Rohingya people facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,547,778–2,000,000+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,300,000+ (March 2018) | |

| 600,000 (November 2019) | |

| 500,000 (September 2017) | |

| 190,000 (January 2017) | |

| 150,000 (October 2017) | |

| 50,000 (December 2017) | |

| 40,000 (September 2017) | |

| 12,000+ (September 2017) | |

| 5,000 (October 2017) | |

| 3,000 (October 2018) | |

| 3,000 (October 2014) | |

| 1,478 (December 2023) | |

| 300 (May 2018) | |

| 200 (September 2017) | |

| 200 (September 2017) | |

| 107 (December 2017) | |

| 36 (June 2017) | |

| 11 (October 2019) | |

| Languages | |

| Rohingya | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Muslims; minorities of Hindus and Christians | |

The Rohingya people ( Rohingya) are a group of people who mostly follow Islam and live in Rakhine State, Myanmar. They are considered stateless, which means they don't have citizenship in any country. Before 2017, about 1.4 million Rohingya lived in Myanmar. After a difficult period in 2017, over 740,000 Rohingya had to leave their homes and flee to Bangladesh.

Journalists and news reports often call the Rohingya one of the most unfairly treated groups in the world. This is because Myanmar's 1982 nationality law does not give them citizenship. They also face limits on where they can go, what education they can get, and what jobs they can have. Some experts, like Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu, have compared their situation to apartheid, a system of unfair separation.

The Rohingya believe they are native to western Myanmar. They say their history goes back over a thousand years, with influences from Arabs, Mughals, and Portuguese traders. They claim to be descendants of people who lived in the region when it was an independent kingdom.

However, the Myanmar government sees the Rohingya as people who moved from Chittagong in Bangladesh during British rule. They say that any distinct Muslim groups from before colonial times are called Kaman. The government also does not use the term "Rohingya," preferring to call them "Bengali" instead. Rohingya groups and human rights organizations are fighting for their right to have a say in their own future within Myanmar.

There have been several armed conflicts involving the Rohingya since the 1940s. The group has faced military actions in 1978, 1991–1992, 2012, and 2015. A major event happened between 2016 and 2018, when most of the Rohingya in Myanmar were forced to leave the country and go to Bangladesh. By December 2017, about 625,000 Rohingya had crossed into Bangladesh since August 2017.

Before 2015, about 1.1 to 1.3 million Rohingya lived in Myanmar, mostly in northern Rakhine. Since then, over 900,000 Rohingya have become refugees in Bangladesh. Many others have gone to countries like India, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. More than 100,000 Rohingya still in Myanmar live in special camps and are not allowed to leave.

Contents

- Understanding the Name "Rohingya"

- A Look at Rohingya History

- Early Times in Arakan

- How Islam Arrived

- The Kingdom of Mrauk U

- Burmese Takeover

- British Colonial Rule

- After Burma's Independence

- Mayu Frontier District

- Forced Departure of Burmese Indians

- Refugee Crisis of 1978

- 1982 Citizenship Law

- Refugee Crisis of 1991–1992

- Name Change from Arakan to Rakhine State

- Conflict in Arakan

- After 1988 Pro-Democracy Uprising

- Military Governments (1990–2011)

- Where Do Rohingya People Live?

- Rohingya Culture

- Rohingya Language

- Rohingya Religion

- See also

Understanding the Name "Rohingya"

The word "Rohingya" comes from older terms like Rooinga and Rwangya. The Rohingya people call themselves Ruáingga. In the Burmese language, they are called rui hang gya, and in Bengali, they are called Rohingga. The name "Rohingya" might come from Rakhanga or Roshanga, which are words for the state of Arakan. This would mean "inhabitant of Rohang," an old Muslim name for Arakan.

When Was the Term "Rohingya" First Used?

The term "Rohingya" was used before the British took control of India. In 1799, a writer named Francis Buchanan wrote about "Mohammedans" who had lived in Arakan for a long time and called themselves "Rooinga," meaning natives of Arakan. In 1815, Johann Severin Vater listed "Ruinga" as a group with its own language.

In 1936, when Burma was still under British rule, a group called the "Rohingya Jam’iyyat al Ulama" was started in Arakan.

Different Views on the Name

Some historians, like Jacques Leider, say that during British rule, the Rohingya were called "Chittagonians" or "Bengalis." He notes that there isn't a worldwide agreement on using the term "Rohingya." They are sometimes called "Rohingya Muslims" or "Muslim Arakanese." Some people, like anthropologist Christina Fink, see "Rohingya" more as a political term than an ethnic one.

The government of Prime Minister U Nu (1948-1962) used the term "Rohingya" in radio talks to help bring peace. However, the term wasn't widely used until the 1990s.

Today, the use of the name "Rohingya" is a sensitive topic. The Myanmar government refuses to use it. In the 2014 census, the government made the Rohingya identify as "Bengali." Many Rohingya feel that denying their name is like denying their basic rights. The United States embassy in Yangon continues to use the name "Rohingya."

A Look at Rohingya History

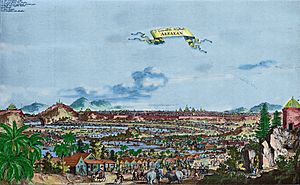

The Rohingya people mainly live in the historic region of Arakan, a coastal area in Southeast Asia.

Early Times in Arakan

It's not fully clear who the first people in Arakan were. Some Burmese stories say the Rakhine have been there since 3000 BCE, but there's no proof from old sites. By the 4th century, Arakan became one of the first kingdoms in Southeast Asia to be influenced by India. Old writings in the region suggest that the first Arakanese states were founded by people from India.

Historian Daniel George Edward Hall said that Burmese people might not have settled in Arakan until the 10th century CE. This means earlier rulers were likely Indian, governing people similar to those in Bengal.

How Islam Arrived

Arakan was an important place for trade and cultural exchange because it was on the Bay of Bengal. Arab traders were in contact with Arakan as early as the 3rd century. The Rohingya people trace their history back to this time.

Some believe that the first Muslim communities in Arakan started in the 7th century. Arab traders were also missionaries and began converting local Buddhist people to Islam around 788 CE. These traders also married local women and settled in Arakan, helping the Muslim population grow. However, other historians disagree, saying that Islam spread to this region much later, mostly with Bengali Muslims from what is now Bangladesh. They also note that the term "Rohingya" doesn't appear in old texts from this period.

The Kingdom of Mrauk U

The Rakhines, a Burmese tribe, started moving into Arakan in the 9th century. They built many cities. In 1406, Burmese forces attacked Rakhine cities. This made Rakhine rulers ask for help from Bengal.

Bengali Muslim settlements in Arakan began around the time of King Min Saw Mon (1430–34) of the Kingdom of Mrauk U. He got his throne back in 1430 with help from the Bengal Sultanate. The Bengalis who came with him settled in the area.

For a short time, Arakan was under Bengal's rule. The Buddhist kings of Arakan even took Islamic titles and used Bengali money. They also hired Muslims for important jobs in the royal government.

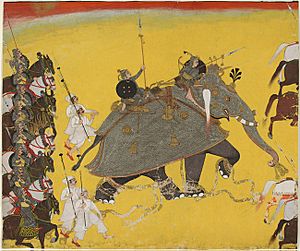

In the 17th century, more people came to Arakan as slaves, brought by Arakanese and Portuguese raiders from Bengal. These slaves included important Mughal nobles. One famous slave was Alaol, a poet.

In 1660, Prince Shah Shuja, a Mughal prince, fled to Arakan with his family. He was given safety by King Sanda Thudhamma. However, the Arakanese king later took Shuja's gold, leading to a fight. Shuja's family was killed, and he might have escaped. Some of his followers stayed and joined the Arakanese army.

In 1666, the Mughal Empire took Chittagong from the Kingdom of Mrauk U.

Burmese Takeover

In 1785, the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma conquered Arakan. About 35,000 people from Rakhine State fled to British Bengal to escape unfair treatment. The Burmese killed many men and sent others to central Burma, leaving Arakan with very few people.

British Colonial Rule

The British encouraged Bengali people from nearby areas to move to Arakan for farm work. There were no strict borders between Bengal and Arakan, so people moved freely. Thousands of Bengalis from Chittagong settled in Arakan looking for jobs. It's not clear if these were new migrants or people returning after being forced out earlier.

By 1911, the Muslim population in Akyab District had grown to 178,647. This was mainly because the British needed cheap labor for rice fields. Many historians believe most Rohingya arrived with the British in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Thant Myint-U, a historian, noted that in the early 1900s, many Indians came to Burma each year. By 1927, 480,000 people arrived in one year. This was a huge number for Burma's total population of 13 million. Indian immigrants became the majority in many large Burmese cities. Burma was part of the British Indian Empire until 1937. Burmese people felt helpless and reacted with strong feelings against Indians.

In the 1931 census, Muslims made up 4% of Burma's population. About 41% of all Muslims in Burma lived in Arakan.

Shipping and Trade

Because of the Arakan Mountains, it was easiest to reach Arakan by sea. The port of Akyab had busy trade with ports in British India and Rangoon. Akyab was a major rice port. Many Indians settled in Akyab and controlled its port and surrounding areas.

World War II and Conflict

During World War II, the Japanese army invaded British-controlled Burma. When the British left, there was a lot of fighting between Arakanese and Muslim villagers. The British gave weapons to Muslims in northern Arakan to create a safe area against the Japanese. This led to violence between groups loyal to the British and those supporting Burmese nationalists.

This period saw strong tensions. Muslims fled from Japanese-controlled areas to British-controlled northern Arakan. Some historians say that Rohingya groups, armed by the British, attacked Arakanese villages instead of fighting the Japanese. In March 1942, Rohingyas killed about 20,000 Arakanese. In return, Rakhines killed about 5,000 Muslims.

About 22,000 Muslims in Arakan crossed into Bengal to escape the violence. Many other groups also left Burma at this time.

Calls for a Muslim Area

During the 1940s, some Rohingya Muslims wanted their region to join East Pakistan. Muslim leaders believed the British had promised them a "Muslim National Area." In 1946, there were calls for the area to join Pakistan or become an independent state. Before Burma's independence in 1948, Muslim leaders asked Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, for help. However, Jinnah reportedly refused to get involved in Burma's affairs.

After Burma's Independence

In 1954, Prime Minister U Nu spoke about the Rohingya Muslims' loyalty to Burma. This is important because today Myanmar denies the term "Rohingya." A special administrative zone called Mayu Frontier Region was set up for the Rohingya-majority area.

However, after the military took control in 1962, the Rohingya's rights were slowly taken away. In 1978, the military government launched an operation that forced 200,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Bangladesh at first refused to let them in, leading to many deaths. After talks, most Rohingya were sent back.

Rohingya in Politics

Before independence, two Rohingya were elected to Burma's assembly in 1947. After independence, M. A. Gaffar asked for "Rohingya" to be recognized as an official ethnic name. In the 1950s, several Rohingya were elected to Parliament, including one of the first female MPs, Zura Begum. Sultan Mahmud, a former politician, became Minister of Health.

The 1962 military coup ended this political system. The 1982 citizenship law later took away citizenship from most Rohingya.

Rohingya leaders supported the 8888 uprising for democracy in 1988. In the 1990 Burmese general election, a Rohingya-led party won four seats. However, the military government banned the party in 1992 and jailed its leaders. Today, there are no Rohingya MPs in Burma, and most Rohingya cannot vote.

Mayu Frontier District

From 1961 to 1964, a separate area called the Mayu Frontier District existed for the Rohingya-majority northern parts of Arakan. It was managed directly by the national government. After the military coup in 1962, the army ran it. In 1974, it became part of Arakan State.

Forced Departure of Burmese Indians

After the 1962 military coup, unfair treatment towards people with Indian ties increased. The military government took over all businesses, including many owned by Burmese Indians. Between 1962 and 1964, 320,000 Burmese Indians were forced to leave the country.

Refugee Crisis of 1978

In 1978, many Rohingya had to flee to Bangladesh because of a military operation. About 200,000 Rohingya sought safety in Cox's Bazar. After talks, most refugees were able to return to Burma with help from the UNHCR.

1982 Citizenship Law

In 1982, Myanmar's citizenship law did not list the Rohingya as one of the 135 "national races" of Burma. This made most Rohingya in their homeland stateless. This law was based on a British survey from 1823. Any group not listed was considered foreign.

Some scholars believe this law was a way for the military to make their anti-Indian and anti-Muslim views into law. They argue that taking away citizenship from the Rohingya has led to much unfair treatment and harm to the group.

Refugee Crisis of 1991–1992

After the 1990 election, the military government began to target political opponents. Military actions against Muslims, who supported democracy, started in Arakan State. The Rohingya political party was banned, and its leaders were jailed.

About 250,000 refugees crossed into Bangladesh. Bangladesh and Burma sent many troops to the border. After talks, an agreement was made for refugees to return to Burma under UNHCR supervision.

Name Change from Arakan to Rakhine State

In 1989, the government officially changed the name of Burma to Myanmar. In the 1990s, they changed the name of Arakan province to Rakhine State. This showed a preference for the Rakhine community, even though Rohingya were a large part of the population. The region had been known as Arakan for centuries.

Refusal to Use "Rohingya"

The term "Rohingya" has been used for a long time. However, since the 1982 citizenship law, Myanmar's governments have strongly refused to use the term. They prefer to call the community "Bengali illegal immigrants." The insulting word kalar is also used against the Rohingya in Myanmar. Myanmar's government often pressures foreign visitors not to use the term "Rohingya."

Conflict in Arakan

The Rakhine people also felt unfairly treated by the Burmese-dominated government. Some Rakhine politicians said they were victims of both "Muslimisation and Burmese chauvinism." The Economist wrote in 2015 that both Burmese and Rakhine groups see themselves as victims, so they have little sympathy for the Rohingya.

After Pakistan refused to take northern Arakan, some Rohingya elders started a Mujahid party in 1947. Their goal was to create an independent Muslim state in Arakan. By the 1950s, they started using the term "Rohingya" to create a distinct identity. General Ne Win carried out military operations against them for two decades. One major operation in 1978 forced many Muslims to flee to Bangladesh.

From 1971 to 1978, Rakhine monks protested to make the government deal with immigration. Ne Win's government asked the UN to help send refugees back. In 1978, Bangladesh protested against Burma for forcing thousands of Muslim citizens out. Burma replied that those expelled were illegal residents from Bangladesh. After talks, Burma agreed to take back 200,000 refugees. However, in 1982, the Burmese government passed the citizenship law, calling the "Bengalis" foreigners.

After 1988 Pro-Democracy Uprising

Since the 1990s, a new "Rohingya" movement has grown. It involves Rohingya living abroad asking for international support, scholars claiming native status, and politicians promoting the term "Rohingya."

Some Rohingya scholars have claimed that Rakhine was an Islamic state for a thousand years, or that Muslims were important figures for Rakhine kings for 350 years. They often say Rohingya came from Arab sailors. These claims have been called "newly invented myths" by other scholars.

This movement has been criticized by ethnic Rakhines and Kamans. Kaman leaders support citizenship for Muslims in northern Rakhine but believe the new movement aims to create a separate Islamic state. Rakhines are more critical, fearing that the Rohingya are part of a large wave of people that will take over Rakhine. However, for many Rohingya, the main goal is simply to gain citizenship. Some moderate Rohingya politicians are willing to use a different name, like "Rakhine Muslims" or "Myanmar Muslims," if it means they get citizenship.

Military Governments (1990–2011)

The military governments that ruled Myanmar for 50 years often used Burmese nationalism and Buddhism to strengthen their power. The US government believes they treated minorities like the Rohingya unfairly. Some Burmese pro-democracy activists do not see the Rohingya as fellow citizens.

Myanmar's governments have been accused of causing riots against minorities like the Rohingya. In the 1990s, over 250,000 Rohingya fled to refugee camps in Bangladesh. By the early 2000s, most were sent back to Myanmar, some against their will. In 2009, a Burmese official called the Rohingya "ugly as ogres" and foreign to Myanmar.

Under the 2008 constitution, the Myanmar military still controls much of the government, including key ministries and 25% of parliament seats.

Where Do Rohingya People Live?

Most people who identify as Rohingya live in the northernmost areas of Arakan, near Bangladesh. In these areas, they make up 80–98% of the population. A typical Rohingya family has four or five children, but some have many more. In 2018, 48,000 Rohingya babies were born in Bangladesh refugee camps.

As of 2014, about 1.3 million Rohingya lived in Myanmar, and an estimated 1 million lived in other countries. They make up about 40% of Rakhine State's total population. As of 2016, the United Nations said that 1 out of every 7 stateless people in the world was Rohingya.

Before 2015, about 1.1 to 1.3 million Rohingya lived in Myanmar. Many have since fled to southeastern Bangladesh, where there are over 900,000 refugees. Others have gone to India, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. More than 100,000 Rohingya in Myanmar live in special camps and are not allowed to leave.

Rohingya Culture

Rohingya culture is similar to other groups in the region. Their clothing is often like what other people in Myanmar wear.

Men wear bazu (long-sleeved shirts) and longgi or doothi (loincloths). Religious scholars might wear kurutha or panjabi (long tops). For special events, Rohingya men sometimes wear taikpon (collarless jackets).

Lucifica is a flat bread that Rohingya eat often. Bola fica is a popular snack made from rice noodles. Betel leaves, called faan, are also popular.

Rohingya Language

The Rohingya language is part of the Indo-Aryan language family. It is related to the Chittagonian language spoken in Bangladesh, which borders Myanmar. While both Rohingya and Chittagonian are related to Bengali, they are not easily understood by Bengali speakers. Rohingya people often do not speak Burmese, which is the main language of Myanmar, and this can make it hard for them to fit in.

Rohingya scholars have written their language using different writing systems, including Arabic, Hanifi, Urdu, Roman, and Burmese alphabets. Hanifi is a new alphabet that uses Arabic letters with some extra letters from Latin and Burmese.

More recently, a Latin alphabet has been created for Rohingya, using all 26 English letters plus two more Latin letters. It also uses special marks over vowels to show different sounds. This alphabet has been recognized by ISO with the code "rhg".

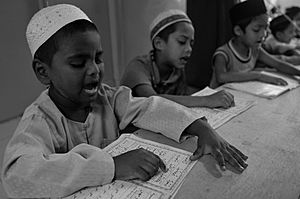

Rohingya Religion

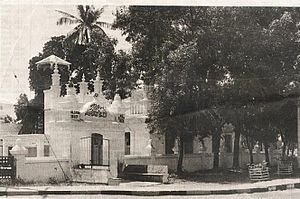

Most Rohingya people practice Islam, often a mix of Sunni Islam and Sufism. There are also smaller groups of Rohingya who practice Hinduism and Christianity. Because Rohingya are not considered citizens in Myanmar, they are not protected from unfair treatment by the government. This means they face challenges in practicing their religion freely.

The government limits their chances for education. As a result, many Rohingya choose to study basic Islamic teachings as their main option. Mosques and madrasas (Islamic schools) are found in most villages. Traditionally, men pray together in groups, while women pray at home.

Muslims in Burma have often faced difficulties building places of worship. In the past, they have also been arrested for teaching and practicing their religious beliefs.

See also

In Spanish: Rohinyá para niños

In Spanish: Rohinyá para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |