Red knot facts for kids

The red knot or just knot (Calidris canutus) is a medium-sized shorebird that lives in coastal areas. These amazing birds breed in the cold tundra and Arctic Cordillera regions of northern Canada, Europe, and Russia. They are one of the largest members of the Calidris family of sandpipers. There are six different types, or subspecies, of red knots.

Red knots eat different foods depending on the season. When they are breeding, they prefer to eat arthropods and insect larvae. At other times, they eat hard-shelled molluscs like clams and snails. Red knots from North America fly to coastal areas in Europe and South America for winter. Birds from Europe and Asia spend their winters in Africa, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand. When they are not breeding, these birds gather in huge flocks.

Quick facts for kids Red knot |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Calidris canutus rufa, breeding plumage | |

|

|

| Non-breeding plumage | |

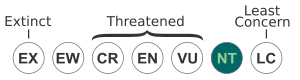

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Calidris |

| Species: |

C. canutus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Calidris canutus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

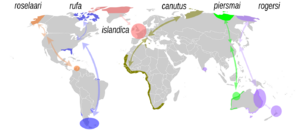

| Distribution and migration routes of the six subspecies of the red knot | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Contents

Understanding Red Knot Names and Types

The red knot was first described by a scientist named Carl Linnaeus in 1758. He called it Tringa canutus. One idea is that the bird's name comes from King Cnut the Great. The story says King Cnut tried to command the tide, and red knots often look for food along the tide line. However, there is no real proof for this idea. Another thought is that the name "knot" sounds like the bird's grunting call.

Scientists group animals into different families. The red knot and the great knot were once the only two birds in the Calidris group. Later, many other sandpiper species were added. Scientists now think the closest relative to the two knot species is the surfbird.

Different Types of Red Knots

There are six recognized subspecies of red knots. They vary slightly in size and where they live:

- C. c. roselaari (largest)

- C. c. rufa

- C. c. canutus

- C. c. islandica

- C. c. rogersi

- C. c. piersmai (smallest)

Amazing Red Knot Migrations

Red knots live all around the world in the high Arctic during their breeding season. Then, they fly to coasts everywhere, from 50° North to 58° South. The red knot has one of the longest migrations of any bird. Each year, it travels more than 9,000 miles (14,000 km) from the Arctic to the southern tip of South America. Then, it flies all the way back!

The exact paths and winter homes for each subspecies are still being studied. For example, the C. c. canutus subspecies breeds in Russia and flies to Western Europe and then to western and southern Africa. The C. c. rogersi subspecies breeds in eastern Siberia and spends winter in eastern Australia and New Zealand.

Birds that spend winter in West Africa usually look for food in a small area of about 2 to 16 square kilometers (0.8 to 6.2 sq mi). They stay at one roosting spot for several months. In other places, like the Wadden Sea, they might change roosting spots every week. Their feeding area can be as large as 800 square kilometers (300 sq mi) in a week.

One famous red knot, known as B95 or Moonbird, is from the C. c. rufa subspecies. This male bird is well-known among people who work to protect birds because he lived for a very long time. He was at least 20 years old when he was last seen in 2014.

What Red Knots Look Like

An adult red knot is the second largest Calidris sandpiper. It is about 23 to 26 centimeters (9.1 to 10.2 in) long. Its wingspan is about 47 to 53 centimeters (19 to 21 in). Its body shape is typical for its group, with a small head and eyes, a short neck, and a slightly pointed beak that is about the same length as its head. It has short, dark legs and a thin, dark bill.

In winter, the bird's feathers are a plain pale grey. Both male and female birds look similar during this time. In the breeding season, their feathers become mottled grey on top. Their face, throat, and chest turn a cinnamon color, and their lower belly is light. Female birds in breeding plumage look similar to males, but their colors are a bit lighter.

When red knots fly, they are easy to spot because of their large size, a white bar on their wings, and a grey rump and tail. When they are looking for food, their short, dark green legs make them look like they are 'low to the ground'. When a single bird is feeding, it usually doesn't make much noise. But when they fly in a flock, they make a low, single sound like "knutt." When they are migrating, they make a two-part sound like "knuup-knuup."

Red Knot Breeding and Life Cycle

Red knots breed in the moist tundra from June to August. The male bird's display song sounds like a fluty "poor-me." During this display, the male flies high in circles, beating his wings quickly. Then, he tumbles to the ground with his wings held up. Both male and female birds incubate the eggs. However, the female leaves the nest after the eggs hatch, and the male takes care of the young birds.

Young red knots have special lines and brown feathers during their first year. The weight of a red knot can be between 100 and 200 grams (3.5 and 7.1 oz). Red knots can double their weight before they migrate. This is because they need a lot of energy for their long journeys. Like many migratory birds, they also make their digestive organs smaller before migration. This helps them save energy.

What Red Knots Eat

When red knots are in their breeding areas, they mostly eat spiders, other arthropods, and insect larvae. They pick these foods from the surface. When they are in their wintering or migration areas, they eat many kinds of hard-shelled prey. This includes bivalves like mussels, gastropods (snails), and small crabs. They swallow these whole, and their strong stomach crushes them.

When feeding in muddy areas during winter or migration, red knots use their beaks to feel for prey hidden in the mud. They poke their beaks into the mud as they walk along the shore. When the tide goes out, they might peck at the surface. In soft mud, they can push their bill about 1 centimeter (0.4 in) deep into the ground. On European coasts, they prefer to eat a type of mollusc called Macoma. They swallow these whole and break them down in their gizzard.

In Delaware Bay, red knots eat large numbers of horseshoe crab eggs. These eggs are a rich and easy-to-digest food source. The horseshoe crabs lay their eggs just as the birds arrive in spring. Red knots can find molluscs buried under wet sand. They sense changes in water pressure using special cells in their bill.

Red Knots and Horseshoe Crabs

Red knots are known as "longest-distance migrants in the animal kingdom." They rely heavily on the same stopping places each year to refuel their bodies during their long journeys. Red knots travel in large flocks, flying about 9,300 miles (15,000 km) from south to north each spring. They repeat this trip in reverse every autumn. They spend the northern hemisphere winters in Tierra del Fuego, South America. Their migration routes lead them to breeding spots on islands and mainland areas above the Arctic Circle during the short arctic summer.

These long trips are broken into several parts, each about 1,500 miles (2,400 km) long. Each part ends at a "staging area" that they visit every year. The Delaware Bay is a very important rest stop for the red knot. Here, they get most of the energy they need by eating lots of horseshoe crab eggs. The relationship between red knots and horseshoe crabs is very close. The birds arrive just when the horseshoe crabs lay their eggs in Delaware Bay.

Why Horseshoe Crab Eggs Are So Important

Before their long migration, red knots go through many changes to prepare their bodies. Their flight muscles get bigger, while their leg muscles get smaller. Their stomach and gizzard also get smaller, but their fat increases by more than 50 percent. They arrive at their stopover sites very thin. Since their gizzard is smaller for travel, they eat fewer hard foods. Instead, they prefer the soft and nutritious horseshoe crab eggs.

Because the birds' migration is timed with the release of these eggs, the eggs are easy to find and eat. This saves the birds a lot of energy. Red knots can double their body weight during their 10–14 day stay at these stopover sites. This is from constantly eating food to build up enough body fat for the rest of their journey. The large number of horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay makes it the most important stopover habitat for red knots. It supports an estimated 50 to 80 percent of all migrating rufa red knots each year.

The health of the horseshoe crab population is very important for the red knot population. In the early 1900s, horseshoe crabs were harvested for fertilizer and animal feed. Today, they are harvested for bait by fishing companies. These activities caused horseshoe crab populations to drop. As a result, red knot numbers in Tierra del Fuego (winter) and Delaware Bay (spring) fell by about 75 percent from the 1980s to the 2000s.

To help, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission set rules for harvesting crabs. They also created a large protected area for horseshoe crabs. These efforts have helped reduce the use of horseshoe crabs as bait. This has led to a stabilization in red knot populations.

Red Knot Status and Threats

The red knot lives across a very large area, estimated to be between 100,000 and 1,000,000 square kilometers (39,000 and 386,000 sq mi). There are about 1.1 million red knots in total. Scientists do not believe the species is declining fast enough to be considered at high risk of extinction. So, it is currently listed as "least concern" by the IUCN Red List. However, some local populations have declined. For example, digging up mudflats for edible cockles led to fewer islandica red knots spending winter in the Dutch Wadden Sea. The quality of food at their migratory stopover sites is very important for their migration.

The red knot is one of the species protected by the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). This agreement means countries that sign it must protect these birds and their habitats.

Dangers to Red Knots

Red knot populations are greatly affected by climate change. This is because their breeding habitats in the middle and high Arctic are changing. Coastal areas where red knots breed and spend winter are most affected by climate change. Their nesting sites are usually on open ground in the tundra near water. Male knots prepare several nest spots on "normally dry, stony areas of tundra in upland areas, often near ridges and not far from wetlands."

Because of sea level rise, coastal erosion, and warming temperatures, the ideal breeding habitats for red knots are being destroyed. As Arctic breeding grounds continue to warm, red knots have become smaller. Birds born in warmer years have less chance of survival. Also, their wintering areas in the tropics have become more stable. This has led to birds with shorter beaks. Shorter beaks make it harder for knots to reach their main food sources, like deeply buried molluscs. This means less food and more energy spent trying to get it.

Over-harvesting of horseshoe crabs and climate change are big threats to red knot populations. While climate change is a difficult problem to solve quickly, limiting horseshoe crab harvesting and reducing human disturbance at knot feeding and breeding sites are effective ways to help protect these birds.

Helping Red Knots Survive

In 2003, scientists thought that the American subspecies, rufa, might disappear as early as 2010 due to its decline. However, as of 2011, the subspecies was still alive. In New Jersey, state and local groups are working to protect these birds. They are limiting horseshoe crab harvesting and restricting access to beaches. In Delaware, a two-year ban on harvesting horseshoe crabs was put in place. Although a judge later overturned it, a male-only harvest has been in place in recent years.

In late 2014, the rufa red knot was listed as a federally threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act. This is the second most serious status a subspecies can get. This decision came after many years of environmental groups asking for protection. The reasons for listing the rufa red knot included habitat damage, loss of important food supplies, and threats from climate change and sea level rise.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Correlimos gordo para niños

In Spanish: Correlimos gordo para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |