

| In office 1959–1962 |

|

| Succeeded by | Manuel Vicente Ledezma |

| Solicitor General of Venezuela | |

| In office 26 October 1945 – 13 April 1946 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Rafael Antonio Caldera Rodríguez

24 January 1916 San Felipe, Venezuela |

| Died | 24 December 2009 (aged 93) Caracas, Venezuela |

| Resting place | East Cemetery (Venezuela) |

| Political party | COPEI (1946–1993) National Convergence (1993–2009) |

| Spouse | Alicia Pietri Montemayor |

| Children | 6 |

| Alma mater | Central University of Venezuela |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website: http://www.rafaelcaldera.com |

Rafael Antonio Caldera Rodríguez (born January 24, 1916 – died December 24, 2009) was a Venezuelan politician. He was elected President of Venezuela twice. He served two five-year terms, from 1969 to 1974 and again from 1994 to 1999. This made him the longest-serving democratically elected leader in Venezuela during the 20th century. His first term was special because it was the first time power was peacefully given to the opposition party in Venezuela's history.

Many people see Caldera as one of the key people who helped create Venezuela's democratic system. He also played a big part in writing the 1961 Constitution. He was a leader in the Christian Democratic movement in Latin America. Caldera helped Venezuela have a long period of civilian democratic rule. This was important for a country that had a history of political violence and military leaders. His leadership helped Venezuela become known as a stable democracy in Latin America during the second half of the 20th century.

After finishing his law and political science studies in 1939, Caldera began a 70-year career. He was involved in politics, intellectual work, and teaching.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Rafael Caldera Rodriguez was born on January 24, 1916, in San Felipe, Venezuela. His mother passed away when he was two and a half years old. After that, his aunt, María Eva Rodríguez Rivero, and her husband, Tomás Liscano Giménez, raised him.

Caldera went to elementary school in his hometown of San Felipe. Later, he attended the San Ignacio de Loyola school in Caracas. He finished high school there at age fifteen. The next year, he started studying law at the Central University of Venezuela.

As a young university student, Caldera showed great intelligence. At nineteen, he published his first book, Andres Bello. This book was a deep study of the life and works of Andrés Bello, a famous Venezuelan writer and thinker. The book won an award in 1935 and is still an important resource for studying Bello's work.

A year later, Venezuelan President López Contreras noticed Caldera's newspaper articles about workers' rights. He appointed the twenty-year-old Caldera as deputy director of the new National Labor Office. In this role, Caldera helped write Venezuela's first Labor Law. This law was used for over fifty years.

During his university years, Caldera was active in student politics. He joined the Venezuelan Federation of Students (FEV). However, he bravely left this group when its leaders called for changes against religious groups. In 1936, Caldera started the National Student Union (UNE). This group was the beginning of the Christian Democratic movement in Venezuela.

Political Career

Early Years in Politics (1939–1969)

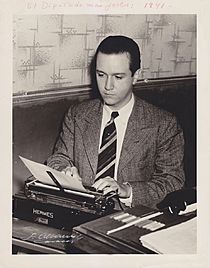

After university, Caldera started a political group called National Action. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for his home state of Yaracuy in January 1941. He was only twenty-five years old.

As a congressman, he spoke out against a border treaty with Colombia. He also helped debate changes to the Constitution and new labor laws. In October 1945, he became Solicitor General. This happened after a new government took power.

In January 1946, Caldera helped create COPEI. This was a Christian Democratic Party that became one of Venezuela's two largest political parties. COPEI believed in democracy, different viewpoints, and social reform. Four months later, Caldera resigned from his job. He did this to protest attacks on members of his new party.

In 1946, he was elected to the National Constituent Assembly. This group was tasked with writing a new Constitution. Venezuelans admired Caldera's speaking skills. People could listen to his speeches on the radio. He spoke about workers' rights, private property, religious freedom, and the need for direct elections.

In the 1947 elections, at age 31, he ran for president for the first time. He traveled around the country to share his party's ideas. He lost to Rómulo Gallegos. Caldera was also elected to Congress. However, his term was cut short when Gallegos was removed from power in November 1948.

During the military rule of Colonel Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–1958), Caldera was arrested several times. He was also removed from his teaching job at Central University of Venezuela. In 1955, a bomb was thrown into his home. In 1957, he was put in solitary confinement. This happened because Pérez Jiménez thought Caldera would be the main candidate for the opposition in the upcoming election. With Caldera imprisoned, Pérez Jiménez changed the election into a vote to keep himself in power.

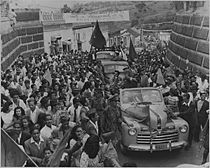

In January 1958, Caldera was exiled. He went to New York City and met with other Venezuelan leaders. His exile lasted only a few days. Marcos Pérez Jiménez was removed from power on January 23, 1958. When Caldera returned to Venezuela, he and two other leaders signed the Puntofijo Pact. This agreement was signed at Caldera's home.

The Puntofijo Pact was a promise by major political parties to build and protect democratic institutions. It aimed to support democracy, respect elections, and keep politics peaceful. This pact became the basis for the longest period of democratic rule in Venezuela (1958–1999).

In the 1958 presidential election, Caldera ran but lost to Rómulo Betancourt. Caldera was then elected President of the Venezuelan Chamber of Deputies. In this role, he helped write the new 1961 Constitution. This Constitution was Venezuela's most successful and long-lasting. For four decades, Venezuela became a stable democracy with peaceful transfers of power.

Caldera ran for president again in 1963 and came in second. He then became president of international Christian Democratic organizations. In December 1968, Caldera ran for president for the third time. He won with 29.1 percent of the vote.

Caldera became president on March 11, 1969. For the first time in Venezuela's history, power was transferred peacefully from the ruling party to the opposition. It was also the first time a party won power without using violence.

First Term as President (1969–1974)

One of the most important things Caldera did during his first presidency was a policy called "pacification." This policy allowed armed groups to stop fighting and join politics peacefully. This helped end ten years of guerrilla warfare in the country.

Caldera also changed Venezuela's foreign policy. He reopened relations with the Soviet Union and other socialist countries. He also improved ties with South American nations that had military governments. This policy was called "pluralistic solidarity."

Caldera took advantage of changes in the international oil market. He increased taxes on oil production and made the gas industry state-owned. He also passed strict laws for U.S. oil companies in Venezuela. In 1971, he raised the oil profit tax to 70 percent. He also passed a law that said all oil company assets would go to the state when their agreements ended. This prepared the way for the government to take over the oil industry.

During his visit to the U.S. in 1970, Caldera got a promise from President Nixon to buy more Venezuelan oil. He spoke to the U.S. Congress and urged Americans to change their approach to Latin America. He said that good relations could not happen if they kept lowering prices for Latin American goods while raising prices for goods Venezuela had to import.

Caldera's main goals at home were education, housing, and infrastructure. He greatly increased the number of schools and universities. New universities built during his time include Simón Bolívar University and Simón Rodríguez. In 1970, he took action at the Central University of Venezuela to restore peace after student protests. Once calm returned, the university regained its independence.

During his first presidency, over 291,000 new homes were built. Many important public buildings and infrastructure projects were also completed. These included the Poliedro de Caracas (a large arena), new ministry buildings, and hospitals. Major highways and airports were also built or improved.

International Leadership and Senate Years (1974–1993)

After his first term as president, Caldera continued his academic and political work. He served in the Venezuelan Senate for life, as was allowed for former presidents under the 1961 Constitution.

During this time, Caldera held important positions in international organizations. He was praised for helping keep democracy stable in Latin America. He served as President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union from 1979 to 1982. In 1979, he led the World Congress of Agrarian Reform and Rural Development.

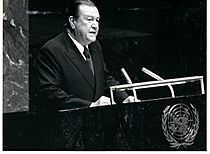

A year later, Caldera led the committee that prepared an international agreement to create the University for Peace. The United Nations General Assembly approved this in 1980. In 1987, Pope John Paul II invited Caldera to speak about social justice.

A main topic in his speeches during these years was finding solutions to the debt crisis affecting many developing countries. He spoke about the unfairness of poor countries having to carry the heavy burden of debt.

As a Senator, Caldera spoke only on important national issues. As the "architect" of the 1961 Constitution, he was often asked to defend its principles. He gave speeches celebrating its 15th and 25th anniversaries. In 1985, he led a commission to reform the Labor Law. This new law was passed in 1990.

In 1989, Caldera led a commission to reform the Constitution. Their project was presented in 1992 but did not get enough support. This project included changes to the justice system and ways for citizens to participate more in democracy. Later events showed how important it was that this reform was not passed.

Caldera gave important speeches in 1989 after unrest in Caracas and in 1992 after a failed military coup. He spoke about the deep problems in the country and how people were losing faith in democracy. He urged students to reject violence and find solutions within democratic principles.

The 1961 Constitution did not allow former presidents to run again until ten years after leaving office. In 1983, Caldera was able to run again but lost the election. In 1993, Caldera ran for president as an independent candidate. He had the support of a new party, National Convergence, and other small parties. Caldera won the presidency. Like his first term, he had to govern with an opposition majority in Congress.

Second Term as President (1994–1999)

Caldera's second term faced big challenges. These included a sharp drop in oil prices, an economic slowdown, high inflation, and a huge banking crisis. The government had to cut its budget and reform tax laws. In 1994, a major bank failed, and the government had to step in. More banks failed, costing the government a lot of money.

In 1996, Caldera started a new economic plan called Agenda Venezuela. This plan increased fuel prices, changed interest rates, and removed price controls on most goods. In 1997, the economy grew, and inflation was cut in half. However, the 1997 Asian financial crisis caused oil prices to fall very low, forcing more budget cuts.

A notable achievement was an agreement between labor unions, businesses, and the government on labor benefits and pensions. This agreement came after ten years of talks.

Fighting corruption was a key goal in Caldera's second term. In 1996, the Organization of American States (OAS) adopted the Inter-American Convention against Corruption. This was often called the Caldera Convention because he was a driving force behind it.

Despite budget limits, Caldera's government completed major infrastructure projects. These included water dams, an aqueduct, and parts of major highways. Line 3 of the Caracas Metro was also finished.

At the start of his second term, Caldera pardoned the military officers involved in the failed coups of 1992. This was meant to calm the military. Many people later questioned this decision, especially after Hugo Chávez, one of the pardoned officers, became popular and won the 1998 presidential election.

Political Ideas

Caldera was a pioneer in bringing Christian Democracy to Latin America. He explained that Christian Democrats see democracy through Christian beliefs. For Caldera, Christian Democracy was a different political choice from both pure capitalism and Marxist socialism. He did not agree with Marxist ideas of class struggle. However, he also believed that capitalism without social protections could lead to an unfair society.

Caldera wrote many books and speeches about Christian Democratic ideas. These included Ideario: La Democracia Cristiana en América Latina (1970) and Especificidad de la Democracia Cristiana (1972). His book Especificidad de la Democracia Cristiana has been translated into several languages. In this book, Caldera described a type of democracy that values individuals, different viewpoints, community, and participation.

This idea of democracy, Caldera explained, is based on Christian beliefs. These include the importance of spiritual values, ethics in politics, human dignity, the common good, and improving society. Caldera also wrote about human development, the value of work, the social role of property, the role of the state, and social justice for all groups. He saw these ideas as a commitment to social justice, inspired by Catholic social teaching.

Caldera's idea of "international social justice" was a unique contribution to Christian Democratic thought.

Caldera's ideas on international social justice slowly influenced the Catholic Church's social teachings. This began with Pope John XXIII's encyclical Mater et Magistra. Eventually, the term itself was used in official Vatican documents.

Intellectual and Academic Life

Caldera was known as a very principled and legally minded president. He was a learned man, a skilled writer, and a great speaker. Even though he rarely left Venezuela for long, he spoke English, French, and Italian fluently. He also knew German and Portuguese well.

He was a full professor of Labor Law and Juridical Sociology at the Central University of Venezuela and Andrés Bello Catholic University. He taught almost continuously from 1943 to 1968. Throughout his life, Caldera received honorary degrees and professorships from many universities around the world. These included universities in Belgium, Italy, Israel, the United States, China, and France. However, the honor he valued most was being named Honorary Professor by his own university, Central University of Venezuela, in 1976.

In 1953, Caldera was elected to the Venezuelan National Academy of Political and Social Sciences. In 1967, he was elected to the Venezuelan National Academy of Language. He spoke about language as a way to connect people in Latin America.

Caldera always had a passion for the Venezuelan writer Andrés Bello. Besides his early book on Bello, he wrote many essays and chapters about him. He also wrote a lot about important people and events in Venezuela's history. His book Bolivar siempre is a collection of essays about the ideas of Simón Bolívar.

Caldera also wrote about the connection between faith and public service. These writings help us understand his strong commitment to his political and intellectual work. Important texts include La Hora de Emaús (1956) and "Jacques Maritain: Fe en Dios y en el pueblo" (1980).

Later Years and Death

After his second presidency, Caldera returned to his home. He was known for living simply and avoiding luxuries. He was seen as an honest public servant in a country where corruption was common. In 1999, when President Hugo Chávez called for a new assembly to write a constitution, Caldera protested. He believed it violated the 1961 Constitution.

In 1999, Caldera published his last book, De Carabobo a Puntofijo: Los Causahabientes. This book tells the political history of Venezuela from 1830 to 1958. In the end of the book, Caldera shared a message of hope. He said that Venezuelans learned to live in freedom, and any political plan that ignores this will fail.

Caldera suffered from Parkinson's disease and slowly withdrew from public life. He passed away at his home on Christmas Eve 2009.

He was a family man and a devoted Catholic. He married Alicia Pietri Montemayor in 1941. They had six children: Mireya, Rafael Tomás, Juan José, Alicia Helena, Cecilia, and Andrés. At the time of his death, they had twelve grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. Mrs. Caldera passed away a little over a year after her husband, in 2011.

Works

- Andrés Bello (1935)

- Derecho del trabajo (1939)

- El Bloque Latinoamericano (1961)

- Moldes para la fragua (1962)

- Democracia Cristiana y Desarrollo (1964)

- Ideario. La democracia cristiana en América Latina (1970)

- Especificidad de la democracia cristiana (1972)

- Temas de sociología venezolana (1973)

- Justicia social internacional y Nacionalismo latinoamericano (1973)

- La nacionalización del petróleo (1975)

- Reflexiones de la Rábida (1976)

- Parlamento mundial: una voz latinoamericana (1984)

- Bolívar siempre (1987)

- Los causahabientes, de Carabobo a Puntofijo (1999)

Rafael Caldera Library

- La Venezuela civil, constructores de la república (2014)

- Los desafíos a la gobernabilidad democrática (2014)

- Justicia Social Internacional (2014)

- Frente a Chávez (2015)

- Andrés Bello (2015)

- Moldes para la fragua. Nueva Serie (2016)

- Ganar la patria (2016)

- De Carabobo a Puntofijo (2017)

- Derecho al Trabajo (2017)

Honors

Selected Honors in Venezuela

- Order "Libertador" (Collar).

- Order "Francisco de Miranda" (Brilliant).

- Order "Andres Bello" (Collar).

- Order "José María Vargas" (Central University of Venezuela).

- Medal "Antonio José de Sucre".

- Order "Estrella de Carabobo", Venezuelan Army.

Selected Honors from Latin American Countries

Argentina: Collar Order of the Liberator General San Martín.

Argentina: Collar Order of the Liberator General San Martín. Bolivia: Great Collar Order of the Condor of the Andes.

Bolivia: Great Collar Order of the Condor of the Andes. Brazil: Great Collar Order of the Southern Cross.

Brazil: Great Collar Order of the Southern Cross. Peru: Great Brilliant Cross Order of the Sun of Peru.

Peru: Great Brilliant Cross Order of the Sun of Peru. Colombia: Great Collar Order of Boyaca.

Colombia: Great Collar Order of Boyaca. Colombia: Collar "Orden Nacional de Miguel Antonio Caro y Rufino José Cuervo".

Colombia: Collar "Orden Nacional de Miguel Antonio Caro y Rufino José Cuervo". Chile: Order Grade Great Official "Simon Bolívar".

Chile: Order Grade Great Official "Simon Bolívar". Ecuador: Great Collar "Orden Nacional al Mérito".

Ecuador: Great Collar "Orden Nacional al Mérito". Paraguay: Collar "Orden Mariscal Francisco Solano López".

Paraguay: Collar "Orden Mariscal Francisco Solano López". Mexico: Collar Order of the Aztec Eagle.

Mexico: Collar Order of the Aztec Eagle. El Salvador: Great Extraodriary Cross Order of José Matías Delgado.

El Salvador: Great Extraodriary Cross Order of José Matías Delgado. Dominican Republic: Order of Christopher Columbus.

Dominican Republic: Order of Christopher Columbus. Uruguay: Medal of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay.

Uruguay: Medal of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay.

Selected Honors from European Countries

Vatican City: Grand Cross of the Pian Order.

Vatican City: Grand Cross of the Pian Order. Netherlands: Orde van de Nederlandse Leeuw.

Netherlands: Orde van de Nederlandse Leeuw. Netherlands: Saint Gregorio Magno Magna Cross.

Netherlands: Saint Gregorio Magno Magna Cross. Romania: Star Order of the Socialist Republic of Romania.

Romania: Star Order of the Socialist Republic of Romania. Spain: Collar of the Order "Isabel La Católica".

Spain: Collar of the Order "Isabel La Católica". Spain: Great Military Cross of Order of Charles III.

Spain: Great Military Cross of Order of Charles III. Rome: Order "Cavaliere di Gran Croce".

Rome: Order "Cavaliere di Gran Croce". Lithuania: Order of Vytautas the Great

Lithuania: Order of Vytautas the Great Portugal: Great Collar of the Infante Dom Henrique of the Government of Portugal.

Portugal: Great Collar of the Infante Dom Henrique of the Government of Portugal. France: Great Cross Legion of Honour of the French Republic.

France: Great Cross Legion of Honour of the French Republic.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rafael Caldera para niños

In Spanish: Rafael Caldera para niños

- Presidents of Venezuela

- List of Venezuelans