Sydney punchbowls facts for kids

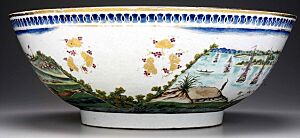

The Sydney punchbowls are two special bowls made in China a long time ago, between 1796 and 1820. They are unique because they are the only known Chinese porcelain bowls hand-painted with scenes of early Sydney, Australia, from the time when Lachlan Macquarie was governor.

These bowls were bought in a Chinese city called Canton (now Guangzhou) about 30 years after the First Fleet arrived in Port Jackson in 1788. They also show how Australia, China, and India traded with each other back then. Punchbowls were fancy items used for serving drinks at parties in the 1700s and 1800s. We don't know who first ordered these specific Sydney punchbowls or why they were made.

The two punchbowls are like a "harlequin pair" – similar but not exactly the same. They were given to different places: one to the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW) in 1926 and the other to the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) in 2006. The Library bowl is more famous. It was first known to be in England in the late 1840s. Some people think it was made for William Bligh, while others suggest Henry Colden Antill. The Museum bowl first appeared in England in 1932, and some believe it was made for Arthur Phillip. It was lost for a while until it showed up at the Newark Museum in the United States in 1988. Later, it was donated to the Maritime Museum.

The punchbowls are colorful, with gold decorations. They show wide views of Sydney in the early 1800s, along with traditional Chinese designs. Both bowls also feature a rare and lively scene of Aboriginal people. The Sydney scenes are very detailed and show many famous places around Sydney Cove at that time. The pictures on the bowls were probably copied from artworks by different artists who worked in Australia in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Contents

History of the Bowls

How They Came About

In the 1700s, hand-painted Chinese porcelain dinnerware became very popular in Europe and North America. Owning these items showed how rich and important you were. People ordered this porcelain through different trading companies, like the East India Companies, which had ships sailing to China.

The porcelain was decorated with a mix of Chinese patterns and Western designs chosen by the buyer. Chinese makers would send samples of decorations, and customers would provide drawings or sketches for their orders. These dinner sets were grouped by their main colors, like famille verte (green), noire (black), jaune (yellow), and rose (pink).

These sets included many dishes for a big dinner. For example, a 1766 order form from the Swedish East India Company showed that a "small service" had 224 pieces! But punchbowls were not part of these sets. They were ordered separately as special display pieces. People used them to serve hot or cold drinks at parties, clubs, or wealthy homes.

After the British settled Sydney Cove in 1788, much of the Chinese porcelain came to Australia through British traders in India. This trade was called the 'Country Trade'. Ships from India, often built there, brought supplies, including Chinese porcelain, to the early Australian colonies.

The two Sydney punchbowls are the only known examples of Chinese porcelain painted with Sydney scenes from the Macquarie era (1810–1821). They were bought in China between 1796 and 1820, about 30 years after the First Fleet arrived. By 1850, British-made pottery with printed Chinese designs had mostly replaced Chinese porcelain imports.

What They Were Used For

While people did drink punch from punchbowls, the Sydney Cove punchbowls were special and expensive. They likely had other uses too. Such punchbowls were owned by important people, like John Hosking, Sydney's first elected Mayor. They could also have been made as special gifts, like the 1812 Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania Union Lodge punchbowl.

It's also possible the Sydney punchbowls were used to promote the new settlement and encourage more people to move there. In 1820, a merchant named Alexander Riley wanted to promote the New South Wales colony. He thought a large painting (a panorama) of Sydney shown in London would make people interested in the colony. The punchbowls were a way to show off the new colony in a more glamorous way, rather than just a distant place for convicts.

Who Ordered Them?

The gold initials on the Library punchbowl might be the only clue about who first ordered these bowls. The initials are hard to read because some of the gold has worn off. Possible initials include HCA or HA. Many people have been suggested, including Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst and Thomas Brisbane, a Governor of New South Wales. But the most likely person is Henry Colden Antill (1779–1852).

Antill arrived in Sydney on January 1, 1810, and became a special assistant to Governor Macquarie. He retired from the army in 1821 and settled on land near Picton. When the State Library got its punchbowl in 1926, Antill's family didn't know anything about the bowl's history.

How They Were Found in the 1900s

The Library Punchbowl

The State Library's punchbowl became well-known earlier than the other one. It was given to the Library by William Augustus Little, an antiques dealer from Sydney, in November 1926. Newspapers reported this event. They said Little bought the bowl from a London bookseller and had it checked by experts from the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in February 1926. The V&A even wanted to keep the bowl! The articles also said the bowl had "paintings of Sydney in 1810, made for Major Antill."

Before Little bought it, the punchbowl belonged to Timothy Augustine Coghlan, who was a New South Wales Agent-General in London. He bought the bowl in 1923. After Coghlan's death in 1926, the bowl was with the bookseller. Coghlan had bought the bowl from a Miss Hall, who said her father got it in the late 1840s. Miss Hall believed the bowl was made for William Bligh, who was governor from 1806 to 1808. In 2002, the State Library made digital images of the punchbowl, and it was shown as one of 100 special library items in 2010.

The Museum Punchbowl

The second Sydney punchbowl had a much longer journey to its current home. It first appeared in May 1932 when Sir Robert Witt asked if a Sydney museum would want to buy it. The offer was passed to William Herbert Ifould, the head librarian in New South Wales. Ifould said the Library didn't need it because they already had a similar one. Sir Robert Witt replied that the owner had sold it to someone else. The bowl's location was unknown until 1988. Sir Robert had suggested this bowl was made for Arthur Phillip, the first Governor of New South Wales, but he didn't provide proof.

1988 was Australia's 200th anniversary of European settlement, so there was new interest in the "lost" second Sydney punchbowl. It was found in a catalog for an exhibition at the Newark Museum in the United States. The bowl was on loan from Peter Frelinghuysen Jr., a former US Congressman. A Sydney journalist, Terry Ingram, discovered it and wrote about it. It turned out that Frelinghuysen's parents had bought the bowl in the early 1930s.

This discovery caught the attention of Paul Hundley, a curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM). In May 2006, the ANMM announced it had bought the bowl, partly as a gift from Frelinghuysen. The bowl was valued at $A330,000 at the time. It has been on display at the Museum ever since.

Where the Bowls Were Made

The State Library's notes say that William Bowyer Honey, an expert from the Victoria and Albert Museum, checked the Library's punchbowl in 1926. He said it was made in China during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor (1796–1820).

From 1757, foreign trade in China was limited to Canton (Guangzhou). European and American traders had to pay for Chinese goods like tea, porcelain, and silk with silver. They were only allowed to stay in special trading houses called hongs in Canton. These Canton hongs are often shown on punchbowls, but pictures of other trading ports like Sydney and New York are very rare.

The Canton trading system lasted until China lost the First Opium War to the British in 1842. Very little Chinese export porcelain was made between 1839 and 1860 because of these wars. After the wars, Hong Kong became a major trading center, and many other "treaty ports" opened along China's coast. So, these punchbowls were made just before China's trading system changed. They were painted and glazed by Chinese artists in Canton. However, the plain bowls themselves were first made in Jingdezhen, a town about 800 kilometers (500 miles) from Canton, where pottery factories have been working for nearly 2,000 years.

How They Are Similar and Different

The punchbowls are a "harlequin pair" because they are similar but not exactly the same. Both are Chinese porcelain from Canton, made of hard porcelain with a clear glaze. They are painted with colorful famille rose enamel and gold. They are similar in size, each about 45 cm (18 in) wide, 17 cm (7 in) high, and weighing about 5.4 kg (12 lb).

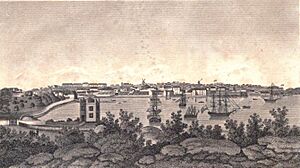

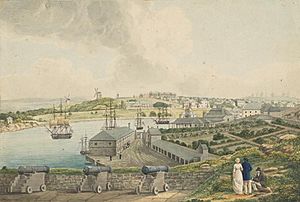

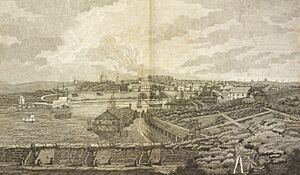

The pictures of the Aboriginal group in the center of both bowls are identical. However, the wide views of Sydney Cove on the outside are different. The Library bowl shows Sydney Cove from the eastern side, while the Museum bowl shows it from Dawes Point on the western side. This was a common way to show two views of the same place in art back then.

The Chinese artists probably copied the Sydney and Aboriginal scenes from pictures given by the customer. But the border designs were usually chosen by the artists themselves. Both bowls have similar traditional Chinese flower patterns on their inner borders, with flowers like chrysanthemums and peonies. However, their outer borders are quite different. The Library bowl has a more traditional Chinese design in red, pink, and gold. The Museum bowl has a border of looped circles on a blue background with gold edges.

Other differences include the Library bowl having large, gold initials on the outside and a single gold band on its base. The Museum bowl has no visible initials, but its base has "View of the Town of Sydney in New South Wales" written in black.

Where the Pictures Came From

Sydney Cove Scenes

We don't know the exact original pictures used for the Sydney Cove and Aboriginal group scenes. The colors on the bowls suggest that the artists copied from a watercolor painting or a hand-colored engraving, not just black and white images.

For the Library punchbowl, the Sydney Cove scene was probably copied from an engraving based on a lost drawing by artist John William Lewin, possibly from 1814. This engraving appeared in a book about New South Wales in 1820. Lewin was Australia's first professional artist and made many paintings for Governor Macquarie. He also had a close connection with Henry Colden Antill.

Unlike the Library punchbowl, the Sydney Cove picture on the Museum punchbowl is not known from any other existing artwork. So, the original drawing given to the Chinese artists is probably lost. A similar view from that time is a watercolor by artist Joseph Lycett. However, Lycett's version shows the Dawes Point Battery (fortifications) with guns in the front. The Museum punchbowl's view is older, showing a grassy slope with Aboriginal figures instead of the battery.

Aboriginal Group Scene

The Aboriginal group forms the center picture inside both bowls. Since the same image was used for both, it means the Chinese artists copied from the same drawing and likely finished them at the same time and place. The image shows four Aboriginal men with weapons, one woman with a baby on her shoulders, and another woman. This scene is thought to show a traditional ceremony.

Like the Museum bowl's Sydney Cove image, no exact original drawing used by the artists for the Aboriginal group is known today. The closest match is a drawing based on a lost sketch by Nicolas-Martin Petit, an artist on a French expedition to Australia from 1800 to 1803. The French expedition arrived at Port Jackson in April 1802. Petit's drawing was later copied for a book about a round-the-world voyage (1817–1820). The engraving was titled "Port Jackson, New Holland. Ceremony before a marriage among the natives." The Aboriginal people of Port Jackson were from the Eora group.

Sydney Cove Panoramas

The Library Punchbowl View

The scene on the Library punchbowl starts with a view of the eastern shore of Sydney Cove. In the front is a yellow, two-story sandstone house ①, built in 1812 for Governor Macquarie's boatman, Billy Blue. This small house, now the site of the Sydney Opera House, looks much bigger in the painting than it was in real life. To the left of the house is a sandy beach, where the Circular Quay ferry wharves are today. Facing the beach is First Government House ②, where the Museum of Sydney is now.

On the western shore is The Rocks district, where many convicts lived. It has two windmills on the ridge. The buildings were simple houses. Many convicts and Aboriginal people lived in this area in the 1790s. To the left of The Rocks is a long, low military barracks ③, built between 1792 and 1818. This is now Wynyard Park. It was from here that soldiers marched in 1808 to arrest Governor Bligh in an event known as the Rum Rebellion.

Further east is St. Philip's Church ④, Australia's first Christian church (Church of England). It was built in stone in 1810. The original church, made of mud and sticks, burned down in 1798. This was supposedly done by angry convicts after the governor ordered everyone to attend Sunday services.

Even further along the ridge to the east is Fort Phillip, flying the Union Jack flag. It was on Windmill Hill, now the site of the Sydney Observatory. This was the highest point above the colony, with great views of the harbor. On the waterfront below Fort Phillip is the yellow, four-story Commissariat Stores ⑤, built by convicts for Macquarie between 1810 and 1812. It was one of the largest buildings then and is now the site of the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. The buildings on the far right are the warehouse and home of merchant Robert Campbell ⑥, who became a big landowner. This area is now near the Sydney Harbour Bridge pylons. Three British sailing ships, flying either the Red Ensign or White Ensign, are anchored in the Cove, along with four sailboats and five canoes.

The Museum Punchbowl View

The Sydney Cove scene on the Museum punchbowl is from between 1812 and 1818. The view is from below Dawes Point, which is shown with its flagstaff before the fortifications were built (1818–1821) ⑦. Looking directly into Campbell's Cove, the main points are Robert Campbell's warehouse and the roof of his home ⑥. To the right of Campbell's Wharf are long stone walls marking property lines in The Rocks district ⑧.

First Government House can be seen in the distance at the head of Sydney Cove ②. Around the eastern shore, you can see a small picture of Billy Blue's 1812 house ①. The governor and other officials lived on the more organized eastern side of the Tank Stream, while convicts lived on the western side. The Tank Stream was the fresh water source for the colony until 1826. Further along is Bennelong Point, with no sign of Fort Macquarie (built from December 1817). Garden Island was the colony's first food source. The distant view of the eastern side of the Harbour goes almost as far as the Macquarie Lighthouse, Australia's first lighthouse, built between 1816 and 1818 on South Head. There are seven sailing ships flying the White Ensign of the British Royal Navy in the Harbour, along with three sailboats and two canoes.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |