Redstone Coke Oven Historic District facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Redstone Coke Oven Historic District

|

|

View south to Chair Mountain past remaining ovens, 2010

|

|

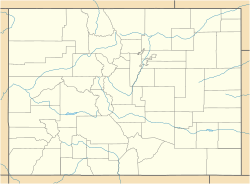

| Location | Redstone, CO |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Aspen |

| Area | 4 acres (1.6 ha) |

| Built | 1899 |

| Architect | Colorado Fuel and Iron |

| MPS | Historic Resources of Redstone |

| NRHP reference No. | 89002385 |

| Added to NRHP | February 7, 1990 |

The Redstone Coke Oven Historic District is a special place near Redstone, United States. It's located where State Highway 133 meets Chair Mountain Stables Road. This district protects old coke ovens built in the late 1800s. The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company built these ovens. In 1990, this area became a historic district. It was then added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Two hundred ovens were built here. This was because the coal in the nearby mountains was perfect for making coke. Coke is a very pure fuel made from coal. At their busiest, these ovens made almost 6 million tons of coke each year! Building these ovens helped start the modern town of Redstone. Not many coke ovens like these are left in the Western U.S.. These ovens are the only things left from what was once Colorado's biggest coke-making operation.

The ovens were not used much after about ten years. This happened when the mines closed. During World War II, their metal supports were taken away for scrap metal. Later, some young people, sometimes called hippies, lived in the ovens. They were looking for a different way of life. At one point, there was a plan to tear down some ovens to build a gas station. Because of this, Pitkin County bought the land in the mid-2000s. Since then, some of the ovens have been restored.

Contents

What Are the Redstone Coke Ovens Like?

The 90 remaining coke ovens form a long curve. They stretch about 600 feet (180 meters). This area covers about 4 acres (1.6 hectares). The ovens are on the west side of Highway 133. They are south of Coal Creek. You can find a small parking area and a sign with information there. The ovens are the main historic part of this district.

Most of the ovens are beehive ovens. They are made of stone with round tops. These tops are covered with hard brown earth. Some ovens still look like they did when they were new. Many others have slowly fallen apart over the years. Four of them have been fixed to look like they did originally.

There's a group of ovens in the middle. These are just north of the parking area. They are inside a stone retaining wall built in the mid-1900s. Because of this wall, these specific ovens are not considered part of the historic district. Wooden fences keep visitors from getting too close to the ovens.

History of the Redstone Coke Ovens

The story of the coke ovens is closely linked to the story of Redstone. The ovens started working when the town was at its busiest. They shut down less than ten years later and were never used again. For much of the 20th century, they were left to decay. Redstone itself almost became a ghost town. A hundred years after they were built, as Redstone began to grow again, the ovens were restored. They became a historic attraction.

Early Days in the Crystal River Valley

The Ute people lived in the Crystal Valley for a long time. They didn't meet Europeans until the late 1700s. By the 1830s, traders and fur trappers were in the area. In the 1840s, John C. Frémont led the first American trips to the valley.

In 1860, people looked for gold here but didn't find any. They named Mount Sopris after their leader. After the American Civil War, the Utes gave up some land. The government wanted people to settle here to use the rich mineral resources. In 1873, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden explored the area. He named many mountains and streams. He also thought the Crystal Valley had a lot of coal.

Building the Mines and Ovens

In 1880, the Ute people moved to reservations. This opened the area for more settlers. People came looking for all kinds of minerals. In 1882, a man named John Cleveland Osgood visited the area. He was looking for coal for a railroad company. He found the coal in the Crystal River Valley was perfect for making coke. He bought land there.

In 1883, Osgood started the Colorado Fuel Company. This company would supply coal to railroads. He and his partners later planned to build a toll road and a railroad. This would make the valley easier to reach. In 1892, Osgood's company merged with a rival. They became Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I). This company became the biggest coal company in the West.

Osgood planned to build a mining town called Coalbasin. It would be high up the Coal Creek valley. The coal there was very pure. A narrow gauge railway would carry the coal 12 miles (19 km) down to Redstone. In Redstone, the coal would be turned into coke. It could also be moved to larger trains. A financial crisis in 1893 delayed these plans.

Busy Years and Then Closure

By the end of 1899, 249 ovens were built. This was the biggest coke-making place in Colorado. Many workers came from Eastern Europe. By 1902, the ovens had made almost 5.7 million tons of coke. Osgood also built the village of Redstone. He wanted workers to have good homes. He also built a large estate nearby, which is now known as Osgood Castle.

The workers often went on strike. This caused problems for CF&I. By 1903, rich investors like John D. Rockefeller took control of CF&I. It became too expensive to ship coke from the Crystal River Valley to CF&I's steel plant in Pueblo. So, in 1909, all mining and coke-making stopped. Redstone became almost empty. Osgood tried to turn the area into a resort later, but he died in 1925. His plans didn't work out because of the Great Depression.

Saving the Ovens: Neglect and Restoration

By the start of World War II, only 14 people lived in Redstone. During the war, the metal supports from the ovens were taken for scrap metal. This made the ovens weaker. In 1953, some ovens were made stronger with a stone retaining wall. This happened when another company started mining coal again.

Other ovens slowly decayed. But they were still strong enough not to fall apart. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, many young people, sometimes called countercultural youth, moved to the Colorado mountains. They wanted to live closer to nature. Some came to Redstone. A few even used the ovens as places to live for a while.

Eventually, these young people left or found other homes. People sometimes took bricks and stones from the ovens for small projects. Even after the ovens were listed as historic, this happened. A big threat came at the end of the 1900s. The company that owned the land went bankrupt. There was a plan to build a convenience store and gas station right in the middle of the ovens.

Local people wanted to save the ovens. They called the ovens "the soul of Redstone." In 2003, a group called the Aspen Valley Land Trust bought the property. A year later, they sold it to the local historical society. The historical society then gave the land to Pitkin County. The county helped pay for the land. This meant the 14 acres (5.7 hectares) with the ovens were finally protected.

Later, the county started paying for restoration work. A plan was made to rebuild part of the original loading area for the ovens. In 2009, this plan won an award. Work began in 2011. The county got $800,000 from different sources.

To make the ovens stable, all plants around them will be removed. The stone retaining wall will be partly rebuilt. Four of the ovens will be fully restored. They will look just like they did originally. They could even be used again, except for the mortar not being heat-resistant enough. Another 56 ovens will be made stable but not rebuilt. The rest will be left as they are. This will show how time has affected them. Workers have found old items inside the ovens. These might be from the original mining days or the hippie years.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |