Seaplane facts for kids

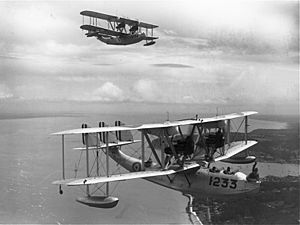

A seaplane is a special kind of airplane that can take off from and land on water. Some seaplanes can also land on regular runways; these are called amphibious aircraft. Seaplanes are usually split into two main types: floatplanes and flying boats. Flying boats are generally much bigger and can carry more weight.

Seaplanes were very popular during and after World War II. However, as more airports were built, their use slowly decreased. Today, seaplanes are used for specific jobs, like dropping water on forest fires, traveling between islands, or reaching places without roads that have many lakes.

Contents

What are the main types of seaplanes?

The word "seaplane" describes two main kinds of aircraft that use water:

- A floatplane has thin floats (like skis) attached under its body. Usually, there are two floats, but sometimes more. Only these floats touch the water, keeping the main body of the plane dry. Floatplanes are often small aircraft. They can't handle big waves, usually only waves smaller than about 12 inches (0.31 meters). The floats make the plane heavier and slower, which means it can't carry as much or fly as fast.

- In a flying boat, the main body of the plane itself acts like a boat hull. It's shaped to move smoothly through the water. Most flying boats have small floats on their wings to help them stay steady. While some small seaplanes are floatplanes, most large seaplanes are flying boats because their big hulls can support their heavy weight.

Sometimes, people use "seaplane" to mean only "floatplane," especially in Britain. But in this article, "seaplane" includes both flying boats and floatplanes.

An amphibious aircraft is a special type of seaplane that can take off and land on both water and land runways. A true seaplane can only use water. There are amphibious flying boats and amphibious floatplanes. Some even have floats that can be pulled up into the plane!

Today, most new seaplanes are smaller, amphibious, and designed as floatplanes.

How did seaplanes develop?

Early seaplane inventors

The idea for a flying machine that could land on water came from Frenchman Alphonse Pénaud in 1876. He even patented a design with a boat-like body and wheels that could be pulled in. However, the first person to actually build a seaplane was Austrian Wilhelm Kress in 1898. His plane, the Drachenflieger, didn't have strong enough engines to take off and later sank.

On June 6, 1905, Gabriel Voisin flew a kite glider with floats on the River Seine after being towed by a boat. He later tried to build a powered floatplane, but it wasn't successful.

Many other inventors in Britain, Australia, France, and the United States also tried to add floats to airplanes.

On March 28, 1910, Frenchman Henri Fabre made the first successful flight of a powered seaplane. His plane, the hydravion, had three floats. Fabre's success inspired others, and he designed floats for many other pilots. The first seaplane competition happened in Monaco in March 1912. This led to the first regular seaplane passenger flights in France later that year. On May 10, 1912, Glenn L. Martin flew his own seaplane in California, setting new distance and time records.

In 1911−12, François Denhaut built the first seaplane where the main body was shaped like a boat hull. It flew successfully on April 13, 1912.

American inventor Glenn Curtiss also worked on floatplanes. In 1911, he made the first flights of an amphibious aircraft (one that could land on both land and water). From 1912, he started building "flying-boats," like his 1913 Model E and Model F. In February 1911, the United States Navy started testing Curtiss's planes for landing on and taking off from ships.

In Britain, Captain Edward Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius experimented with flying from water on Windermere, England's largest lake. In November 1911, Wakefield's pilot successfully took off and landed on the lake, flying at about 50 feet (15 meters).

A seaplane was even used in the Balkan Wars in 1913. A Greek "Astra Hydravion" flew over the Turkish fleet and dropped four bombs.

The birth of the seaplane industry

In 1913, the Daily Mail newspaper offered a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean. American businessman Rodman Wanamaker wanted an American plane to win this prize. He hired the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to build such an aircraft. Curtiss worked with John Cyril Porte, a retired British Navy officer and pilot. They focused on making boat-like hulls that could handle water well, which was key for long flights.

Around the same time, the Benoist XIV biplane flying boats started the world's first airline service using heavier-than-air aircraft in the United States.

In Britain, the boat-building company J. Samuel White also started making flying boats. In 1913, the "Bat Boat" was built. It was an amphibious aircraft that could land on both land and water. It won a prize for its ability to make several return flights over five miles.

Wanamaker's project with Curtiss led to the America flying boat. It was much larger than earlier designs so it could carry enough fuel to fly 1,100 miles (1,800 km). During testing, the plane's nose would try to go underwater when speeding up on the water. To fix this, Curtiss added special "sponsons" (like small underwater pontoons) to the sides of the hull. These sponsons became a common feature on flying boats later on. With this problem solved, they planned to fly across the Atlantic on August 5, 1914.

Seaplanes in World War I

The plans for the Atlantic flight were stopped by the start of World War I. John Cyril Porte returned to the British Navy. He convinced the Navy that flying boats were important and was put in charge of the naval air station at Felixstowe in 1915. Porte got the Navy to buy the America and other similar planes from Curtiss. These planes were called Americas in the Royal Navy. Their engines were replaced with more powerful ones.

The Curtiss H-4 planes had problems: they weren't powerful enough, their hulls were weak, and they were hard to handle on water. One pilot even called them "comic machines."

At Felixstowe, Porte greatly improved flying boat design. He created a new hull shape with a special "Felixstowe notch." This notch helped the plane break free from the water's surface more easily when taking off. This made flying boats much safer and more reliable. This "notch" later became a "step" in the hull, which is still a feature of flying boat hulls and seaplane floats today.

Porte then designed a new hull for the larger Curtiss H-12 flying boat. This new design, called the Felixstowe F.2, first flew in July 1916. It was much better than the original Curtiss plane. About 100 F.2A planes were built by the end of World War I and used for patrols.

Later, the Felixstowe F.3 was made. It was bigger and could fly further and carry more bombs, but it was less agile. About 100 F.3s were made. The Felixstowe F.5 tried to combine the best parts of the F.2 and F.3.

Porte's last design was the huge, five-engined Felixstowe Fury triplane.

The F.2, F.3, and F.5 flying boats were used a lot by the British Navy to patrol coasts and hunt for German U-boats (submarines). In 1918, British flying boats even fought German seaplanes, shooting down several. After this, British flying boats were painted with "dazzle camouflage" to make them harder to identify in battle.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company also kept improving its designs. They built the Felixstowe F.5 under license as the Curtiss F5L, using American engines.

In Italy, several seaplanes were developed. The Macchi M.5 was very fast and agile, even matching land-based fighter planes. Two hundred forty-four were built and used by the Italian, US Navy, and US Marine Corps airmen.

German company Hansa-Brandenburg also built successful flying boats, like the Hansa-Brandenburg W.12 floatplane fighter.

Between the World Wars

In September 1919, the British company Supermarine started the world's first flying-boat airline service from Woolston to Le Havre in France, but it didn't last long.

A Curtiss NC-4 became the first airplane to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1919, making several stops. Only one of the four planes that tried completed the journey.

In 1923, the first successful commercial flying-boat service started, with flights to the Channel Islands. The British government later decided to combine several aviation companies to form Imperial Airways of London (IAL). IAL became Britain's main international airline, using flying boats like the Short S.8 Calcutta to connect Britain with South Africa and India.

In 1928, four Supermarine Southampton flying boats from the RAF flew to Melbourne, Australia. This flight showed that flying boats could reliably travel long distances.

In the 1930s, flying boats made it possible to have regular air travel between the U.S. and Europe, and to new places in South America, Africa, and Asia. Places like Foynes, Ireland, and Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador, were important stops for early transatlantic flights. Since many areas didn't have land airports, flying boats could stop at small rivers, lakes, or coastal stations to refuel. The Pan Am Boeing 314 "Clipper" flying boats became famous for connecting people to exciting new destinations.

By 1931, mail from Australia could reach Britain in just 16 days, less than half the time it took by ship. Qantas and IAL teamed up to create Qantas Empire Airways, offering a new ten-day service between Rose Bay, New South Wales, (near Sydney) and Southampton. This service was so popular that they soon needed bigger planes.

The British government asked Short Brothers to design a large, long-range plane for IAL in 1933. Qantas bought six of these Short Empire flying boats.

The race to deliver mail quickly led to some interesting designs. One unique Short Empire flying boat was the "Maia and Mercury." The "Mercury" (a smaller floatplane) was carried on top of "Maia" (a modified Short Empire flying boat). The larger Maia would take off with the Mercury, which was too heavy to take off on its own. This allowed the Mercury to carry enough fuel for a direct flight across the Atlantic with mail. However, this system was too complicated.

Sir Alan Cobham invented a way to refuel planes in the air in the 1930s. This meant Short Empire flying boats could take off with less fuel and then get more fuel while flying over Foynes, allowing them to make direct transatlantic flights.

The German Dornier Do X flying boat looked different from British and U.S. planes. It had wing-like parts called sponsons coming from its body to keep it stable on water, so it didn't need floats on its wings. This idea was first used by Claude Dornier during World War I. The huge Do X had 12 engines and could carry 170 people. It flew across the Atlantic to the Americas in 1929. It was the biggest flying boat of its time, but it wasn't powerful enough and couldn't fly very high. Only three were built.

Seaplanes in World War II

The military importance of flying boats was well known, and many countries used them when the war started. They were used for many jobs, like hunting submarines, rescuing people from the sea, and spotting for battleships. Planes like the PBY Catalina, Short Sunderland, and Grumman Goose rescued downed pilots and acted as scout planes over the huge areas of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. They also sank many submarines and found enemy ships. In May 1941, a PBY Catalina found the German battleship Bismarck.

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238. It was also the heaviest plane to fly during World War II and the biggest aircraft built by any of the Axis Powers.

In November 1939, Imperial Airways was reorganized into three companies, including British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC). BOAC continued to operate flying boat services from safer harbors during the war. When Italy joined the war in June 1940, the Mediterranean Sea was closed to Allied planes. So, BOAC and Qantas used Short Empire flying boats to operate the "Horseshoe Route" between Durban and Sydney.

The Martin Company built the prototype XPB2M Mars flying boat, based on their PBM Mariner patrol bomber. It was tested between 1941 and 1943. The Navy converted the Mars into a transport plane. Five of these large Mars aircraft were delivered by 1947.

After World War II

After World War II, the use of flying boats quickly decreased. This was because many land-based runways were built during the war, making it easier for regular planes to land. Also, land-based planes became faster and could fly further, making flying boats less competitive for commercial travel. They couldn't compete with new jet aircraft like the de Havilland Comet and Boeing 707.

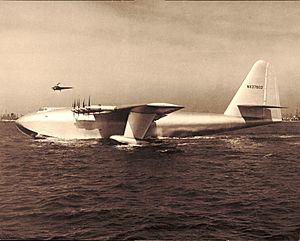

The Hughes H-4 Hercules, developed in the U.S. during the war, was even bigger than the BV 238. It didn't fly until 1947. This huge 180-ton plane, nicknamed the "Spruce Goose," was the largest flying boat ever to fly. It made a short hop of about a mile (1.6 km) at 70 feet (21 meters) above the water. After the war, there was no longer a need for such a large transport plane.

In 1944, the Royal Air Force started developing a small jet-powered flying boat for air defense in the Pacific. The Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 prototype first flew in 1947 and performed well. However, by the end of the war, aircraft that could take off from aircraft carriers were much better, so the SR.A/1 was no longer needed.

During the Berlin Blockade (1948-1949), ten Sunderlands and two Hythes were used to carry goods to isolated Berlin, landing on a lake. The Sunderlands were especially good for carrying salt because their bodies were already protected from saltwater corrosion. This was the only time flying boats were used for operations in central Europe.

The U.S. Navy continued to use flying boats, like the Martin P5M Marlin, until the early 1970s. The Navy even built a jet-powered seaplane bomber, the Martin Seamaster.

BOAC stopped its flying boat services from Southampton in November 1950.

Against the trend, Aquila Airways was started in 1948 to fly to places that land-based planes couldn't reach. This company used Short S.25 and Short S.45 flying boats from Southampton to places like Madeira, Las Palmas, and Lisbon. Aquila also flew troops on special trips. The airline stopped flying on September 30, 1958.

The very advanced Saunders-Roe Princess first flew in 1952. Even though it was a great flying boat, none were sold. Of the three Princesses built, two never flew, and all were scrapped in 1967.

Ansett Australia operated a flying-boat service from Rose Bay to Lord Howe Island until 1974.

On December 18, 1990, Pilot Tom Casey completed the first round-the-world flight in a floatplane, using only water landings. He flew a Cessna 206 called Liberty II.

How are seaplanes used today?

Many modern civilian airplanes have floatplane versions. These are often used as transport planes to lakes and other remote areas. While some companies still build floatplanes from scratch, many are modified versions of land planes. Some older flying boats are still used for fighting fires by dropping water. Chalk's Ocean Airways used Grumman Mallards for passenger service until a crash in 2005, which was linked to maintenance issues.

Purely water-based seaplanes have mostly been replaced by amphibious aircraft, which are more flexible.

Seaplanes need calm water to take off and land. Like other aircraft, they have trouble in bad weather. The size of waves a plane can handle depends on its size, hull design, and weight. This makes them less stable in rough conditions, limiting the days they can operate. Flying boats can usually handle rougher water and are more stable than floatplanes when on the water.

Seaplanes are also used in remote areas like the wilderness of Alaska and Canada, especially where there are many lakes for easy takeoffs and landings. They might be used for special trips, regular flights, or by people living in those areas for personal travel. Some seaplane companies offer services between islands, such as in the Caribbean Sea or the Maldives.

See also

In Spanish: Hidroavión para niños

In Spanish: Hidroavión para niños