Siege of Orléans facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Orléans |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans by Jules Eugène Lenepveu, painted 1886–1890 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

William Glasdale † |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,300 • c. 3,263–3,800 English • 1,500 Burgundians |

6,400 soldiers 3,000 armed citizens |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| More than 4,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

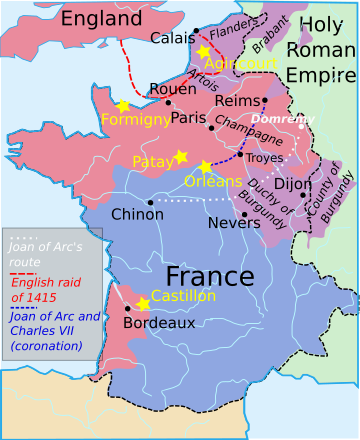

The Siege of Orléans was a major battle during the Hundred Years' War between France and England. It happened from October 12, 1428, to May 8, 1429. This siege was a turning point in the war. It took place when England was at its strongest. But French forces, led by Joan of Arc, pushed them back. After this victory, France started to win back lands that England had taken.

The city of Orléans was very important to both sides. Many people at the time believed that if Orléans fell, the English would conquer all of France. For about six months, the English and their French allies, the Burgundians, seemed close to capturing the city. But the siege ended just nine days after Joan of Arc arrived.

Contents

Background to the Siege

The Hundred Years' War Explained

The Siege of Orléans happened during the Hundred Years' War. This was a long fight over who should be the King of France. The main families fighting were the French royal family and the English royal family. The war began in 1337. England's King Edward III claimed he should be the King of France. He was the son of a French princess, Isabella of France.

After a big win at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, England gained control of much of northern France. In 1420, the Treaty of Troyes was signed. This treaty said that England's King Henry V would rule France. He married Catherine, the daughter of the French King Charles VI. The treaty stated that Henry would become King of France after Charles VI died. This meant that Charles, the son of the French king and the rightful heir (called the Dauphin), was disinherited.

Why Orléans Was Important

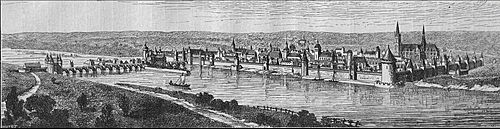

Orléans is located on the Loire River in central France. At the time of the siege, it was the northernmost city still loyal to the French king. The English and their allies, the Burgundians, controlled the rest of northern France, including Paris. Orléans was the last major obstacle. If the English took it, they could easily move into central France. England already controlled France's southwestern coast.

The city was also the capital of the Duchy of Orléans. This made it important in French politics. The Dukes of Orléans led a group called the Armagnacs. They did not accept the Treaty of Troyes. They supported the disinherited Dauphin Charles. The leader of this group, the Duke of Orléans, was a prisoner of the English. He had been captured fourteen years earlier at Agincourt.

In medieval times, if a city surrendered without a fight, its people were treated well. But if a city resisted, it could expect harsh treatment. Mass killings were common in such cases. Orléans was linked to the Armagnac party. This meant it would likely face severe punishment if it fell.

Preparing for the Siege

The War's Situation

After a small conflict in 1425–26, English and Burgundian forces renewed their alliance. They attacked the Dauphin's France again in 1427. The area around Orléans was very important. It controlled the Loire River. It also connected English lands in the west with Burgundian lands in the east. French forces had not been very effective. But they did manage to lift the siege of Montargis in late 1427. This was the first real French success in years. It encouraged small uprisings in English-held areas to the west.

However, the French could not take full advantage of this. This was mainly because the French court was having internal power struggles. The English used this French weakness. They brought in new soldiers from England in early 1428. This force of 2,700 men was led by Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury. He was seen as England's best commander. More soldiers joined from Normandy and Paris. Burgundian allies also joined, making the total force possibly 10,000 men.

In the spring of 1428, the English regent, John, Duke of Bedford, decided to focus English attacks on the west. Their goal was to defeat the remaining French forces and besiege Angers. Orléans was not originally part of this plan. Bedford had even made a deal to leave Orléans alone. But he changed his mind after Salisbury arrived with more soldiers in July 1428. Bedford later wrote that the siege of Orléans was started "God knoweth by what advice." This suggests it was Salisbury's idea.

Salisbury's Approach

From July to October, the Earl of Salisbury moved through the countryside southwest of Paris. He captured several towns. Then, instead of going to Angers, Salisbury turned towards Orléans. He reached the Loire River at Meung-sur-Loire and captured it. He also took the bridge and castle of Beaugency. Salisbury crossed the Loire and approached Orléans from the south. He arrived at Olivet, just south of Orléans, on October 7. Meanwhile, another English group captured towns east of Orléans. Orléans was now surrounded.

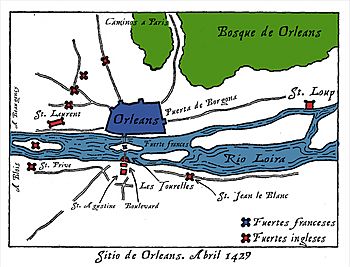

John of Dunois, who was defending Orléans, prepared the city for the siege. He knew the English would attack the long bridge. This bridge connected the south bank of the Loire to the city center on the north bank. At the bridge's southern end was a gatehouse called Les Tourelles. Dunois quickly built a large earthwork fort, called a Boulevart, on the south bank. He put most of his soldiers there to protect the bridge. He also ordered the southern suburbs of Orléans to be emptied. All buildings were torn down so the English could not use them for cover.

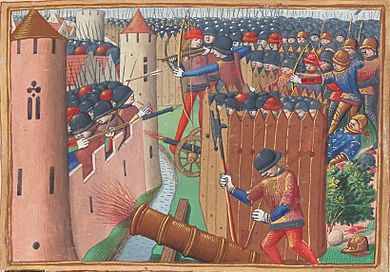

Early Days of the Siege

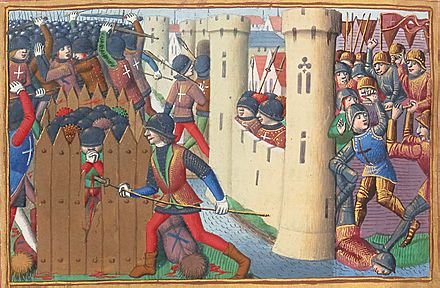

Attack on the Tourelles

The siege officially began on October 12, 1428. Artillery bombardment started on October 17. The English attacked the Boulevart on October 21. But French soldiers fought them off with arrows, hot oil, and quicklime. The English decided not to attack directly again. Instead, they started digging tunnels under the fort. The French dug their own tunnels, set them on fire, and then retreated to the Tourelles on October 23. The Tourelles itself was captured the next day, October 24. The French blew up some parts of the bridge as they left. This stopped the English from following them.

With the Tourelles captured, Orléans seemed lost. But the Marshal de Boussac arrived with many French soldiers. This stopped the English from fixing the bridge and taking Orléans right away. The English faced another problem two days later. The Earl of Salisbury was hit in the face by debris from a cannon shot. He was taken away to recover but died about a week later from his injuries.

Surrounding the City

The pause in English attacks after Salisbury's death gave Orléans time. The citizens destroyed more parts of the bridge. This made a quick repair and attack impossible. The new English commander, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, decided to surround the city. His plan was to starve it into surrender. He did not have enough men to build a continuous wall of trenches. So, he built a series of strongholds, called bastides or outworks. Over the next few months, seven forts were built on the north bank. Four were built on the south bank.

In the winter, about 1,500 Burgundian soldiers arrived to help the English.

Building these forts was difficult. The French soldiers often attacked the builders. They also destroyed other buildings, like churches, in the suburbs. This stopped the English from using them for shelter in winter. By spring 1429, English forts covered only the south and west of the city. The northeast was mostly open. French soldiers could move in and out of the city. But it was very hard to bring in food and supplies.

On the south bank, the main English position was the bridge complex. This included the Tourelles-Boulevart and the now-fortified Augustines monastery. To the east of the bridge was the fort of St. Jean-le-Blanc. To the west was the fort of Champ de St. Privé. On the north bank, the largest English fort was St. Laurent. This was the main center for English operations. Above it were smaller forts like "London" and "Paris." There was a large open area to the northeast. Finally, about 2 km east of the city, was the isolated fort of St. Loup.

Orléans seemed to be in a bad situation. Any help would have to come from Blois, to the southwest. This was exactly where the English had many soldiers. Supply convoys had to take long, dangerous routes to reach the city from the northeast. Few made it through, and the city soon began to run out of food. If Orléans fell, it would be almost impossible for France to get back its northern lands. It would also be very bad for the Dauphin Charles's claim to the crown.

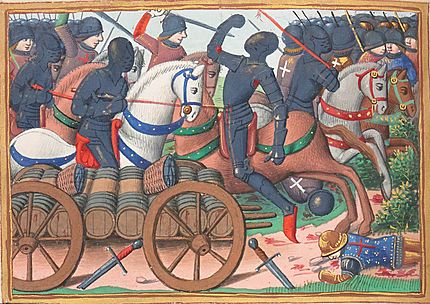

The Battle of the Herrings

The danger to Orléans made the French leaders agree to a temporary truce in October 1428. In early 1429, Charles de Bourbon gathered French and Scottish soldiers in Blois. Their goal was to bring supplies to Orléans. They heard that an English supply convoy was coming from Paris. This convoy was led by Sir John Fastolf. Charles decided to try and stop it. He was joined by soldiers from Orléans led by John of Dunois. They met at Janville. They attacked the English convoy at Rouvray on February 12. This fight is known as the Battle of the Herrings. The convoy was carrying a lot of fish for the upcoming Lent season.

The English knew the French were coming. They formed a defensive circle with their supply wagons. Archers stood around the wagons. Charles ordered the French to hold back and use their cannons. But the Scottish soldiers, led by John Stewart of Darnley, attacked. The French lines hesitated, unsure whether to follow. The English saw their chance. English cavalry rode out of the wagon fort. They quickly defeated the Scots and pushed back the French. Panic spread, and the French retreated. Stewart of Darnley was killed, and John of Dunois was wounded. Fastolf brought the supplies to the English soldiers at Orléans three days later.

This defeat was very bad for French morale. The French leaders blamed each other. Charles, disgusted, left the field and refused to fight anymore. Again, the Dauphin Charles was advised to make peace. Some even suggested he give up his claim to the throne.

Offer to Surrender

In March, John of Dunois made an offer to Philip III of Burgundy. He offered to give Orléans to Burgundy. It would be a neutral territory held for his captive half-brother, the Duke of Orléans. A group of nobles and citizens from Orléans went to Philip. They wanted him to convince the English to lift the siege. This way, Orléans could surrender to Burgundy instead.

The deal would have allowed the English to pass through Orléans. They could then attack Bourges, the Dauphin's capital. This was the main reason for the siege. Burgundy quickly went to Paris in early April. He tried to persuade the English regent, John of Bedford, to accept the offer. But Bedford was sure Orléans was about to fall. He refused to give up his prize. Philip was disappointed. He pulled his Burgundian soldiers away from the English siege on April 17, 1429. This left the English with a very small army to continue the siege. This decision turned out to be a big mistake for the English.

Joan's Arrival at Orléans

On the very day of the Battle of the Herrings, a young French peasant girl, Joan of Arc, met with Robert de Baudricourt. He was a French captain. Joan tried to explain her mission to him. She believed God had told her to rescue the Dauphin Charles. She was to take him to his coronation in Reims. She had met Baudricourt twice before, but he had refused to help. This time, he agreed to take her to the Dauphin's court in Chinon. It is said that Joan told Baudricourt that the Dauphin's forces had suffered a big loss near Orléans that day. When news of the defeat at Rouvray reached Baudricourt, he believed Joan. Joan left for Chinon on February 23.

For years, there had been prophecies in France. They spoke of an armored maiden who would save France. Many of these prophecies said she would come from the area near Lorraine. Joan's birthplace, Domrémy, is in that region. So, when the people of Orléans heard about Joan, they had high hopes.

Joan arrived in Chinon on March 6, 1429. She met the Dauphin Charles on March 9. After a few days, she had a private meeting with him. The Dauphin was convinced of her "powers" or at least that she could be useful. But he insisted she first go to Poitiers. There, church leaders would examine her. The church said she was harmless. So, the Dauphin Charles finally accepted her help on March 22. She was given armor, a banner, a pageboy, and heralds.

Joan's first task was to join a convoy at Blois. This convoy, led by Marshal Jean de La Brosse, was bringing supplies to Orléans. From Blois, Joan sent messages to the English commanders. She called herself "the Maiden" (La Pucelle). She ordered them, in God's name, to "Begone, or I will make you go."

The supply convoy, with about 400–500 soldiers, left Blois on April 27 or 28. Joan wanted to approach Orléans from the north. This is where the English forces were. She wanted to fight them right away. But the commanders decided to take a longer route around the south. They reached the Loire River at Rully, east of the city. Orléans' commander, Jean de Dunois, came to meet them. Joan was angry about the deception. She ordered an immediate attack on St. Jean-le-Blanc, an English fort. But Dunois and the Marshals convinced her to let the city be resupplied first. The convoy approached the Port Saint-Loup. Boats from Orléans sailed to pick up the supplies, Joan, and 200 soldiers. A famous story says that the wind suddenly changed direction. This allowed the boats to sail back to Orléans easily in the dark. Joan of Arc entered Orléans in triumph on April 29, around 8:00 PM. The people were very happy. The rest of the convoy returned to Blois.

Lifting the Siege

Over the next few days, Joan toured the streets of Orléans. She gave food to the people and paid the soldiers. Joan of Arc also sent messages to the English forts, telling them to leave. The English commanders laughed at her. Some even threatened to kill her messengers.

The Journal du siege d'Orléans describes talks between Joan and Jean de Dunois. Dunois was the main leader of the city's defense.

Dunois believed the soldiers were too few for an attack. So, on May 1, he left the city to La Hire. He went to Blois to get more soldiers. During this time, Joan went outside the city walls. She personally looked at all the English forts. At one point, she spoke with the English commander, William Glasdale.

On May 3, Dunois's convoy of reinforcements left Blois for Orléans. Other groups of soldiers also set out from Montargis and Gien. Dunois's soldiers arrived on the north bank of the river on May 4. The English soldiers at St. Laurent saw them. But they did not attack because the French force was too strong. Joan rode out to meet them.

Attack on St. Loup

At noon on May 4, 1429, Dunois attacked the English fort of St. Loup. He was joined by soldiers from Montargis and Gien. This attack was meant to secure the entry of more supply convoys. Joan almost missed the attack because she was napping. But she quickly joined in. The English fort had 400 soldiers. The French had 1,500 attackers. The English commander, Lord John Talbot, tried to distract the French. He attacked from St. Pouair, north of Orléans. But a French group pushed him back. After a few hours, St. Loup fell. About 140 English soldiers were killed, and 40 were captured. Some English defenders were found in a nearby church. Joan asked for their lives to be spared. Hearing that St. Loup had fallen, Talbot stopped his attack in the north.

Attack on the Augustines

The next day, May 5, was Ascension Day. Joan wanted to attack the largest English fort, St. Laurent, to the west. But the French captains knew it was strong. They also knew their men needed rest. So, they convinced her to let them rest for the holiday. That night, a war council decided to clear the English forts on the south bank. This was where the English were weakest.

The attack began early on May 6. The people of Orléans were inspired by Joan of Arc. They formed their own groups of fighters. They showed up at the gates, which surprised the professional soldiers. But Joan convinced the professionals to let the citizens join. The French crossed the river in boats. They landed on the island of St. Aignan. Then they crossed to the south bank using a temporary bridge. Their plan was to cut off and take St. Jean-le-Blanc from the west. But the English commander, William Glasdale, understood their plan. He quickly destroyed the St. Jean-le-Blanc fort. He moved his soldiers to the central Boulevart-Tourelles-Augustines complex.

Before the French had fully landed, La Hire launched a quick attack on the Boulevart. This almost ended badly. The attackers were exposed to English fire from the Augustines. The attack stopped when there were shouts that English soldiers from St. Privé were coming to help Glasdale. Panic spread, and the French attackers retreated. They dragged Joan back with them. Glasdale's soldiers rushed out to chase them. But, according to legend, Joan turned around alone. She raised her holy banner and shouted "Au Nom De Dieu" ("In the name of God"). This reportedly made the English stop their chase and return to the Boulevart. The fleeing French soldiers turned around and rallied behind her.

French commanders then attacked the fortified monastery of "Les Augustins." It was finally captured just before nightfall.

With the Augustins in French hands, Glasdale's soldiers were trapped in the Tourelles complex. That same night, the remaining English soldiers at St. Privé left their fort. They went north of the river to join their comrades at St. Laurent. Glasdale was isolated. But he had a strong force of 700–800 English soldiers.

Attack on the Tourelles

Joan had been wounded in the foot during the attack on the Augustins. She was taken back to Orléans overnight to recover. So, she did not attend the evening war council. The next morning, May 7, she was asked to rest. But she refused. She joined the French camp on the south bank. The people of Orléans were very happy. The citizens gathered more fighters for her. They started repairing the bridge with beams. This would allow an attack on the fort from two sides. Cannons were placed on the island of Saint-Antoine.

Early in the morning, Joan was hit by an arrow while standing in the trench south of Les Tourelles. She was quickly taken away. Rumors of her death made the English defenders stronger and lowered French morale. But, according to witnesses, she returned later that evening. She told the soldiers that a final attack would capture the fort. Joan's chaplain later said that Joan knew she would be wounded. Other attacks on Les Tourelles during the day were pushed back. As evening approached, Jean de Dunois decided to leave the final attack for the next day. Joan heard this decision. She went to pray quietly. Then she returned to the area south of Les Tourelles. She told the soldiers that when her banner touched the fort wall, the place would be theirs. When a soldier shouted "It's touching! [the wall]", Joan replied "Tout est vostre – et y entrez!" ("All is yours, – go in!"). The French soldiers rushed in, climbing ladders into the fort.

The French won the day. They forced the English out of the boulevart and back into the Tourelles. But the drawbridge connecting them broke. Glasdale fell into the river and died. The French continued to storm the Tourelles itself, from both sides. The bridge was now repaired. The Tourelles, partly burning, was finally captured in the evening.

English losses were heavy. Including other actions that day, the English had nearly a thousand killed. 600 prisoners were taken. 200 French prisoners were found in the complex and set free.

End of the Siege

With the Tourelles complex captured, the English had lost the south bank of the Loire. There was little reason to continue the siege. Orléans could now easily receive supplies.

On the morning of May 8, the English soldiers on the north bank, led by the Earl of Suffolk and Lord John Talbot, destroyed their forts. They gathered in battle formation near St. Laurent. The French army under Dunois lined up opposite them. They stood facing each other for about an hour. Then the English left the field. They marched off to join other English units in Meung, Beaugency, and Jargeau. Some French commanders wanted to attack and destroy the English army right there. Joan of Arc reportedly forbade it, because it was Sunday.

What Happened Next

The English did not think they were completely defeated. Even though they had lost many soldiers at Orléans, the surrounding area was still in their hands. It was possible for the English to regroup and attack Orléans again soon. This time, they might have more success, as the bridge was now repaired. Suffolk's main goal on May 8 was to save what was left of the English forces.

The French commanders understood this. Joan less so. Leaving Orléans, she met the Dauphin Charles outside of Tours on May 13. She reported her victory. She immediately called for a march northeast towards Reims. But the French commanders knew they first had to clear the English out of their dangerous positions on the Loire River.

The Loire Campaign began a few weeks later. The French army grew with new volunteers and supplies. Even the exiled Arthur de Richemont was allowed to join. After a series of quick sieges and battles at Jargeau (June 12), Meung (June 15), and Beaugency (June 17), the Loire River was back in French hands. An English army rushing from Paris, led by John Talbot, was defeated at the Battle of Patay soon after (June 18). This was the first major victory for French forces in years. The English commanders, the Earl of Suffolk and Lord Talbot, were captured. Only then did the French feel safe enough to agree to Joan's request to march on Reims.

After some preparations, the march on Reims began from Gien on June 29. The Dauphin Charles followed Joan and the French army through dangerous Burgundian-held territory. Although Auxerre (July 1) closed its gates, Saint-Florentin (July 3) surrendered. So did Troyes (July 11) and Châlons-sur-Marne (July 15) after some fighting. They reached Reims the next day. The Dauphin Charles, with Joan by his side, was finally crowned King Charles VII of France on July 17, 1429.

Legacy

The city of Orléans celebrates the lifting of the siege every year. The festival includes both modern and medieval parts. A woman dressed as Joan of Arc rides a horse. On May 8, Orléans celebrates both the lifting of the siege and V-E Day (Victory in Europe, the end of World War II in Europe).

|

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Orleans para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Orleans para niños

- Medieval warfare

- The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World

- Jean Poton de Xaintrailles

- Joan of Arc bibliography

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |