Sherman's March to the Sea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sherman's March to the Sea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Sherman's March to the Sea, Alexander Hay Ritchie |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Tennessee Army of Georgia |

Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 62,204 | 12,466 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| more than 1,300 casualties | around 2,300 casualties | ||||||

| Economic loss: $100 million | |||||||

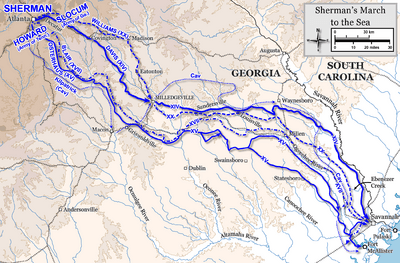

Sherman's March to the Sea, also called the Savannah Campaign, was a major military event during the American Civil War. It happened in Georgia from November 15 to December 21, 1864. William Tecumseh Sherman, a top general in the Union Army, led this campaign.

The march started after Union forces had captured Atlanta. It ended when Sherman's troops took control of the port city of Savannah. During the march, Sherman's army used a "scorched earth" tactic. This meant they destroyed military targets, factories, roads, and even some private property. Their goal was to weaken the Confederacy's ability to fight. This action greatly hurt the Confederacy and helped bring the war to an end.

Sherman's decision to move deep into enemy land without regular supply lines was very unusual. Some historians see this campaign as an early example of modern warfare or total war. After this march, Sherman's army continued north into the Carolinas Campaign. The part of the march through South Carolina was even more destructive. This was because many Union soldiers blamed South Carolina for starting the Civil War.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "March to the Sea" comes from a poem. It was written by S. H. M. Byers in late 1864. Byers was a Union prisoner of war held in South Carolina. While imprisoned, he wrote a poem called "Sherman's March to the Sea." Another prisoner, W. O. Rockwell, set it to music.

When Byers was freed, he gave his poem to General Sherman. Sherman was very touched by it. He promoted Byers to his staff, and they became lifelong friends. The poem gave the campaign its famous name. A musical version of the poem became very popular with Sherman's army and the public.

Why the March Happened

Military Goals

Sherman's "March to the Sea" followed his successful Atlanta Campaign in 1864. General Sherman and the Union Army's commander, Ulysses S. Grant, believed the Civil War would only end if the Confederacy's ability to fight was completely broken. Sherman planned an operation that involved "scorched earth" tactics. This meant destroying things that could help the enemy.

Sherman knew that taking food from local farms would hurt the feelings of the people living there. This was part of his plan to weaken their will to fight. Another goal was to help Grant's armies in Virginia. Grant was stuck fighting Robert E. Lee's army near Petersburg, Virginia. By marching into Georgia, Sherman hoped to put more pressure on Lee. He also wanted to stop Confederate troops from going to help Lee.

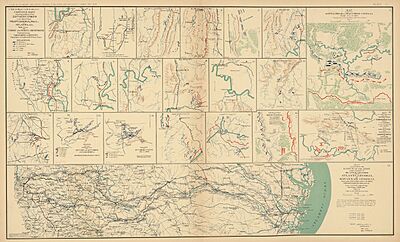

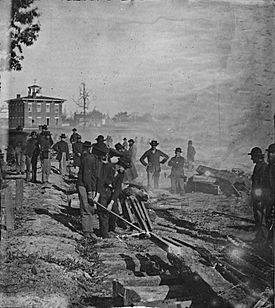

The campaign was designed so Sherman's army would not need regular supplies. They would "live off the land" after their first 20 days of food ran out. Soldiers called "bummers" would find food from local farms. They would also destroy railroads, factories, and farms in Georgia. Sherman used information from the 1860 census to guide his troops. He wanted to go through areas where they could find the most food. The twisted and broken railroad tracks left behind were called "Sherman's neckties."

Sherman's Orders

Sherman knew his army would be out of touch with the North. So, he gave clear orders for how the campaign should be carried out. These were called Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 120. Here are some important parts:

- Getting Supplies: The army would take food and supplies from the land. Each group of soldiers would have a party to gather corn, meat, vegetables, and other needed items. They always aimed to keep at least ten days of food in their wagons.

- Respecting Homes: Soldiers were not allowed to enter people's homes or cause damage. But during breaks, they could gather vegetables and bring in livestock near their camps.

- Destroying Property: Only high-ranking commanders could order the destruction of mills, houses, or cotton gins. If the army was not bothered by enemy fighters, property should not be destroyed. But if local people attacked them or blocked roads, then commanders could order more destruction.

- Taking Animals: Cavalry and artillery could take horses, mules, and wagons from people. They were told to take more from rich people, who were usually against the Union, and less from poor or friendly people.

- Treating People: Soldiers were told to be polite and not use bad language. They could give written notes about what they took. They also tried to leave enough food for each family to survive.

- African Americans: Able-bodied African Americans who could help the army could come along. But commanders had to remember that feeding the soldiers was the most important task.

Who Fought in the March

Union Army

General Sherman did not use all his troops for this campaign. A Confederate general, John Bell Hood, was threatening another Union area. So, Sherman sent two armies to deal with Hood. This left Sherman's main army mostly unopposed in Georgia.

Before the march, Sherman made sure his soldiers were in top shape. Doctors checked every man to make sure they were strong and healthy. Only the "best fighting material" was allowed to go. Most of the soldiers were experienced fighters from earlier battles.

Sherman also cut down on the supplies the army carried. He wanted them to live off the land as much as possible. Each group of soldiers had a small supply train. Each regiment had only one wagon and one ambulance. This helped the army move faster.

Sherman's force had about 62,000 men. This included 55,000 infantry (foot soldiers), 5,000 cavalry (horse soldiers), and 2,000 artillerymen with 64 cannons. They were split into two main groups:

- The right wing was the Army of the Tennessee, led by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard.

- The left wing was the Army of Georgia, led by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum.

- A cavalry group, led by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, supported both wings.

A British historian once called Sherman's army "probably the finest army of military 'workmen' the modern world has seen." After surrendering to Sherman, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston said, "there has been no such army since the days of Julius Caesar."

Confederate Army

The Confederate forces opposing Sherman were much smaller. General John Bell Hood had taken most of Georgia's troops to Tennessee. This left only about 13,000 men in Georgia. Most of these were Georgia militia, made up of young boys and older men. There were also about 10,000 cavalry troopers. The Confederate War Department tried to bring in more men, but they never had more than 13,000 soldiers to fight Sherman.

The March Begins

Both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant had doubts about Sherman's plan. But Grant trusted Sherman and gave him the go-ahead on November 2, 1864. The march, which covered about 300 miles (480 km), began on November 15.

Sherman later wrote about leaving Atlanta:

... We rode out of Atlanta by the Decatur road... and reaching the hill, just outside of the old rebel works, we naturally paused to look back upon the scenes of our past battles... Behind us lay Atlanta, smouldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city... Some band, by accident, struck up the anthem of "John Brown's Body"; the men caught up the strain, and never before or since have I heard the chorus of "Glory, glory, hallelujah!" done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.

—William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, Chapter 21

Sherman's personal guards were from the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment. This unit was made up of Southerners who stayed loyal to the Union.

The two parts of Sherman's army tried to trick the Confederates. They wanted to hide where they were going. The Confederates couldn't tell if Sherman was heading for Macon, Augusta, or Savannah.

The first real fight happened at the Battle of Griswoldville on November 22. Confederate cavalry attacked, but Union soldiers fought them off. The Confederates lost about 1,100 men, while the Union lost only 100.

Meanwhile, Sherman's other group reached Milledgeville, the state capital. The governor and state lawmakers quickly left. On November 23, Union troops captured the city. They even held a fake meeting in the capitol building, joking about Georgia rejoining the Union.

There were several smaller fights as the march continued. Union cavalry made a fake move toward Augusta. They then planned to destroy a railroad bridge and free prisoners of war. However, they learned the prisoners had been moved.

On November 30, another Union force tried to help Sherman near Savannah. They fought a battle at Battle of Honey Hill against Georgia militia. The militia held their ground, and the Union troops pulled back after losing about 650 men.

Reaching Savannah

Sherman's armies reached the edge of Savannah on December 10. But Confederate General William J. Hardee had dug in his 10,000 men. He had also flooded the surrounding rice fields. This left only narrow paths to reach the city.

Sherman couldn't connect with the U.S. Navy as planned. So, he sent cavalry to Fort McAllister, which guarded the Ogeechee River. He hoped to clear the way and get supplies from Navy ships. On December 13, Union soldiers stormed Fort McAllister in the Battle of Fort McAllister. They captured it in just 15 minutes. Some Union soldiers were hurt by "torpedoes," which were early forms of land mines.

Now Sherman could get supplies and cannons from the Navy. On December 17, he sent a message to Hardee in Savannah. He demanded the city surrender. Sherman warned that if he had to attack, he would use "harshest measures."

Hardee decided not to surrender. Instead, he escaped with his men across the Savannah River on a temporary bridge on December 20. The next morning, Savannah's mayor offered to surrender the city. He asked for a promise that citizens and their property would be protected. Sherman agreed. His troops marched into Savannah that same day.

After the March

Sherman sent a telegram to President Lincoln, saying, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton." Lincoln replied, thanking Sherman for the "great success."

The march created many refugees, especially formerly enslaved people. Sherman issued Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 15, which set aside land for them. This order is often seen as the start of the "40 acres and a mule" promise.

Sherman's army stayed in Savannah for about a month. Soldiers were told to behave well, or they would face harsh punishment. Sherman also helped organize aid for the many refugees in the city. He even sold captured rice to raise money to feed the people of Savannah.

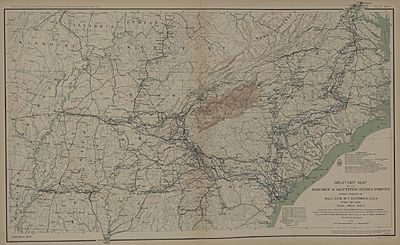

From Savannah, Sherman marched north in the spring for the Carolinas Campaign. His goal was to join his armies with Grant's to fight Robert E. Lee. Sherman's next big action was the capture of Columbia, the capital of South Carolina. After a successful two-month campaign, Sherman accepted the surrender of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina on April 26, 1865.

We are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying papers into the belief that we were being whipped all the time, realized the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience.

Sherman's "scorched earth" tactics have always been a topic of debate. Many people in the Southern United States still dislike Sherman's memory. The opinions of enslaved people about Sherman's army were mixed. Some welcomed him as a liberator and followed his army. Others felt upset because they suffered along with their owners. One Confederate officer thought 10,000 freed slaves followed Sherman's army. Hundreds of them died from hunger or disease along the way.

The March to the Sea caused huge damage to Georgia and the Confederacy. Sherman himself estimated the destruction at $100 million. The army destroyed about 300 miles (480 km) of railroad tracks and many bridges. They took thousands of horses, mules, and cattle. They also destroyed many cotton gins and mills. Historians say Sherman's raid "knocked the Confederate war effort to pieces."

A recent study found that the damage from the March led to a big drop in farming and manufacturing. Some of these effects lasted until 1920.

Legacy and Songs

Union soldiers sang many songs during the March. But one song written afterward became a symbol of the campaign: "Marching Through Georgia." Henry Clay Work wrote it in 1865. The song tells the story from a Union soldier's point of view. It talks about freeing slaves and punishing the Confederacy. Sherman himself came to dislike the song. This was partly because he didn't like to celebrate over a defeated enemy. Also, the song was played almost everywhere he went.

Sadly, hundreds of African Americans drowned trying to cross Ebenezer Creek north of Savannah. They were trying to follow Sherman's army. In 2011, a historical marker was put there to remember them.

Historians still debate whether Sherman's March was "total war." Some have compared his tactics to those used in World War II. Others argue that Sherman's actions were not as harsh or widespread. Some historians use the term "hard war" to describe Sherman's tactics. This helps show the difference between his actions and later "total war" methods.

See also

In Spanish: Marcha de Sherman hacia el mar para niños

In Spanish: Marcha de Sherman hacia el mar para niños

- The March: A Novel (a historical novel from 2005)

- Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 15

- Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 120

- Sherman's March (a 2007 documentary film)

- Western Theater of the American Civil War

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |