Regulamentul Organic facts for kids

Regulamentul Organic (meaning Organic Regulation) was a very important set of laws, almost like a constitution. It was put in place by the Russian Empire in 1831–1832 in two regions called Moldavia and Wallachia. These two regions later became the country of Romania.

The document kept some traditional ways of governing, like having local rulers called hospodars. It also created a shared Russian protectorate, which meant Russia had a lot of control over these lands until 1854. The Regulamentul itself stayed in effect until 1858. Even though it was a bit old-fashioned in some ways, it also brought many new changes. These changes helped the local society become more like Western Europe. For the first time, the Regulamentul gave Moldavia and Wallachia a common system of government.

Contents

Why the Regulamentul Organic Was Created

The regions of Moldavia and Wallachia had been under the control of the Ottoman Empire for a long time. They had to pay tribute to the Ottomans. However, Russia often got involved in their affairs, especially since the early 1700s. Russia, being an Orthodox empire, felt a connection to the local people who were also Orthodox.

Ottoman and Russian Influence

The Ottomans tried to keep tight control by appointing Greek rulers called Phanariotes. But Russia kept challenging this control. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 gave Russia the right to protect Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Russia used this right to interfere in Moldavia and Wallachia. For example, Russia helped rulers who had lost Ottoman approval.

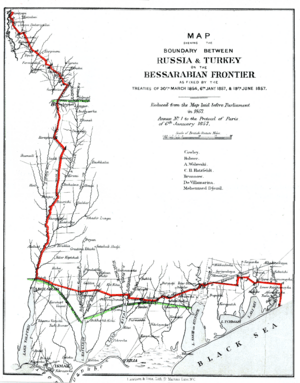

In 1812, Russia even took over a part of Moldavia called Bessarabia. Even with new Greek officials, powerful local noble families, called boyars, kept their control. They often asked both the Ottoman Empire and Russia for help to keep their special rights.

European Consuls and Local Uprisings

In the late 1700s, European countries like Russia, Austria, and France opened consulates in the region. These offices watched what was happening and sometimes gave special protection to certain individuals. These people were known as sudiți, meaning "subjects" of a foreign power.

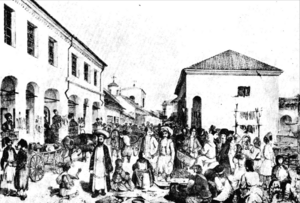

A big event happened in 1821. Greek nationalists started a rebellion in the Balkans to gain independence from the Ottomans. This led to a Greek secret society, the Filiki Eteria, taking over Moldavia and Wallachia. In Wallachia, a local leader named Tudor Vladimirescu also started a rebellion against the Greek rulers. He was supported by some boyars and initially by Russia. However, Russia later withdrew its support. Vladimirescu was eventually killed, and the Ottomans invaded to crush the Greek rebellion. After this, the boyars managed to convince the Ottomans to end the system of Greek Phanariote rulers.

Agreements and Russian Control

After the Greek rulers were gone, local princes were chosen. Ioniță Sandu Sturdza became Prince of Moldavia, and Grigore IV Ghica became Prince of Wallachia. But their rule was short. Russia intervened again during the Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829, and removed them.

Akkerman Convention

On October 7, 1826, the Ottoman Empire and Russia signed the Akkerman Convention. This agreement was important because it officially ended the rule of Greek Phanariote princes. New princes would be elected by local councils for seven-year terms. The two regions also gained the right to trade freely, especially grain. This was a big change from the old rules where the Ottomans controlled most trade. The convention also mentioned new "Statutes" or laws that would be created.

Russian Occupation and the Treaty of Adrianople

Russian troops entered Moldavia and Wallachia in April 1828. This military presence lasted for a long time. The war also brought terrible diseases like bubonic plague and cholera, which killed many people. The Russian army also took a lot of resources from the local economy. For example, they took cattle, and Wallachia had to borrow a lot of money to support the Russian troops. Many people became unhappy with the Russian rule.

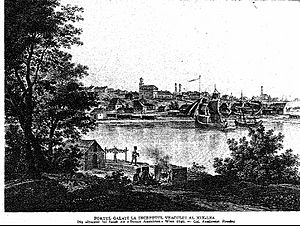

The Treaty of Adrianople, signed on September 14, 1829, confirmed Russia's victory. It also strengthened Russia's control over Moldavia and Wallachia. Wallachia gained control over important ports on the Danube River like Brăila, Giurgiu, and Turnu Măgurele. Free trade and navigation on the Danube and Black Sea were officially allowed. This helped the regions connect more directly with European traders.

Russia continued to occupy Moldavia and Wallachia until the Ottomans paid their war debts. Russian governors were put in charge to supervise the creation of the new "Statutes."

Pavel Kiselyov and the New Laws

The time after the Treaty of Adrianople was difficult for Moldavia and Wallachia. Russia took their money, and the Russian governor, Pyotr Zheltukhin, interfered a lot. He even removed boyars who disagreed with him. Many people felt that Russia's actions were unfair.

The third and last Russian governor was Pavel Kiselyov. He took office on October 19, 1829. Kiselyov faced big challenges like the ongoing plague and cholera outbreaks, and the threat of famine. He dealt with these by setting up quarantines and bringing in grain. His time as governor, until April 1, 1834, brought many important reforms.

Adopting the Regulamentul Organic

The Regulamentul Organic was officially adopted in Wallachia on July 13, 1831, and in Moldavia on January 13, 1832. Even though the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II had not yet approved it, Kiselyov started enforcing it right away.

The final version of the document created a government with a clear separation of power. This meant that different parts of the government had different jobs.

- The hospodars (princes) were the executive branch. They were elected for life by a special assembly. They could choose ministers and public officials.

- The National Assembly (Adunarea Obștească) was the legislature. It was controlled by high-ranking boyars.

- The judiciary (courts and judges) was made separate from the hospodars' control for the first time.

New Reforms

The Regulament also brought a new tax reform. It introduced a poll tax (a tax per family) and removed most other taxes. Annual state budgets were created and approved by the Assemblies. The princes no longer used their personal money for government expenses; instead, a civil list was set up. New ways of keeping financial records were also introduced.

However, some historians noted that the Regulament mostly helped the boyars. The middle class had little influence, and peasants had almost no say in their own communities. Despite this, many conservative boyars were still worried that Russia might try to take over the regions completely.

Economic Changes

Under Kiselyov's leadership, Moldavia and Wallachia saw many big changes in their economy and society.

Growing Cities and Towns

The number of people in the middle class grew. They benefited from increased trade, which made merchants more important. Traditional guilds (groups of skilled workers) slowly disappeared, leading to a more competitive, capitalist economy.

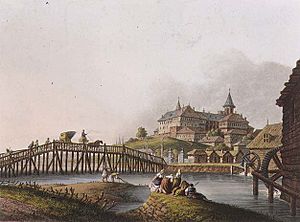

Cities grew very quickly. The population of Bucharest, the capital of Wallachia, was about 70,000 in 1831 and grew to about 120,000 by 1859. Iași, the capital of Moldavia, also grew. Ports like Brăila, Giurgiu, and Galați became rich from the grain trade. Kiselyov focused on developing Bucharest, improving its roads and services. Public works projects expanded transport and communication systems.

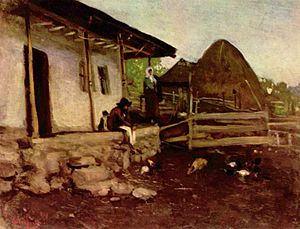

Life in the Countryside

The success of the grain trade was based on rules that limited peasants' rights. Peasants who leased land from boyars could only keep about 70% of their harvest. Boyars could use a third of their land as they wished. Small farms struggled against larger estates. This meant more peasants had to lease land and still owed work to the boyars.

The corvée (forced labor for the lord) was set at up to 12 days a year. However, since pastures were owned by boyars, peasants often had to work more days to use them. Laws were passed to prevent peasants from paying money instead of working, ensuring boyars had enough workers for the growing grain trade.

The Regulament divided peasants into three groups based on their wealth:

- Fruntași (foremost people): Owned 4 working animals and 1 or more cows. They could use about 4 hectares of pasture.

- Mijlocași (middle people): Owned 2 working animals and 1 cow. They could use about 2 hectares of pasture.

- Codași (backward people): Owned no property and were not allowed to use pastures.

The population grew, partly because of better health measures against diseases. More people moved from the countryside to cities. Industrialization was minimal because most money came from agriculture and was reinvested there.

Tensions grew between peasants and landowners. Peasants sometimes resisted through sabotage or violence. In 1831, about 60,000 peasants protested against new rules for joining the army. Russian troops killed about 300 people while putting down the revolt.

Culture and Politics

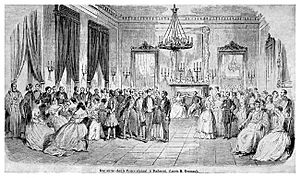

A major cultural change under the Regulament was the rise of Romantic nationalism in Romania, often linked with French culture. Modernization led to a rebirth of intellectual life. The idea of "nation" started to include more than just the boyars. Many privileged people began to care about the problems faced by peasants.

Nationalism and Education

Nationalist ideas included focusing on the Latin origin of Romanians and using the old name "Dacia" for the whole region. This showed a growing desire for all Romanians to be united. There were also fake documents that claimed to be old agreements between the Ottoman Empire and the Romanian regions, trying to prove their ancient rights.

Education became less dominated by the Greek language after 1821. Teachers like Gheorghe Lazăr and Gheorghe Asachi tried to introduce teaching in the Romanian language. The Regulament led to new schools being created. Many teachers came from Transylvania, a region then under Austrian rule. They often disagreed with adopting too much French culture. The Moldavian Regulation even stated that all teaching should be in the Moldavian language.

Small national armies, sometimes called "militias," were also created under Russian supervision. These armies helped boost national pride.

Western Influence

Romanian society quickly became more like Western Europe, especially France. This trend started earlier with contacts between the region and France. Many young boyars went to study in Paris. A French-language school opened in Bucharest in 1830. This French influence was very strong.

Challenges to the Regulament

In 1834, Russia and the Ottoman Empire decided to appoint the first two hospodars together, instead of having them elected. This was to ensure the rulers would follow a moderate path and stay loyal. Alexandru II Ghica became Prince of Wallachia, and Mihail Sturdza became Prince of Moldavia. These rulers, known as "statutory reigns," were closely watched by Russian officials. They soon faced strong opposition from the Assemblies and other groups.

The "Additional Article" and Opposition

Russia demanded that the local Assemblies vote for an "Additional Article." This article would prevent any changes to the Regulament without approval from both Istanbul (Ottoman Empire) and Saint Petersburg (Russia). In Wallachia, this caused a big scandal. A nationalist group in the Assembly started working on their own constitution. They wanted to end Russian and Ottoman control and gain independence with support from European powers.

The leader of this movement, Ion Câmpineanu, had connections with other European nationalists. Even though the "Additional Article" was eventually passed, Câmpineanu had to leave the country. Opposition to Ghica's rule then turned into secret groups inspired by Freemasonry and carbonari. Young politicians like Nicolae Bălcescu and Ion Ghica were part of these groups. Many were arrested in 1840.

Because of these problems, the Ottoman Empire and Russia withdrew their support for Ghica in 1842. His successor, Gheorghe Bibescu, was the first and only prince elected by one of the Assemblies. In Moldavia, the situation was calmer, as Sturdza managed to control the opposition while still making reforms.

The Revolutions of 1848

In 1848, revolutions spread across Europe. In Moldavia, a revolution in March 1848 failed, and Russian troops returned. However, Wallachia's revolt was successful. On June 21, the Proclamation of Islaz outlined a new government and land reform, ending all corvée labor. The revolutionaries overthrew Bibescu and set up a temporary government in Bucharest.

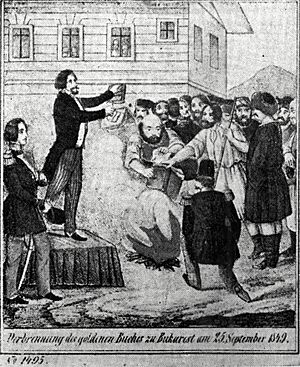

In September, the new government publicly burned the Regulament. They tried to get support from the Ottoman Empire against Russia. But Russian diplomats convinced the Ottoman Sultan to intervene. Russian troops joined the Ottoman occupation of Wallachia. Both occupations lasted until April 1851. In 1849, the two powers signed the Convention of Balta Liman, which gave the Ottoman Sultan the right to appoint hospodars for seven-year terms.

The Crimean War and Its Aftermath

During the Crimean War (1853-1856), Moldavia and Wallachia were taken over by a neutral Austrian administration in September 1854. This was part of an agreement between the Ottoman Empire and Russia. The Austrians stayed until 1857.

Grigore Ghica and Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei returned as rulers in the same year. They completed the last reforms under the Regulament. One of the most important reforms was about Roma slavery. In Moldavia, Roma people were freed on December 22, 1855. In Wallachia, the ban on owning slaves was made by Știrbei on February 20, 1856. Știrbei also worked to improve the lives of peasants by introducing contract-based work on estates.

|