Social anthropology facts for kids

Social anthropology is a field of study that looks at how people behave in different societies and cultures. It's a big part of anthropology in the United Kingdom and many parts of Europe. In the United States, it's often grouped with cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology.

Contents

What's the Difference: Social vs. Cultural Anthropology?

The term cultural anthropology usually describes studies that try to understand a whole culture. They look at how a culture affects individuals and aim to show a complete picture of a group's knowledge, customs, and ways of life.

Social anthropology, on the other hand, often focuses on specific parts of how a society is organized. This could include family life, how people make a living (economy), laws, politics, or religion. Social anthropologists look at how these systems work together to form a society. They see cultural things as important, but they focus more on the social structure.

Social anthropologists study many interesting topics. These include:

- Different customs and traditions.

- How societies organize their money and power.

- How laws work and how disputes are solved.

- How people buy and sell things.

- Family structures and relationships.

- Gender roles and how children are raised.

- Religious beliefs and practices.

Today, social anthropologists also study modern issues like globalism (how the world is connected), ethnic violence, gender studies, and how cultures change with new technologies like cyberspace. They can even help bring groups together when environmental concerns clash with new building projects. For example, some anthropologists studied Wall Street and helped explain the financial crisis of 2007–2010 in a different way than economists or politicians.

The differences between British, French, and American social and cultural anthropology are becoming smaller. This is because experts from these areas talk more and share ideas. Many universities now combine social and cultural anthropology into one department.

Social anthropology often uses qualitative research. This means they spend a lot of time (sometimes years!) living with and observing people. This is called fieldwork and involves participant observation. They usually don't rely as much on surveys or quick visits like economists or political scientists might.

How Social Anthropology Works

Social anthropology is different from subjects like economics or political science because it looks at the whole picture of a society. It also pays attention to how diverse societies and cultures are around the world. This helps us question our own ideas and assumptions.

It's also different from sociology because anthropologists often live with the people they study for a long time. They also learn the local language. This helps them understand small details that can explain bigger social ideas. Social anthropology goes beyond just social rules to look at culture, art, individual people, and how we think. Some social anthropologists also use numbers and statistics, especially when studying things like local economies, population changes, or health.

What Social Anthropologists Study

The topics social anthropologists focus on change as societies change and as new ideas appear. For example, musicology (the study of music) and medical anthropology (the study of health and illness in different cultures) are popular areas today.

Newer areas of study include:

- How our minds develop.

- How people understand new technologies.

- New types of families and social groups.

- The effects of the end of state socialism.

- The politics of new religious movements.

- How organizations are checked and held accountable.

Social anthropology has also learned from other fields like philosophy (thinking about right and wrong), the history of science, and linguistics (the study of language).

Being Fair and Careful

This field also involves thinking about what is right and wrong. Anthropologists have learned that they can sometimes change the very societies they are studying just by being there. This is like the "hawthorne effect", where people act differently when they know they are being watched.

A Look Back: History of Social Anthropology

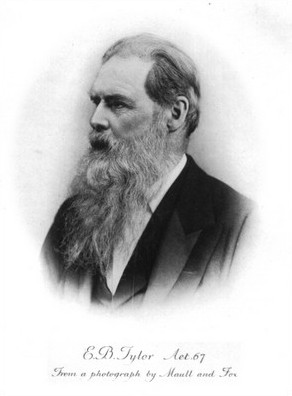

Social anthropology has its roots in many studies from the 1800s, like Classics (ancient Greek and Roman studies), ethnography (describing cultures), and sociology (the study of society). It really started to take shape in the late 1800s with people like Edward Burnett Tylor and James George Frazer. Around 1890–1920, it changed a lot. People started doing more original fieldwork, studying social behavior in natural settings for long periods, and using new ideas from French and German thinkers.

Bronisław Malinowski, a Polish anthropologist, was very important for British social anthropology. He believed in long-term fieldwork where anthropologists lived among local people and learned their language and daily customs. This idea was also supported by Franz Boas's idea of cultural relativism. This means that cultures are based on different ideas, so we should understand them by their own rules, not by judging them with our own.

Sadly, in the past, some museums and even zoos displayed people from other cultures. These were sometimes called "human zoos". For example, in 1906, a Congolese man named Ota Benga was put in a cage at the Bronx Zoo. This was wrong and based on racist ideas that tried to show some people as less developed than others. These exhibitions were attempts to prove ideas of scientific racism, which were very harmful. Even in 1931, a big exhibition in Paris showed people from New Caledonia in a "native village," and millions of people visited it.

Anthropology became more distinct from natural history by the end of the 1800s. By 1935, it was a recognized field of study. At that time, many believed that all societies went through the same steps of development, from simple to advanced. Non-European societies were sometimes seen as "living fossils" that could help understand Europe's past. People also discussed the idea of race to classify and rank human beings, which was a harmful idea.

Early Thinkers: Tylor and Frazer

Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) and James George Frazer (1854–1941) are seen as early pioneers of modern social anthropology in Great Britain. While Tylor did visit Mexico, both he and Frazer mostly learned about other cultures by reading many books. They read about ancient Greece and Rome, old European folk tales, and reports from missionaries and travelers.

Tylor believed that all humans develop in similar ways. He also thought that different groups could have similar cultural things in three ways: inventing them on their own, inheriting them from ancestors, or learning them from another group.

Tylor gave one of the first important definitions of culture. He said it was "that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by [humans] as [members] of society." However, he mostly focused on describing and mapping different parts of culture. He also believed in a Victorian idea of progress, meaning cultures always get better. Tylor also thought about where religious beliefs came from. He suggested that animism (believing in spirits in nature) was the earliest stage of religion.

Frazer, a Scottish scholar, also studied religion, mythology, and magic. In his famous book, The Golden Bough, he looked at similarities in religious beliefs and symbols around the world. Neither Tylor nor Frazer were very interested in doing fieldwork themselves. They also didn't focus on how different parts of a culture fit together.

Malinowski and the British Approach

Around the early 1900s, some anthropologists felt that just listing cultural items wasn't enough. They also thought that trying to guess past histories was too uncertain. A new way of thinking became popular among British anthropologists. They wanted to understand how societies worked now (called synchronic analysis), not just how they changed over time. They also emphasized long-term fieldwork, staying for one to several years.

In 1898, Cambridge University sent a team of experts to the Torres Strait Islands. This team included a doctor who was also an anthropologist, William Rivers, a language expert, a plant expert, and others. Their findings set new standards for describing cultures.

About 15 years later, a Polish anthropology student named Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) went to New Guinea for what he thought would be a short trip. But then World War I started, and he was stuck there for several years.

He used this time to do much more intense fieldwork than anyone before him. His famous book, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), introduced a new way of doing fieldwork. He said anthropologists should try to get "the native's point of view" by living with people and joining in their daily lives (this is participant observation). He also believed in a functionalist idea, which looked at how social groups and rules worked to meet people's needs.

From the 1920s to 1940s

Modern social anthropology in Britain began at the London School of Economics and Political Science after World War I. It was shaped by Malinowski's new fieldwork methods and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown's ideas about comparing societies. Radcliffe-Brown focused on how social structures worked together, similar to the ideas of French sociologist Émile Durkheim. Other important early thinkers included W. H. R. Rivers and E. B. Tylor.

A. R. Radcliffe-Brown also published an important book in 1922. He had done his first fieldwork in the Andaman Islands. After reading the work of French sociologists Émile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Radcliffe-Brown wrote about his research in a way that focused on the meaning and purpose of rituals and myths. He developed an idea called structural functionalism. This idea looked at how different parts of a society work to keep the social system balanced and harmonious. His ideas were different from Malinowski's functionalism and also different from later French structuralism, which looked at ideas and symbols in language.

Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown were very influential because they trained many students and built up university departments. Radcliffe-Brown, especially, spread his ideas about "Social Anthropology" by teaching at universities across the British Empire and Commonwealth. From the late 1930s to after the war, many important books were published that shaped British Social Anthropology (BSA). Famous studies include The Nuer by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard and The Dynamics of Clanship Among the Tallensi by Meyer Fortes.

After World War II

After World War II, social anthropology in Europe changed. It started to question the old ideas of structure-functionalism. It also took in ideas from Claude Lévi-Strauss's structuralism and from the followers of Max Gluckman. These new ideas led to studying conflict, change, cities, and social networks. Gluckman and his colleagues at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute and students at Manchester University (known as the Manchester School) brought in ideas from Marxism. They focused on conflicts and how they were solved, and how individuals used social structures.

In Britain, anthropology had a big impact. It helped people understand cultural relativism (that different cultures have different values) and that some "primitive" ways of life still exist in modern times. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, Edmund Leach and his students introduced French structuralism, following the style of Claude Lévi-Strauss.

In countries that were part of the British Commonwealth, social anthropology was often separate from physical anthropology (the study of human evolution and biology) and primatology (the study of primates). These might be in biology departments. Archaeology (the study of past human life through remains) might be linked to history departments. In other places, anthropologists also work with scholars of cultural studies, ethnic studies, folklore, and sociology. British anthropology has continued to focus on how societies are organized and how they manage their economies, rather than just on symbols or stories.

From the 1980s to Today

The European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) was started in 1989 by scholars from fourteen European countries. This group helps promote anthropology in Europe by holding conferences and publishing a journal. Social anthropology departments at different universities around the world now focus on many different parts of the field. The field has grown in ways that the first anthropologists never imagined, for example, in the study of structure and dynamics.

Important Social Anthropologists

- Andre Beteille

- Aleksandar Boskovic

- Edmund Snow Carpenter

- Mary Douglas

- Thomas Hylland Eriksen

- E. E. Evans-Pritchard

- Raymond Firth

- Rosemary Firth

- Meyer Fortes

- Ernest Gellner

- Stephen D. Glazier

- Jack Goody

- David Graeber

- Don Kalb

- Adam Kuper

- Edmund Leach

- Murray Leaf

- Claude Lévi-Strauss

- Alan Macfarlane

- Bronisław Malinowski

- Siegfried Frederick Nadel

- Susan Visvanathan

- A.H.J. Prins

- Alfred Radcliffe-Brown

- Audrey Richards

- Juan Mauricio Renold

- Victor Turner

- Marshall Sahlins

- Philippe Descola

- Marilyn Strathern

- Hebe Vessuri

- Douglas R. White

- Eric Wolf

- Robert Layton

- Judith MacDougall

- David MacDougall

See also

In Spanish: Antropología social para niños

In Spanish: Antropología social para niños

- Cultural anthropology

- Ethnology

- Ethnosemiotics

- List of important publications in anthropology

- Rajamandala

- Sociology

- Structuralism